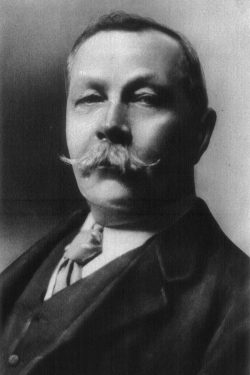

Touch and Go: A Midshipman’s Story by Arthur Conan Doyle

Touch and Go: A Midshipman’s Story

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Cassell’s Family Magazine, April 1886.

Touch and Go: A Midshipman’s Story

What is there in all nature which is more beautiful or more inspiriting than the sight of the great ocean, when a merry breeze sweeps over it, and the sun glints down upon the long green ridges with their crests of snow? Sad indeed must be the heart which does not respond to the cheery splashing of the billows and their roar upon the shingle. There are times, however, when the great heaving giant is in another and a darker mood. Those who, like myself, have been tossed upon the dark waters through a long night, while the great waves spat their foam over them in their fury, and the fierce winds howled above them, will ever after look upon the sea with other eyes. However peaceful it may be, they will see the lurking fiend beneath its smiling surface. It is a great wild beast of uncertain temper and incalculable strength.

Once, and once only, during the long years which I have spent at sea, have I found myself at the mercy of this monster. There were circumstances, too, upon that occasion, which threatened a more terrible catastrophe than the loss of my own single life. I have set myself to write down, as concisely and as accurately as I can, the facts in connection with that adventure and its very remarkable consequences.

In 1868 I was a lad of fourteen, and had just completed my first voyage in the Paraguay, one of the finest vessels of the finest of the Pacific lines, in which I was a midshipman. On reaching Liverpool, our ship had been laid up for a month or so, and I had obtained leave of absence to visit my relations, who were living on the banks of the Clyde. I hurried north with all the eagerness of a boy who has been abroad for the first time, and met with a loving reception from my parents and from my only sister. I have never known any pleasure in life which could compare with that which these reunions bring to a lad whose disposition is affectionate.

The little village at which my family were living was called Rudmore, and was situated in one of the most beautiful spots in the whole of the Clyde. Indeed, it was the natural advantages of its situation which had induced my father to purchase a villa there. Our grounds ran down to the water’s edge, and included a small wooden jetty which projected into the river. Beside this jetty was anchored a small yacht, which had belonged to the former proprietor, and which had been included in the rest of the property when purchased by my father. She was a smart little clipper of about three-ton burden, and directly my eyes fell upon her I determined that I would test her sea-going qualities.

My sister had a younger friend of hers, Maud Sumter, staying with her at this time, and the three of us made frequent excursions about the country, and occasionally put out into the Firth in order to fish. On all these nautical expeditions we were accompanied by an old fisherman named Jock Reid, in whom my father had confidence. At first we were rather glad to have the old man’s company, and were amused by his garrulous chat and strange reminiscences. After a time, however, we began to resent the idea of having a guardian placed over us, and the grievance weighed with double stress upon me, for, midshipman-like, I had fallen a victim to the blue-eyes and golden hair of my sister’s pretty playmate, and I conceived that without our boatman I might have many an opportunity of showing my gallantry and my affection. Besides, it seemed a monstrous thing that a real sailor, albeit only fourteen years of age, who had actually been round Cape Horn, should not be trusted with the command of a boat in a quiet Scottish firth. We put our three youthful heads together over the matter, and the result was a unanimous determination to mutiny against our ancient commander.

It was not difficult to carry our resolution into practice. One bright winter’s day, when the sun was shining cheerily, but a stiffish breeze was ruffling the surface of the water, we announced our intention of going for a sail, and Jock Reid was as usual summoned from his cottage to escort us. I remember that the old man looked very doubtfully at the glass in my father’s hall, and then at the eastern sky, in which the clouds were piling up into a gigantic cumulus.

“Ye maunna gang far the day,” he said, shaking his grizzled head. “It’s like to blow hard afore evening.”

“No, no, Jock,” we cried in chorus; “we don’t want to go far.”

The old sailor came down with us to the boat, still grumbling his presentiments about the coming weather. I stalked along with all the dignity of chief conspirator, while my sister and Maud followed expectantly, full of timidity and admiration for my audacity. When we reached the boat I helped the boatman to set the mainsail and the jib, and he was about to cast her off from her moorings when I played the card which I had been reserving.

“Jock,” I said, slipping a shilling into his hand; “I’m afraid you’ll feel it cold when we get out. You had better get yourself a drop of something before we start.”

“Indeed I will, maister,” said Jock emphatically. “I’m no as young as I was, and the coffee keeps the cold out.”

“You run up to the house,” I said; “we can wait until you come back.”

Poor old Jock, suspecting no treachery, made off in the direction of the village, and was soon out of sight. The instant he had disappeared six busy little hands were at work undoing the moorings, and in less than a minute we were clear of the land, and were shooting gallantly out into the centre of the Firth of Clyde. Under her press of canvas, the little boat heeled over until her lee-gunwale was level with the water, and as we plunged into the waves the spray came showering over the bows and splashing on our deck. Far away on the beach we could see old Jock, who had been warned by the villagers of our flight, running eagerly up and down, and waving his arms in his excitement. How we laughed at the old man’s impotent anger, and what fun we made of the salt foam which wet our faces and sprinkled on our lips! We sang, we romped, we played, and when we tired of this the two girls sat in the sheets, while I held the tiller and told many stories of my nautical experiences, and of the incidents of my one and only voyage.

At first we were somewhat undecided as to what course we should steer, or where we should make for; but after consultation it was unanimously decided that we should run out to the mouth of the Firth. Old Jock had always avoided the open sea, and had beaten about in the river, so it seemed to us, now that we had deposed our veteran commander, that it was a favourable opportunity for showing what we could do without him. The wind, too, was blowing from the eastward, and therefore was favourable to the attempt. We pulled the mainsail as square as possible, and keeping the tiller steady, ran rapidly before the wind in the direction of the sea.

Behind us the great cumulus of clouds had lengthened and broadened, but the sun was still shining brightly, making the crests of the waves sparkle again, like long ridges of fire. The banks of the Firth, which are four or five miles apart, are well wooded, and many a lovely villa and stately castle peeped out from among the trees as we swept past. Far behind us we saw the long line of smoke which told where Greenock and Glasgow lay, with their toiling thousands of inhabitants. In front rose a great stately mountain-peak, that of Goatfell, in Arran, with the clouds wreathed coquettishly round the summit. Away to the north, too, in the purple distance lay ranges of mountains stretching along the whole horizon, and throwing strange shadows as the bright rays of the sun fell upon their rugged sides.

We were not lonely as we made our way down ihe great artery which carries the commerce of the west of Scotland to the sea. Boats of all sizes and shapes passed and re-passed us. Eager little steamers went panting by with their loads of Glasgow citizens, going to or returning from the great city. Yachts and launches, and fishing-boats, came and went in every direction. One of the latter crossed our bows, and one of her crew, a rough-bearded fellow, shouted hoarsely at us; but the wind prevented us from hearing what he said. As we neared the sea a great Atlantic steamer went slowly past us, with her big yellow funnel vomiting forth clouds of smoke, and her whistle blowing to warn the smaller craft to keep out of her way. Her passengers lined the side to watch us as we shot past them, very proud of our little boat and of ourselves.

We had brought some sandwiches away with us, and a bottle of milk, so that there was no reason why we should shorten our cruise. We stood on accordingly until we were abreast of Ardrossan, which is at the mouth of the river and exactly opposite to the island of Arran, which lies in the open sea. The strait across is about eight miles in width, and my two companions were both clamorous that we should cross.

“It looks very stormy,” I said, glancing at the pile of clouds behind us; “I think we had better put back.”

“Oh, do let us go on to Arran!” little Maud cried enthusiastically.

“Do, Archie,” echoed my sister; “surely, you are not afraid?”

To tell the truth, I was afraid, for I read the signs of the weather better than they did. The reproachful look in Maud’s blue eyes at what she took to be my faint-heartedness overcame all my prudence.

“If you wish to go, we’ll go,” I said; and we sailed out from the mouth of the river into the strait.

Hitherto we had been screened from the wind to some extent by the hills behind us, but as we emerged from our shelter it came upon us in fiercer and more prolonged blasts. The mast bent like a whip under the pressure upon the sail, and would, I believe, have snapped short off, had it not been that I had knowledge enough of sailing to be able to take in a couple of reefs in the great sail. Even then the boat lay over in an alarming manner, so that we had to hold on to the weather bulwarks to prevent our slipping off. The waves, too, were much larger than they had been in the Firth, and we shipped so much water that I had to bail it out several times with my hat. The girls clapped their hands and cried out with delight as the water came over us, but I was grave because I knew the danger; and seeing me grave, they became grave too. Ahead of us the great mountain-peak towered up into the clouds, with green woods clustering about its base; and we could see the houses along the beach, and the long shining strip of yellow sand. Behind us the dark clouds became darker, lined at the base with the peculiar lurid tint which is nature’s danger signal. It was evident that the breeze would soon become a gale, and a violent one. We should not lose a moment in getting back to the river, and I already bitterly repented that I had ever left its sheltering banks.

We put the boat round with all the speed we could, but it was no light task for three children. When at last we began to tack for the Scotch coast, we realised how difficult a matter it was for us to return. As long as we went with the wind, we went also with the waves; and it was only a stray one which broke over us. The moment, however, that we turned our broadside towards the sea we were deluged with water, which poured in faster than we could bail it out. A jagged flash of lightning clove the dark eastern sky, followed by a deafening peal of thunder. It was clear that the gale was about to burst; and it was evident to me that if it caught us in our present position we should infallibly be swamped. With much difficulty we squared our sail once more, and ran before the wind. It had veered a couple of points to the north, so that our course promised to take us to the south of the island. We shipped less water now than before, but on the other hand, every minute drove us out into the wild Irish Sea, further and further from home.

It was blowing so hard by this time, and the waters made such a clashing, that it was hard to hear each other’s words. Little Maudie nestled at my side, and took my hand in hers. My sister clung to the rail at the other side of me.

“Don’t you think,” she said, “that we could sail right into one of the harbours in Arran? I know there is a harbour at Brodick, which is just opposite us.”

“We had better keep away from it altogether,” I said. “We should be sure to be wrecked if we got near the coast; and it is just as bad to be wrecked there as in the open sea.”

“Where are we going?” she cried.

“Anywhere the wind takes us,” I answered; “it is our only chance. Don’t cry, Maudie; we’ll get back all right when the storm is over.” I tried to comfort them, for they were both in tears; and, indeed, I could hardly keep my sobs down myself, for I was a very little fellow to be placed in such a position.

As the storm came down on us it became so dark that we could hardly see the island in front of us, and the dark line of the Bute coast. We flew through the water at a tremendous pace, skimming over the great seething waves, while the wind howled and screamed through our rigging as though the whole air was full of pursuing fiends intent upon our destruction. The two girls cowered, shivering with terror, at the bottom of the boat, while I endeavoured to comfort them as well as I could, and to keep our craft before the wind. As the evening drew in and we increased our distance from the shore; the gale grew in power. The great dark waves towered high above our mast-head, so that when we lay in the trough of the sea, we saw nothing but the sombre liquid walls in front and behind us. Then we would sweep up the black slope, till from the summit we could see a dreary prospect of raging waters around us, and then we would sink down, down into the valley upon the other side. It was only the extreme lightness and buoyancy of our little craft which saved her from instant destruction. A dozen times a gigantic billow would curl over our heads, as though it were about to break over us, but each time the gallant boat rose triumphantly over it, shaking herself after each collision with the waters as a seabird might trim her feathers.

Never shall I forget the horrors of that night! As the darkness settled down upon us, we saw the loom of a great rock some little distance from us, and we knew that we were passing Ailsa Craig. In one sense it was a relief to us to know that it was behind us, because there was now no land which we need fear, but only the great expanse of the Irish Sea. In the short intervals when the haze lifted, we could see the twinkling lights from the Scottish lighthouses glimmering through the darkness behind us. The waves had been terrible in the daytime, but they were worse now. It was better to see them towering over us than to hear them hissing and seething far above our heads, and to be able to make out nothing except the occasional gleam of a line of foam. Once, and once only, the moon disentangled itself from the thick hurrying clouds which obscured its face. Then we caught a glimpse of a great wilderness of foaming, tossing waters, but the dark scud drifted over the sky, and the silvery light faded away until all was gloom once more.

What a long weary night it was! Cold and hungry, and shivering with terror, the three of us clung together, peering out into the darkness and praying as none of us had ever prayed before. During all the long hours we still tore through the waters to the south and west, for the wind was now blowing from the north-east. As the day dawned, grey and cheerless, we saw the rugged coast of Ireland lining the whole western horizon. And now it was, in the first dim light of dawn, that our great misfortune occurred to us. Whether it was the result of the long-continued strain, or whether some gust of particular violence had caught the sail, we have never known, but suddenly there was a sharp cracking, rending noise, and next moment our mast was trailing over the side, with the rigging and the sails flapping on the surface of the water. At the same instant, our momentum being checked, a great sea broke over the boat and nearly swamped us. Fortunately the blow was so great, that it drove our boat round so that her head came to the seas once more. I bailed frantically with my cap, for she was half full of water, and I knew a little more would sink her, but as fast as I threw the water out, more came surging in. It was at this moment, when all seemed lost to us, that I heard my sister give a joyful cry, and looking up, saw a large steam launch ploughing its way towards us through the storm. Then the tears which I had restrained so long came to my relief, and I broke down completely in the reaction which came upon us, when we knew that we were saved.

It was no easy matter for our preservers to rescue us, for close contact between the two little craft was dangerous to both. A rope was thrown to us, however, and willing hands at the other end drew us one after the other to a place of safety. Maudie had fainted, and my sister and I were so weakened by cold and fatigue, that we were carried helpless to the cabin of the launch, where we were given some hot soup, after which we fell asleep, in spite of the rolling and tossing of the little vessel.

How long we slept I have no idea, but when we woke it appeared to be considerably past mid-day. My sister and Maudie were in the bunk opposite, and I could see that they were still sleeping. A tall, dark-bearded man was stooping over a chart which was pinned down to the table, measuring out distances with a pair of compasses. When I moved he glanced up and saw that I was awake.

“Well, mate,” he said cheerily, “how are you now?”

“All right,” I said; “thanks to you.”

“It was touch and go,” he remarked. “She foundered within five minutes of your coming aboard. Have you any idea where you are now?”

“No,” I said.

“You’re just off the Isle of Man. We’re going to land you there on the west coast, where no one is likely to see us. We’ve had to go out of our course to do it, and I should have preferred to have taken you on to France, but the master thinks you should be sent home as soon as possible.”

“Why don’t you want to be seen?” I asked, leaning on my elbow.

“Never mind,” he said; “we don’t—and that’s enough. Besides, you and these girls must keep quiet about us when you land. You must say that a fishing-boat saved you.’

“All right,” I said. I was much surprised at the earnestness with which the man made the request. What sort of vessel was this that we had got aboard of? A smuggler, perhaps, certainly something illegal, or else why this anxiety not to be seen? Yet they had been kind and good to us, so whatever they might be, it was not for us to expose them. As I lay speculating upon the point I heard a sudden bustle upon deck, and a head looked down the hatchway.

“There’s a vessel ahead of us that looks like a gun-boat,” it said.

The captain—for such I presumed the dark-haired man to be—dropped his compasses, and rushed upon deck. A moment later he came down, evidently much excited.

“Come on,” he said; “we must get rid of you at once.” He woke the girls up, and the three of us were hurried to the side and into a boat, which was manned by a couple of sailors. The hilly coast of the island was not more than a hundred or two yards away. As I passed into the boat, a middle-aged man, in dark clothes and a grey overcoat, laid his hand upon my shoulder.

“Remember,” he said—”silence! You might do much harm!”

“Not a word,” I answered.

He waved an adieu to us as our oarsmen bent to their oars, and in a few minutes we found our feet once more upon dry land. The boat pulled rapidly back, and then we saw the launch shoot away southward, evidently to avoid a large ship which was steaming down in the distance. When we looked again she was a mere dot on the waters, and from that day to this we have never seen or heard anything of our deliverers.

I fortunately had money enough in my pocket to send a telegram to my father, and then we put up at a hotel at Douglas, until he came himself to fetch us away. Fear and suspense had whitened his hair; but he was repaid for all when he saw us once more, and clasped us in his arms. He even forgot, in his delight, to scold us for the piece of treachery which had originated our misfortunes; and not the least hearty greeting which we received upon our return to the banks of the Clyde was from old Jock himself, who had quite forgiven us our desertion.

And who were our deliverers? That is a somewhat difficult question to answer, and yet I have an idea of their identity. Within a few days of our return, all England was ringing with the fact that Stephens, the famous Fenian head-centre, had made good his escape to the Continent. It may be that I am weaving a romance out of very commonplace material; but it has often seemed to me that if that gun-boat had overtaken that launch, it is quite possible that the said Mr. Stephens might never have put in an appearance upon the friendly shores of France. Be his politics what they may, if our deliverer really was Mr. Stephens, he was a good friend to us in our need, and we often look back with gratitude to our short acquaintance with the passenger in the grey coat.