The ‘Eroes of the Thames : by Bram Stoker

The ‘Eroes of the Thames

The Story of a Frustrated Advertisement

by

Bram Stoker

The ‘Eroes of the Thames

When Peter Jimpson, the professional swimmer, had won all the prizes to be had in the towns of Southern England, he thought that the time had come when he should attempt the possibilities of London. He was the more encouraged in the idea because his young son, whom he had brought up to his own calling, had developed quite a genius for his work. Not only could he swim so fast and stay so well that his father looked upon him as a future champion, but he had manifested a decided ability as an aquatic actor.

His tricks were always amusing, and, whether in the humours of a duck chase or exhibiting possibilities of the disasters which may happen to the imperfect swimmer, he showed undoubted power. Peter, therefore, determined to turn young Peter’s gift to advantage. He had long known that to win the attention of magnificent, rich, indifferent London, some sort of coup is necessary; there are so many workers of all kinds in the vast metropolis that merely to work is only to be one of many.

So all the early summer the two Peters rehearsed a little aquatic scena-that of a drowning boy rescued by a brave passing stranger. Many a time and oft, and always in secret-for the elder Peter impressed on his son the absolute necessity for silence-they went through every detail, till at last Peter junior could simulate the entire dangers and possibilities of an immersion.

He would fall into the water in the most natural way in the world; would struggle violently with his hands above water and his mouth open, after the manner of the ignorant; he would sink and rise again with strange portions of his anatomy appearing first above water, as though forced up by an irresistible current; he would gasp and choke and go down again; rise again with only his hands above water, and clutch at the empty air with writhing fingers in a manner which was positively heartrending to witness. Then the proud father knew that in his son were all the elements of success.

Wherefore they took their way to London. Having surveyed the various bridges they fixed on London Bridge as the scene of their exploit, and the hour when the afternoon throng was greatest as the time. They had several consultations, for it was necessary to be circumspect; the bridge was always well-furnished with police, and on two occasions they had noticed that different men had eyed them curiously, as though they were suspicious characters.

However, they fixed on every detail of their plan, leaving nothing to chance. As the construction of London Bridge does not allow of a small boy who is simply passing along to fall off by accident, and as to climb the parapet is at least a suspicious act, they arranged that Peter, having ascertained that neither passing barge nor steamer made a special source of danger, was to throw his son right over the parapet, and immediately jump after him.

They felt that in the excitement of the rescue-which they knew so well how to play-the crowd would instantly line the parapet, and would lose sight of the seemingly lethal act. They anticipated a rich harvest of praise, and possibly of a more tangible kind of reward; in any case, their fame as swimmers would be noised abroad.

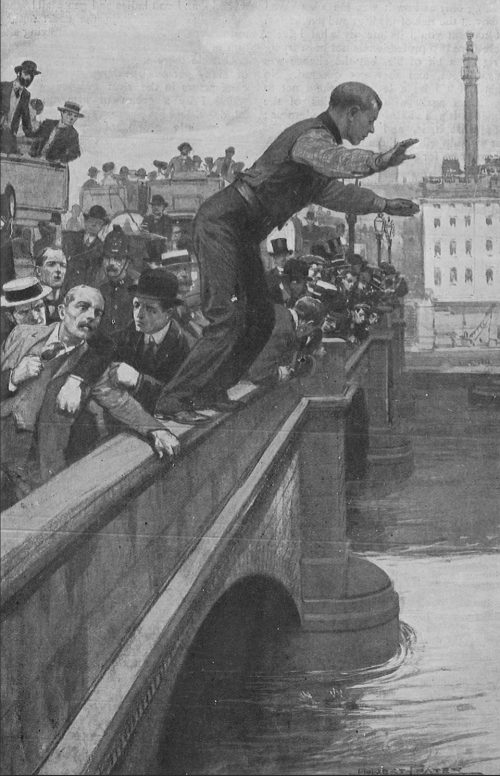

Next day at the appointed time, when London Bridge was almost a solid mass of vehicles, horsemen, and pedestrians, they made their enterprise. Having seen that no barge or steamer was close, they moved to the pathway over the very centre arch of the bridge on the down-river side as the current was running up.

There Peter, suddenly seizing the boy, hurled him with a mighty effort over the parapet into the water, and the instant after began to climb after him. But just as he was gaining a footing a man rushed forward and caught him by the ankles, and dragged him back upon the pavement. Peter turned on him furiously, and saw that his captor was one of the very men whom he had seen watching him on a previous occasion.

“Let me go!” he cried, “let me go! I must save my boy!” and he struggled frantically.

“A new way to save him, to throw him over the bridge!” said the man, who held him in a grip of iron.

“My boy! my boy! I must save my boy!” cried Peter appealingly to the crowd.

“Your boy will be saved if the bravest fellow in England can do it. Look there!” came the answer, and the crowd began to cheer; for just at the moment another man leapt upon the parapet, and, throwing off his coat, dived into the river. Some of the crowd helped to hold Peter, who struggled wildly, none the less that he had recognised in the man who jumped from the bridge another of the men whom he had seen watching him.

The tide was running so strongly up stream that young Peter was in a second or two after his immersion carried under the shadow of the arch, and close behind him his rescuer also disappeared from view. There was an instant rush across the bridge, and in a moment the up-river parapet was black with people, all looking eagerly for their coming through the arch.

The seconds seemed ages; but at length those exactly over it saw the body of the little boy drifting along just under the water, and turning round as it came. As soon as the bridge was cleared, and the sunlight reached the water above him, there was a violent struggle, a kicking about of the little chap’s arms and legs in seemingly a death-struggle. And then the horrified spectators saw two little hands rise above the water, clutch violently at the air, and sink again. Then the angle of refraction became too great, and even those on the centre arch could see no more.

There was a deep groan from the crowd; which, however, turned to a cheer as a man swimming overhand with a powerful stroke swept through the arch in the wake of the missing boy. A thousand hands pointed to where the child had gone down, and a thousand voices roared a thousand different directions. But the swimmer seemed to know instinctively the right spot, and making for it, turned head foremost and went down into the deep water to search for him.

There must have been some strange currents running round the piers of London Bridge that tide, for suddenly the crowd seemed to realise all at once that the boy’s body had risen out of the water not directly in the track of the stream, but at a spot some dozen or more yards on the Surrey side. In the moments that had elapsed the little chap had had time to draw his breath, and in the stillness around-for the roar of the traffic had ceased for the moment-the crowd hearth his faint cry:

“Oh, father! father!”

There was an instant shiver through the crowd, such as is seen when a sudden breeze sweeps over a cornfield, for instinctively everyone had turned his head backward to look at the guilty father. The fierce howl that swept from the mass of people showed that it was just as well that a strong force of police now surrounded the prisoner, or his life might have been in danger.

In the meantime, the man had risen from his dive and the boy had again sunk; again the crowd roared and pointed, and the man had with a few powerful strokes gained the place. This time, however, he did not dive, for he knew that he must be ready to seize the body when it rose again, for it would be the last chance.

The crowd and the man alike waited in fearful suspense. The swimmer was a keen-eyed, powerful fellow; he raised his head well above the water, and kept looking all around him. It was well that he did so, for by another effort of those strange currents round the piers the boy’s body rose down the river this time, having travelled against the current, and being still close to London Bridge, where the great crowd could plainly see.

The swimmer seemed to jump forward in the water, and with half-a-dozen mighty overhand strokes came close and seized the boy by the back of the neck, and raised his head out of the water. The boy could not see him from the position in which he was held, but he again shouted, “Father! father!” but this time in ringing, joyous tones, which reached the crowd from Surrey to Middlesex.

By this time boats were coming up and down the river to the rescue, and it appeared to be well that they were at hand, for it seemed to be no easy task to rescue a child. The man who had appeared to swim so powerfully when alone seemed, now that he was hampered with the boy, to be hardly able to support himself.

Boy and man struggled together in a little maelstrom of their own creation, and more than once went under water, leaving only a mass of froth to show where they went down. Once, though, after such a disappearance, the boy rose first, and appeared to be making frantic efforts to get away; but the instant after appeared the man, who, with seemingly renewed vigour, followed him up and again caught him by the nape of the neck, and then never let him go-over water or under it-till the two were taken into the police boat, the man gasping, and the child seemingly senseless.

Then a mighty roar arose from the watching crowd. Handkerchiefs and hats were waved, and the rescuer looked proud as he waved his hand in recognition, sitting in the stern of the boat, and holding on his knees the little chap, who had now opened his eyes, and only struggled faintly as though by instinct. Then the boat took its way to the river police-station, and the crowd went about its business, all except two sections, one of which followed the boy and his gallant rescuer, and the other the father, under arrest for attempted murder.

At the police-court the magistrate was sitting and when Peter Jimpson was brought into the station he was told with policeman pleasantry how nice it would be that he would not have long to wait for his committal. Somehow, he did not seem to see the joke-it is wonderful what a difference in point of view there is between the inside and the outside of the dock-especially in matters of humour.

However, he began to think, with the result that when he was brought before the magistrate he found himself prepared to make a clean breast of his ill-starred effort to achieve notoriety. A policeman who had been on duty on London Bridge had from a little distance seen him throw the boy into the water, and the man who had first laid hands on him, John Polter, testified to the same; the charge was therefore simple enough, and no time was lost.

When in the court the charge was entered upon, Peter Jimpson made his explanation, saying that all that had been done was with his son’s consent and connivance, simply in order to bring their names as swimmers before the public. To which the magistrate drily replied that such a course was apt to be attended with misapprehension, and was not devoid even of serious risk, as doubtless the grand jury would let him know later on.

Whilst the proceedings were at this stage a great cheering was heard outside, and very soon the rescued boy and his rescuer entered the court. Young Peter, with every appearance of regret, corroborated his father’s statement as to his having been a consenting party to his immersion; whereupon the rescuer indignantly said:

“And do you mean to say, you little wretch, that you tried to deceive the public by a base pretence of danger? Oh, boy! boy! I feel a certain love for you since your life is due to my own valour; but I trust that such an acted lie shall never again be due to you-even in part!”

The boy covered his eyes with his hands, and his voice was broken as he answered:

“Oh, your worship, I ain’t agoin’ on such a racket never no more. This brave, kind gentleman has taught me a lesson which I’ll never forget!” And he took the man’s big hand in his two small ones, and bent over it and kissed it, whilst there was scarcely a dry eye in the court, even the magistrate being visibly affected. Peter Jimpson was about to say something angrily, but the clerk of the court motioned him to be silent. Then the rescuer, who gave his name as Tom Bolter, spoke:

“May I ask your worship to dismiss the case. I wouldn’t go for to take the liberty of speaking only as how it was me what saved the boy at the risk of my life; and mayhap on that account you’ll let me say what I feels. These here two professionals has been trying to rig up a bit of biz, but the chance was against them, and they got queerer. No doubt but it’ll be a lesson to them not to play tricks again with the feelins of the public! It’s a harrowin’ up tenderness; that’s what it is, and I am sure that if your worship will let them off this time they will never go for to do it again. Isn’t that so, mateys?”

Both the Peters pronounced eager acquiescence; so after some deliberation the genial, bald-headed magistrate said:

“Peter Jimpson, and you, too, Peter Jimpson junior, I trust that the severe lesson which you have this day learnt may not be thrown away upon you. You must always remember that any form of fraud is obnoxious to the law; and this was distinctly a fraud on your part. Perhaps-indeed, I am satisfied, that you thought it an innocent proceeding enough; but let me tell you that there was manifest throughout the mens rea, which the law holds to be a necessary part of ill-doing-the intent to deceive. I am convinced that you, Peter Jimpson, fully intended to follow your son into the water, or otherwise I should have by this time committed you for trial on the serious charge of attempted murder, and for this reason I shall dismiss the charge; but I trust that as you lay your head on your pillow to-night you will breathe a warm and earnest prayer for that most gallant fellow, Thomas Bolter-that most excellent swimmer and master of the art of life-saving, to whom you owe so much!”

There was great applause in court, and a voice in the back of the crowd said, “Good old Bolter!” but the crier instantly called, “Silence in the court.”

Then Tom Bolter stood forward, and pulling his forelock respectfully, said:

“Your worship, what I done I done for the dear child’s good; but I thank your worship all the same for the kind and useful-and I hope I may say true-words which you have spoke of me. I’m only a unknown man in London as yet; but I am sure that before long you’ll hear of me in connection with saving life from drowning. When that time comes I ‘ope as you, your worship, and all these ‘ere ladies and gents as has done me so proud to-day concernin’ my gallant act’ll remember the name of Tom Bolter, and come and see me, even if you have to plank down your money for it. My service to you, your worship, and you ladies and gents all!” and Tom Bolter retired from the court amid a murmur of applause, the court emptying after him in a stream.

Outside there was soon a buzz and hum of many persons speaking, for each of the chief actors in the river episode was surrounded by a group of sympathisers or admirers.

One little group of sporting-looking young men stood apart listening to a betting man, whose calling was writ large on every square inch of his face and clothing.

“Well, blow me tight!” they heard him say, “if that ain’t the very cheekiest thing I ever see done; and, mind you, I’ve seen a few.”

“How do you mean, Sam?” came the chorus of questions.

” ‘Ow do I mean? Why, this, that the bally court and the ‘ole bloomin’ lot of yer is took in! They’ve been playin’ yer for suckers, the ‘ole bloomin’ lot of yer.”

“Who has, Sam?”

“Why, them two Northern chaps, Polter and Bolter, the champion swimmers of the Tyne. They’ve come to London to give an exhibition of life savin’ at the Hippodrome, an’ I’ve seen their printin’ lyin’ ready till their chance come. ‘Polter and Bolter, the ‘Eroes of the Thames,’ is wot they’re down as, and I’ve seen them the ‘ole of last week prowlin’ round the bridge lookin’ out for a chanst. My stars! but they done it fine; but the kiddy is the daisy of them all!”

In the meantime, in the group round the two Peters, the boy’s voice was heard above the babel:

“I tell you he’s the bravest chap and the finest swimmer in all the world! I ought to know since he took me out of the jaws of death! God bless him!”

Here Peter the elder whispered to him fiercely:

“Stow all that and keep yer ‘ead shut! Don’t crack him up; keep that for ourselves!” to which the dutiful boy answered aloud;

“No, father, I cannot hold my tongue! I must speak up for the brave and true!” Then he added in a whisper:

“Keep it up, dad! I’ve settled with them as we came up to the court. They’re goin’ to open in the Hippodrome and they’re to give you and me twenty quid a week to play up to them! You go on swimmin’, father, and be quicker in your jumps; but leave the business of the firm to me!”

The ‘Eroes of the Thames End