David Livingstone : African Development – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XIV : The New Era by John Lord

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XIV : The New Era

Richard Wagner : Modern Music

John Ruskin : Modern Art

Herbert Spencer : The Evolutionary Philosophy

Charles Darwin : His Place in Modern Science

John Ericsson : Navies of War and Commerce

Li Hung Chang : The Far East

David Livingstone : African Development

Sir Austen Henry Layard : Modern Archaeology

Michael Faraday : Electricity and Magnetism

Rudolf Virchow : Medicine and Surgery

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XIV : The New Era

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Difficulties of exploration in the “Dark Continent”

Livingstone’s belief that “there was good in Africa,” and that it was worth reclaiming.

His early journeyings kindled the great African movement.

Youthful career and studies, marriage, etc.

Contact with the natives; wins his way by kindness.

Sublime faith in the future of Africa.

Progress in the heart of the continent since his day.

Interest of his second and third journeyings (1853-56).

Visits to Britain, reception, and personal characteristics.

Later discoveries and journeyings (1858-1864, 1866-1873).

Death at Chitambo (Ilala) Lake Bangweolo, May 1, 1873.

General accuracy of his geographical records; his work, as a whole, stands the test of time.

Downfall of the African slave-trade, the “open sore of the world”.

Remarkable achievements of later explorers and surveyors.

The work of Burton, Junker, Speke, and Stanley.

Father Schynse’s chart.

Surveys of Commander Whitehouse.

Missionary maps of the Congo Free State and basin.

Other areas besides tropical Africa made known and opened up.

Pygmy tribes and cannibalism in the Congo basin.

Human sacrifices now prohibited and punishable with death.

Railway and steamboat development, and partition of the continent.

South Africa: the gold and diamond mines and natural resources.

Future philanthropic work.

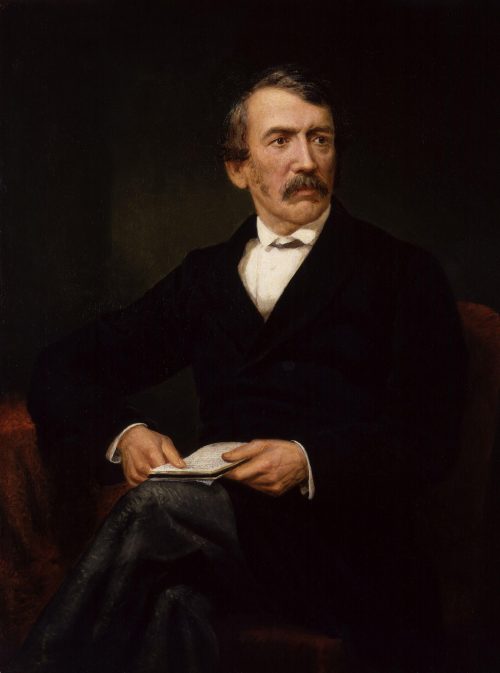

David Livingstone : African Development

By Cyrus C. Adams.

1813-1873.

Africa is the most ancient and the most recent conquest of the human race. As far as the light of history can be projected into the past, we see Egypt among the first and foremost on the threshold of civilization. The continent discovered last and opened last to the enterprises of the world is still Africa. Why is it that we see there both the dawn of civilization and the tardiest development of human progress?

The reasons are not far to seek. The physical conformation of no other continent is so unfavorable for exploration and development. Africa’s straight coastlines, affording little shelter to the primitive ships of early mariners, repelled the enterprising Phoenicians and other seafarers in their eager search for new lands worth colonizing. Nor was it easy for explorers to penetrate into the interior. In its surface Africa has been compared to an inverted saucer,–the high plateaus occupying most of the interior descending to the sea by short, abrupt, and steep slopes, so that the wide and peaceful rivers of the plateaus are lashed into foam as they approach the ocean by many series of rapids and cataracts.

In all the other continents rivers have been the lines of least resistance to the advance of man. Civilization has developed first along the great rivers. The valleys were first settled, and up these valleys man carried his industries and commerce far inland. Thus the Euphrates and Tigris of Mesopotamia, the Ganges and Indus of India, and the Hoang and Yangtse of China, were the creators of history; but this is true in Africa only of the Nile. All the other rivers have been impediments instead of helpful factors in the formidable task of exploration and development.

The trying climate, also, gave Africa odious repute and delayed for centuries the study and utilization of the continent. When the British expedition under Captain Tuckey attempted to ascend the Congo, in 1816, to see if it were really the lower part of the Niger River, as had been conjectured, nearly all of its members perished miserably among the rapids less than two hundred miles from the sea. Such tragedies as this paralyzed enterprise in Africa until white men learned that the climate was not so deadly, after all, if they adhered to the manner of life, the hygienic rules, that should be observed in that tropical expanse.

In all the other continents, also, explorers have had the advantage of domestic animals to carry their food and camp equipment; but in large parts of tropical Africa the horse, ox, and mule cannot live. The bite of the little tsetse fly kills them. Its sting is hardly so annoying as that of the mosquito, but near the base of its proboscis is a little bag containing the fatal poison. Camels have been loaded near Zanzibar for the journey to Tanganyika, but they did not live to reach the great lake. The “ship of the desert” can never be utilized in the humid regions of tropical Africa.

The elephant is found from sea to sea, but he has not proved to be so amenable to domestication as his Asian brother. He may yet be reduced to useful servitude. The efforts in this direction in the German and French colonies are somewhat encouraging, though in 1901 only six elephants had thus far been broken to work and were daily used as beasts of burden. Explorers of tropical Africa have always been compelled to rely upon human porterage, the most expensive and unsatisfactory form of transportation, with the result that nearly all the great lines of exploration have been extended through the continent at enormous cost.

So most other parts of the world were occupied, colonized, civilized, before Africa was explored. A continent one-fourth larger than our own was for centuries neglected and despised. “Nothing good can come out of Africa” became proverbial. Seventy years ago Africa, away from the coasts and the Nile, was almost a blank upon our maps, save for fanciful details that are ludicrously grotesque in the light of our present knowledge (1902).

Then dawned the era of David Livingstone. Sixty-two years ago this humble Scotchman went to South Africa as a missionary. It was not long before he became imbued with the idea that missionary service could not be projected on broad, economic, and effective lines till the field was known. The explorer, he said, must precede the teacher and the merchant. We can work best for Christianity and civilization after we learn what the people are and know the nature of their environment. This was the thought that took him into the unknown; that inspired him with unflagging courage and zeal throughout twenty years of weary plodding in the African wilderness among hundreds of tribes who never before had seen a white man. And all the years he was studying the country and winning the love of its people, his faith in Africa, in its abounding resources worth the world’s seeking, in the capacity of its people for development, steadily grew till it became the all-pervading impulse of his life. Livingstone’s faith converted the world to the belief that, after all, there was good in Africa.

“I shall never forget,” said Stanley, one day in New York, “the time when I stood with Livingstone on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, and he raised his trembling hand above his head, leaned towards me as he looked me in the eye, and said in a voice broken with emotion: ‘The day is coming when the whole world will know that Africa is worth reclaiming, and that its people may be brought out of barbarism. The world needs Africa; and teachers, merchants, railroads, and every influence of civilization will be spread through this continent to fit it for the place in human interests that belongs to it.’ I thought then that Livingstone was an enthusiast and a visionary; but long ago I learned to believe that every word he said was true.”

Europe and America were thrilled by the simple narrative of those twenty-two thousand miles of wanderings that brought into the light of day millions of human beings who had been as much unknown to us as though they inhabited Mars. Livingstone did not live to know it, but it was he who kindled the great African Movement,–an outburst of zeal for geographic discovery and economic development such as was never seen before.

Thirteen years ago (1889) a Frenchman named De Bissy completed the largest map yet made of Africa. In the preparation of this great work, which occupied much of his time for eight years, he used as his sources of information nearly eighteen hundred route and other maps, nearly all of which were the result of the work of explorers in the preceding quarter of a century. All that we know of the geography of over three-fourths of Africa is the work of the past half-century since Livingstone made his first journey in 1849; and we know far more of inner Africa to-day than was known of inner North America three hundred years after Columbus discovered the western world. A little over a century ago, our great-grandfathers were reading in their school geographies that North America had no conspicuous mountains except the Alleghanies; and these mountains and the Andes of South America were believed to be one and the same chain, interrupted by the Gulf of Mexico. Many men not yet bent with years can remember when the interior of Africa was a white space on the maps; but it is not possible to-day to make such a geographical blunder as we have mentioned, about any part of Africa.

It is because of the work he did in those twenty years, sowing all the while the seeds from which sprang the great African Movement, that “the gentle master of African exploration” is acclaimed to-day as one of the world’s great men, and that his body rests in Westminster Abbey among the illustrious dead of Britain.

The son of a worthy weaver in Blantyre, Scotland, Livingstone’s early life was that of a poor boy, working in a spinning-mill, quiet, sober, affectionate, and faithful in every relation of life. Moved at last by the thirst for knowledge that has distinguished many a humble Scotch boy, he entered the University at Glasgow, studying during the winter months and spending the summers at his trade in the factory, fitting himself all the while for the conquests he little dreamed he was to achieve over difficulties almost insurmountable. A classmate spoke of him as a pale, thin, retiring young man, but frank and most kind-hearted, ready for any good and useful work, even for chopping the University fuel and grinding wheat for the bread. In 1838, when he was twenty-five years old, he went to London to be examined as a candidate for the African missionary service. Two years later he was sent to South Africa, where for eight or nine years he labored among the natives earnestly and unostentatiously north of the place now famous as the site of the Kimberley diamond mines. It was here that he became intimately acquainted with the celebrated missionary, Robert Moffatt, whose daughter he married. His devoted wife accompanied him in some of his later travels, but long before he finished his work her body was laid to rest under the shade of a tree that for years was pointed out to all visitors to the Lower Zambesi.

In 1849, began the series of explorations that continued till his death. “The end of geographical discovery is the beginning of missionary enterprise,” he wrote. Burning with zeal to reveal Africa to the world, Livingstone never forgot the main aim of his life,–to open ways for the planting of mission stations among all the scores of tribes he visited. “I hope God will in mercy permit me to establish the Gospel somewhere in this region,” he wrote from the land of the Barotse, on the Upper Zambesi. Does he now look down from his eternal home upon that very land whose churches and schools are the fruition of the labors of French Protestants; whose king, in London to attend the coronation of Edward VII., said he wanted more teachers and more men to train his people to build houses and work iron? He prayed that he might live to see “the double influence of the spirit of commerce and Christianity employed to stay the bitter fountain of African misery.” The glowing zeal of the Christian philanthropist and the untiring ardor of the born explorer were perfectly blended in the spirit of the great pioneer of modern African discovery.

Livingstone’s routes through Africa would extend about seven times between New York City and San Francisco; and in his almost endless marches over plain, through jungle, across mountains and wide rivers, the natives met him almost without exception in a generous and hospitable spirit. Love was the secret of his success. He won his way by kindness. Give the barbarous African time to see that you wish him well, that you would do him good in ways he knows are helpful, and his affection is evoked.

It was said that the British could never establish their rule over the great Wabemba tribe, southwest of Tanganyika, without a military campaign. In 1894, two humble Catholic fathers entered Lobemba, walked straight to the chief town, and were told that if they did not leave the country in one day they would be killed. As the stern message was delivered, they saw an old woman on the ground in great pain from a severe wound. The news soon spread that these unwelcome strangers had washed and dressed the wound, and made the old woman comfortable. “These people love men,” was the word that passed from lip to lip, as the sick and suffering came out from the town to be treated, while thousands of natives looked on. At nightfall the white men were told they might remain another day; they ministered for eleven days to those who needed help, and were then invited to remain the rest of their lives. The mission stations of the White Fathers are to-day scattered all over Lobemba; the country is open in every corner to the whites, and in 1899 British rule was established. The victory was won, not with guns, but by gentle, helpful kindness.

Livingstone never believed that the sympathies of our common humanity are extinct even in the bosom of a savage. Enfolded in the panoply of Christian kindness, he passed unscathed among the most warlike tribes. No memory of wrong or pain rankled in the heart of any man, woman, or child he ever met. He is known to-day as “the good old man” wherever his path led him in those twenty years.

When explorers began to study the healthful highlands of the Akikuyu tribe in East Africa a few years ago, the natives rushed to arms. “Keep away from us,” they said. “One of your white men came through the land, stealing food from our gardens, and killing all who said he ought to pay us for our vegetables. We want nothing to do with thieves and murderers like you.”

But no vengeance fell on the head of any white traveller who ever followed in the footsteps of Livingstone. Those explorers have achieved most who adhered to his example of unfailing kindness, mercy, and justice. The brutal German, whose crimes made the Akikuyu hostile to all whites, marked his path with blood from the Indian Ocean to Victoria Nyanza. Serpa Pinto, renowned for the scientific value of his work, aroused condemnation and disgust because he fought his way through many tribes, among whom Livingstone and Arnot had wandered almost alone and in perfect safety. Fortunately, there have not been many explorers militant. The brilliant discoveries of Grenfell, Delcommune, Lemaire, and others, who are in the first rank of African pioneers, were made without harming a native.

Let us glance at a few of Livingstone’s discoveries and form our own conclusions as to whether his sublime faith in the future of Africa has thus far been justified by events. In the depths of the wilderness he discovered the large lake, Mweru, through which the Upper Congo flows. Though white influences have reached that remote region only within the past two or three years, a little steamboat now plies those waters. A photograph of Mpweto, one of the white settlements on the lake, shows the commodious quarters of the Europeans, two long lines of cabins in which the native workmen live, and well-tilled gardens extending for a half-mile along the shore. Livingstone brought to light the coal fields of the Zambesi, the only coal yet known in tropical Africa. While these lines are being written, the British of Rhodesia are preparing to open mines along these deposits. He told the world of the Victoria Falls of the Zambesi, the largest known, a mile wide and twice as high as Niagara. The installation of an electrical plant at this great source of power is now in progress, and it is hoped within three years to transmit electrically all the power required to work the large copper mines in the north, the coal fields in the east, and to move trains on the Cape to Cairo Railroad for a distance of three hundred miles. The recent improvements in long-distance transmission of power encourages the belief that the Victoria Falls may some day possess large industrial utility for a wide region around them. Coffee plantations on the hills overlooking the long expanse of Nyassa, the splendid freshwater sea which Livingstone revealed in its setting of mountains, are selling their superior product in London at a high price. The town of Blantyre, among the Nyassa highlands which Livingstone first described, has a newspaper, telegraphic and cable communication with all the world, and industrial schools in which the manual arts are taught to hundreds of natives. Here is the large brick church, now famous, built by native craftsmen, who before Livingstone’s time had never seen a white man, and lived in a state of barbarism; an edifice that would adorn the suburbs of any American city, and of which the explorer, Joseph Thomson, said: “It is the most wonderful sight I have seen in Africa.” The natives made the brick, burned the lime, sawed and hewed the timbers, and erected the building to the driving of the last nail. They had the capacity, and it was evoked by the genius of one of the most remarkable men in Africa, Missionary Scott of Blantyre. Steamboats are afloat on five of the six important seas of the great lake region of Central Africa; on two of the three which Livingstone discovered. Only a beginning has been made, for the field stretches from ocean to ocean; but the man who, in 1873–the year of Livingstone’s death,–should have predicted one-half of the achievement of the present generation would have been laughed at as a crack-brained visionary.

Even the surface of Africa is changing, and the truth of Livingstone is not always the truth of to-day. In his first journey, in which he braved the perils of the South African thirst lands, he reached the broad and placid expanse of Lake Ngami, covering an area of three hundred square miles. In the gradual desiccation of that region, the lake has now entirely disappeared. Its place is wholly occupied by a partly marshy plain covered with reeds, and no vestige of water surface is to be seen. He found the little Lake Dilolo so exactly balanced on a flat plain between two great river systems that one stream from the lake flowed north to the Congo and another south to the Zambesi; but for years past there has been no connection between the lake and the Congo. He sought in vain, like many explorers after him, for the outlet to Lake Tanganyika. The mystery was not solved till, more than twenty years after, Burton discovered the lake; the solution came when the explorer Thomson and Missionary Hore found the waters of Tanganyika pouring in a perfect torrent down the valley of the Lukuga to the Congo. The explanation of the strange phenomenon is that for a series of years the evaporation exceeds the water receipts, the level of the lake steadily falls, and the valley of the Lukuga becomes choked with grass; then a period follows when the water receipts exceed the evaporation, and the waters rise, burst through the barriers of vegetation in the Lukuga, and are carried to the Congo once more.

It was his second and third journeys that established Livingstone’s fame as a great explorer. In those journeys (1853-56) his routes were from the Upper Zambesi to Loanda in Portuguese West Africa, and then from Loanda to the mouth of the Zambesi, nearly twelve thousand miles of travel. The third journey was the first crossing of the continent; and while traversing the wide savannas of the uplands and revealing the Zambesi, the fourth largest river of Africa, from source to delta, he was able to verify one of the most brilliant generalizations ever made by a geologist. Sir Roderick Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society, in 1852, deducing his conclusions from the very fragmentary and imperfect knowledge of Africa then extant, evolved his striking hypothesis as to the physical conformation of the continent, which has been briefly mentioned above and is the accepted fact of to-day. Livingstone was able to prove the accuracy of this hypothesis, and he dedicated his “Missionary Travels” to its distinguished author.

The Makalolo chief, Sekeletu, on the Zambesi River, supplied Livingstone with men, ivory, and trading commissions, that helped the humble and unknown white man, lacking all financial resources except his slender salary, to make the two great journeys which kindled the world’s interest and led to the wonderful achievements of our generation. In this noteworthy incident we see the human agencies through which Africa will attain the full stature allotted to her. The Caucasian and the Negro each has his onerous part in the work of bringing the civilized world and Africa into touch and accord.

When Livingstone went home, after his third journey, his fellow-countrymen crowded to see and hear the explorer, who had added more facts to geographical knowledge than any other man of his time. They saw a person of middle age, plainly and rather carelessly dressed, whose deep-furrowed and well-tanned face indicated a man of quick and keen discernment, strong impulses, inflexible resolution, and habitual self-command. They heard a speaker whose command of his mother tongue was imperfect, and who apologized for his broken, hesitating speech by saying that he had not spoken the English language for nearly sixteen years. In no public place did he ever allude to his personal sufferings, though fever had brought him to death’s door and the years had been crowded with the most harrowing cares. The work he had done and would carry on to the end, the new Africa he alone could describe, the faith that had grown and strengthened in every week of his long pilgrimage that the world needed Africa, its resources and peoples, were the burden of every utterance. The great London meeting where he first appeared took practical measures to support him in the work he had begun unaided; and one of the resolutions adopted, declaring that “the important discoveries of Dr. Livingstone will tend hereafter greatly to advance the interest of civilization, commerce, and freedom among the numerous tribes and nations of that vast continent,” was prophetic of all the best fruits of the colossal work that has been done to the present time.

During his two years at home, Livingstone wrote his “Missionary Travels.” He returned to England once more (1864-65), when he published “A Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi,” and in 1866 went back to Africa to resume the explorations which ended only with his death. Between 1849 and 1873 he was four years in Europe and twenty years in the field, eating native food, sleeping in straw huts (in one of which he died), lost to view for many years at a time because he had no means of communication with the coasts. It was this fact that led to Stanley’s successful search for Livingstone in 1871. Perhaps no other explorer ever gave so many years to continuous field-work. In this respect he far surpassed the record of any other of the African pioneers.

The discoveries in his last journeys, covering the periods from 1858 to 1864, and from 1866 to 1873, were as brilliant and fruitful as his earlier work, but not so astonishing, because his first years were given to revealing the broader aspects of Africa and its tribes, while his later labors were devoted to more detailed research in a smaller field. This region, about as large as Mexico and Central America, extends north and south, from Tanganyika to the Zambesi, and covers the wide region of the Congo sources between Nyassa and Lake Bangweolo. The greatest results were the discovery of Lake Nyassa and the Shire River, now the water route into East Central Africa; Lakes Bangweolo and Mwero; and the mapping of the eastern part of the sources of the Upper Congo, which Livingstone believed to the day of his death were the ultimate fountains of the Nile. Livingstone’s “Last Journeys” was published from the manuscript which his faithful servants brought to the seacoast with the mortal remains of their gentle master.

Not far from the south coast of Bangweolo stands a wooden construction to which is affixed a bronze tablet bearing the simple inscription, “Livingstone died here. Ilala, May 1, 1873.” It has taken the place of the tree under which he died, and where his heart, which had been so true to Africa, was buried. As the tree was nearly dead, the section bearing the rude inscription cut by one of his servants was carefully removed and is now in London.

Livingstone’s geographical delineations were remarkably accurate, considering the inadequate surveying instruments with which he worked. Dr. Ravenstein, one of the greatest authorities on African cartography, has said: “I should be loath to reject Livingstone’s work simply because the ground which he was the first to explore has since his death been gone over by another explorer.” It would be marvellous, however, if in the course of twenty years of exploration he had not made some blunders. His map of Lake Bangweolo, for example, was very inaccurate. The Lokinga Mountains, which he mapped to the south of the lake, have not been found by later explorers. These imperfections resulted from the fact that his map of Bangweolo and its neighborhood was largely based upon native information. He knew that his map was inadequate, and as soon as he was able to travel he returned to Bangweolo to complete his survey. He was making straight for the true outlet of the lake, and was within thirty-five miles of it when one morning his servants found him in his lowly straw hut, dead on his knees. If Livingstone had lived a few weeks longer and been able to travel, he and not Giraud would have given us the true map of Bangweolo.

As a whole, Livingstone’s work in geography, anthropology, and natural history, stands the test of time. No river in Africa has yet been laid down with greater accuracy than the Zambesi as delineated by this explorer.

The success of Livingstone was both brilliant and unsullied. The apostle and the pioneer of Africa, he went on his way without fear, without egotism, without desire of reward. He proved that the white man may travel safely through many years in Africa. He observed richness of soil and abundance of natural products, the guarantees of commerce. He foretold the truth that the African tribes would be brought into the community of nations. The logical result of the work he began and carried so far was the downfall of the African slave-trade, which he denounced as “the open sore of the world.” What eulogy is too great for such a work and such a man?

In 1898, twenty-one journeys had been made by explorers from sea to sea. Livingstone completed the first journey, from Loanda to the mouth of the Zambesi, in one year, seven months, and twenty-two days. Nineteen years elapsed before Central Africa was crossed again, when Cameron gave two years and nearly eight months to the journey. It took Stanley two years and eight months to cross Africa, when he solved the great mystery, the course of the Congo; and when he went to the relief of Emin Pasha, in 1887, he was almost exactly the same time on the road. When Trivier crossed from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, in 1888-89, in nine days less than a year, the event was held as a remarkably rapid performance. A little later the journey was made by several travellers in from twelve to fifteen months. In 1898, the Englishman, Mr. Lloyd, crossed from Lake Victoria to the mouth of the Congo in three months, about thirteen hundred miles of the journey being by Congo steamboat and railroad. In 1902, the journey from the Indian Ocean to Lake Victoria is made by rail in two and one-half days,–a journey that occupied Speke for nine, and Stanley for eight months. With the present facilities, the continent may be crossed by way of the lake region and the Congo in about three months. The era of long and weary foot-marches has nearly ended; now succeeds travel by steam.

No influence has been so potent in improving the art of the explorer, or in raising the standard of the work required of him, as the enormous interest that for thirty years past has centred in African exploration. The larger part of the best achievements of the explorers of the present generation in scientific investigation, and in an approach to scientific map-making, are found in tropical Africa. Many of the hundreds of the route surveys are not unworthy to be compared with those of Pogge and Wissmann, when they laid down on their map every cultural and topographic feature for two miles on both sides of their route, from Angola to the Upper Congo. The extreme care with which some of the best explorers have performed their tasks is illustrated by the remarkable achievement of the late Dr. Junker along the Mobangi River. After years of service, his scientific equipment had become practically worthless. He started on his four-hundred-mile journey down the river through the jungle, with absolutely no instrument except a compass to aid him in determining his positions. Endeavoring, by the most scrupulous care, to make up as far as possible for his lack of scientific outfit, he trudged through the grass, compass in hand, counting every step. Every fifteen minutes he jotted in his notebook the distance and the mean direction travelled. At night he used these accumulated data to lay down on his route map the journey of the day. For many weeks he kept up this trying routine till he reached his furthest west, and again till he had returned to his starting-point, whose latitude and longitude he had previously determined. When he returned to Europe, Dr. Hassenstein and he made a map from the data Junker had collected, and fixed the position of his furthest west. This position was found later by the astronomical observations of Lieutenant Le Marinel to be less than two miles out of the way.

One of the latest to win a large prize in African discovery is Dr. A. Donaldson Smith, a young physician of Philadelphia, in the northeastern region known as Somaliland and Gallaland. His method may be mentioned here as an illustration of the kind of work that geographers now require. Before he began his explorations, he took a thorough course in the use of surveying instruments and the methods of accurately laying down his positions and making a route map. Many a cartographer, burning with desire to draw a good map of a newly explored region, has been driven to despair by the inadequacy of the route surveys in his hands. Not a few of these surveys have been unworthy of reproduction in the books of the explorers who made them, and the best that could be done was to generalize their information on maps of comparatively small scale. But Donaldson Smith’s route-maps appear in his book on the comparatively large scale of 1:1,000,000 (about sixteen statute miles to the inch), and they are worthy of that treatment, for his surveys and observations for geographical positions were recorded in such a way that their value might be easily ascertained by any one familiar with such computations. His route-maps have been found to be admirable map-making material; thus, he has not only traversed a new region of great extent, but has given in his map ample materials which may be employed by any atlas-maker in the production of good maps of all the territory that came under his observation. When Sir Clements Markham presented to Dr. Smith the Patrons’ Medal of the Royal Geographical Society, he said: “You have not, like an ordinary explorer, made a common route survey, but you have made a scientific survey, a triangulation frequently checked by astronomical observations with theodolite and chronometer.”

Most African explorers have been painstaking, conscientious workers, eager in their quest for the truth, desirous to report nothing but the truth, and treating the lowly and ignorant they have met as men, with sensibilities like their own, capable of gratitude for a kindness and keenly sensitive to an outrage. The world has recognized and applauded such heroes of discovery,–the men who faced hardship and peril, enduring and sacrificing much that knowledge might grow; who had to conquer not only unkind Nature, but to overcome the ignorant violence of man. And not a few of the leaders in this work have carried it out with a degree of tactfulness, humanity, gentleness, and kindliness of spirit amounting to genius. Some of them spent months in disguise, collecting facts of the highest scientific value among fanatical Mohammedans who would have killed them if they had known their secret. Such men were Burton in Harrar, Dr. Lenz in Timbuctoo, and De Foucauld and Harris in Morocco, who, in stained skins and borrowed costumes, personated merchants and devotees and doctors and Jews; and most of whom have enriched the literature of discovery with valuable books. Men also such as Dr. Junker, who, rich as he was, left his home to spend eight years alone among the savages of the Welle Makua basin in Central Africa, living on their food and in their huts that he might minutely study the people in their country; or Grenfell, who has travelled far more widely in the Congo basin than Stanley or any of his followers except Delcommune, and revealed to the world more river systems and unknown peoples than they, and who, in his long career as an explorer, never fired a shot upon a native, though his life was often threatened. These men, and others like them, have exemplified the manysidedness of human resources against a great variety of peril and obstacle, as no other explorers in any other part of the world have had an opportunity to do in equal measure. Their work, with its environment of almost overwhelming difficulty, should be known to our youth as most forceful illustrations of what good men may dare and do in good causes and in a worthy manner.

There have been some exceptions to this rule. A few men have been less anxious to perform useful service than to figure in the newspapers and pose before their public. One day a man stood on the north shore of Victoria Nyanza, and looking south he saw land. When he returned to London he published a sensational book, in which he said it was ridiculous for Speke to assert that he had discovered a lake as large as Scotland, one of the greatest lakes in the world. “Why,” said the writer, “I have stood on the north shore of the Victoria Nyanza and looked south and seen the southern shore. Lake Victoria is only an insignificant sheet of water, after all the talk of its being second only to Lake Superior.”

What he really saw was the chain of the Sesse Islands extending far out into the lake. His book was scarcely off the press when the letters describing Stanley’s boat journeys around the shores of Victoria Nyanza began to be published in London and New York; and the foolish fellow was compelled to recall all the copies of his book that had not passed beyond his reach, and eliminate the statements that made him so ridiculous. Fortunately, there are not many explorers of this stripe.

All who watched the progress of African discovery were constantly reminded that geographical progress is usually made only by slow and painful steps. They saw an explorer emerge from the unknown with his notebooks and route maps replete with most interesting facts for the student and the cartographer. Then another explorer would enter the same region, discover facts that had escaped the notice of the pioneer, correct blunders his predecessor had made and perpetrate blunders of his own; so explorer followed explorer, each adding something to geographical knowledge, each correcting earlier misconceptions, till the total product, well sifted by critical geographers, gave the world a fair idea of the region explored; but not the best attainable idea, for scientific knowledge of a region comes only with its detailed exploration by trained observers, equipped with the best appliances for use in their special fields of research. This is the advanced stage of geographical study, which is now being reached in many parts of Africa. It was Livingstone’s task, in 1859, to inform us that there was a great Lake Nyassa. It was Rhoades’s task, in 1897-1901, to make a careful and accurate survey of its coast-lines, and to sound its depths, so that we now have an excellent idea of the conformation of the lake bottom. Between Livingstone and Rhoades came many explorers, each adding important facts to our knowledge of this great sheet of water nearly twice as large as New Jersey.

As each explorer came from the wilds, our maps were corrected to conform with the new information he supplied; and if we should examine the maps of Africa in school geographies, atlases, and wall maps, from the time of Livingstone to the present day, we should see that, as relates to nearly every part of Africa, they have been in a continual state of transition.

For years our only map of Victoria Nyanza was that which Speke made on his second journey to the lake, in 1860-62; but Speke saw the great lake only at one point on its south shore, and along its northwest and north central coasts. His map, being based very largely upon native information, was in many respects most incomplete and erroneous.

Then came Stanley’s survey of the lake, made in a boat journey around its coasts, and for years his map supplanted that of Speke. But he was not able to follow the shore-line in all its intricate details. His mapping was a great advance upon that of Speke, but it was necessarily rough and imperfect. He missed entirely the deep indentation of Baumann Gulf and the southwestern prolongation of the lake, surveyed by Father Schynse, in 1891. Stanley’s map, modified by the partial surveys of various explorers, is still our mapping of the lake; but if the reader will watch the maps for the next year or so, he will doubtless observe important changes in the contours of Victoria Nyanza; for all the maps, from Speke to those of 1902, will be placed on the shelf to serve only as the historical record of the good, honest work which a number of explorers have done. Commander Whitehouse has recently spent thirteen months surveying with infinite pains these coasts and islands. “I seem to see,” writes Stanley of this important service, “the sailor, with his small crew and his little steel boat, wandering from point to point, crossing and recrossing, going from some island to some headland, taking his bearings from that headland back again to the island, and to some point far away.”

Commander Whitehouse has made a new delineation of the entire 2,200 miles of coasts, and the results of his survey will be used in making all the maps of the lake. His map in turn will undoubtedly be replaced some day by detailed topographic surveys of the best quality, such as the British already contemplate making of that entire region.

A wall map recently in use in one of the public schools of New York City was a curious example of ignorant compilation. It exhibited the Victoria Nyanza of Speke, the Bangweolo of Livingstone, and the Upper Congo of Stanley, all obsolete for practical purposes years before this map was printed. Most of our home map-makers were very slow in availing themselves of the rich materials constantly supplied for the maps by the army of explorers in Africa. But the most alert cartographers, particularly between 1880 and 1895, could not keep their maps abreast of the news of discovery as it came to Europe. More men and energy and money were utilized in those fifteen years of African discovery than in the first century and a half of American exploration. The route or mother-maps, some covering a wide extent of country, others devoted to a small area, or a short line of travel, were going to Europe for the improvement of atlas sheets by nearly every steamer. Father Schynse’s chart of the southwest extension of Victoria Nyanza had hardly been utilized in European map-houses before it was replaced by Dr. Baumann’s more accurate survey. Mr. Wauters of Belgium withdrew his large map of the Congo Basin from the printer four times, in order to include fresh information before it was finally issued to the public.

This process is still going on, though more slowly. The mapping we see of Lake Tanganyika, one of the longest lakes in the world, has been in use for seventeen years since missionary Hore made his boat journey of one thousand miles around its coasts, but the new map of the Moore expedition now being introduced gives the main axis of the lake a more northeast and southwest direction. The Hore map has met the fate that usually overtakes the early surveys of every region. It rendered good service as long as it was the best map; but the Moore expedition had first-rate appliances for computing longitudes, and as Captain Hore lacked these, it is not strange that his map has been found to be defective.

The world has been treated to many geographical surprises in the course of this incessant transformation of the map of the continent. Many of us may remember in our school geographies, the particular blackness and prominence of the Kong Mountains, extending for two hundred miles parallel with the Gulf of Guinea. They were accepted on the authority of Mungo Park, Caillié, and Bowditch, all reputable explorers who had not seen the mountains, but believed from native information that they existed. The French explorer, Binger, in 1887 sought in vain for them. Later explorers have been unable to find them. They are, in fact, a myth, and will be remembered chiefly as a conspicuous instance of geographic delusion. It had long been supposed that the navigation of the Niger River, the third largest river in Africa, was permanently impaired by the Bussa Rapids, about one hundred miles in length, where Mungo Park was wrecked and drowned. But Major Toutée, a few years ago, when assailed by hostile natives, made a safe journey with his boats through the rapids; and Captain Lenfant, in 1901, carried 500,000 pounds of supplies up the river and through the rapids to the French stations between Bussa and Timbuktu. He had a small, flat-bottomed steamboat and a number of little boats propelled by fifty black paddlers. He says that by the land route he would have required 12,000 porters, and they would have been one hundred and thirty days on the road.

It was believed that a land portage would always be necessary between the sea and the Zambesi, above the delta, till 1889, when Mr. Rankin discovered the Chinde branch of the delta, so broad and so deep that ocean vessels may ascend it and exchange freight with the river craft.

It has been found that more water pours into the ocean through the Congo’s mouth, which is six miles wide, than from all the other rivers in Africa together. It is second among the world’s rivers, and the dark detritus it carries to the Atlantic has been distinctly traced on the ocean bed for six hundred miles from the land. Some geographers still believed thirty years ago that all the waters of its upper basin might be tributary to the Nile. Map-makers have been kept very busy recording discoveries on the Congo. About one hundred explorers, some of them missionaries and many employees of the Congo Free State, have mapped the whole basin along its water-courses, and discovered the ultimate source of its main stream. Our ideas of the hydrography of this great basin have been revolutionized since Stanley, second only to Livingstone among the great African explorers, in 1877 revealed the course of the main river.

On his map, for example, he showed the southern tributaries as probably flowing nearly due north; but all except one of these rivers rise in the east and flow far to the west. When Wissmann was sent to the Upper Kassai to follow it to the Congo, he was greatly surprised to find himself floating westward week after week. When he reached the Congo a steamboat was waiting for him at Equatorville, two hundred miles further up the river, where he was expected to emerge. Schweinfurth believed the Welle Makua flowed north to Lake Chad on the edge of the Sahara; seventeen years later, after six or seven explorers had tried to solve the problem, the river was found to be the upper part of the Mobangi tributary of the Congo, larger than any rivers of Europe, excepting the Volga and Danube. While Stanley was for five years planting his stations on the Congo, he knew nothing of this great tributary, 1,500 miles long, whose mouth was hidden by a cluster of islands which his steamers repeatedly passed. Missionary Grenfell, on his little steamer, was ascending the Congo one day, when accidentally he got into the mouth of the Mobangi and went on for one hundred miles before he discovered that he had left the main river. Few explorers have unwittingly stumbled upon so rich a geographical prize.

While exploratory enterprises have been centred largely in tropical Africa, no part of the continent has been neglected. We now know that large areas of the Sahara are underlaid by waters which need only be brought to the surface to cover the desert around them with verdure; that most of the rain falling on the south slopes of the Atlas Mountains sinks into the earth to impermeable strata of rock, along which it makes its way far out into the desert; that where the surface is depressed so that these waters come near to it, there are wells for the refreshment of the camel caravans, and oases, blooming islands of green, in the sterile wastes; and that artesian wells bring inexhaustible supplies of water within reach, so that millions of date palms have been planted along the northern edge of the desert in southern Algiers and Tunis, making these regions the largest sources of the world’s supply of dates.

It has also been discovered why there are very large areas of dry or desert lands in Africa. The Sahara and the southwest of Africa are deserts because the prevailing winds, the carriers of moisture, blow towards the sea instead of away from it, and consequently are always dry. The winds from the Indian Ocean crossing the highlands of Abyssinia are wrung nearly dry while passing the mountains, and so Somaliland and the lowlands to the south of Abyssinia are parched.

It has been found that the most of South Africa stands so high above the sea that the influences of a temperate climate are projected far towards the Equator; so that many white men, women, and children are living and thriving on farms in Mashonaland, seven degrees of latitude nearer the equator than the south end of Florida. This fact will profoundly influence the development of South Africa. It is to be the home of millions of the white race, the seat of a highly civilized empire, whose business relations with the rest of the world will be to the advantage of every trading nation. The presence of these millions of toilers will vitally affect the work of developing tropical Africa which is now absorbing such enormous treasure and energy; for South Africa is to be brought by railroads to the very doors of the tropical zone.

It is hoped that such facts as these, even though very briefly stated, may convey broadly a correct impression of the magnitude of African exploration, since its revival about the time that Livingstone died. It is impossible in brief space to signalize the good work that many of the most conspicuous pioneers have done. The world rendered tardy tribute to the notable achievements of some of them. When Rebmann discovered Kilimanjaro, not far from the equator, and told of the snows that crown the loftiest of African summits, it was decided by British geographers that Rebmann’s snow was probably an imaginary aspect. The snow was there, and plenty of it, but Rebmann died before justice was done to his faithful labors. When Paul du Chaillu described the Obongo dwarfs of West Africa, his narrative was discredited; but four or five groups of dwarfs, probably numbering many thousands, are now known to be scattered from the lower border of Abyssinia to the Kalahara desert in the far south. The ancients had heard of the dwarfs, but the geographers of the eighteenth century expunged from the maps of Africa about all that the geographers of Greece and Rome, as well as those of later times, placed on them; and the nineteenth century was slow in crediting the early investigators even with statements that were wholly or approximately accurate.

A curious history is connected with the discovery of the northeastern group of pygmies, a little south of Abyssinia. No white man had ever seen them, but about fifteen years ago Dr. Henry Schlichter, of the British Museum, collected all the information which natives had given to missionaries, traders, and explorers of the existence of these little people some hundreds of miles from the sea. Sifting all this evidence, he concluded that these dwarfs really existed, and that they lived in a region which he marked on the map north of Lake Stefanie. Donaldson Smith had not heard of Schlichter’s paper, and knew nothing of these dwarfs, but he found them in 1895 in the region which Schlichter had indicated as their probable habitat.

The broadest generalization with regard to the African tribes is that which separates most of the peoples south of the Sahara Desert into two great groups,–the Negro tribes, whose habitat may be roughly indicated as extending between the Atlantic and Gallaland in East Africa, with the Sahara as their northern, and the latitude of the Cameroons as their southern, boundaries; and the Bantu tribes, occupying nearly all of Africa south of the Negroes. The distinction between these two great groups is not based upon special differences as to physical structure, mental characteristics, habits, or development, but depends solely upon philological considerations, the languages of the Negroes and the Bantus forming two distinct groups. Most of the slaves who were brought to our country were Negroes, while most of those transported to Latin America were from the Bantu tribes.

One fact that stood out above all others in the study of the African natives, was the remarkable prevalence of cannibalism in the Congo basin. In all his wanderings, Livingstone met only one cannibal tribe,–the Manyema living between Tanganyika and the Upper Congo; but though they are not found near the sources of the river, nor near its mouth, they occupy about one-half of the Congo basin. They are regarded with fear and abhorrence by all tribes not addicted to the practice. They number several millions. Instead of being the most debased of human creatures, many of them, in physical strength and courage, in their iron work, carving, weaving, and other arts, are among the most advanced of African tribes. The larger part of the natives in the service of the Congo Free State are from the cannibal tribes. The laws now impose severe penalties for acts of cannibalism, and the evil is decreasing as the influence of the state is extended over wider areas. A few isolated tribes along the Gulf of Guinea are also cannibals.

There is no doubt that the helpful influences of the Caucasian in every part of Africa so far outweigh his harmful influences that the latter are but a drop in the bucket in comparison. It is most unfortunate that a certain admixture of blundering, severity, brutality, and wickedness seems inseparable from the development of all the newer parts of the world. The demoralizing drink traffic, the scandalous injustice and cruelty of some of the agents of civilized governments, are not to be belittled or condoned. But there is also a very bright side to the story of the white occupancy of Africa.

The family of a deceased chief in Central Africa recently preserved his body unburied for fourteen months, in the hope that they might prevail upon the British Government to permit the sacrifice of women and slaves on his grave, that he might have companions of his own household in the other world. He was buried at last, without shedding a drop of blood. Human sacrifices are now punishable with death throughout a large part of barbarous Africa, and the terrible evil is being abated as fast as the influence of the European governments is extended over new regions. The practice of the arts of fetichism, a kind of chicanery, most injurious in its effects upon the superstitious natives, is now punishable throughout the Congo Free State and British Rhodesia. Arab slave-dealers no longer raid the Congo plains and forests for slaves, killing seven persons for every one they lead into captivity. Slave-raiding has been utterly wiped out in all parts of Africa, except in portions of the Sudan and other districts over which white rule has not yet been asserted. The Arabs of the Congo, who went there from East Africa solely that they might grow rich in the slave trade, are now settled quietly on their rice and banana plantations. The sale of strong drink has been restricted by international agreement to the coast regions, where the traffic has long existed, and its evils are somewhat mitigated there by the regulations now enforced. Fifty thousand Congo natives who would not carry a pound of freight for Stanley in 1880, are now in the service of the white enterprises, many of them working, not for barter goods, but for coin. Many of the missionary fields are thriving, and wonderful results have been achieved in some of them. In Uganda, where Stanley in 1875 saw King Mtesa impaling his victims, there are now ninety thousand natives professing Christianity, three hundred and twenty churches, and many thousands of children in the schools. Fifty thousand of the people can read. Between 1880 and 1882 Stanley carried three little steamboats around 235 miles of rapids to the Upper Congo. Eighty steamers are now afloat there, plying on nearly 8,000 miles of rivers, and connected with the sea by a railroad that has paid dividends from the day it was opened. At the end of 1890 there were only 5,813 miles of railroad in Africa. About 15,000 miles are now in operation, and the end of this decade is certain to see 25,000 miles of railroads. Trains are running from Cairo to Khartum, the seat of the Mahdist tyranny, in the centre of a vast region which, until recently, had been closed for many years to all the world.

These wonderful results are the fruits of the partition of Africa among the European states. With the exception of some waste regions in the Libyan desert, which no one has claimed, Morocco, Abyssinia, and Liberia, every square mile of African territory has been divided among European powers, either as colonies or as spheres of influence. The scramble of twenty years for African lands is at an end, there now being no valuable areas that are not covered by the existing agreements. It is no mere love of humanity that has impelled the European countries to divide these regions among themselves. We can scarcely realize the intensity of the struggle for existence in many of the overcrowded parts of Europe. Their factories are enormously productive, but their people will suffer for food unless they can export manufactures. The crying need for new markets, for new sources of raw material, drove these states into Africa. And we should be glad, for Africa’s sake, that they have gone there, even though the desire to make money is one of the most powerful incentives.

It is under the protective aegis of these governments that explorers are settling down in smaller areas to see what may be found between the explored water-courses, to study the continent in detail, to give to our knowledge of Africa the scientific quality now required. The greatest geographical work there in recent years is the extension of a line of stations across tropical Africa by Commander Lemaire, each position astronomically fixed by the most careful methods, constituting a base-line east and west through Africa to which the scientific mapping of a very large area will be referred.

The day of the minuter study of the whole continent has now dawned, and we are witnessing a most notable work. All the colonial powers, and the Germans most conspicuously, are studying the economic questions relating to their African possessions. The suitability of climates for colonists, the essential rules of hygiene, the development of agriculture, labor supplies, transportation and commercial facilities, and many other problems are receiving the most careful attention. Experiment stations are maintained in the colonies and colonial schools at home, to fit young men for service in the field. The Germans have already proved that cotton and tobacco are certain to become profitable export crops.

The mine-owners of the Witwatersrand, on which Johannesburg stands, have begun a movement which they hope will result in the immigration of 100,000 white laborers to the mining field. We may look for remarkable development in South Africa, whose promise is larger than that of any other part of the continent. Whatever may be said of some of the methods by which the British have enlarged their empire, their rule has blessed the barbarous peoples whose countries they have absorbed. The task of improving the few millions of blacks in South Africa, and of developing the large and in some respects wonderful resources of that region, will be greatly assisted by the incoming of hundreds of thousands of Europeans, bringing with them the arts and other blessings of civilization. The future of none of the newer parts of the world is brighter with the hope of great development than the region between the Zambesi and the Cape of Good Hope.

In order to observe intelligently the progress of South Africa in coming years, the limitations as well as the advantages of the country must be kept in view. More than half of it, including the entire western half, is deficient in rainfall and can never be the home of a dense white population. Some mining will develop on those broad, dry plains and sandy wastes; some agriculture where irrigation is possible; and great wool-growing wherever thrive the nutritious grasses on which 13,000,000 sheep, scattered over the Karroo of Cape Colony, and 4,000,000 in the little Orange Free State, were grazing before the recent war. Wool-growing will always be the greatest grazing industry, though cattle and horses are raised in large numbers, and the fine, soft hair of the Angora goat is second only to wool in export importance.

A narrow strip of fine farm lands across the south end of Africa, another along the southern border of the former Boer republics, and a large area among the highlands of Mashonaland, far towards the equator, produce nearly all the crops of the temperate zones. It is not yet certain, however, that South Africa will ever raise enough wheat for a great white population. On the northern slopes of the hills, east and northeast of Cape Town, are thousands of acres of grapes. Cape Colony is becoming one of the important wine countries; and in February and March, large quantities of grapes, peaches, nectarines, and plums are placed in cool rooms on steamships and sent fresh to British markets almost before English fruit trees are in bloom.

East of the grape region is an area peculiarly adapted for the cultivation of tobacco; and east of the tobacco district, north of the coastal belt of wheat in a region of sandy scrub, the bush country, are the ostrich farms, in the hands mainly of men of considerable capital, who supply nearly all the feathers derived from the domesticated ostrich. The plumes are sometimes worth as much as $200 a pound, the ordinary feathers bringing from $5 to $7 a pound. Natal is unique in two of its agricultural industries, being the only colony that is producing tea and important quantities of cane sugar.

But gold, widely scattered over the country on the interior plateau, exceeds in value all the other exports together. The world never saw such a development of gold mining in a small area as has occurred on the Witwatersrand, where Johannesburg stands. The Witwatersrand (White River Slope) is a slight elevation, the water parting between rivers, about one and a half miles wide and 125 miles long. On twenty-five miles of the rand, at and near Johannesburg, more gold was produced in the year before the Boer war than was yielded by any other country in the world, The other rich mining regions of the Transvaal and other parts of South Africa have been completely dwarfed by the wonderful product of the rand. The surveys in Matabeleland and Mashonaland show gold-bearing areas 5,000 square miles in extent, which as yet have practically no development. The mining companies on the rand and elsewhere are now preparing for far larger operations than ever before.

The Kimberley diamond mines, turning out more than $20,000,000 worth of rough stones a year, supply nearly all the diamonds of commerce. Two other diamond centres in the Orange River Colony have scarcely been touched, and diamonds are found on the Limpopo River and in other regions where no mining has been undertaken. The minerals of South Africa, including iron and coal, bid fair to be for many years the largest sources of wealth; and in wool, hides, mohair, fresh fruits, and some other products, South Africa may rival other parts of the world.

There are no good natural harbors except Delagoa Bay in Portuguese East Africa, but by great expenditure the harbors of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, and Durban have been adapted for great commerce. Many persons mistakenly regard Cape Town as the chief commercial centre of South Africa. It is so only in respect of the export of gold and diamonds. As it is not centrally situated for business with the interior, more of the things that South Africa sells to and buys from the rest of the world, excepting gold and diamonds, pass through Port Elizabeth than through any other port. Here is centred the largest wholesale trade.

What South Africa needs is more railroads and more white labor. Manufacturing industries on an important scale are yet to come, for as yet the white population is too sparse to develop anything but the natural products of the country.

The broad summing up of the future work in Africa is that the native will be taught to help himself. The destiny of the continent depends largely upon his development, for great parts of Africa may never be adapted to become the home of many white men. The most powerful motives, philanthropic and selfish, incite and will sustain the work of helping these millions to rise to a higher plane of humanity. This work, now well begun, is the great task which in the present century will call for all the knowledge, patience, humanity, and justice that may be brought to bear upon the problem of reclaiming Africa.

Authorities.

Livingstone’s “Missionary Travels,” “A Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi,” and “Last Journeys;” Blaikie’s “Livingstone’s Personal Life;” Stanley’s “How I found Livingstone.”

Stanley’s “Through the Dark Continent,” “The Congo and the Founding of its Free State,” “In Darkest Africa;” Schweinfurth’s “The Heart of Africa;” Burton’s “The Lake Regions of Central Africa;” Speke’s “Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile;” Thomson’s “To the Central African Lakes and Back;” Barth’s “Travels and Discoveries in Central Africa;” Theal’s “Compendium of South African History;” Greswell’s “Geography of Africa South of the Zambesi”; Noble’s “The Redemption of Africa” (A History of African Missions).

No comprehensive compendium of the history of African exploration has yet been written. Our knowledge of the geography, peoples and resources of Africa is treated with considerable detail in a number of works such as Reclus’s “Africa” (in “The Earth and Its Inhabitants”) and Sievers’s “Afrika” (German). A very large part of the exploratory enterprises in Africa have not been described in books, but only in the reports of the explorers, printed with their original maps in the publications of many geographical and missionary societies.

William Hayes Ward – Sir Austen Henry Layard : Modern Archaeology

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XIV : The New Era