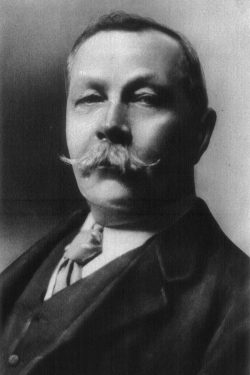

That Veteran by Arthur Conan Doyle

That Veteran

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

First published in All The Year Round, Sep 2, 1882

First book appearance in The Unknown Conan Doyle, 1929

That Veteran

“Served, sir? Yes, sir,” said my tattered vis-a-vis, drawing himself up and touching his apology for a hat. “Crimea and Mutiny, sir.”

“What arm?” I asked, lazily.

“Royal Horse Artillery. Thank you sir, I take it hot with sugar.”

It was pleasant to meet anyone who could talk English among those barren Welsh mountains, and pleasanter still to find one who had anything to talk about. I had been toiling along for the last ten miles, vowing in my heart never to take a solitary walking tour again, and, above all, never under any circumstances to cross the borders of the Principality. My opinions of the original Celt, his manners, customs, and above all his language, were very much too forcible to be expressed in decent society. The ruling passion of my life seemed to have become a deep and all-absorbing hatred towards Jones, Davis, Morris, and every other branch of the great Cymric trunk. Now, however, sitting at my eaze in the little inn at Langerod, with a tumbler of smoking punch at my elbow, and my pipe between my teeth, I was inclined to take a more rosy view of men and things. Perhaps it was thsa spirit of reconciliation which induced me to address the weather-beaten scarecrow in front of me, or perhaps it was that his resolute face and lean muscular figure attracted my curiosity.

“You don’t seem much the better for it,” I remarked.

“It’s this, sir, it’s this,” he answered, touching his glass with the spoon. “I’d have had my seven shillings a day, as retired sergeant-major, if it wasn’t for this. One after another I’ve forfeited them—my badges and my good service allowance and my pension, until they had nothing more to take rom me, and turned me adrift into tho world at forty-nine. I was wounded once in the trenches and once at Delhi, and this is what I got for it, just because I oouldn’t keep away from drink. You don’t happen to have a fill of ‘baccy about you? Thank you, sir; you are the first gentleman I have met this many a day.

“Sebastopol? Why, Lord bless you, I knows it as well as I know thia here village. You’ve read about it, may be, but I could make it clear to you in a brace of shakes. This here fender is the French attack, you see, and this poker is the Bussian lines. Here’s the Mamelon opposite the Frenoh, and the Redan opposite the English. This spittoon stands for the harbour of Balaclava. There’s the quarries midway between the Russians and us, and here’s Cathcart’s hill, and this is the twenty-four gun battery. That’s the one I served in towards the end of the war. You see it all now, don’t you, sir?”

“More or less,” I answered doubtfully.

“The enemy held those quarries at the commencement, and very strong they made them with trenches and rifle-pits all round. It was a terrible thorn in our side, for you couldn’t show your nose in our advanced works, but a bullet from the quarries would be through it. So at last the General, he would stand it no longer, so we dug a covering trenoh until we were within a hundred yards of them, and then waited for a dark night. We got our chance at last, and five hundred men were got together quietly under cover. When the word was given they made for the quarries as hard as they could run, jumped down, and began bayonetting every man they met. There was never a shot fired on our side, sir, but it was all done as quiet as may be. The Russians stood like men—they never failed to do that—and there was a rare bit of give-an’-take fightiug before we cleared them out. Up to the end they never turned, and our fellows had to pitchfork them out of the place like so many trusses of hay. That was the Thirtieth that was engaged that night. There was a young lieutenant in that corps, I disremember his name, but he was a terrible one for a fight. He wasn’t more’n nineteen, but was as tall as you, sir, and a deal stouter. They say that he never drew his sword during the whole war, but he used an ash stick, supple and strong, with a knob the size of a oocoa-nut at the end of it. It was a nasty weapon in hands like his. If a man came at him with a firelock, he could down him before the bayonet was near him, for he was long in the arm and active as well. I’ve heard from men in his company that he laid about him like a demon in the quarries that night, and crippled twenty, if he hit one.”

It seemed to me that the veteran was beginning to warm to his subject, partly, perhaps, from the effects of the brandy-and-water, and partly from having found a sympathetic listener. One or two leading questions were all that he would require. I refilled my pipe, settled myself down in my chair, put my weary feet upon the fender, and prepared to listen.

“They were splendid soldiers, the Russians, and no man that ever fought against them would deny it. It was queer what a fancy they had for the English, and we for them. Our fellows that were taken by them were uncommon well used, and when there was an armistice we could get on well together. All they wanted was dash. Where they were put they would stick, and they could shoot right well, but they didn’t seem to have it in them to make a rush, and that was where we had them. They could drive the French before them, though, when we were not by. I’ve seen them come out for a sortie, and kill them like flies. They were terribly bad soldiers— the worst I ever saw—all except the Zouaves, who were a different race to the rest. They were all great thieves, and rogues, too, and you were never safe if you were near them.”

“You don’t mean to say they would harm their own allies?” said I.

“They would that, sir, if there was anything to be got by it. Look at what happened to poor Bill Cameron, of our battery. He got a letter that his wife was ailing, and as he wasn’t vory strong himself, they gave him leave to go back to England. He drew his twenty-eight pound pay, and was to sail in a transport next day; but, as luck would have it, he goes over to the Frenoh oanteen that night, just to have a last wet, and he lets out there that he had the money about him. We found him next morning lying as dead as mutton between the lines, and so kicked and bruised that you oould hardly tell he was a human being. There was many an Englishman murdered that winter, sir, and many a Frenchman who had a good British pea-jacket to keop out the cold.

“I’ll tell you a atory about that, if I am not wearying you. Thank you, sir; I thought I’d just make sure. Well, four of our fellows—Sam Kelcey and myself,’ and Jack Burns and Prout—were over in the Frenoh lines on a bit of a spree. When we were coming back, this chap Prout suddenly gets an idea. He was an Irishman, and uncommon clever.

“‘See here, boys,’ says he; ‘if you can raise sixpence among you, I’ll put you in the way of making some money to-night, and a bit of fun into the bargain.’

” Well, we all agreed to this, and turned out our pockets, but we only had about fourpence altogether.

“‘Nivor mind,’ says Prout, ‘come on with me to the Frenoh canteen. All you’ve to do is to seem very drunk, and to keep saying ” Yes” to all I ask.'”

“All this time, sir, we hadn’t a ghost of an idea of what he was driving at, but we went stumbling and rolling into the canteen, among a crowd of loafing Frenchmen, and spent our coppers in a drain of liquor.

“‘Now,’ says Prout, loud out, so as everyone could hear, ‘are you ready to come back to camp?’

“‘Yes,’ says we.

“‘Have you got your thirty pounds safe in your pooket, Sam?’

“‘Yes,’ says Sam.

“‘And you, Bill,’ he says to me, ‘have you got your three months’ pay all right?’

“‘Yes,’ I answers.

“‘Well, come on then, and don’t tumble down more’n you can help,’ and with that we staggers out of the canteen and away off into the darknoss.

“By this time we had a pretty good suspicion of what he was after, but when we were well out of sight of evorybody he halted and explained to us.

“‘They’re bound to follow us after what we’ve said, and it’s queer if the four of us can’t manage to best them. They keep their money in little bags round their necks, and all you’ve got to do is to cut the string.’

“Wel, we stumbled on, still pretending to be very drunk, so as to have the advantage of a surprise, but never a soul did we see. At last we was within a stone’s-tkrow of our lines when we heard a whispering of ‘Anglais! Anglais!’ which is their jargon for ‘English,’ sir; and there, sure enough, was about a dozen men coming down against us in the moonlight. We stumbled along, pretending to be too drunk even to see them. Pretty soon they stopped, and one of them, a big stout man, sidles up to Sam Kelcey and says, ‘What time you call it?’ while the rest of them began to draw round us. Sam says nothing, but gives a terrible lurch, on which the Frenohie, thinking it all right, sprang at his throat.

“That was our signal for action, and in we went. Sam Kelcey was the strongest man in the battery and a terrible bruiser, and he caught this leader of theirs a clip under the jaw that sent him twice head over heels before he brought up against the wall, with the blood pouring from his mouth. The others made a run at un, but all they oould do was to kick and scream, while we kept knocking them down as quick as they could get to their feet. We had all their little bags, sir, and we left the lot of them stripped and senseless on the road. Five-and-thirty golden pieces in English money and French we counted out upon a knapsack when we got back to our quarters, besides boots and flannel shirts and other things that were handy. There was never another drunken man followed after that night’s work, for you see they never could be sure that it wasn’t a sham.”

The veteran paused for a moment to have a pull at his glass and listen to my murmur of appreciation. I was afraid that I had exhausted his story-telling capacities; but he rippled on again between the puffs of his pipe.

“Sam Kelcey—him that I spoke about—was a fine man, but his brother Joe was a finer, though a bit of a scamp in his day, like many a fine man is. When I was stationed at Gibraltar after the war Joe Kelcey was working at the fortifications as a convict, having been sent out of England for some little game or other. He was known to be a bold and resolute man, and the overseers kept a sharp look-out on him for fear he’d try to break away. One day he was working on the banks of the river and he seed an empty hamper come floating down—one that had come with wine, as like as not, for the officers’ mess. He gets hold of the hamper, and be knocks the bottom out, and stows it away among the rushes. Next morning we were having breakfast when in rushes one of the guard and cries, ‘Come on, boys; the five-of spades is up!’—the five-of-spades being a name they gave to the spotted signal they ran up when a convict had escaped. Out we all tumbled, and begin searching like hounds for a hare, because there was always a reward of two pounds for the finder. There wasn’t a drain or a hollow but was overhauled, and never a sign of Joe, till at last we gave him up in despair, and agreed that he must be at the bottom of the river.

“That afternoon I was on guard on the ramparts, and my eye chanced to light on an old hamper drifting about half a mile or so from the shore. I thought nothing of it at the time, but in a quarter of an hour I happened to oatch sight of the same object again. I stared at it in astonishment.

“‘Why,’ I said to the sentry on the wall, ‘that hamper’s going further away towards the Spanish shore. Blest if it isn’t moving against wind and tide and every law of Nature.’

“‘Nonsense!’ says he; ‘there’s alway a queer eddy in the straits.’

“Well, this didn’t satisfy me at all, so I goes up to Captain Morgan, of our battery, who was smoking his cigar, and I saluted and told him about the hamper. Off he goes, and is back in a minute with a spy-glass, and takes a peep through it.

“‘Bless my soul’! he cries, ‘why the hamper’s got arms sticking out of it! Ah, to be sure, it’s that rascal who esoaped this morning. Just run up the signal to the man-of-war.’

“We hoisted it, and in a few minutes two boats were in pursuit of the convict. Now if we had left well enough alone, Joe would have been caught sure enough, for he never knew he was found out, and was taking things leisurely, being an uncommon fine swimmer. But Captain Morgan says:

“‘Just wheel round this thirty-two pounder, and wo’ll drop a shot beside him to show him that we see him, and bring him to a halt.’

“We slewed the gun round, sir, and the captain looked along the sights and touched her off. A more wonderful shot you never saw, and the whole crowd that was on the ramparts gave a regular shout. It hit the top of the hamper and sent the whole thing flying in the air, so that we made sure that the man was killed. When the foam from the splash had cleared away, he was still there though, and striking out might and main for the Spanish coast. It was a close race between him and the boats, and the coxswain actually grabbed at him with a boat-hook as he clambered up on land, but there he was, and we could see him dancing about and chaffiog the men-o’-war’s men. There was a cheer, sir, when we saw him safe, for a plucky ohap like that deserves to be free, whatever he’s been and done. You look tired. You’ve had a long walk maybe. Perhaps you’d best have some rest.”

This remark, disinterested as it sounds, was given point to by the plaintive manner in which my companion gazed at the two empty glasses, as if it were evident that the proceedings of the evening had come to a close.

“It’s not often,” he murmured, “that a poor old soldier like me finds a gentleman as sociable-like and free as your honour.”

I need hardly say that after that I had no alternative but to ring the bell and order up a second edition of the brandy-and-water.

“You were talking about the Russians,” he continued, “and I told you they were fine soldiers. Some of their riflemen were as good shots as ever pulled a trigger. Excuse me, that glass is yours, sir, and the other is mine. Our sharpshooters used to arrange four sandbags, one on each side, one in front, and one crossways on the top, so as to cover them all round. Then, you see, they shot through the little slit between the bag in front and the one on the top; maybe not more than two inches across. You’ll hardly believe me, but I’ve seen at the distance of five hundred yards the bullets humming through the narrow slits as thick as bees. I’ve known as many as six men knocked over in half an hour in one of these sand-traps, as we used to call them; every one of them hit in the eye too, for that was the only part that showed.

“There is a story that reminds me of which might interest you. There was one Russian fellow that had a sand-pit all of his own, right in front of our trenches. I never saw anybody so persevering as that man was. Early in the morning he’d be popping away, and there he’d stay until nightfall, taking his food with him into the pit. He seemed to take a real pleasure in it, and as he was a very fine shot, and never let us get muoh of a ohance at him, he was not a popular character in the advanced trenches. Many a good fellow he sent to glory. It got such a nuisance that we dropped shells at him now and again, but he minded them no more than if they had been so many oranges.

“One day I was down in the trenches when Colonel Mancor, of the Forty-eighth, a splendid shot and a great man for sport, came along. A party with a sergeant were at work, and just as the colonel came up, one of them dropped with a ball through his head.

“‘Deuced good shot! Who fired that!’ says the colonel, putting up his eye-glass.

“‘Man in the rifle-pit to the left, sir,’ answers the sergeant.

“‘Never saw a neater shot,’ says the colonel. ‘He only showed for a moment, and wouldn’t have shown then, only that the edge of the trench is a bit worn away. Does he often shoot like that?’

“‘Terribly dangerous man,’ replies the sergeant; ‘kills more than all the guns in the Redan.’

“‘Now, major,’ says the colonel, turning to another officer as was with him, ‘what’s the odds against my picking him off?’

“‘In how long?’

“‘Within ten minutes.’

“‘Two to one, in ponies, I’ll give you,’ says the major.

“‘Say three, and it’s a bargain.’

“‘Three to one in ponies,’ answered the major, and the bet was made.

“He was a great man for measuring his powder, was the colonel, and alwaya emptied out a cartridge and then filled it up again according to his taste. He took about half his time getting the sergeant’s gun loaded to please him. At last he got it right, and the glass screwed well into his eye.

“‘Now, my lads,’ says he, ‘just push poor Smith here up over the trench. He’s dead enough, and another wound will make little difference to him.’

“The men began to hoist the body up, and the colonel stood, maybe 20 yards off, peering over the edge with eyes like a lynx. As soon as the top of Smith’s shako appeared, we saw the barrel of the gun come slowly out of the sand-pit, and when his poor dead face looks over the edge, whizz comes a bullet right through his forehead. The Russian he peeps out of the pit to see the effect of his shot, and he never looks at anything again until he sees the everlasting river. The colonel fired with a sort of a chuckle, and the rifleman sprang up in the air, and ran a matter of ten or twelve paces towards us, and then down on his faoe as dead ns a doornail. ‘Double or quits on the msn in the pit to the right,’ says the colonel, loading up his gun again, but I think the major had dropped money enough for one day over his shooting, for he wouldn’t hear of another try. By the way, it was handed over to Smith’s widow, for he was a free-handed gentleman, was the colonel, not unlike yourself, sir.

“That running of dead men is a queer thing. Perhaps your eddication may help you to understand it, but it beats me. I’ve seen it, though, many a time. I remember the doctor of our regiment saying it was commonor among men hit through the heart. What do you think about it, sir?”

“Your doctor was quite right,” I answered. “In several murder cases people who have been stabbed or shot through the heart have gone surprising distances afterwards. I never heard of such a case occurring in a battle, but I don’t see why it shouldn’t.”

“It happened once,” resumed my companion, “when Codrington’s division were going up the Alma, and were close on the great redoubt. To their surprise, a single Russian came running down tha hill against them, with his firelock in his hand. One or two fired at him, and seemed to miss him, for on he came till he got right up to the line, when a sergeant, as had seen a deal of service, gives a laugh, and throws his gun down in front of him. Down goes the Russian, and lies there stone dead. Had been shot through tha heart at the top of the hill, and was dead before ever he began that charge. At least, that’s what the sergeant said, and we all believied him.

“There was another queer incident of the same sort which happened later on in the war. Perhaps you may have heard of it, for it got into print at the time. One night a body, fearfully mangled and crushed, came crashing in among the tents of the light division. Nobody could make head or tail of it, until some deserters let it out long afterwards. It seems that they had one old-fashioned sort of gun with a big bore in a Russian battery. Now the night was cold, and the poor devil of a sentry thought he’d stow himself away where he’d never be seen, so he creeps inside the big gun, and goes to sleep there. In the middle of the night there was a sudden alarm of an attaok, and an artilleryman runs up to the gun and touches it off, and the sentry was flying through the air at twenty miles a minute. It didn’t much matter,” added the veteran philosophically, “for he was bound to be shot any way, for sleeping at his post, so it saved a deal of useless delay.”

“To a man who has seen so much of the world,” I remarked, “this humdrum life in a Welsh village must be very slow.”

“It is that, sir. It is that, sir. You’ve hit it there. Lord bless you, sir, if I had a gentleman like yourself to talk to every night I’d be a different man. I’ll tell you one reason now for my coming to this place,” here he leaned forward impressively. “I’ve got a wife in London, sir, but I came here to break myself of the drink. And I’m doing it slow, but sure. Why, three weeks ago, I oould never sleep unless I had my five glasses under my belt, and now I can manage it on three.”

“Waiter, another glass of brandy-and-water,” said I.

“Thank you, sir; thank you. As you said just now, I have had a stirring life, and this quiet business is too muoh for me. Did I ever tell you how I got my stripes? Why it was by hanging three men—three men with these very hands.”

“How was that?” I asked sleepily.

“It was like this, sir. We were in Corfu, three batteries of us, in ’50. Well, one of our officers—a lieutenant he was—went off into the mountains to shoot one day, and he never came back. His dog trotted into the messroom, however, and began to howl for all the world like a human being. A party was made up, and followed the dog, who led them right up among the hills to a place where there was a ditch. There, with a lot of ferns and suchlike heaped over him, the poor young fellow was lying with his throat cut from ear to ear. He was a great favourite in the regiment, and more particularly with the officer in command, and he swore that he’d have revenge. There was a deal of discontent among the Greeks on the island at tha time, and this had been encouraged by the priests—’pappas’ they call them. Well, when we got back to town the captain calls all these pappas before him, and there were three of them who could give no sort of account of themselves, but turned pale and stammered, and were terribly put out. A court martial was held, and the three of them were condemned to be hanged. Now came the difficulty, however, for it was well known that if anyone laid hands on a priest his life wasn’t worth an hour’s purchase. They are very strict about that are the Greeks, and uncommon handy with their knives. The captain called for a volunteer, and out I stepped, for I thought it was my duty, sir, seeing that I had been the dead man’s servant. Well, the troops formed square round the scaffold, and I hung them as high as Hamas. When the job was over, the captain says, ‘Now, my lad, I’ll save your life,’ and with that he forms the troops up into close order, puts me in the middle, and marches me down to the quay. There was a steamer there just casting off her warps for England, and I was shoved aboard, the crowd surging all round, and trying to get at me. You never heard such a howl as when they saw the ship steam out of the bay, and knew that I was gone. I have been a lonely man all my life, sir, and I may say that was the only time I have been honestly regretted when I left. We searched the ship when we got out to sea, and blessed if there weren’t three Greek stowaways aboard, each with his knife in his belt. We hove them over the side, and since I have never heard from them since I fear they may possibly have been drowned”; and the artilleryman grinned in high delight. “They made me a corporal for that job, sir.”

“By the way, what is your name?” I asked, getting more and more drowsy, partly from the heat of the fire, and partly from a curious feeling which was stealing over me and the like of which I had never experienced before.

“Sergeant Turnbull, air; Turnbull of B battery, Royal Horse Artillery. Major Campbell, who was over us in the Crimea, or Captain Onslow, or any of the old corps, would be glad to hear that you have seen me. You’ll not forget the name, will you, sir?”

I was too sleepy to answer.

“I could tell you a yarn about a Zouave that would amuse you. He was mortal drunk, and mistook the Russian lines for ours. They was having their supper in the Mamelon when he passes the sentry as cool as may be—prisoner—jumps—colonel —free—”

When I came to myself I found that I was lying in front of the smouldering fire, and that the candle was burning low. I was alone in the room. I staggered to my feet with a laugh, but my brain seemed to spin round, and I came down into my former position. Something was evidently amiss. I put my hand into my pooket to find out the time. It was empty. I gave a gasp of astonishment. My purse was gone too. I had been thoroughly rifled.

“Who’s in there?” cried a voice, and a small dapper man, rather past the prime of life, came into the room with a candle.

“Bless my soul, sir, my wifo told me a traveller had come, but I thought you were in bed long ago. I’m the landlord, but I’ve been away all day at Llanmorris fair.”

“I’ve been robbed,” said I.

“Robbed!” cried the landlord, nearly dropping the candle in his consternation.

“Watch, money—everything gone,” I said despondently. “What time is it?”

“Nearly one,” said he. “Are you sure there is no mistake?”

“No, there’s no mistake. I fell asleep about eleven, so he’s got two hours’ start.”

“There was a train left about an hour and a half ago. He’s clear away, whoever he is,” observed the landlord. “You seem weak, sir. Ah!” he added, sniffing at my glass; “laudanum, I see. You’ve been drugged, sir.”

“The villain! “I cried. “I know his name and history, that’s one blessing.”

“What was it? ” asked the landlord eagerly. “I’ll make every police station in the kingdom ring with it till I reach him. It is Sergeant Turnbull, formerly of B Battery.”

“Why, bless my soul!” oried my companion. “Why, I am Sergeant Turnbull of B Battery, with medals for the Crimea and Mutiny, sir.”

“Then who the deuce is he?”

A light eeomed to break upon the landlord.

“Was he a tall man with a scar on his forehead?” he asked.

“That’s him!” I cried.

“Then he’s the greatest villain unhung. Sergeant, indeed! Be never wore a uniform except a convict’s in his life. That’s Joe Kelcey.”

“And do you mean to say he never was in the Crimea?”

“Not he, sir. He’s cover been out of England, except once to Gibraltar, where he escaped very cleverly.”

“He told me—he told me,” I groaned; “and the officer with the stick, and the sporting colonel, and the running corpses, and the Greek priests—were they all lies?”

“All true as gospel, sir, but they happened to me, and not to him. He’s heard me tell the stories many a time in the bar, so he reeled them off to you, so as to get a chance of hocussing the liquor. He’s been reformed, and living here quiet enough, but being left alone with you, and seeing your watch, has been too much for him. Come up to bed, sir, and I’ll send round and let the police know all about it.”

* * * * *

And so, reader, I present you with a dtring of military anecdotes. I don’t know how you will value them. They cost me a good watoh and chain, and £14 7s 4d, and I thought them dear at the price.