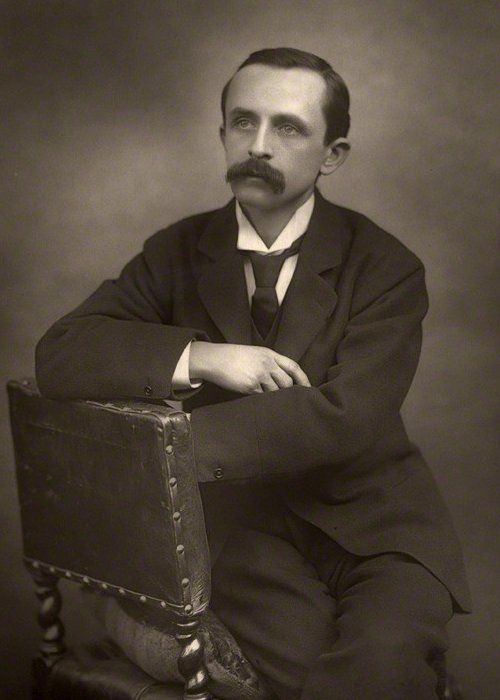

Life in a Country Manse — A Wedding in a Smiddy by James Matthew Barrie

From A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches by J. M. Barrie

Life in a Country Manse — A Wedding in a Smiddy

I promised to take the world at large into my confidence on the subject of our wedding at the smiddy. You in London, no doubt, dress more gorgeously for marriages than we do—though we can present a fine show of color—and you do not make your own wedding-cake, as Lizzie did. But what is your excitement to ours? I suppose you have many scores of marriages for our one, but you only know of those from the newspapers. “At so-and-so, by the Rev. Mr. Such-a-one, John to Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Thomas.” That is all you know of the couple who were married round the corner, and therefore, I say, a hundred such weddings are less eventful in your community than one wedding in ours.

Lizzie is off to Southampton with her husband. As the carriage drove off behind two horses that could with difficulty pull it through the snow, Janet suddenly appeared at my elbow and remarked:

“Well, well, she has him now, and may she have her joy of him.”

“Ah, Janet,” I said, “you see you were wrong. You said he would never come for her.”

“No, no,” answered Janet. “I just said Lizzie made too sure about him, seeing as he was at the other side of the world. These sailors are scarce to be trusted.”

“But you see this one has turned up a trump.”

“That remains to be seen. Anybody that’s single can marry a woman, but it’s no so easy to keep her comfortable.”

I suppose Janet is really glad that the sailor did turn up and claim Lizzie, but she is annoyed in a way too. The fact is that Janet was skeptical about the sailor. I never saw Janet reading anything but the Free Church Monthly, yet she must have obtained her wide knowledge of sailors from books. She considers them very bad characters, but is too shrewd to give her reasons.

“We all ken what sailors are,” is her dark way of denouncing those who go down to the sea in ships, and then she shakes her head and purses up her mouth as if she could tell things about sailors that would make our hair rise.

I think it was in Glasgow that Lizzie met the sailor—three years ago. She had gone there to be a servant, but the size of the place (according to her father) frightened her, and in a few months she was back at the clachan. We were all quite excited to see her again in the church, and the general impression was that Glasgow had “made her a deal more lady-like.” In Janet’s opinion she was just a little too lady-like to be natural.

In a week’s time there was a wild rumor through the glen that Lizzie was to be married.

“Not she,” said Janet, uneasily.

Soon, however, Janet had to admit that there was truth in the story, for “the way Lizzie wandered up the road looking for the post showed she had a man on her mind.”

Lizzie, I think, wanted to keep her wonderful secret to herself, but that could not be done.

“I canna sleep at nights for wondering who Lizzie is to get,” Janet admitted to me. So in order to preserve her health Janet studied the affair, reflected on the kind of people Lizzie was likely to meet in Glasgow, asked Lizzie to the manse to tea (with no result), and then asked Lizzie’s mother (victory). Lizzie was to be married to a sailor.

“I’m cheated,” said Janet, “if she ever sets eyes on him again. Oh, we all ken what sailors are.”

You must not think Janet too spiteful. Marriages were always too much for her, but after the wedding is over she becomes good-natured again. She is a strange mixture, and, I rather think, very romantic, despite her cynical talk.

Well, I confess now, that for a time I was somewhat afraid of Lizzie’s sailor myself. His letters became few in number, and often I saw Lizzie with red eyes after the post had passed. She had too much work to do to allow her to mope, but she became unhappy and showed a want of spirit that alarmed her father, who liked to shout at his relatives and have them shout back at him.

“I wish she had never set eyes on that sailor,” he said to me one day when Lizzie was troubling him.

“She could have had William Simpson,” her mother said to Janet.

“I question that,” said Janet, in repeating the remark to me.

But though all the clachan shook its head at the sailor, and repeated Janet’s aphorism about sailors as a class, Lizzie refused to believe her lover untrue.

“The only way to get her to flare up at me,” her father said, “is to say a word against her lad. She will not stand that.”

And, after all, we were wrong and Lizzie was right. In the beginning of the winter Janet walked into my study and parlor (she never knocks) and said:

“He’s come!”

“Who?” I asked.

“The sailor. Lizzie’s sailor. It’s a perfect disgrace.”

“Hoots, Janet, it’s the very reverse. I’m delighted; and so, I suppose, are you in your heart.”

“I’m not grudging her the man if she wants him,” said Janet, flinging up her head, “but the disgrace is in the public way he marched past me with his arm round her. It affronted me.”

Janet gave me the details. She had been to a farm for the milk and passed Lizzie, who had wandered out to meet the post as usual.

“I’ve no letter for ye, Lizzie,” the post said, and Lizzie sighed.

“No, my lass,” the post continued, “but I’ve something better.”

Lizzie was wondering what it could be, when a man jumped out from behind a hedge, at the sight of whom Lizzie screamed with joy. It was her sailor.

“I would never have let on I was so fond of him,” said Janet.

“But did he not seem fond of her?” I asked.

“That was the disgrace,” said Janet. “He marched off to her father’s house with his arm around her; yes, passed me and a wheen other folk, and looked as if he neither kent nor cared how public he was making himself. She did not care either.”

I addressed some remarks to Janet on the subject of meddling with other people’s affairs, pointing out that she was now half an hour late with my tea; but I, too, was interested to see the sailor. I shall never forget what a change had come over Lizzie when I saw her next. The life was back in her face, she bustled about the house as busy as a bee, and her walk was springy.

“This is him,” she said to me, and then the sailor came forward and grinned. He was usually grinning when I saw him, but he had an honest, open face, if a very youthful one.

The sailor stayed on at the clachan till the marriage, and continued to scandalize Janet by strutting “past the very manse gate” with his arm round the happy Lizzie.

“He has no notion of the solemnity of marriage,” Janet informed me, “or he would look less jolly. I would not like a man that joked about his marriage.”

The sailor undoubtedly did joke. He seemed to look on the coming event as the most comical affair in the world’s history, and when he spoke of it he slapped his knees and roared. But there was daily fresh evidence that he was devoted to Lizzie.

The wedding took place in the smiddy, because it is a big place, and all the glen was invited. Lizzie would have had the company comparatively select, but the sailor asked every one to come whom he fell in with, and he had few refusals. He was wonderfully “flush” of money, too, and had not Lizzie taken control of it, would have given it all away before the marriage took place.

“It’s a mercy Lizzie kens the worth of a bawbee,” her mother said, “for he would scatter his siller among the very bairns as if it was corn and he was feeding hens.”

All the chairs in the five houses were not sufficient to seat the guests, but the smith is a handy man, and he made forms by crossing planks on tubs. The smiddy was an amazing sight, lit up with two big lamps, and the bride, let me inform those who tend to scoff, was dressed in white. As for the sailor, we have perhaps never had so showily dressed a gentleman in our parts. For this occasion he discarded his seafaring “rig out” (as he called it), and appeared resplendent in a black frock coat (tight at the neck), a light blue waistcoat (richly ornamented), and gray trousers with a green stripe. His boots were new and so genteel that as the evening wore on he had to kick them off and dance in his stocking soles.

Janet tells me that Lizzie had gone through the ceremony in private with her sailor a number of times, so that he might make no mistake. The smith, asked to take my place at these rehearsals, declined on the ground that he forgot how the knot was tied: but his wife had a better memory, and I understand that she even mimicked me—for which I must take her to task one of these days.

However, despite all these precautions, the sailor was a little demonstrative during the ceremony, and slipped his arm around the bride “to steady her.” Janet wonders that Lizzie did not fling his arm from her, but Lizzie was too nervous now to know what her swain was about.

Then came the supper and the songs and the speeches. The tourists who picture us shivering, silent and depressed all through the winter should have been in the smiddy that night.

I proposed the health of the young couple, and when I called Lizzie by her new name, “Mrs. Fairweather,” the sailor flung back his head and roared with glee till he choked, and Lizzie’s first duty as a wife was to hit him hard between the shoulder blades. When he was sufficiently composed to reply, he rose to his feet and grinned round the room.

“Mrs. Fairweather,” he cried in an ecstacy of delight, and again choked.

The smith induced him to make another attempt, and this time he got as far as “Ladies and gentlemen, me and my wife——” when the speech ended prematurely in resounding chuckles. The last we saw of him, when the carriage drove away, he was still grinning; but that, as he explained, was because “he had got Lizzie at last.” “You’ll be a good husband to her, I hope,” I said.

“Will I not,” he cried, and his arm went round his wife again.