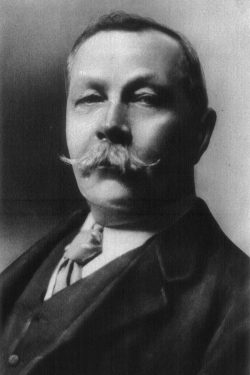

The Tragedians by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Tragedians

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Bow Bells, 20 August 1884.

The Tragedians Contents

The Tragedians I

The Tragedians II

The Tragedians III

The Tragedians IV

The Tragedians I

Night had fallen on the busy world of Paris, and its gay population had poured out on to the Boulevards; soldier and civilian, artistocrat and workman, struggled for a footing upon the pavement, while in the roadway the Communistic donkey of the costermonger jostled up against the Conservative thoroughbreds of the Countess de Sang-pur. Here and there a café, with its numerous little tables, each with its progeny of chairs, cast a yellow glare in front of it, through which the great multitude seemed to ebb and flow.

Let us leave the noise and bustle of the Boulevard des Italiens behind us, and turn to the right, along the Rue D’Egypte. At the bottom of this there lies a labyrinth of dingy little quiet streets, and the dingiest and quietest of them all is the Rue Bertrand.

In England, we should call it shabby-genteel. The houses are two-storied semi-detached villas. There is a mournful and broken-down look about them, as if they had seen better days, and were still endeavouring to screen their venerable tiles and crumbling mortar behind a coquettish railing and jaunty Venetian blinds.

The street is always quiet, but it is even quieter than usual to-night; indeed, it would be entirely deserted but for a single figure which paces backwards and forwards over the ill-laid pavement. The man—for a man it is—must be waiting or watching for someone, as the Rue Bertrand is the last place which the romantic dreamer would select for his solitary reverie. He is here with a purpose, no doubt, and what that purpose may be is no business either of ours or of the gendarme who comes clanking noisily round the corner.

There is a house just opposite the spot where the watcher has stationed himself, which exhibits not only signs of vitality, but even some appearance of mirth. The contrast, perhaps, has caused him to stop and gaze at it. It is neater and more modern-looking than its companions. The garden is well laid out, and between the bars of the green persiennes the warm light glows out into the street. It has a cheery, English look about it, which marks it out among the fossils which surround it.

If the outside gives this impression, it is confirmed by the appearance of the snug room within. A large fire is crackling and sparkling merrily, as if in playful defiance of the stolid lamp upon the table. There are two people seated in front of the blaze, both of the gentler sex, and it would take no very profound student of humanity to pronounce at a glance that they were mother and daughter.

In both there is the same sweet expression and the same graceful figure, though the delicate outlines of the younger woman are exaggerated in her plump little mother, and the hair which comes from under the matronly cap is streaked with traces of grey.

Mrs. Latour has had an anxious time since her husband, the Colonel, died, but has battled through it all with the uncomplaining patience of her race. Her second son, Jack, at a university in England, has been a grief to her, for Jack is sowing his wild oats, and vague reports of the process are wafted across the Channel, and startle the quiet household in the Rue Bertrand. There is Henry, too, with his great talent for tragedy, and no engagement for more than six months. It is no wonder that the bustling, kind-hearted little woman is sad at times, and that her cheery laugh is heard less frequently than of old. The sum which the Colonel had left behind him is not a large one; were it not for the supervision exercised by Rose it would hardly have met their necessary expenses.

This young lady would certainly never be expected to have the household virtues, if it be a fact that ornament and utility are seldom united in her sex. It is true that she was no regal beauty; her features had not even the merit of regularity; yet the graceful girl, with her laughing eyes and winning smiles, would be a dangerous rival to the stateliest of her sex. Unconsciousness of beauty is the strongest adjunct which beauty can have, and Rose Latour possessed it in an eminent degree. You could see it in every natural movement of her lithe form, and in the steady gaze of her hazel eyes. No wonder that even in the venerable Rue Bertrand, which should have been above such follies, there was a parting of window blinds when the dainty little figure went tripping down it, and that the blasé Parisian lounger, glancing at her face, sauntered on with the conviction that there was something higher in womanhood than he had met with in his varied experiences of the “Mubille” and the Cafés Chantants.

“Remember this, Rose,” the old lady was saying, emphasising every second or third word with an energetic little nod of the head, which gave her a strong resemblance to a plump and benevolent sparrow, “you are a Morton, and nothing but a Morton. You haven’t one drop of French blood in you, my dear!”

“But papa was a Frenchman, wasn’t he?” objected Rose.

“Yes, my dear; but you are a pure Morton. Your father was a dear good man, though he was a Frenchman, and only stood five feet four; but my children are all Scotch. My father was six feet two, and so would my brother have been only that the nurse used to read as she rolled him in the perambulator, and rested her book upon his head, so that he was compressed until he looked almost square, poor boy, but he had the makings of a fine man. You see, both Henry and Jack are tall men, so it is ridiculous to call them anything but Morton, and you are their sister. No, no, Rose; you haven’t one drop of your father’s blood in you!”

With which physiological deduction the good old lady dropped twenty stitches of her knitting and her ball of worsted, which rolled under the sideboard, with the strange instinct which all things dropped possess, and was only dislodged by Rose after ten minutes’ poking in the dark with fire-irons.

This little interruption seemed to change the current of Mrs. Latour’s ideas.

“Henry is later than usual to-night,” she remarked.

“Yes; he was going to the Theatre National to apply for an engagement, you know. I do hope he won’t be disappointed.”

“I’m sure I can’t conceive why they should ever refuse such a handsome young fellow,” said the fond mother. “I think, even if he could not act at all, they would fill the house with people who wanted to look at him.”

“I wish I were a man, mamma,” said Rose, pursing her lips to express her idea of masculine inflexibility.

“Why, what would you do, child?”

“What wouldn’t I do? I’d write books, and lecture, and fight, and all sorts of things.”

At which summary of manly accomplishments Mrs. Latour laughed, and Rose’s firmness melted away into a bright smile at her mother’s mirth.

“Papa was a soldier,” she said.

“Ah, my dear, there is no such thing as fighting now-a-days. Why, I remember, when I was a girl in London, how twenty and thirty thousand people used to be killed in a day. That was when young Sir Arthur Wellesley went out to the Peninsula. There was Mrs. McWhirter, next door to us—her son was wounded, poor fellow! It was a harrowing story. He was creeping through a hole in a wall, when a nasty man came up, and ran something into him.”

“How very sad!” said Rose, trying to suppress a smile.

“Yes; and I heard young McWhirter say, with his own lips, that he had never seen the man before in his life, and he added that he never wished to see him again. It was at Baggage-horse.”

“Badajos, ‘ma.”

“I said so, dear. The occurrence dispirited young McWhirter very much, and, indeed, threw a gloom over the whole family for the time. But England has changed very much since then in every way. Why, the very language seems to me to be altering in a marvellous manner. I doubt if I could make myself understood if I went back. There is Jack, at Edinburgh—he uses refinements of speech which you and I, Rose, have no idea of. We can’t keep up to the day when we are living in a foreign country.”

“Jack does use some queer words,” said Rose.

“I had a letter from him to-night,” continued the little old woman, diving first into her pocket, and then into her reticule. “Dear me! Oh, yes, here it is! I really can’t understand one word of it, my dear, except that the poor lad seems to have met with some sort of an accident or misfortune.”

“Acident, ‘ma?”

“Well, something unpleasant, at any rate. He does not enter into any particulars. Just listen, Rose, for it is very short. Perhaps you will be able to make out what it means; but I confess it has puzzled me completely. Where are my spectacles? It begins, ‘Dearest mother,—that is intelligible enough, and very gratifying, too, as far as it goes—’I have dropped a pony over the Cambridgeshire.’ What do you suppose your brother meant by that, dear?”

“I’m sure I don’t know, mamma,” said the young lady, after pondering over the mysterious sentence.

“You know he could not really have dropped a pony over anything. It would have been too heavy for him, though he is a strong lad. His poor dear father always used to say that he would be sure to have a very fine muscle; but that would be too much. It must be his way of saying that a pony dropped him over something, and no doubt he means that the accident occurred in Cambridgeshire.”

“Very likely, mamma.”

“Well, now, listen to this. ‘It was a case of scratching, so I was done for without a chance.’ Think of that, Rose! Something has been scratching the poor, dear boy, or else he has been scratching something; I’m sure I don’t know which. I shouldn’t think the pony can have scratched him, for they have hoofs, you know.”

“I don’t think it could have been the pony,” laughed Rose.

“It is all very mysterious. The next sentence is a little plainer. He says, ‘If you have any of the ready, send it.’ I know what he means by that, but it is the only intelligible thing in the letter. He wishes to pay his doctor’s fees, no doubt, poor boy! He adds in a postcript that he may run over very soon, so he cannot be much the worse.”

“Well, that’s consoling,” said Rose. “I hope he will come soon, and explain what it is all about.”

“We’d better lay the table for supper,” said the old lady. “Henry must come soon.”

“Never mind ringing for Marie,” said the daughter. “I am what Jack would call ‘no end of a dab’ at laying a table.”

The mother laughed as she watched her darling flitting about the room, and coming to endless grief over the disposition of her knives and forks.

“You have given the carver four knives,” she said, “while his right-hand neighbour has nothing but the steel to eat with. Listen, Rose; isn’t that your brother’s step?”

“There are two people.”

“One of them is he, I fancy.”

“So it is!” cried Rose, as the key was turned in the latch, and a masculine voice was heard in the hall. “How did you get on, Harry? Did you get it?”

And she took a spring into the passage, and threw her arms round her brother.

“Wait a bit, Rosey! Let me get my coat off before you begin to throttle me! It’s all right this time, and I have got an engagement at the ‘National.'”

“Didn’t I tell you, Rose?” said the mother.

“Come in, do, and let us know all about it!” pleaded Rose. “We are dying to know!”

“I mustn’t forget my politeness, though,” said Henry. “Let me introduce Mr. Barker, an Englishman, and a friend of Jack’s.”

A tall, dark young man, with a serious face, who was standing in the background, stepped forward, and made his bow.

(I may remark, in parenthesis, before proceeding further, that I myself was that Mr. Barker, and that what follows in this startling narrative is therefore written from my own personal observation.)

We went into the snug little drawing-room, and drew up to the cheery fire.

Rose sat upon her brother’s knee, while Mrs. Latour dropped her knitting, and put her hand into that of her son.

I leaned back in the shadow, at the other side of the hearth; while the gleam of the light played upon the golden tresses of the girl and the dark, stern profile of her brother.

“Well,” said Henry, “to begin at the beginning, I went to a café after I set out, and it was there that I had the good fortune to come across Mr. Barker, whose name I know very well from Jack.”

“We all seem to know you very well,” said the mother.

I smiled and bowed.

It was pleasant to be in this miniature England in the heart of France.

“We went together to the National,” continued Henry, “firmly believing I hadn’t the ghost of a chance, for Lablas, the great tragedian, has much influence there, and he always does his best to harm and thwart me, though I never gave him cause of offence that I know of.”

“Nasty thing!” said Rose.

“My dear, you really musn’t!”

“Well, you know he is, ‘ma. But go on, do!”

“I didn’t see Lablas there, but I managed to get hold of the manager, old Monsieur Lambertin. He jumped at the proposal. He had the goodness to say that he had seen me act at Rouen once, and had been much struck.”

“I should think so!” said the old lady.

“He then said that they were just looking out for a man to play an important rôle—that of Laertes, in a new translation of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet.’ It is to come out on Monday night, so that I have only two days to learn it in. It seems that another man, Monnier by name, was to have played it, but he has broken his leg in a carriage accident. You have no idea how cordial old Lambertin was!”

“Dear old man!” said Rose.

“But come, you must be hungry, Barker, and the supper is on the table. Pull up your chairs, and just have some water boiling afterwards, Rose.”

And so, with jest and laughter, we sat down to our little supper, and the evening passed away like a happy dream.

Looking back through the long vista of years, I seem to be able to recall the scene; the laughing, blushing girl, as she burned her fingers and spilt the water in her attempts at making punch; the purring little bright-eyed mother; the manly young fellow, with his honest laugh!

Who could have guessed the tragedy which was hanging over them? Who, except that dark figure that was then still standing in the Rue Bertrand, and whose shadow stretched across to darken the doorstep of number twenty-two?