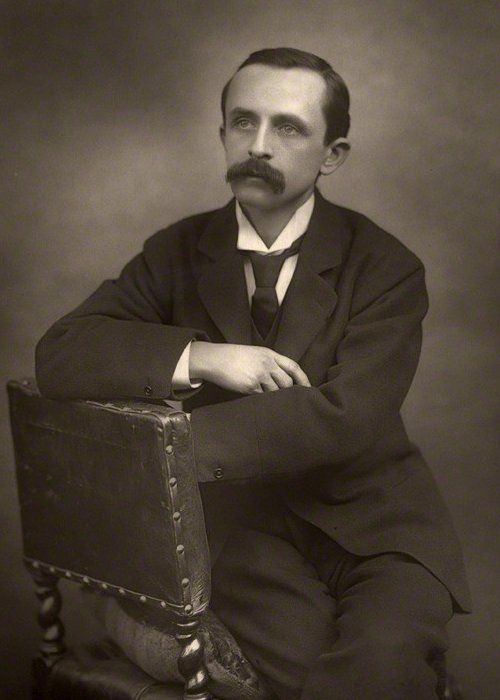

Every Man His own Doctor by James Matthew Barrie

From A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches by J. M. Barrie

Every Man His own Doctor

Statistics showing the number of persons who yearly meet their death in our great cities by the fall of telegraph wires are published from time to time. As our cities grow, and the need of telegraphic communication is more generally felt, this danger will become even more conspicuous. Persons who value their lives are earnestly advised not to walk under telegraph wires.

Is it generally realized that every day at least one fatal accident occurs in our streets? So many of these take place at crossings that we would strongly urge the public never to venture across a busy street until all the vehicles have passed.

We find prevalent among our readers an impression that country life is comparatively safe. This mistake has cost Great Britain many lives. The country is so full of hidden dangers that one may be said to risk his health every time he ventures into it.

We feel it our duty to remind holiday-makers that when in the country in the open air, they should never sit down. Many a man, aye, and woman too, has been done to death by neglecting this simple precaution. The recklessness of the public, indeed, in such matters is incomprehensible. The day is hot, they see an inviting grassy bank, and down they sit. Need we repeat that despite the sun (which is ever treacherous) they should continue walking at a smart pace? Yes, bitter experience has taught us that we must repeat such warnings.

When walking in the country holiday-makers should avoid over-heating themselves. Nothing is so conducive to disease. We have no hesitation in saying that nine-tenths of the colds that prove fatal are caught through neglect of this simple rule.

Beware of walking on grass. Though it may be dry to the touch, damp is ever present, and cold caught in this way is always difficult to cure.

Avoid high roads in the country. They are, for the most part, unsheltered, and on hot days the sun beats upon them unmercifully. The perspiration that ensues is the beginning of many a troublesome illness.

Country lanes are stuffy and unhealthy, owing to the sun not getting free ingress into them. They should, therefore, be avoided by all who value their health.

In a magazine we observe an article extolling the pleasures of walking in a wood. That walking in a wood may be pleasant we do not deny, but for our own part we avoid woods. More draughty places could not well be imagined and many a person who has walked in a wood has had cause to repent it for the rest of his life.

It is every doctor’s experience that there is a large public which breaks down in health simply because it does not take sufficient exercise in the open air. Once more we would remind our readers that every man, woman or child who does not spend at least two hours daily in the open air is slowly committing suicide.

How pitiful it is to hear a business man say, as business men so often say, “Really I cannot take a holiday this summer; my business ties me so to my desk, and, besides, I am feeling quite well. No, I shall send my wife and children to the seaside, and content myself with a Saturday-to-Monday now and again.” We solemnly warn all such foolish persons that they are digging their own graves. Change is absolutely essential to health.

Asked the other day why coughs were so prevalent in the autumn, we replied without hesitation, “Because during the past month or two so many persons have changed their beds.” City people rush to the seaside in their thousands, and here is the result. A change of beds is dangerous to all, but perhaps chiefly to persons of middle age. We have so often warned the public of this that we can only add now, “If they continue to disregard our warning, their blood be on their own heads.” This we say not in anger, but in sorrow.

A case has come to our knowledge of a penny causing death. It had passed through the hands of a person suffering from infectious fever into those of a child, who got it as change from a shop. The child took the fever and died in about a fortnight. We would not have mentioned this case had we not known it to be but an instance of what is happening daily. Infection is frequently spread by money, and we would strongly urge no one to take change (especially coppers), from another without seeing it first dipped in warm water. Who can tell where the penny he gets in change from the newspaper-boy has come from?

If ladies, who are ever purchasing new clothes, were aware that disease often lurks in these, they would be less anxious to enter dressmakers’ shops. The saleswoman who “fits” them may come daily from a home where her sister lies sick of a fever, or the dress may have been made in some East End den, where infection is rampant. Cases of the kind frequently come to our knowledge, and we would warn the public against this danger that is ever present among us.

Must we again enter a protest against insufficient clothing? We never take a walk along any of our fashionable thoroughfares without seeing scores of persons, especially ladies, insufficiently clad. The same spectacle, alas! may be witnessed in the East End, but for a different reason. Fashionable ladies have a horror of seeming stout, and to retain a slim appearance they will suffer agonies of cold. The world would be appalled if it knew how many of these women die before their fortieth year.

We dress far too heavily. The fact is, that we would be a much healthier people if we wore less clothing. Ladies especially wrap themselves up too much, with the result that their blood does not circulate freely. Coats, ulsters, and other wraps, cause far more colds than they prevent.

Why have our ladies not the smattering of scientific knowledge that would tell them to vary the thickness of their clothing with the weather? New garments, indeed, they do don for winter, but how many of them put on extra flannels?

We are far too frightened of the weather, treating it as our enemy when it is ready to be our friend. With the first appearance of frost we fly to extra flannel, and thus dangerously overheat ourselves.

Though there has been a great improvement in this matter in recent years, it would be idle to pretend that we are yet a cleanly nation. To speak bluntly, we do not change our undergarments with sufficient frequency. This may be owing to various reasons, but none of them is an excuse. Frequent change of underclothing is a necessity for the preservation of health, and woe to those who neglect this simple precaution.

Owing to the carelessness of servants and others it is not going too far to say that four times in five undergarments are put on in a state of semi-dampness. What a fearful danger is here. We do not hesitate to say that every time a person changes his linen he does it at his peril.

This is such an age of bustle that comparatively few persons take time to digest their food. They swallow it, and run. Yet they complain of not being in good health. The wonder rather is that they do not fall dead in the street, as, indeed, many of them do.

How often have doctors been called in to patients whom they find crouching by the fireside and complaining of indigestion! Too many medical men pamper such patients, though it is their plain duty to tell the truth. And what is the truth? Why, simply this, that after dinner the patient is in the habit of spending his evening in an arm-chair, when he ought to be out in the open air, walking off the effects of his heavy meal.

Those who work hard ought to eat plentifully, or they will find that they are burning the candle at both ends. Surely no science is required to prove this. Work is, so to speak, a furnace, and the brighter the fire the more coals it ought to be fed with, or it will go out. Yet we are a people who let our systems go down by disregarding this most elementary and obvious rule of health.

If doctors could afford to be outspoken, they would twenty times a day tell patients that they are simply suffering from over-eating themselves. Every foreigner who visits this country is struck by this propensity of ours to eat too much.

Very heart-breaking are the statistics now to hand from America about the increase in smoking. That this fatal habit is also growing in favor in this country every man who uses his eyes must see. What will be the end of it we shudder to think, but we warn those in high places that if tobacco smoking is not checked, it will sap the very vitals of this country. Why is it that nearly every young man one meets in the streets is haggard and pale? No one will deny that it is due to tobacco. As for the miserable wretch himself, his troubles will soon be over.

We have felt it our duty from time to time to protest against what is known as the anti-tobacco campaign. We are, we believe, under the mark in saying that nine doctors in every ten smoke, which is sufficient disproof of the absurd theory that the medical profession, as a whole, are against smoking. As a disinfectant, we are aware that tobacco has saved many lives. In these days of wear and tear, it is specially useful as a sedative; indeed, many times a day, as we pass pale young men in the streets, whose pallor is obviously due to over-excitement about their businesses, we have thought of stopping them, and ordering a pipe as the medicine they chiefly require.

Even were it not a destroyer of health, smoking could be condemned for the good and sufficient reason that it makes man selfish. It takes away from his interest in conversation, gives him a liking for solitude, and deprives the family circle of his presence.

Not only is smoking excellent for the health, but it makes the smoker a better man. It ties him down more to the domestic circle, and loosens his tongue. In short, it makes him less selfish.

No one will deny that smoking and drinking go together. The one provokes a taste for the other, and many a man who has died a drunkard had tobacco to thank for giving him the taste for drink.

Every one is aware that heavy smokers are seldom heavy drinkers. When asked, as we often are, for a cure for the drink madness, we have never any hesitation in advising the application of tobacco in larger quantities.

Finally, smoking stupefies the intellect.

In conclusion, we would remind our readers that our deepest thinkers have almost invariably been heavy smokers. Some of them have gone so far as to say that they owe their intellects to their pipes.

The clerical profession is so poorly paid that we would not advise any parent to send his son into it. Poverty means insufficiency in many ways, and that means physical disease.

Not only is the medical profession overstocked (like all the others), but medical work is terribly trying to the constitution. Doctors are a short-lived race.

The law is such a sedentary calling, that parents who care for their sons’ health should advise them against it.

Most literary people die of starvation.

Trades are very trying to the young; indeed, every one of them has its dangers. Painters die from blood poisoning, for instance, and masons from the inclemency of the weather. The commercial life on ‘Change is so exciting that for a man without a specially strong heart to venture into it is to court death.

There is, perhaps, no such enemy to health as want of occupation. We would entreat all young men, therefore, whether of private means or not, to attach themselves to some healthy calling.