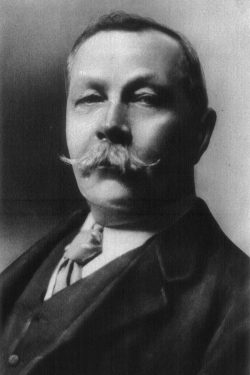

The Colonel’s Choice by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Colonel’s Choice

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper, 26 July 1891.

The Colonel’s Choice

There was some surprise in Birchespool when so quiet and studious a man as Colonel Bolsover became engaged to the very dashing and captivating Miss Hilda Thornton. And in truth this surprise was mingled with some feeling of pity for the gallant officer. It was not that anything really damaging could be alleged against the young lady. Her birth at least was excellent, and her accomplishments undeniable. But for some years she had been mixed up with a circle of people whose best friends could not deny that they were fast. “Smart” they preferred to call themselves, but the result was much the same.

Hilda Thornton was a very lovely woman of the blonde, queenly, golden-haired type. She was the belle of the garrison, and each fresh subaltern who came up from Woolwich or from Sandhurst bowed down and adored her. Yet subalterns grew into captains and captains into majors without a change in her condition. An interminable succession of sappers, gunners, cavalrymen and linesmen filed past through the social life of Birchespool, but Miss Hilda Thornton remained Miss Hilda still. Already she had begun to show a preference for subdued lights, and to appear some years younger in the evening than in the morning, when good, simple-hearted Colonel Bolsover, in one of his brief sallies into the social world, recognising in her all that was pure and fresh, with much diffidence made her the offer of an honoured name, a good position, and some two thousand a year. It is true that there were a grizzled head and an Indian constitution to set off against these advantages, but the young lady showed no hesitation, and the engagement was the talk next day of all the mess-rooms and drawing-rooms of the little town.

But even now it was felt that there was a doubt as to her ultimate marriage. Spinsters whispered dark prophecies upon the subject, and sporting ensigns had money on the event. Twice already had Hilda approached the happy state, and twice there had been a ring returned, and a pledge unfulfilled. The reason of these fiascos had never been made plain. There were some who talked of the fickleness and innate evil of mankind. Others spoke of escapes, and hinted at sinister things which had come to the horrified ears of her admirers, and had driven them from her side. Those who knew most said least, but they shook their heads sadly when the colonel’s name was mentioned.

Just six days before the time fixed for the marriage Colonel Bolsover was seated in his study with his cheque-book upon the desk in front of him, glancing over the heavy upholsterer’s bills, which had already commenced to arrive, when he received a visit from his very old friend, Major Barnes, of the Indian horse. They had done two campaigns together on the frontier, and it was a joy to Bolsover to see the dark, lean face and the spare, wiry figure of the Bengal Lancer.

“My dear boy,” he cried, with outstretched hands. “I did not even know that you were in England.”

“Six months’ furlough,” answered his old comrade, returning his greeting warmly. “Had a touch of liver in Peshawar, and a board thought that a whiff of the old air might stiffen me up. But you are looking well, Bolsover.”

“So I should Barnes. I have had some good fortune lately, better fortune than I deserve. Have you heard it? You may congratulate me, my boy. I am a Benedict from next Wednesday.”

The Indian soldier grasped the hand which was held out to him, but his grip was slack and his eyes averted.

“I’m sure I hope it is all for the best, Bolsover.”

“For the best? Why, man, she is the most charming girl in England. Come in this evening and be introduced.”

“Thank you, Bolsover, I think that I have already met the young lady. Miss Hilda Thornton, I believe? I dined with the Sappers last night and heard the matter mentioned.”

Barnes was talking in a jerky, embarrassed style, which was very different to his usual free and frank manner. He paused to pick his words, and scraped his chin with his finger and thumb. The colonel glanced at him with a questioning eye.

“There’s something wrong, Jock,” said he.

“Well, old chap, I have been thinking—we have been thinking—several of your old chums, that is to say—I wish to the Lord they would come and do their own talking—”

“Oh, you’re a deputy?” Bolsover’s mouth set, and his brows gathered.

“Well, you see, we were talking it over, you know, Bolsover, and it seemed to us that marriage is a very responsible kind of thing, you know.”

“Well, you ought to know,” said the colonel, with a half smile. “You have been married twice.”

“Ah, yes, but in each case I give you my word, Bolsover, that I acted with prudence. I knew all about my wife and her people: upon my honour I did!”

“I don’t quite see what you are driving at, Barnes.”

“Well, old chap, I am rather clumsy at anything of this sort. It’s out of my line, but you will forgive me, I am sure. But we can’t see a chum in danger without a word to warn him. I knew Tresillian in India. We shared one tent in the Afghan business. Tresillian knew Miss Thornton, no one better. I have reason to believe that when he was quartered here five years ago—”

Colonel Bolsover sprang from his chair, and threw up a protesting hand.

“Not another word, Barnes,” said he. “I have already heard too much. I believe that you mean well to me, but I cannot listen to you upon this subject. My honour will not permit it.”

Barnes had risen from his chair, and the two old soldiers looked into each other’s eyes.

“You are quite resolved upon this, Bolsover?”

“Absolutely.”

“Nothing would shake you?”

“Nothing on earth.”

“Then that’s an end of it. I won’t say another word. I may be wrong and you may be right. I am sure that I wish you every happiness from the bottom of my heart.”

“Thank you, Jock. But you’ll stay tiffin. It’s almost ready.”

“No, thank you, my boy. I have a cab at the door, and I am off to town. I ought to have started by the early train, but I felt that I could not leave Birchespool without having warned—that is to say congratulated you upon the event. I must run now, but you’ll hear from me by Friday.”

Such was the embassy of Major Jack Barnes, the one and only attempt which was made to shake the constancy of Percy Bolsover. Within a week Hilda Thornton was Hilda Thornton no longer; and amid a pelting storm of rice the happy couple made their way to the Birchespool railway station, en route for the Riviera.

For fifteen months all went well with the Bolsovers. They had taken a large detached villa which stood in its own grounds on the outskirts of Birchespool, and there they entertained, with a frequency and a lavishness which astonished those who had known the soldierly simplicity of the colonel’s bachelor days. Indeed he had not altered in his tastes. A life of frivolity was thoroughly repellent to him. But he was afraid of transplanting his wife too suddenly into an existence which might seem to her to be austere. After all he was nearly twenty years her senior, and was it reasonable to suppose that she could conform her tastes to his? He must sacrifice his own tastes. It was a duty. He must shake off his old ways and his old comforts. He set himself to the task with all the energy and thoroughness of an old soldier, until Bolsover’s dances and Bolsover’s dinners were one of the features of social life in Birchespool.

It was in the second winter after their marriage that the great ball was given in the little town on account of a very august and Royal visitor. The cream of the county had joined with the garrison to make it a brilliant success. Beautiful women were there in plenty. But Bolsover thought as he gazed upon the dancers that there was none who could compare with his own wife. In a grey tulle toilette, trimmed with apple-blossom, with a diamond aigrette twinkling from amid her golden hair, she might have stood as the very type and model of the blonde regal Anglo-Saxon beauty. In this light the first faint traces of time were smoothed away, and, with a gleam of pleasure in her eyes, and a dash of colour in her cheeks, she was so lovely that even the Royal and august, though reported to be very blasé in the matter of beauty, was roused to interest. The colonel stood among the palms and the rhododendrons, following her with his eyes, and thrilling with pride as he noticed how heads turned and quick whispers were exchanged as she passed through the crowd.

“You are to be congratulated, colonel,” said Lady Shipton, the wife of the general of the brigade. “Madame is quite our belle to-night.”

“I am very flattered to hear you say so,” said the colonel, rubbing his hands in his honest delight.

“Ah, you know that you think so yourself,” said the lady, archly, tapping his arm with her fan. “I have been watching your eyes.”

The colonel coloured slightly and laughed. “She certainly seems to be enjoying herself,” he remarked. “She is a little hard to please in the matter of partners, and when I see her dance twice with the same I know that she is satisfied.”

The lady looked, and a slight shadow crossed her face. “Oh, her partner!” she exclaimed. “I did not notice him.”

“He looks like a man who has been hard hit at some time,” observed the colonel. “Do you know him?”

“Yes. He used to be stationed here before you came. Then he got an appointment and went to India. Captain Tresillian is his name, of the Madras Staff corps.”

“Home on leave, I suppose!”

“Yes. He only arrived last week.”

“He needed a change,” observed the colonel. “But the band is rather overpowering here. This next is the ‘Lancers.’ May I have the pleasure?”

The face which had attracted the colonel’s attention was indeed a remarkable one—swarthy, keen, and hawklike, with sunken cheeks and deep set eyes, which were Italian rather than English in their blackness and brightness. The Celtic origin of his old Cornish blood showed itself in his thin, wiry figure, his nervous, mobile features, and the little petulant gestures with which he lent emphasis to his remarks. Hilda Bolsover had turned pale to the lips at the sight of him as she entered the ballroom, but now they had danced two consecutive dances, and the third they had sat out under the shadow of the palms. There the colonel found them as he strolled round the room while the dancers were forming up for the cotillon.

“Why, Hilda, this is one of your favourites,” said he. “You are surely not going to miss it?”

“Thank you, Percy; but I am a little tired. May I introduce you to my old friend, Captain Tresillian, of the Indian army! You may have heard me speak of him. I have known him for ever so many years.”

Colonel Bolsover held out his hand cordially, but the other swung round his shoulder, and gazed vacantly across the ballroom as though he had heard nothing. Then suddenly, with a half shrug, like a man who yields to his fate, he turned and took the hand which was offered to him. The colonel glanced at him in some surprise, for his manner was strange, his eyes wild, and his grasp burned like that of a man in a fever.

“You have not been home long, I believe?”

“Got back last week in the Jumna.”

“Had you been away long?”

“Only three years.”

“Oh! Then you found little changed at home?”

Captain Tresillian burst into a harsh laugh.

“Oh, yes; I find plenty of change at home. Plenty of change. Things are very much altered.”

His swarthy face had darkened, and his thin, dark hands were nervously opening and shutting.

“I think, Percy,” said Hilda Bolsover, “that the carriage will be waiting now. Good night, Captain Tresillian. I am sure that we shall be happy to see you at Melrose Lodge.”

“Most certainly,” cried the colonel. “Any friend of my wife’s is a welcome guest. When may we hope to see you?”

“Yes, yes; I shall certainly call,” the other answered, “I am very much obliged to you. Good night.”

“Do you know, Hilda,” remarked the colonel, as they rattled homewards that night in their brougham, “I notice something very strange in the manner of your friend, Captain Tresillian. He struck me as a very nice fellow, you know, but his talk and his look were just a little wild at times. I should think he has had a touch of the sun in India.”

“Very possibly. He has had some trouble, too, I believe.”

“Ah, that might account for it. Well, we must try and make the place as pleasant to him as we can.”

Hilda said nothing, but she put her arms round her husband’s neck and kissed him.

The very next day and for many days after Captain Tresillian called at Melrose Lodge. He walked with Hilda, he rode with her, he chatted with her in the garden, and he escorted her out when the colonel was away at his duties. In a week there was gossip about it in Birchespool: in a month it was the notorious patent scandal of the town. Brother veterans sniggered about it, women whispered, some pitied, some derided; but amid all the conflict of opinions Bolsover alone seemed to be absolutely unconcerned. Once only Lady Shipton ventured to approach the subject with him, but he checked her as firmly as, if more gently than, he had his old friend in the days of his engagement. “I have implicit faith in her,” he said. “I know her better than anyone else can do.”

But there came a day when the colonel, too, found that he could no longer disregard what was going on beneath his roof. He had come back late one afternoon, and had found Captain Tresillian installed as usual in the drawing-room, while his wife sat pouring out tea at the small table by the fire. Their voices had sounded in brisk talk as he had entered, but this had tailed off to mere constraint and formalities. Bolsover took his seat by the window, thoughtfully stirring the cup of tea which his wife had handed to him, and glancing from time to time at Tresillian. He noticed him draw his note-book from his pocket, and scribble a few words upon a loose page. Then he saw him rise with his empty cup, step over to the table with it, and hand both it and the note to her. It was neatly done, but her fingers did not close upon it quickly enough, and the little slip of white paper fluttered down to the ground. Tresillian stooped for it, but Bolsover had taken a step forward, and had snatched it from the carpet.

“A note for you, Hilda,” said he quietly, handing it to her. His words were gentle, but his mouth had set very grimly, and there was a dangerous glitter in his eyes.

She took it in her hand and then held it out to him again. “Won’t you read it out to me?” said she.

He took it and hesitated for an instant. Then he threw it into the fire. “Perhaps it is better unread,” said he. “I think, Hilda, you had best step up to your room.”

There was something in his quiet, self-contained voice which dominated and subdued her. He had an air and a manner which was new to her. She had never seen the sterner side of his character. So he had looked and spoken on the fierce day before the Delhi Gates, when the Sepoy bullets were hopping like peas from the tires of his gun, and Nicholson’s stormers were massing in the trenches beneath him. She rose, shot a scared, half-reproachful glance at Tresillian, and left the two men to themselves.

The colonel closed the door quickly behind her, and then turned to his visitor.

“What have you to say?” he asked, sternly and abruptly.

“There was no harm in the note.” Tresillian was leaning with his shoulder against the mantelpiece, a sneering, defiant expression upon his dark, haggard face.

“How dare you write a note surreptitiously to my wife? What had you to say which might not be spoken out?”

“Well, really, you had the opportunity of reading it. You would have found it perfectly innocent. Mrs. Bolsover, at any rate, was not in the least to blame.”

“I do not need your assurance on that point. It is in her name as much as in my own that I ask you what you have to say.”

“I have nothing to say, except that you should have read the note when you had the chance.”

“I am not in the habit of reading my wife’s correspondence. I have implicit confidence in her, but it is one of my duties to protect her from impertinence. When I first joined the service there was a way by which I could have done so. Now I can only say that I think you are a blackguard, and that I shall see that you never again cross my threshold, or that of any other honest man in this town, if I can help it.”

“You show your good taste in insulting me when I am under your roof,” sneered the other. “I have no wish to enter your house, and as to the other thing you will find me very old-fashioned in my ideas if you should care to propose anything of the kind. I wish you good-day.”

He took up his hat and gloves from the piano, and walked to the door. There he turned round with his hand upon the handle and faced Bolsover with a face which was deeply lined with passion and with misery.

“You asked me once whether I found things different in England. I told you that I did. Now I will tell you why. When I was in England last I loved a girl and she loved me—she loved me, you understand. There was a secret engagement between us. I was poor, with nothing but my pay, and she had been accustomed to every luxury. It was to earn enough to be able to keep her that I volunteered in India, that I worked for the Staff, that I saved and saved, and lived as I believe no British officer ever lived in India yet. I had what I thought was enough at last, and I came back with it. I was anxious, for I had had no word from my girl. What did I find? That she had been bought by a man twice my age—bought as you would buy—.” He choked and put out a hand to his throat before he could find his voice. “You complain—you pose as being injured,” he cried. “I call God to witness which has most reason to cry out, you or I.”

Colonel Bolsover turned and rang the bell. Before the servant could come, however, his visitor was gone, and he heard the quick scrunch of his feet on the gravel without. For a time he sat with his chin on his hands, lost in thought. Then he rose and ascended to his wife’s boudoir.

“I want to have a word with you, Hilda,” said he, taking her hand, and sitting down beside her on the settee. “Tell me truly now, are you happy with me?”

“Why, Percy, what makes you ask?”

“Are you sorry that you married me? Do you regret it? Would you wish to be free?”

“Ohl Percy, don’t ask such questions.”

“You never told me that there was anything between you and that man before he went to India.”

“It was quite informal. It was nothing—a mere friendship.”

“He says an engagement.”

“No, no; it was not quite that.”

“You were fond of him?”

“Yes; I was fond of him.”

“Perhaps you are so still?”

She turned away her face, and played with the jingling ornaments of her chatelaine. Her husband waited for an answer, and a spasm of pain crossed his face as no answer came.

“That will do,” said he, gently disengaging his hand from hers. “At least you are frank. I had hoped for too much. I was a fool. But all may yet be set right. I shall not mar your life, Hilda, if I can help it.”

The next day the authorities at the War office were surprised to receive a strongly-worded letter from so distinguished an artillery officer as Percy Bolsover, asking to be included in an expedition which was being fitted out in the North-west of India, and which notoriously promised a great deal of danger and very little credit. There was some delay in the answer, and before it arrived the colonel had reached his end in another and a more direct fashion.

No one will ever know how the fire broke out at Melrose Lodge. It may have been the paraffin in the cellars, or it may have been the beams behind the grate. Whatever the cause the colonel was wakened at two on a winter morning by the choking, suffocating smell of burning wood, and rushing out of his bedroom found that the stairs and all beneath him was already a sea of fire. Shouting to his wife he dashed upstairs, and roused the frightened maids, who came screaming, half-dressed, down into his bedroom.

“Come, Hilda,” he cried, “we may manage the stairs.”

They rushed down together as far as the first landing, but the fire spread with terrible rapidity; the dry woodwork was blazing like tinder, and the swirl of mingled smoke and flame drove them back into the bedroom. The colonel shut the door, and rushed to the window. A crowd had already assembled in the road and the garden, but there were no signs of the engines. A cry of horror and of sympathy went up from the people as they saw the figures at the window, and understood from the flames which were already bursting out from the lower floor that their retreat was already cut off.

But the colonel was too old a soldier to be flurried by danger, or at a loss for a plan. He opened the folding windows and dragging the feather-bed across the floor he hurled it out.

“Hold it under the window,” he cried. And a cheer from below showed that they understood his meaning.

“It is not more than forty feet,” said he, coolly. “You are not afraid, Hilda?”

She was as calm as he was. “No, I am not afraid,” she answered.

“I have a piece of rope here. It is not more than twenty feet, but the feather bed will break the fall. We will pass the maids down first, Hilda. Noblesse oblige!”

There was little time to spare, for the flames were crackling like pistol shots at the further side of the door and shooting little red tongues through the slits. The rope was slung round one maid, under her arms, and she was instructed to slip out from it, and to fall when she had been lowered as far as it would go. The first was unfortunate, for she fell obliquely, bounded from the edge of the bed, and her screams told those above her of her mishap. The second fell straight, and escaped with a shaking. There were only the husband and wife now.

“Step back from the window, Hilda,” said he. He kissed her on the forehead, as a father might a child. “Good-bye, dear,” he said. “Be happy.”

“But you will come after me, Percy?”

“Or go before you,” said he, with a quiet smile. “Now, dear, slip the rope round you. May God watch over you and guard you!”

Very gently he lowered her down, leaning far over the window, that another three feet might be taken from her fall. Bravely and coolly she eyed the bed beneath her, put her feet together, and came down like an arrow into the centre of it. A cheer from beneath told him that she was unhurt. At the same instant there was a crash and a roar behind him, and a great yellow blast of flame burst roaring into the room. The colonel stood framed in the open window, looking down upon the crowd. He leaned with one shoulder against the stonework, with the droop of the head of a man who is lost in thought. Behind him was a lurid background of red flame, and a long venomous tongue came flickering out over his head. A hundred voices screamed to him to jump. He straightened himself up like a man who has taken his final resolution, glanced down at the crowd, and then, turning, sprang back into the flames.

And that was the colonel’s choice. It was “Accidental death” at the inquest, and there was talk of the giddiness of suffocation and the slipping of feet; but there was one woman at least who could tell how far a man who truly loves will carry his self sacrifice.