A True Story of the Tragedy of Flowery Land by Arthur Conan Doyle

A True Story of the Tragedy of Flowery Land

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Louisville Courier-Journal, 10 March 1899.

A True Story of the Tragedy of Flowery Land

A steam tug was puffing wheezily in front of the high-masted barque-rigged clipper. With her fresh painted glistening black sides, her sharp sloping bows and her cut-away counter she was the very picture of a fast, well-found ocean-going sailing ship, but those who knew anything about her may have made her the text of a sermon as to how the British seaman was being elbowed out of existence. In this respect she was the scandal of the river. Chinamen, French, Norwegian, Spaniards, Turks—she carried an epitome of the human race. They were working hard cleaning up the decks and fastening down the hatches, but the big burly mate tore his hair when he found that hardly a man on board could understand an order in English.

Capt. John Smith had taken his younger brother, George Smith, as a passenger and companion for the voyage, in the hope that it might be beneficial to his health. They were seated now at each side of the round table, an open bottle of champagne between them, when the mate came in answer to a summons, his eyes still smouldering after his recent outburst.

“Well, Mr. Karswell,” said the captain, “we have a long six months before us, I dare say, before we raise the light of Singapore. I thought you might like to join us in a glass to our better acquaintance and to a lucky voyage.”

He was a jovial, genial soul, this captain, with good humour shining from his red weather-stained face. The mate’s gruffness relaxed before his kindly words and he tossed off the glass of champagne which the other had filled for him.

“How does the ship strike you, Mr. Karswell?” asked the captain.

“There’s nothing the matter with the ship, sir.”

“Nor with the cargo, either,” said the captain. “Champagne we are carrying—a hundred dozen cases. Those and bales of cloth are our main lading. How about the crew, Mr. Karswell?” The mate shook his head.

“They’ll need thrashing into shape, and that’s a fact, sir. I’ve been hustling and driving ever since we left the pool. Why, except oursleves here and Taffir, the second mate, there’s hardly an Englishman aboard. The steward, the cook and the boy are Chinese, as I understand. Anderson, the carpenter, is a Norwegian. There’s Early, the lad, he’s English. Then there’s one Frenchman, one Finn, one Turk, one Spaniard, one Greek and one negro, and as to the rest I don’t know what they are, for I never saw the match of them before.”

“They are from the Philippine Islands, half Spanish, half Malay,” the captain answered. “We call them Manila men, for that’s the port they all hail from. You’ll find them good enough seamen, Mr. Karswell. I’ll answer for it that they work well.”

“I’ll answer for it, too,” said the big mate, with an ominous clenching of his great red fist.

Karswell was hard put to it to establish any order amongst the strange material with which he had to work. Taffir, the second mate, was a mild young man, a good seaman and a pleasant companion, but hardly rough enough to bring this unruly crew to heel. Karswell must do it or it would never be done. The others he could manage, but the Manila men were dangerous. It was a strange type, with flat Tartar noses, small eyes, low brutish foreheads and lank, black hair like the American Indians. Their faces were of a dark coffee tint, and they were all men of powerful physique. Six of these fellows were on board, Leon, Blanco, Duranno, Santos, Lopez and Marsolino, of whom Leon spoke English well and acted as interpreter for the rest. These were all placed in the mate’s watch together with Watto, a handsome young Levantine, and Carlos, a Greek. The more tractable seamen were allotted to Taffir for the other watch. And so, on a beautiful July day, holiday makers upon the Kentish downs saw the beautiful craft as she swept past the Goodwins—never to be seen again, save once, by human eyes.

The Manila men appeared to submit to discipline, but there were lowering brows and sidelong glances which warned their officers not to trust them too far. Grumbles came from the forecastle as to the food and water—and the grumbling was perhaps not altogether unreasonable. But the mate was a man of hard nature and prompt resolution, and the malcontents got little satisfaction or sympathy from him. One of them, Carlos, the Spaniard, endeavoured to keep his bunk upon a plea of illness, but was dragged on deck by the mate and triced up by the arms to the bulwarks. A few minutes afterward Capt. Smith’s brother came on deck and informed the captain what was going on forward. He came bustling up, and having examined the man he pronounced him to be really unwell and ordered him back to his bunk, prescribing some medicine for him. Such an incident would not tend to preserve discipline, or to uphold the mate’s authority with the crew. On a later occasion this same Spaniard began fighting with Blanco, the biggest and most brutal of the Manila men, one using a knife and the other a handspike. The two mates threw themselves between them, and in the scuffle the first mate felled the Spaniard with his fist. In the meantime the barque passed safely through the bay and ran south as far as the latitude of Cape Blanco upon the African coast. The winds were light, and upon the 10th of September, when they had been six weeks out, they had only attained latitude 19 degrees south and longitude 36 degrees west. On that morning it was that the smouldering discontent burst into a most terrible flame.

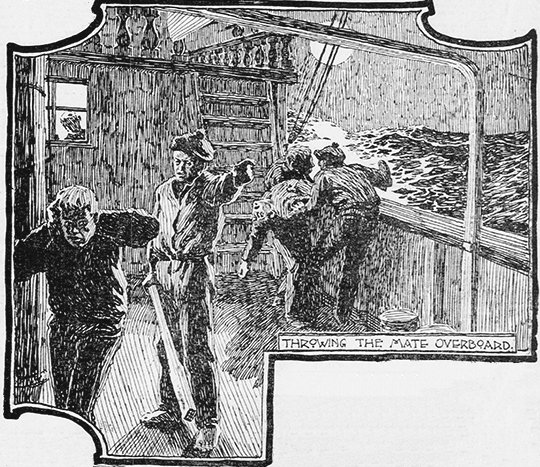

The mate’s watch was from one to four, during which dark hours he was left alone with the savage seamen whom he had controlled. No lion-tamer in a cage could be in more imminent peril, for death might be crouching in wait for him in any of those black shadows which mottled the moonlit deck. Night after night he had risked it until immunity had perhaps made him careless, but now at last it came. At six bells or three in the morning—about the time when the first grey tinge of dawn was appearing in the Eastern sky, two of the mulattos, Blanco and Duranno, crept silently up behind the seaman, and struck him down with handspikes. Early, the English lad, who knew nothing of the plot was looking out on the forecastle head at the time. Above the humming of the foresail above him and the lapping of the water, he heard a sudden crash, and the voice of the mate calling murder. He ran aft, and found Duranno, with horrible persistence, still beating the mate about the head. When he attempted to interfere, the fellow ordered him sternly into the deckhouse, and he obeyed. In the deckhouse the Norwegian carpenter and Candereau, the French seaman, were sleeping, both of whom were among the honest men. The boy Early told them what had occurred, his story being corroborated by the screeches of the mate from the outside. The carpenter ran out and found the unfortunate fellow with his arm broken and his face horribly mutilated.

“Who’s that?” he cried, as he heard steps approaching. “It’s me—the carpenter.”

“For God’s sake get me into the cabin!”

The carpenter had stooped, with the intention of doing so, but Marsolino, one of the conspirators, hit him on the back of the neck and knocked him down. The blow was not a dangerous one, but the carpenter took it as a sign that he should mind his own business, for he went back with impotent tears to his deckhouse. In the meanwhile Blanco, who was the giant of the party, with the help of another mutineer, had raised Karswell, and hurled him, still yelling for help, over the bulwarks into the sea. He had been the first attacked but he was not the first to die.

The first of those below to hear the dreadful summons from the deck was the Captain’s brother, George Smith—the one who had come for a pleasure trip. He ran up the companion and had his head beaten to pieces with handspikes as he emerged. Of the personal characteristics of this pleasure tripper the only item which has been handed down is the grim fact that he was so light that one man was able to throw his dead body overboard. The Captain had been aroused at the same time and had rushed from his rooms into the cabin. Thither he was followed by Leon, Watto and Lopez, who stabbed him to death with their knives. There remained only Taffir, the second mate, and his adventures may be treated with less reticence since they were happier in their outcome.

He was awakened in the first grey of dawn by the sounds of smashing and hammering upon the companion. To so experienced a seaman those sounds at such an hour could have carried but one meaning, and that the most terrible which an officer at sea can ever learn. With a sinking heart, he sprang from his bunk and rushed to the companion. It was choked by the sprawling figure of the captain’s brother, upon whose head a rain of blows was still descending. In trying to push his way up, Taffir received a crack which knocked him backwards. Half distracted he rushed back into the cabin and turned down the lamp, which was smoking badly—a graphic little touch which helps us to realise the agitation of the last hand which lit it. He then caught sight of the body of the captain pierced with many stabs and lying in his blood-mottled nightgown upon the carpet. Horrified at the sight he ran back into his berth and locked the door, waiting in a helpless quiver of apprehension for the next move of the mutineers. He may not have been of a very virile character, but the circumstances were enough to shake the most stout-hearted. It is not an hour at which a man is at his best, that chill hour of the opening dawn, and to have seen the two men, with whom he had supped the night before, lying in their blood, seems to have completely unnerved him. Shivering and weeping he listened with straining ears for the footsteps which would be the forerunners of death.

At last they came, and of half a dozen men at least, clumping heavily down the brass-clamped steps of the companion. A hand beat roughly upon his door and ordered him out. He knew that his frail lock was no protection, so he turned the key and stepped forth. It might well have frightened a stouter man, for the murderers were all there. Leon, Carlos, Santos, Blanco, Duranno, Watto, dreadful looking folk most of them at the best of times, but now, armed with their dripping knives and crimson cudgels, and seen in that dim morning light, as terrible a group as ever a writer of romance conjured up in his imagination. The Manila men stood in a silent semi-circle round the door, with their savage Mongolian faces turned upon him.

“What are you going to do with me?” he cried. “Are you going to kill me?” He tried to cling to Leon as he spoke, for as the only one who could speak English he had become the leader.

“No,” said Leon. “We are not going to kill you. But we have killed the captain and the mate. Nobody on board knows anything of navigation. You must navigate us to where we can land.”

The trembling mate, hardly believing the comforting assurance of safety, eagerly accepted the commission.

“Where shall I navigate you to?” he asked.

There was a whispering in Spanish among the dark-faced men, and it was Carlos who answered in broken English.

“Take up River Platte,” said he. “Good country! Plenty Spanish!” And so it was agreed.

And now a cold fit of disgust seemed to have passed through those callous ruffians for they brought down mops and cleaned out the cabin. A rope was slung round the captain and he was hauled on deck. Taffir, to his credit be it told, interfering to impart some decency to the ceremony of his burial. “There goes the captain!” cried Watto, the handsome Levantine lad, as he heard the splash of the body. “He’ll never call us names any more!” Then all hands were called into the saloon with the exception of Candereau, the Frenchman, who remained at the wheel. Those who were innocent had to pretend approval of the crime to save their own lives. The captain’s effects were laid out upon the table and divided into seventeen shares. Watto insisted that it should only be eight shares, as only eight were concerned in the mutiny, but Leon with greater sagacity argued that everyone should be equally involved in the crime by taking their share of the booty. There were money and clothes to divide, and a big box of boots which represented some little commercial venture of the captain’s. Everyone was stamping about in a new pair. The actual money came to about ten pounds each and the watch was set aside to be sold and divided later. Then the mutineers took permanent possession of the cabin, the course of the ship was altered for South America, and the ill-fated barque began the second chapter of her infamous voyage.

The cargo had been breached and the decks were littered with open cases of champagne, from which everyone helped himself as he pleased. There was a fusillade of popping corks all day, and the air was full of the faint, sweet, sickly smell of the wine. The second mate was nominally commander, but he was commander without the power to command. From morning to night he was threatened and insulted, and it was only Leon’s interference and the well-grounded conviction that they could never make the land without him, which saved him from their daily menaces. They gave a zest to their champagne carousals by brandishing their knives in his face. All the honest men were subjected to the same treatment. Santos and Watto came to the Norwegian carpenter’s whetstone to sharpen their knives, explaining to him as they did so that they would soon use them on his throat. Watto, the handsome lad, declared that he had already killed sixteen men. He wantonly stabbed the inoffensive Chinese steward through the fleshy part of the arm. Santos said to Candereau, the Frenchman, “In two or three days I shall kill you.”

“Kill me then!” cried Candereau with spirit.

“This knife,” said the bully, “will serve you the same that it has the captain.”

There seems to have been no attempt upon the part of the nine honest men to combine against the eight rogues. As they were all of different races and spoke different languages it is not surprising that they were unable to make head against the armed and unanimous mutineers.

And then there befell one of those incidents which break the monotony of long sea voyages. The topsails of a ship showed above the horizon and soon there rose her hull. Her course would take her across her bows, and the mate asked leave to hail her, as he was doubtful as to his latitude.

“You may do so,” said Leon. “But if you say a word about us you are a dead man.”

The strange ship hauled her yard aback when she saw that the other wished to speak to her, and the two lay rolling in the Atlantic swell within a hundred yards of each other.

“We are the Friend, of Liverpool,” cried an officer. “Who are you?”

“We are the Louisa, seven days out from Dieppe for Valparaiso,” answered the unhappy mate, repeating what the mutineers whispered to him. The longitude was asked and given, and the two vessels parted company. With yearning eyes the harassed man looked at the orderly decks and the well served officer of the Liverpool ship, while he in turn noticed with surprise those signs of careless handling which would strike the eye of a sailor in the rig and management of the Flowery Land. Soon the vessel was hull down upon the horizon, and in an hour the guilty ship was again alone in the vast ring of the ocean.

This meeting was very nearly being a fatal one to the mate, for it took all Leon’s influence to convince the other ignorant and suspicious seamen that they had not been betrayed. But a more dangerous time still was before him. It must have been evident to him that when they had made their landfall then was the time when he was no longer necessary to the crew and when they were likely to silence him forever. That which was their goal was likely to prove his death warrant. Every day brought him nearer to this inevitable crisis, and then at last on the night of the 2nd of October the look-out man reported land ahead. The ship was at once put about, and in the morning the South American coast was a dim haze upon the western horizon. When the mate came upon deck he found the mutineers in earnest conclave about the forehatch, and their looks and gestures told him that it was his fate which was being debated. Leon was again on the side of mercy. “If you like to kill the carpenter and the mate, you can: I shall not do it,” said he. There was a sharp difference of opinion upon the matter, and the poor, helpless mate waited, like a sheep near a knot of butchers.

“What are they going to do with me?” he cried to Leon, but received no reply. “Are they going to kill me?” he asked Marsolino.

“I am not, but Blanco is,” was the discouraging reply.

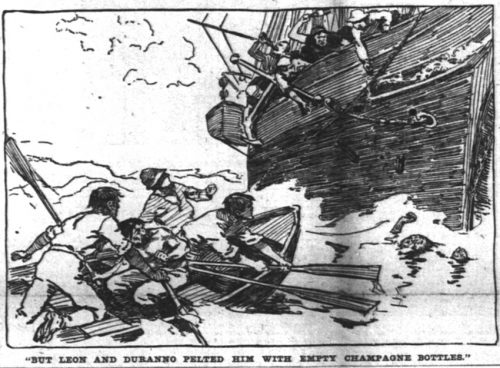

However, the thoughts of the mutineers were happily diverted by other things. First they ckwed up the sails and dropped the boats alongside. The mate having been deposed from his command there was no commander at all, so that everything was chaos. Some got into the boats and some remained upon the decks of the vessel. The mate found himself in one boat which contained Watto, Paul the Sclavonian, Early the ship’s boy and the Chinese cook. They rowed a hundred yards away from the ship, but were recalled by Blanco and Leon. It shows how absolutely the honest men had lost their spirit, that though they were four to one in this particular boat they meekly returned when they were recalled. The Chinese cook was ordered on deck, and the others were allowed to float astern. The unfortunate steward had descended into another boat, but Duranno pushed him overboard. He swam for a long time begging hard for his life, but Leon and Duranno pelted him with empty champagne bottles from the deck until one of them struck him on the head and sent him to the bottom. The same men took Cassap, the little Chinese boy, into the cabin. Candereau, the French sailor heard him cry out: “Finish me quickly then!” and they were the last words that he ever spoke.

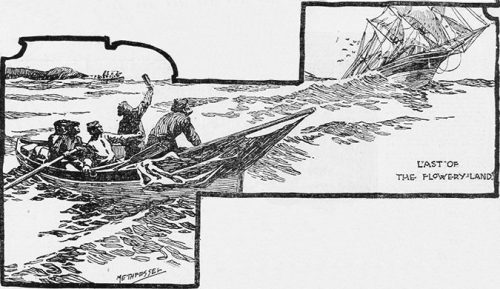

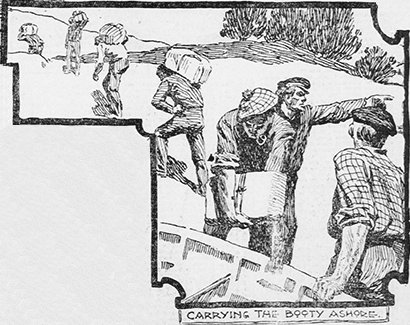

In the meantime the carpenter had been led into the hold by the other mutineers and ordered to scuttle the ship. He bored four holes forward and four aft, and the water began to pour in. The crew sprang into the boats, one small one, and one large one, the former in tow of the latter. So ignorant, and thoughtless were they that they were lying alongside as the ship settled down in the water, and would infallibly have been swamped if the mate had not implored them to push off. The Chinese cook had been left on board, and had clambered into the tops so that his gesticulating figure was almost the last that was seen of the ill-omened Flowery Land as she settled down under the leaping waves. Then the boats, well laden with plunder, made slowly for the shore.

It was 4 in the afternoon upon the 4th of October that they ran their boats upon the South American beach. It was a desolate spot, so they tramped inland, rolling along with the gait of seamen ashore, their bundles upon their shoulders. Their story was that they were the shipwrecked crew of an American ship from Peru to Bordeaux. She had foundered a hundred miles out, and the captain and officers were in another boat which had parted company. They had been five days and nights upon the sea. Toward evening they came upon the estancia of a lonely farmer to whom they told their tale, and from whom they received every hospitality. Next day they were all driven over to the nearest town of Rocha. Candereau and the mate got an opportunity of escaping that night, and within twenty-four hours their story had been told to the authorities and the mutineers were all in the hands of the police.

Of the twenty men who had started from London in the Flowery Land six had met their deaths from violence. There remained fourteen, of whom eight were mutineers, and six were destined to be the witnesses against them. No more striking example could be given of the long arm and steel hand of the British law than that within a few months this mixed crew, Sclavonian, negro, Manila men, Norwegian, Turk and Frenchman, gathered on the shore of the distant Argentine, were all brought face to face at the Central Criminal Court in the heart of London town.

The trial excited great attention on account of the singular crew and the monstrous nature of their crimes. The death of the officers did less to rouse the prejudice of the public and to influence the jury than the callous murder of the unoffending Chinaman. The great difficulty was that of apportioning the blame amongst so many men and of determining which had really been active in the shedding of blood. Taffir, the mate: Early, the ship’s boy: Candereau, the Frenchman, and Anderson, the carpenter, all gave their evidence, some incriminating one and some another. After a very careful trial five of them, Leon, Blanco, Watto, Duranno and Lopez, were condemned to death. They were all Manila men, with the exception of Watto, who came from the Levant. The oldest of the prisoners was only five and twenty years of age. They took their sentence in a perfectly callous fashion, and immediately before it was pronounced Leon and Watto laughed heartily because Duranno had forgotten the statement which he had intended to make. One of the prisoners who had been condemned to imprisonment was at once heard to express a hope that he might be allowed to have Blanco’s boots.

The sentence of the law was carried out in front of Newgate upon the 22nd of February. Five ropes jerked convulsively for an instant, and the tragedy of the Flowery Land had reached its fitting consummation.