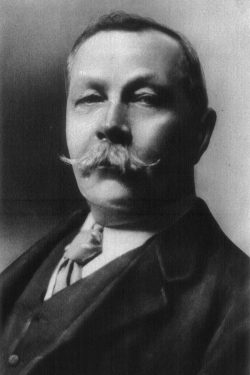

The Confession by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Confession

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Star, 17 January 1898.

The Confession

The Convent of the Third Order of Dominican Nuns—a large whitewashed building with little deep-set windows—stands at the corner of the Rua de St. Pedro in Lisbon. Inside the high wooden porch there is a life-size wooden statue of Saint Dominic, founder of the order, and the stranger is surprised to observe the curious scraps which are scattered over the pedestal. These singular votive offerings vary from week to week. For the most part they consist of cups of wine, splinters of firewood, crumbs of cheese, and berries of coffee, but occasionally a broken tin saucepan or a cracked plate is to be found among them. With simple faith the sisters, when their household stores run low, lay a piece of whatever it is they lack in front of their saint, as a reminder to him that they look to him for help; and sure enough upon the next day there arrives the wood, the wine, the new saucepan, or whatever else it is that they need. Whether this is due to a miracle, or to the help of the pious laity outside, may be a question to others, but it is none to the simple-minded Sisters of Saint Dominic. To them their whole existence is one continued miracle, and they point to the shelves of their own larder as a final refutation of every heretical doubt.

And had they been asked, these gentle fanatics, why their order above all others should be chosen for this constant supernatural care, they would have answered that it was a heavenly recognition of the sanctity of their Mother Superior. For twenty years Sister Monica had worked among those fallen classes which it is the special mission of the Dominican nuns to rescue. There was not an alley in Lisbon which had not been brightened by the flutter of her long white gown. And still as lady abbess she went on working and praying, with a tireless energy which put the young novices to shame. No one could compute how many there were who had been drawn from a life of sin through her exertions. For she had, above all things, the power of showing sympathy and of drawing the confidence of those who had suffered. They said that it was a sign that she had suffered herself; but none knew her early history, for she had come from the mountains of the north, and she spoke seldom and briefly of her own life. Her wax-like face was cold and serene, but there came a look sometimes into her large dark eyes which made the wretched and the poor feel that there was no depth of sorrow where the Abbess Monica had not been before them.

In the placid life of the convent, there is one annual event which is preceded by six months of expectation and followed by six of reminiscence. It is the yearly mission or “retreat,” when some reverend preacher comes among them, and, through a week of prayer and exhortation, stimulates these pious souls to a finer shade of spirituality. Only a saint could hope to influence so saint-like a congregation, and it is the last crown to the holy and earnest priest that he should have given a retreat to the Sisters of Saint Dominic. On one year it had been Espinas, the Franciscan; on another Father Menas, the famous Abbot of Alcantara. But neither of these had caused the suppressed excitement which filled the convent when it passed from cell to cell that the retreat this year was to be given by no less a man than Father Garcia, the Jesuit.

For Father Garcia was a priest whose name was famous through all Catholic Europe as being a worthy successor to those great men, the Xaviers and Loyolas, who founded the first company of Jesus. He was a preacher; he was a writer; above all he was a martyr, for he had carried the gospel into Thibet and had come back with splintered fingers and twisted wrists as a sign of his devotion. Those mutilated hands raised in exhortation had moved his hearers more than the exhortation itself. In person he was tall, dark, and bent, worn to the bone with self-discipline, with a keen, eager face, and the curved predatory nose of the aggressive Churchman. Once that dark, deep-lined face had grace and beauty; now it had character and power; but in youth or age it was a face which neither man nor woman could look upon with indifference. A pagan sword-cut, which had disfigured the cheek, gave it an additional grace in the eyes of the faithful. So warped, and worn, and haggard was the man’s whole appearance, that one might have doubted whether such a frame could contain so keen and earnest a spirit, had it not been for those flashing dark eyes which burned in the heavy shadows of the tufted brows.

It was those eyes which dominated his hearers, whether they consisted of the profligate society of Lisbon or of the gentle nuns of St. Dominic. When they gleamed fiercely as he denounced sin and threatened the sinner, or when, more seldom, they softened into a serene light as he preached the gospel of love, they forced those who saw them into the emotion which they expressed. Standing at the foot of the altar, with his long black figure and his eager face, he swayed the dense crowd of white-cowled women with every flash of those terrible eyes and with every sweep of that mutilated hand. But most of all he moved the Abbess. Her eyes were never taken from his face, and it was noticed that she, who had seemed for so long to have left all the emotions of this world beneath her, sat now with her wax-like face as white as the cowl which framed it, and that after every sermon she would tremble and shake until her rosary rattled against the wooden front of her prie-dieu. The lay-sister of the refectory, who had occasion to consult the Lady Abbess upon one of those nights, could scarcely believe her eyes when she saw her self-contained Superior sobbing her heart out, with her face buried in her little hard pillow.

At last the week of the retreat was over, and upon the Saturday night each nun was to make her general confession as a preparation for the Communion upon the Sunday morning. One after another these white-gowned figures, whose dress was emblematic of their souls, passed into the confessional, whispered through the narrow grating the story of their simple lives, and listened in deep humility and penitence to the wise advice and gentle admonitions which the old priest, with eyes averted, whispered back to them. So in their due order, lay-sisters, novices, sisters, they came back into the chapel, and waited only for the return of their Abbess to finish the day with the usual vespers.

The Abbess Monica had entered the little dark confessional, and saw through the foot-square wire-latticed opening the side of a grey head, one listening ear, and a claw-like hand which covered the rest of the face. A single candle was burning dimly by the Jesuit’s side, and she heard the faint rustle as he turned over the leaves of his breviary. With the air of one who discloses the most terrible crimes, she knelt, with her head abased in sweet humility, and murmured the few trivial faults which still united her to humanity. So slight they were, and so few, that the priest was wondering in his mind what penance there was which would not be out of all proportion to her innocence, when the penitent hesitated, as if she still had something to say but found it difficult to say it.

“Courage, my sister,” said Father Garcia: “what is there which still remains?”

“What remains,” said she, “is the worst of all.”

“And yet it may not be very serious,” said the confessor reassuringly: “have no fear, my sister, in confiding it to me.”

But still the Abbess hesitated, and when at last she spoke it was in a whisper so low that the hand beyond the grating gathered itself round the ear.

“Reverend father,” she said, “we who wear the garb of the holy Dominic have vowed to leave behind us all thoughts of that which is worldly. And yet I, who am the unworthy Abbess, to whom all others have a right to look for an example, have during all this week been haunted by the memory of one whom I loved—of a man whom I loved, father—in the days so many years ago before I took the veil.”

“My sister,” said the Jesuit, “our thoughts are not always ours to command. When they are such as our conscience disapproves we can but regret them and endeavour to put them away.”

“There lies the blackness of my sin, father. The thoughts were sweet to me, and I could not in my heart wish to put them away. When I was in my cell I did indeed struggle with my own weakness, but at the first words which fell from your lips—”

“From my lips!”

“It was your voice, father, which made me think of what I had believed that I had at last forgotten. Every tone of your voice brought back the memory of Pedro.”

The confessor started at this indiscretion by which the penitent had voluntarily uttered the name of her lover. She heard his breviary flutter down upon the ground, but he did not stoop to pick it up. For some little time there was a silence, and then with head averted he pronounced the penance and the absolution.

She had risen from the cushion, and was turning to go, when a little gasping cry came from beside her. She looked down at the grating, and shrank in terror from the sight. A convulsed face was looking out at her, framed in that little square of oak. Two terrible eyes looked out of it—two eyes so full of hungry longing and hopeless despair that all the secret miseries of thirty years flashed into that one glance.

“Julia!” he cried.

And she leaned against the wooden partition of the confessional, her hand upon her heart, her face sunk. Pale and white-clad, she looked a drooping lily.

“It is you, Pedro,” said she at last. “We must not speak. It is wrong.”

“My duty as a priest is done,” said he. “For God’s sake give me a few words. Never in this world shall we two meet again.”

She knelt down upon the cushion, so that her pale pure face was near to those terrible eyes which still burned beyond the grating.

“I did not know you, Pedro. You are very changed. Only your voice is the same.”

“I did not know you either—not until you mentioned my old name. I did not know that you had taken the veil.”

She heaved a gentle sigh.

“What was there left for me to do?” she said. “I had nothing to live for when you had left me.”

His breath came quick, and harsh through the grating. “When I left you? When you ordered me away,” said he.

“Pedro, you know that you left me.”

The eager, dark face composed itself suddenly, with the effort of a strong man who steadies himself down to meet his fate.

“Listen, Julia,” said he. “I saw you last upon the Plaza. We had but an instant, because your family and mine were enemies. I said that if you put your lamp in your window I would take it as a sign that you wished me to remain true to you, but that if you did not I should vanish from your life. You did not put it.”

“I did put it, Pedro.”

“Your window was the third from the top?”

“It was the first. Who told you that it was the third?”

“Your cousin Alphonso—my only friend in the family.”

“My cousin Alphonso was my rejected suitor.”

The two claw-like hands flew up into the air with a horrible spasm of hatred.

“Hush, Pedro, hush!” she whispered.

“I have said nothing.”

“Forgive him!”

“No, I shall never forgive him. Never! never!”

“You did not wish to leave me, then?”

“I joined the order in the hope of death.”

“And you never forgot me?”

“God help me, I never could.”

“I am so glad that you could not forget me. Oh, Pedro, your poor, poor hands! My loss has been the gain of others. I have lost my love, and I have made a saint and a martyr.”

But he had sunk his face, and his gaunt shoulders shook with his agony.

“What about our lives!” he murmured. “What about our wasted lives!”

The Sisters of St. Dominic still talk of the last sermon which Father Garcia delivered to them—a sermon upon the terrible mischances of life, and upon the hidden sweetness which may come from them, until the finest flower of good may bloom upon the foulest stem of evil. He spoke of the soul-killing sorrow which may fall upon us, and how we may be chastened by it, if it be only that we learn a deeper and truer sympathy for the sorrow of our neighbour. And then he prayed himself, and implored his hearers to pray, that an unhappy man and a gentle woman might learn to take sorrow in such a spirit, and that the rebellious spirit of the one might be softened and the tender soul of the other made strong. Such was the prayer which a hundred of the sisters sent up; and if sweetness and purity can aid it, their prayer may have brought peace once more to the Abbess Monica and to Father Garcia of the Order of Jesus.