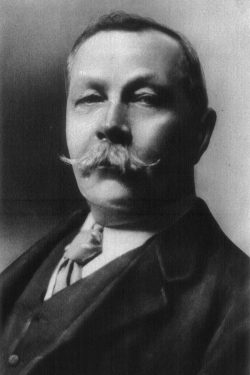

A Regimental Scandal by Arthur Conan Doyle

A Regimental Scandal

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Indianapolis Journal, 14 May 1892.

A Regimental Scandal

It was a very painful business. I don’t think any of us have forgotten it or are at all likely to. The morality of the third Carabiniers was as loose as their discipline was tight, and if a man rode straight and was keen on soldiering he might work out his private record to his own mind. But still there is a limit to what even such a thoroughgoing old sportsman as the Colonel could stand, and that limit was passed on the instant that there was a breath of suspicion about fair play at the card table.

Take the mess. They had ridden through the Decalogue as gaily as through Arabi’s guns at Kassassin. Professionally they had made free with other men’s lives. But the unwritten laws of honour lay unbroken amid the shattered commandments. They were short and sharp, and woe to the man who transgressed them. Sporting debts must be paid. There was no such thing as a white feather. Above all, a man must play fair. It was a simple code of ethics, but it commanded an absolute obedience which might have been refused to a more elaborate system.

If there was one man in the mess who could be held up by the youngsters as the embodiment of honour it was Major Errington. He was older than the chief, and having served twice as a volunteer war correspondent and once as a military attaché, he had been shot over by Berdan’s and Manuffcher repeaters, which seemed to us a much more gaudy thing than Jezails or even Egyptian Remingtons. We had all done Egypt and we had all done the Soudan, but when he would begin his modest after-mess anecdote with: “I remember when Gourko crossed the Balkans,” or “I was riding beside the Red Prince’s staff just two days before Gravelotte,” we would feel quite ashamed of our poor “Puzzles” and “Pathans,” and yearn to replace the foreign office by a committee of subalterns of the Carabiniers, all pledged to a spirited policy.

Then our Major was so humble and gentle with it all. That was his only fault as a soldier. He could fight—none better—but he could not be stern. No matter how heinous the crime of the defaulter who was brought before him, and no matter how resolutely he might purse up his features into a frown, there was still something so very human always gleaming from his eyes that the most drunken deserter could not but feel that this, instead of being a commanding officer, was merely a man and a brother. Though far the richest man in the regiment, for he had ample private means, he lived always in the simplest fashion. Some even set him down as parsimonious, and blamed him for it. But most of us saw in it only another example of the Major’s delicacy which made him fear to make others feel poor by showing himself rich. It was no wonder that he was popular. We subalterns worshipped him, and it was to him that we brought all those tiffs and bickerings and misunderstandings which need a little gentle wisdom to set them right. He would sit patiently, with his cheroot reeking from the corner of his mouth and his eyes fixed upon the ceiling, listening to our details, and then would come the quick, “I think that you ought to withdraw the expression, Jones,” or “Under the circumstances, you were quite justified, Hall,” which settled the matter forever. If we had been told that the chief had burgled the regimental plate or that the chaplain had invited the secularist Sergeant Major to tea, we should have been less astonished than at the rumour that Major Errington had been guilty of anything which was dishonourable.

It came about in this way. The chief was a born plunger. Horses, cards, dice—they were all the same to him. He would bet on, or he would bet against, give the odds or take them, but bet he would. It was all very well as long as he stuck to shilling points and half-crown rubs at whist, or made his little book upon the regimental cup; but when he took to American railway scrip, and laid out all his savings on seven per cent bonds which were selling at sixty-two, he started a game where the odds are all on the bank and the dealer sits somewhere near Wall Street. It was no use telling the old man that Monte Carlo was a sound family investment in comparison. He held on grimly until the inevitable came round. The line was squelched by a big capitalist, who wished to buy it, and our chief was left on the very edge of the bankruptcy court, uncertain from week to week how long it might be before he would need to send in his papers. He said nothing, for he was as proud as Lucifer, but he looked bleary about the eyes in the morning, and his tunic did not fit him quite as tight as it used to. Of course, we were very sorry for the poor old chief, but we were sorrier still for his daughter Violet. We were all in love with Violet Lovell, and her grief was a blight to the regiment. She wasn’t such a very pretty girl, either, but she was fresh and bright and sprightly as an English spring, and so sweet, and good, and sympathetic, that she was just the type of womanhood for all of us. She was one of those girls about whom when once you come to know them, you never think whether they are pretty or not. You only know that it is pleasant to be near them, to see their happy faces, to hear their voices, and to have life made sweeter and more beautiful by their presence. That was how we all felt toward Violet—from the old Major to the newly-joined subaltern, with a brand new razor case upon his dressing table. So when that bright face clouded over as the shadow of her father’s troubles fell upon it, we clouded over also, and the mess of the Carabiniers sank into a state from which even the caterer’s Deutz and Guelderman of ’81 was unable to redeem it.

The Major was the most stricken of all. I think that he took the whole matter to heart even more than the Colonel did, although it had been against his strenuous advice that those cursed bonds had been bought. He was an old friend of the chief and he knew that the disgrace of bankruptcy would be the old man’s death blow; but he was fonder still of the chiefs daughter—none of us ever knew how much so, for he was a shy, silent man, and, in his English fashion, he hid away his emotions as though they were shameful vices. Yet, with all his care, we got a little peep into his heart, if only through his grey eyes when he looked at her, and we knew that he was very fond of our Violet.

The chief used to go to his own room after mess, and whoever wished was welcome to follow him there. Major Errington always went, and the two would play écarte by the hour, while we others either made a four at whist, or smoked and looked on. It was worth looking at too. The chief was a fine écarte player, and they were doing all they knew, for they had taken to playing high points. Of course, the chief, bankruptcy or no, was always ready to plank down whatever he had in his pocket upon the turn of a card. But it was something new in Errington. There had been a time when he had refused to play for money at all. Now he closed at once with every challenge, and even seemed to goad his opponent on to higher stakes still. And he played with the air of a man who was anxious about the game—too anxious to be quite good form, considering that there was money upon the table. He was flustered and unlike himself, and more than once he misplayed the cards completely; but still luck was absolutely in his favour and he won. It went against us to see the old man, who had been so hard hit, losing the money which he needed badly to the richest man in the regiment; but still the Major was the soul of honour, and if he did it there must be some very good reason behind it all.

But there was one of our subalterns who was not so sure about that. Second Lieutenant Peterkin was young and small and newly joined, but he was as keen as a razor edge, with the wits of a racing tout of 50 crammed into a boy’s body. He had made a book himself at 9, ridden a winner at 10 and owned one at 13, so that by the time he came our way he was as blasé and shrewd and knowing as any man in the corps. But he had pluck and he was good humoured, so we all got along with him pretty well until he breathed that first word of suspicion against the Major.

It was in the billiard-room one morning and there were six of us there, all subalterns except Austen, who was the junior captain. Austen and Peterkin were knocking the balls about and we others were helping them by sitting on the corner pockets. Suddenly Austen chucked down his cue with a clatter into the corner.

“You’re a damned little liar, Peterkin,” he remarked.

This was interesting, as we had not listened to the context. We came off our perches and stared. Peterkin took up the chalk and gently rubbed the tip of his cue.

“You’ll be sorry for having said that, Captain Austen,” said he. “Shall I?”

“Yes, and you’ll apologise to me for it.”

“Oh indeed!”

“All I ask is that you test the matter for yourself tonight, and that tomorrow we all meet here again at this hour, and that you let these gentlemen know what you think then.”

“They have nothing to do with it.”

“Excuse me, Captain Austen, they have everything to do with it. You used an expression to me a few moments ago in their presence, and you must withdraw it in their presence also. I shall tell them what the matter was about, and then—”

“Not a word!” cried Austen, angrily. “Don’t dare to repeat such a libel!”

“Just as you like, but in that case you must agree to my conditions.”

“Well, I’ll do it. I’ll watch tonight, and I’ll meet you here tomorrow; but I warn you, young Peterkin, that when I have shown up this mare’s nest of yours the regiment will be too hot to hold you!” He stalked out of the room in a passion, while Peterkin chuckled to himself and began to practise the spot stroke, deaf to our questions as to what was the matter.

We were all there to keep our appointment next day. Peterkin had nothing to say, but there was a twinkle in his little, sharp eyes, especially when Austen came in with a very crestfallen expression upon his face.

“Well,” said he, “If I hadn’t seen with my own eyes I should never have believed it, never! Peterkin, I withdraw what I said yesterday. You were right. By God, to think that an officer of this regiment should stoop so low!”

“It’s a bad business,” said Peterkin. “It was only by chance I noticed it.”

“It’s a good thing you did. We must have a public exposure.”

“If it’s a matter affecting the honour of any fellow of the mess it would surely be best to have Major Errington’s opinion,” said Hartridge.

Austen laughed bitterly. “You fellows may as well be told,” said he. “There’s no use in any mystification. Major Errington has, as you may know, been playing high stakes at écarte with the chief. He has been seen, on two evenings in succession, first by Peterkin and then by me, to hide cards and so strengthen his hand after dealing. Yes, yes, you may say what you like, but I tell you that I saw it with my own eyes. You know how short-sighted the chief is. Errington did it in the most barefaced way, when he thought no one was looking. I shall speak to the chief about it. I consider it to be my duty.”

“You had better all come to-night,” said Peterkin, “but don’t sit near the table, or pretend to be watching. Six witnesses will surely be enough to settle it.”

“Sixty wouldn’t make me believe it,” said Hartridge.

Austen shrugged his shoulders. “Well, you must believe your own eyes, I suppose. It’s an awkward thing for a few subalterns to bring such a serious charge against a senior major of twenty years’ service. But the chief shall be warned, and he may take such steps as he thinks best. It’s been going on too long, and to-night should finish it for good and all.”

So that night we were all in the Colonel’s room, when the card table was pushed forward and the two seniors sat down to their écarte as usual. We others sat round the fire with a keen eye on the players. The Colonel’s face was about two shades redder than usual, and his stiff hair bristled up, as it would when he was angry. Austen, too, looked ruffled. It was clear that he had told the chief, and that the chief had not taken it very sweetly.

“What points?” asked the Major.

“Pound a game, as before.”

“Pound a trick, if you like,” suggested the Major.

“Very good. A pound a trick.” The chief put on his pince-nez and shot a keen questioning glance at his antagonist. The Major shuffled and pushed the cards over to be cut.

The first three games were fairly even. The Major held the better cards, but the chief played far the finer game. The fourth game and deal had come round to the Major again, and as he laid the pack down he spread his elbows out so as to screen his hands from me. Austen gave his neighbour a nudge and we all craned our necks. A hand whisked over the pack and Peterkin smiled.

The chief played a knave and the Major took it with a queen. As he put forward his hand to pick up the trick the Colonel sprang suddenly out of his chair with an oath.

“Lift up your sleeve, sir,” he cried. “By—, you have a card under it!”

The Major had sprung up also, and his chair toppled backward onto the floor. We were all on our feet, but neither of the men had a thought for us. The Colonel leaned forward with his thick red finger upon a card which lay face downward upon the table. The Major stood perfectly composed, but a trifle paler than usual.

“I observe that there was a card there, sir,” said he, “but surely you do not mean to insinuate that—”

The Colonel threw his hand down upon the table.

“It’s not the first time,” said he.

“Do you imagine that I would take an unfair advantage of you?”

“Why, I saw you slip the card from the pack—saw it with my own eyes.”

“You should have known me better after twenty years,” said Major Errington, gently. “I say sir, that you should have known me better, and that you should have been less ready to come to such a conclusion. I have the honour to wish you good evening, sir.” He bowed very gravely and coldly and walked from the room.

But he had hardly closed the door when the curtains at the other end, which separated the card room from the little recess where Miss Lovell was pouring out our coffee, were opened, and she stepped through. She had not a thought for any of us, but walked straight up to her father.

“I couldn’t help hearing you, Dad,” said she. “I am sure that you have done him a cruel injustice.”

“I have done him no injustice. Captain Austen, you were watching. You will bear me out.”

“Yes, sir, I saw the whole affair. I not only saw the card taken, but I saw which it was that he discarded from his hand. It was this one.” He leaned forward and turned up the top card.

“That one!” shouted the chief; “why that is the king of trumps.”

“So it is.”

“But who in his senses would discard the king of trumps; what did he exchange?” He turned up the card on the table. It was an eight. He whistled and passed his fingers through his hair.

“He weakened his hand,” said he. “What was the meaning of that?”

“The meaning is that he was trying to lose, Dad.”

“Upon my word, sir, now that I come to think of it, I am convinced that Miss Lovell is perfectly correct,” said Captain Austen. “That would explain why he suggested high points, why he played such a vile game, and why, when he found that he had such good cards in his hand that he could not help winning, he thought himself justified in getting rid of some of them. For some reason or other he was trying to lose.”

“Good Lord!” groaned the Colonel, “what can I say to put matters straight?” and he made for the door.

And so our little card scandal in the Carabiniers was brought to an honourable ending, for all came out as it had been surmised. Ever since the Colonel’s financial misfortunes his comrade’s one thought had been to convey help to him, but finding it absolutely impossible to do it directly he had tried it by means of the card table. Finding his efforts continually foiled by the run of good cards in his hands he had broken our usual calm by his clumsy attempts to weaken himself. However, American railway bonds are up to 87 now, owing to the providential death of the American millionaire, and the Colonel is no longer in need of any man’s help. The Major soon forgave him for his mistake, and for a time hoped that Violet would have been the pledge of reconciliation—and no match would have been more popular in the regiment—but she destroyed the symmetry of things by marrying a young Madras Staff Corps man, home on leave, so our senior major is still a bachelor, and likely to remain so.