Czar Nicholas : The Crimean War – Beacon Lights of History, Volume X : European Leaders by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume X : European Leaders

William IV : English Reforms

Sir Robert Peel : Political Economy

Cavour : United Italy

Czar Nicholas : The Crimean War

Louis Napoleon : The Second Empire

Prince Bismarck : The German Empire

William Ewart Gladstone : The Enfranchisement of the People

Beacon Lights of History, Volume X : European Leaders

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Origin of the Russians.

Extension of Russian conquests.

Conquests of Catherine I.

Conquests of Alexander I.

Conquests of Nicholas.

Treaty of Adrianople.

Ambition and aims of Nicholas.

His character.

Prince Mentchikof.

Lord Stratford.

Causes of the Crimean War.

England and France in alliance with Turkey.

Occupation by Russia of the Danubian provinces.

War declared.

Lord Palmerston.

Lord Aberdeen.

Lord Raglan.

Marshal Saint-Arnaud.

English and French at Varna.

Invasion of the Crimea.

Battle of Alma.

Colonel Todleben.

Siege of Sebastopol.

Battle of Balaklava.

“The Light Brigade”.

“The Heavy Brigade”.

Battle of Inkerman.

Horrors of the siege.

General disasters.

Florence Nightingale.

Sardinia joins the allies.

Assault of Sebastopol.

Death of Lord Raglan.

Treaty of Paris.

Indecisive results of the war.

The Eastern Question.

Czar Nicholas : The Crimean War

1796-1855.

For centuries before the Russian empire was consolidated by the wisdom, the enterprise, and the conquests of Peter the Great, the Russians cast longing eyes on Constantinople as the prize most precious and most coveted in their sight.

From Constantinople, the capital of the Greek empire when the Turks were a wandering and unknown Tartar tribe in the northern part of Asia, had come the religion that was embraced by the ancient czars and the Slavonic races which they ruled. To this Greek form of Christianity the Russians were devotedly attached. They were semi-barbarians, and yet bigoted Christians. In the course of centuries their priests came to possess immense power,–social and political, as well as ecclesiastical. The Patriarch of Moscow was the second personage of the empire, and the third dignitary in the Greek Church. Religious forms and dogmas bound the Russians with the Greek population of the Turkish empire in the strongest ties of sympathy and interest, even when that empire was in the height of its power. To get possession of those principalities under Turkish dominion in which the Greek faith was the prevailing religion had been the ambition of all the czars who reigned either at Moscow or at St. Petersburg. They aimed at a protectorate over the Christian subjects of the Porte in Eastern Europe; and the city where reigned the first Christian emperor of the old Roman world was not only sacred in their eyes, and had a religious prestige next to that of Jerusalem, but was looked upon as their future and certain possession,–to be obtained, however, only by bitter and sanguinary wars.

Turkey, in a religious point of view, was the certain and inflexible enemy of Russia,–so handed down in all the traditions and teachings of centuries. To erect again on the lofty dome of St. Sophia the cross, which had been torn down by Mohammedan infidels, was probably one of the strongest desires of the Russian nation; and this desire was shared in a still stronger degree by all the Russian monarchs from the time of Peter the Great, most of whom were zealous defenders of what they called the Orthodox faith. They remind us of the kings of the Middle Ages in the interest they took in ecclesiastical affairs, in their gorgeous religious ceremonials, and in their magnificent churches, which it was their pride to build. Alexander I. was, in his way, one of the most religious monarchs who ever swayed a sceptre,–more like an ancient Jewish king than a modern political sovereign.

But there was another powerful reason why the Russian czars cast their wistful glance on the old capital of the Greek emperors, and resolved sooner or later to add it to their dominions, already stretching far into the east,–and this was to get possession of the countries which bordered on the Black Sea, in order to have access to the Mediterranean. They wanted a port for the southern provinces of their empire,–St. Petersburg was not sufficient, since the Neva was frozen in the winter,–but Poland (a powerful kingdom in the seventeenth century) stood in their way; and beyond Poland were the Ukraine Cossacks and the Tartars of the Crimea. These nations it was necessary to conquer before the Muscovite banners could float on the strongholds which controlled the Euxine. It was not until after a long succession of wars that Peter the Great succeeded, by the capture of Azof, in gaining a temporary footing on the Euxine,–lost by the battle of Pruth, when the Russians were surrounded by the Turks. The reconquest of Azof was left to Peter’s successors; but the Cossacks and Tartars barred the way to the Euxine and to Constantinople. It was not until the time of Catherine II. that the Russian armies succeeded in gaining a firm footing on the Euxine by the conquest of the Crimea, which then belonged to Turkey, and was called Crim Tartary. The treaties of 1774 and 1792 gave to the Russians the privilege of navigating the Black Sea, and indirectly placed under the protectorate of Russia the territories of Moldavia and Wallachia,–provinces of Turkey, called the Danubian principalities, whose inhabitants were chiefly of the Greek faith.

Thus was Russia aggrandized during the reign of Catherine II., who not only added the Crimea to her dominions,–an achievement to which Peter the Great aspired in vain,–but dismembered Poland, and invaded Persia with her armies. “Greece, Roumelia, Thessaly, Macedonia, Montenegro, and the islands of the Archipelago swarmed with her emissaries, who preached rebellion against the hateful Crescent, and promised Russian support, Russian money, and Russian arms.” These promises however were not realized, being opposed by Austria,–then virtually ruled by Prince Kaunitz, who would not consent to the partition of Poland without the abandonment of the ambitious projects of Catherine, incited by Prince Potemkin, the most influential of her advisers and favorites. She had to renounce all idea of driving the Turks out of Turkey and founding a Greek empire ruled over by a Russian grand duke. She was forced also to abandon her Greek and Slavonic allies, and pledge herself to maintain the independence of Wallachia and Moldavia. Eight years later, in 1783, the Tartars lost their last foothold in the Crimea by means of a friendly alliance between Catherine and the Austrian emperor Joseph II., the effect of which was to make the Russians the masters of the Black Sea.

Catherine II., of German extraction, is generally regarded as the ablest female sovereign who has reigned since Semiramis, with the exception perhaps of Maria Theresa of Germany and Elizabeth of England; but she was infinitely below these princesses in moral worth,–indeed, she was stained by the grossest immoralities that can degrade a woman. She died in 1796, and her son Paul succeeded her,–a prince whom his imperial mother had excluded from all active participation in the government of the empire because of his mental imbecility, or partial insanity. A conspiracy naturally was formed against him in such unsettled times,–it was at the height of Napoleon’s victorious career,–resulting in his assassination, and his son Alexander I. reigned in his stead.

Alexander was twenty-four when, in 1801, he became the autocrat of all the Russias. His reign is familiar to all the readers of the wars of Napoleon, during which Russia settled down as one of the great Powers. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 the duchy of Warsaw, comprising four-fifths of the ancient kingdom of Poland, was assigned to Russia. During fifty years Russia had been gaining possession of new territory,–of the Crimea in 1783, of Georgia in 1785, of Bessarabia and a part of Moldavia in 1812. Alexander added to the empire several of the tribes of the Caucasus, Finland, and large territories ceded by Persia. After the fall of Napoleon, Alexander did little to increase the boundaries of his empire, confining himself, with Austria and Prussia, to the suppression of revolutionary principles in Europe, the weakening of Turkey, and the extension of Russian influence in Persia. In the internal government of his empire he introduced many salutary changes, especially in the early part of his reign; but after Napoleon’s final defeat, his views gradually changed. The burdens of absolute government, disappointments, the alienation of friends, and the bitter experiences which all sovereigns must learn soured his temper, which was naturally amiable, and made him a prey to terror and despondency. No longer was he the frank, generous, chivalrous, and magnanimous prince who had called out general admiration, but a disappointed, suspicious, terrified, and prematurely old man, flying from one part of his dominions to another, as if to avoid the assassin’s dagger. He died in 1825, and was succeeded by his brother,–the Grand Duke Nicholas.

The throne, on the principles of legitimacy, properly belonged to his elder brother,–the Grand Duke Constantine. Whether this prince shrank from the burdens of governing a vast empire, or felt an incapacity for its duties, or preferred the post he occupied as Viceroy of Poland or the pleasures of domestic life with a wife to whom he was devoted, it is not clear; it is only certain that he had in the lifetime of the late emperor voluntarily renounced his claim to the throne, and Alexander had left a will appointing Nicholas as his successor.

Nicholas had scarcely been crowned (1826) when war broke out between Russia and Persia; and this was followed by war with Turkey, consequent upon the Greek revolution. Silistria, a great fortress in Bulgaria, fell into the hands of the Russians, who pushed their way across the Balkan mountains and occupied Adrianople. In the meantime General Paskievitch followed up his brilliant successes in the Asiatic provinces of the Sultan’s dominions by the capture of Erzeroum, and advanced to Trebizond. The peace of Adrianople, in September, 1829, checked his farther advances. This famous treaty secured to the Russians extensive territories on the Black Sea, together with its navigation by Russian vessels, and the free passage of Russian ships through the Dardanelles and Bosphorus to the Mediterranean. In addition, a large war indemnity was granted by Turkey, and the occupancy of Moldavia, Wallachia, and Silistria until the indemnity should be paid. Moreover, it was agreed that the hospodars of the principalities should be elected for life, to rule without molestation from the Porte upon paying a trilling tribute. A still greater advantage was gained by Russia in the surrender by Turkey of everything on the left bank of the Danube,–cities, fortresses, and lands, all with the view to their future annexation to Russia.

The territory ceded to Russia by the peace of Adrianople included the Caucasus,–a mountainous region inhabited by several independent races, among which were the Circassians, who acknowledged allegiance neither to Turkey nor Russia. Nicholas at first attempted to gain over the chieftains of these different nations or tribes by bribes, pensions, decorations, and military appointments. He finally was obliged to resort to arms, but without complete success.

Such, in brief, were the acquisitions of Russia during the reign of Nicholas down to the time of the Crimean war, which made him perhaps the most powerful sovereign in the world. As Czar of all the Russias there were no restraints on his will in his own dominions, and it was only as he was held in check by the different governments of Europe, jealous of his encroachments, that he was reminded that he was not omnipotent.

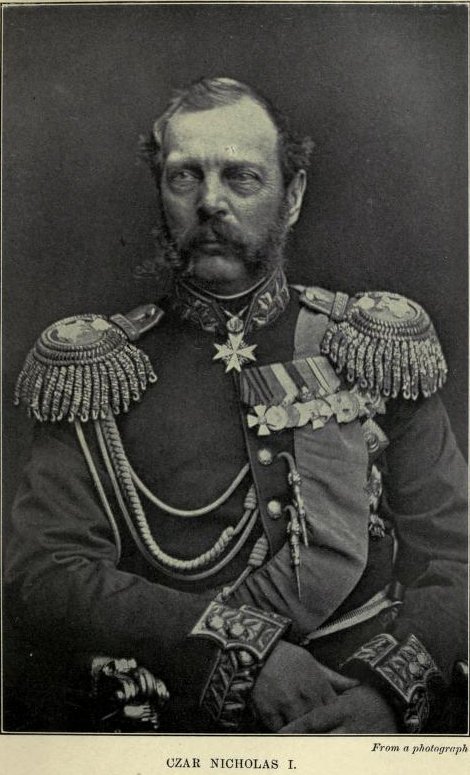

For fifteen years after his accession to the throne Nicholas had the respect of Europe. He was moral in his domestic relations, fond of his family, religious in his turn of mind, bordering on superstition, a zealot in his defence of the Greek Church, scrupulous in the performance of his duties, and a man of his word. The Duke of Wellington was his admiration,–a model for a sovereign to imitate. Nicholas was not so generous and impulsive as his brother Alexander, but more reliable. In his personal appearance he made a fine impression,–over six feet in height, with a frank and open countenance, but not expressive of intellectual acumen. His will, however, was inflexible, and his anger was terrible. His passionate temper, which gave way to bursts of wrath, was not improved by his experiences. As time advanced he withdrew more and more within himself, and grew fitful and jealous, disinclined to seek advice, and distrustful of his counsellors; and we can scarcely wonder at this result when we consider his absolute power and unfettered will.

Few have been the kings and emperors who resembled Marcus Aurelius, who was not only master of the world, but master of himself. Few indeed have been the despots who have refrained from acts of cruelty, or who have uniformly been governed by reason. Even in private life, very successful men have an imperious air, as if they were accustomed to submission and deference; but a monarch of Russia, how can he be otherwise than despotic and self-conscious? Everybody he sees, every influence to which he is subjected, tends to swell his egotism. What changes of character marked Saul, David, and Solomon! So of Nicholas, as of the ancient Caesars. With the advance of years and experience, his impatience grew under opposition and his rage under defeat. No man yet has lived, however favored, that could always have his way. He has to yield to circumstances,–not only to those great ones which he may own to have been determined by Divine Providence, but also to those unforeseen impediments which come from his humblest instruments. He cannot prevent deceit, hypocrisy, and treachery on the part of officials, any easier than one can keep servants from lying and cheating. Who is not in the power, more or less, of those who are compelled to serve; and when an absolute monarch discovers that he has been led into mistakes by treacherous or weak advisers, how natural that his temper should be spoiled!

Thus was Nicholas in the latter years of his reign. He was thwarted by foreign Powers, and deceived by his own instruments of despotic rule. He found himself only a man, and like other men. He became suspicious, bitter, and cruel. His pride was wounded by defeat and opposition from least expected quarters. He found his burdens intolerable to bear. His cares interfered with what were once his pleasures. The dreadful load of public affairs, which he could not shake off, weighed down his soul with anxiety and sorrow. He realized, more than most monarchs, the truth of one of Shakespeare’s incomparable utterances,–

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

The mistakes and disappointments of the Crimean war finally broke his heart; and he, armed with more power than any one man in the world, died with the consciousness of a great defeat.

It would be interesting to show how seldom the great rulers of this world have had an unchecked career to the close of their lives. Most of them have had to ruminate on unexpected falls,–like Napoleon, Louis Philippe, Metternich, Gladstone, Bismarck,–or on unattained objects of ambition, like the great statesmen who have aspired to be presidents of the United States. Nicholas thought that the capital of the “sick man” was, like ripe fruit, ready to fall into his hands. After one hundred years of war, Russia discovered that this prize was no nearer her grasp. Nicholas, at the head of a million of disciplined troops, was defeated; while his antagonist, the “sick man,” could scarcely muster a fifth part of the number, and yet survived to plague his thwarted will.

The obstacles to the conquest of Constantinople by Russia are, after all, very great. There are only three ways by which a Russian general can gain this coveted object of desire. The one which seems the easiest is to advance by sea from Sebastopol, through the Black Sea, to the Bosphorus, with a powerful fleet. But Turkey has or had a fleet of equal size, while her allies, England and France, can sweep with ease from the Black Sea any fleet which Russia can possibly collect.

The ordinary course of Russian troops has been to cross the Pruth, which separates Russia from Moldavia, and advance through the Danubian provinces to the Balkans, dividing Bulgaria from Turkey in Europe. Once the Russian armies succeeded, amid innumerable difficulties, in conquering all the fortresses in the way, like Silistria, Varna, and Shumla; in penetrating the mountain passes of the Balkans, and making their way to Adrianople. But they were so demoralized, or weakened and broken, by disasters and privations, that they could get no farther than Adrianople with safety, and their retreat was a necessity. And had the Balkan passes been properly defended, as they easily could have been, even a Napoleon could not have penetrated them with two hundred thousand men, or any army which the Russians could possibly have brought there.

The third way open to the Russians in their advance to Constantinople is to march the whole extent of the northern shores of the Black Sea, and then cross the Caucasian range to the south, and advance around through Turkey in Asia, its entire width from east to west, amidst a hostile and fanatical population ready to die for their faith and country,–a way so beset with difficulties and attended with such vast expense that success would be almost impossible, even with no other foes than Turks.

The Emperor Nicholas was by nature stern and unrelenting. He had been merciless in his treatment of the Poles. When he was friendly, his frankness had an irresistible charm. During his twenty-seven years on the throne he had both “reigned and governed.” However, he was military, without being warlike. With no talents for generalship, he bestowed almost incredible attention upon the discipline of his armies. He oppressively drilled his soldiers, without knowledge of tactics and still less of strategy. Half his time was spent in inspecting his armies. When, in 1828, he invaded Turkey, his organizations broke down under an extended line of operations. For a long time thereafter he suffered the Porte to live in repose, not being ready to destroy it, waiting for his opportunity.

When the Pasha of Egypt revolted from the Sultan, and his son Ibrahim seriously threatened the dismemberment of Turkey, England and France interfered in behalf of Turkey; and in 1840 a convention in London placed Turkey under the common safeguard of the five great Powers,–England, France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia,–instead of the protectorate exercised by Russia alone. After the fall of Hungary, a number of civil and military leaders took refuge in Turkey, and Russia and Austria demanded the expulsion of the refugees, which was peremptorily refused by the Sultan. In consequence, Russia suspended all diplomatic intercourse with Turkey, and sought a pretext for war. In 1844 the Czar visited England, doubtless with the purpose of winning over Lord Aberdeen, then foreign secretary, and the Duke of Wellington, on the ground that Turkey was in a state of hopeless decrepitude, and must ultimately fall into his hands. In this event he was willing that England, as a reward for her neutrality, should take possession of Egypt.

It is thus probable that the Emperor Nicholas, after the failure of his armies to reach Constantinople through the Danubian provinces and across the Balkans, meditated, after twenty years of rest and recuperation, the invasion of Constantinople by his fleet, which then controlled the Black Sea.

But he reckoned without his host. He was deceived by the pacific attitude of England, then ruled by the cabinet of Lord Aberdeen, who absolutely detested war. The premier was almost a fanatic in his peace principles, and was on the most friendly terms with Nicholas and his ministers. The Czar could not be made to believe that England, under the administration of Lord Aberdeen, would interfere with his favorite and deeply meditated schemes of conquest. He saw no obstacles except from the Turks themselves, timid and stricken with fears; so he strongly fortified Sebastopol and made it impregnable by the sea, and quietly gathered in its harbor an immense fleet, with which the Turkish armaments could not compare. The Turkish naval power had never recovered from the disaster which followed the battle of Navarino, when their fleet was annihilated. With a crippled naval power and decline in military strength, with defeated armies and an empty purse, it seemed to the Czar that Turkey was crushed in spirit and Constantinople defenceless; and that impression was strengthened by the representation of his ambassador at the Porte,–Prince Mentchikof, who almost openly insulted the Sultan by his arrogance, assumptions, and threats.

But a very remarkable man happened at that time to reside at Constantinople as the ambassador of England, one in whom the Turkish government had great confidence, and who exercised great influence over it. This man was Sir Stratford Canning (a cousin of the great Canning), who in 1852 was made viscount, with the title Lord Stratford de Redcliffe. He was one of the ablest diplomatists then living, or that England had ever produced, and all his sympathies were on the side of Turkey. Mentchikof was no match for the astute Englishman, who for some time controlled the Turkish government, and who baffled all the schemes of Nicholas.

England–much as she desired the peace of Europe, and much as Lord Aberdeen detested war–had no intention of allowing the “sick man” to fall into the hands of Russia, and through her ambassador at Constantinople gave encouragement to Turkey to resist the all-powerful Russia with the secret promise of English protection; and as Lord Stratford distrusted and disliked Russia, having since 1824 been personally engaged in Eastern diplomacy and familiar with Russian designs, he very zealously and with great ability fought the diplomatic battles of Turkey, and inspired the Porte with confidence in the event of war. It was by his dexterous negotiations that England was gradually drawn into a warlike attitude against Russia, in spite of the resolutions of the English premier to maintain peace at any cost.

In the meantime the English people, after their long peace of nearly forty years, were becoming restless in view of the encroachments of Russia, and were in favor of vigorous measures, even if they should lead to war. The generation had passed away that remembered Waterloo, so that public opinion was decidedly warlike, and goaded on the ministry to measures which materially conflicted with Lord Aberdeen’s peace principles. The idea of war with Russia became popular,–partly from jealousy of a warlike empire that aspired to the possession of Constantinople, and partly from the English love of war itself, with its excitements, after the dulness and inaction of a long period of peace and prosperity. In 1853 England found herself drifting into war, to the alarm and disgust of Aberdeen and Gladstone, to the joy of the people and the satisfaction of Palmerston and a majority of the cabinet.

The third party to this Crimean contest was France, then ruled by Louis Napoleon, who had lately become head of the State by a series of political usurpations and crimes that must ever be a stain on his fame. Yet he did not feel secure on his throne; the ancient nobles, the intellect of the country, and the parliamentary leaders were against him. They stood aloof from his government, regarding him as a traitor and a robber, who by cunning and slaughter had stolen the crown. He was supposed to be a man of inferior intellect, whose chief merit was the ability to conceal his thoughts and hold his tongue, and whose power rested on the army, the allegiance of which he had seduced by bribes and promises. Feeling the precariousness of his situation, and the instability of the people he had deceived with the usual Napoleonic lies, which he called “ideas,” he looked about for something to divert their minds,–some scheme by which he could gain éclat; and the difficulties between Russia and Turkey furnished him the occasion he desired. He determined to employ his army in aid of Turkey. It would be difficult to show what gain would result to France, for France did not want additional territory in the East. But a war would be popular, and Napoleon wanted popularity. Moreover, an alliance with England, offensive and defensive, to check Russian encroachments, would strengthen his own position, social as well as political. He needed friends. It was his aim to enter the family of European monarchs, to be on a good footing with them, to be one of them, as a legitimate sovereign. The English alliance might bring Victoria herself to Paris as his guest. The former prisoner of Ham, whom everybody laughed at as a visionary or despised as an adventurer, would, by an alliance with England, become the equal of Queen Victoria, and with infinitely greater power. She was a mere figure-head in her government, to act as her ministers directed; he, on the other hand, had France at his feet, and dictated to his ministers what they should do.

The parties, then, in the Crimean war were Russia, seeking to crush Turkey, with France and England coming to the rescue,–ostensibly to preserve the “balance of power” in Europe.

But before considering the war itself, we must glance at the preliminaries,–the movements which took place making war inevitable, and which furnished the pretext for disturbing the peace of Europe.

First must be mentioned the contest for the possession of the sacred shrines in the Holy Land. Pilgrimages to these shrines took place long before Palestine fell into the hands of the Mohammedans. It was one of the passions of the Middle Ages, and it was respected even by the Turks, who willingly entered into the feelings of the Christians coming to kneel at Jerusalem. Many sacred objects of reverence, if not idolatry, were guarded by Christian monks, who were permitted by the government to cherish them in their convents. But the Greek and the Latin convents, allowed at Jerusalem by the Turkish government, equally aspired to the guardianship of the Holy Sepulchre and other sacred shrines in Jerusalem. It rested with the Turkish government to determine which of the rival churches, Greek or Latin, should have the control of the shrines, and it was a subject of perpetual controversy,–Russia, of course, defending the claims of the Greek convents, who at this time had long been the appointed guardians, and France now taking up those of the Latin; although Russia was the more earnest in the matter, as holding a right already allowed.

The new President of the French republic, in 1851, on the lookout for subjects of controversy with Russia, had directed his ambassador at Constantinople to demand from the Porte some almost forgotten grants made to the Latin Church two or three hundred years before. This demand, which the Sultan dared not refuse, was followed by the Turks’ annulling certain privileges which had long been enjoyed by the Greek convents; and thus the ancient dispute was reopened. The Greek Church throughout Russia was driven almost to frenzy by this act of the Turkish government. The Czar Nicholas, himself a zealot in religion, was indignant and furious; but the situation gave him a pretext for insults and threats that would necessarily lead to war, which he desired as eagerly as Louis Napoleon. The Porte, embarrassed and wishing for peace, leaned for advice on the English ambassador, who, as has been said, promised the mediation of England.

Then followed a series of angry negotiations and pressure made by Russia and France alternately on the Sultan in reference to the guardianship of the shrines,–as to who should possess the key of the chief door of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem and of the church at Bethlehem, Greek or Latin monks.

As the pressure made by France was the most potent, the Czar in his rage ordered one of his corps d’armée to advance to the frontiers of the Danubian provinces, and another corps to hold itself in readiness,–altogether a force of one hundred and forty-four thousand men. The world saw two great nations quarrelling about a key to the door of a church in Palestine; statesmen saw, on the one hand, the haughty ambition of Nicholas seeking pretence for a war which might open to him the gates of Constantinople, and, on the other hand, the schemes of the French emperor–for the ten-year president elected in 1851 had in just one year got himself “elected” emperor–to disturb the peace of Europe, which might end in establishing more securely his own usurpation.

The warlike attitude of Russia in 1853 alarmed England, who was not prepared to go to war. As has been said, Mentchikof was no match in the arts of diplomacy for Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, and an angry and lively war of diplomatic notes passed between them. The Czar discovered that the English ambassador had more influence with the Porte than Mentchikof, and became intensely angry. Lord Stratford ferreted out the schemes of the Czar in regard to the Russian protectorate of the Greek Church, which was one of his most cherished plans, and bent every energy to defeat it. He did not care about the quarrels of the Greek and Latin monks for the guardianship of the sacred shrines; but he did object to the meditated protectorate of the Czar over the Greek subjects of Turkey, which, if successful, would endanger the independence of the Sultan, so necessary for the peace of Europe. All the despatches from. St. Petersburg breathed impatience and wrath, and Mentchikof found himself in great difficulties. The Russian ambassador even found means to have the advantage of a private audience with the Sultan, without the knowledge of the grand vizier; but the Sultan, though courteous, remained firm. This ended the mission of the Russian ambassador, foiled and baffled at every turn; while his imperial master, towering into passion, lost all the reputation he had gained during his reign for justice and moderation.

Within three days of the departure of Prince Mentchikof from Constantinople, England and France began to concert measures together for armed resistance to Russia, should war actually break out, which seemed inevitable, for the Czar was filled with rage; and this in spite of the fact that within two weeks the Sultan yielded the point as to the privileges of Greek subjects in his empire,–but beyond that he stood firm, and appealed to England and France.

The Czar now meditated the occupation of the Danubian principalities, in order to enable his armies to march to Constantinople. But Austria and Prussia would not consent to this, and the Czar found himself opposed virtually by all Europe. He still labored under the delusion that England would hold aloof, knowing the peace policy of the English government under the leadership of Lord Aberdeen. Under this delusion, and boiling over with anger, he suddenly, without taking counsel of his ministers or of any living soul, touched a bell in his palace. The officer in attendance received an order for the army to cross the Pruth. On the 2d of July, 1853, Russia invaded the principalities. On the following day a manifesto was read in her churches that the Czar made war on Turkey in defence of the Greek religion; and all the fanatical zeal of the Russians was at once excited to go where the Czar might send them in behalf of their faith. Nothing could be more popular than such a war.

But the hostile attitude taken by all Europe on the invasion of the principalities, and by Austria in particular, was too great an obstacle for even the Czar of all the Russias to disregard, especially when he learned that the fleets of France and England were ordered to the Dardanelles, and that his fleet would be pent up in an inland basin of the Black Sea. It became necessary for Russia to renew negotiations. At Vienna a note had been framed between four of the great Powers, by which it was clear that they would all unite in resisting the Czar, if he did not withdraw his armies from the principalities. The Porte promptly determined on war, supported by the advice of a great Council, attended by one hundred and seventy-two of the foremost men of the empire, and fifteen days were given to Russia to withdraw her troops from the principalities. At the expiration of that term, the troops not being withdrawn, on October 5 war was declared by Turkey.

The war on the part of Turkey was defensive, necessary, and popular. The religious sentiment of the whole nation was appealed to, and not in vain. It is difficult for any nation to carry on a great war unless it is supported by the people. In Turkey and throughout the scattered dominions of the Sultan, religion and patriotism and warlike ardor combined to make men arise by their own free-will, and endure fatigue, danger, hunger, and privation for their country and their faith. The public dangers were great; for Russia was at the height of her power and prestige, and the Czar was known to have a determined will, not to be bent by difficulties which were not insurmountable.

Meanwhile the preachers of the Orthodox Greek faith were not behind the Mohammedans in rousing the martial and religious spirit of nearly one hundred millions of the subjects of the Russian autocrat. In his proclamation the Czar urged inviolable guaranties in favor of the sacred rights of the Orthodox Church, and pretended (as is usual with all parties in going to war) that he was challenged to the fight, and that his cause was just. He then invoked the aid of Almighty Power. It was rather a queer thing for a warlike sovereign, entering upon an aggressive war to gratify ambition, to quote the words of David: “In thee, O Lord, have I trusted: let me not be confounded forever.”

Urged on and goaded by the French emperor, impatient of delay, and obtuse to all further negotiations for peace, which Lord Aberdeen still hoped to secure, the British government at last gave orders for its fleet to proceed to Constantinople. The Czar, so long the ally of England, was grieved and indignant at what appeared to him to be a breach of treaties and an affront to him personally, and determined on vengeance. He ordered his fleet at Sebastopol to attack a Turkish fleet anchored near Sinope, which was done Nov. 30, 1853. Except a single steamer, every one of the Turkish vessels was destroyed, and four thousand Turks were killed.

The anger of both the French and English people was now fairly roused by this disaster, and Lord Aberdeen found himself powerless to resist the public clamor for war. Lord Palmerston, the most popular and powerful minister that England had, resigned his seat in the cabinet, and openly sided with the favorite cause. Lord Aberdeen was compelled now to let matters take their course, and the English fleet was ordered to the Black Sea; but war was not yet declared by the Western Powers, since there still remained some hopes of a peaceful settlement.

Meanwhile Prussia and Austria united in a league, offensive and defensive, to expel the Russians from the Danubian provinces, which filled the mind of Nicholas with more grief than anger; for he had counted on the neutrality of Austria and Prussia, as he had on the neutrality of England. It was his misfortune to believe what he wished, rather than face facts.

On the 27th of March, 1854, however, after a winter of diplomacy and military threatenings and movements, which effected nothing like a settlement, France and England declared war against Russia; on the 11th of April the Czar issued his warlike manifesto, and Europe blazed with preparations for one of the most needless and wicked contests in modern times. All parties were to blame; but on Russia the greatest odium rests for disturbing the peace of Europe, although the Czar at the outset had no idea of fighting the Western Powers. In a technical point of view the blame of beginning the dispute which led to the Crimean war rests with France, for she opened and renewed the question of the guardianship of the sacred shrines, which had long been under the protection of the Greek Church; and it was the intrigues of Louis Napoleon which entangled England. The latter country was also to blame for her jealousy of Russian encroachments, fearing that they would gradually extend to English possessions in the East. Had Nicholas known the true state of English public opinion he might have refrained from actual hostilities; but he was misled by the fact that Lord Aberdeen had given assurances of a peace policy.

Although France and England entered upon the war only with the intention at first of protecting Turkey, and were mere allies for that purpose, yet these two Powers soon bore the brunt of the contest, which really became a strife between Russia on the one side and England and France on the other. Moreover, instead of merely defending Turkey against Russia, the allied Powers assumed the offensive, and thus took the responsibility for all the disastrous consequences of the war.

The command of the English army had been intrusted to Lord Raglan, once known as Lord Fitzroy Somerset, who lost an arm at the battle of Waterloo while on the staff of Wellington; a wise and experienced commander, but too old for such service as was now expected of him in an untried field of warfare. Besides, it was a long time since he had seen active service. When appointed to the command he was sixty-six years old. From 1827 to 1852 he was military secretary at the Horse Guards,–the English War Office,–where he was made master-general of the Ordnance, and soon after became a full general. He was taciturn but accessible, and had the power of attracting everybody to him; averse to all show and parade; with an uncommon power for writing both good English and French,–an accomplished man, from whom much was expected.

The command of the French forces was given to Marshal Saint-Arnaud, a bold, gay, reckless, enterprising man, who had distinguished himself in Algeria as much for his indifference to human life as for his administrative talents,–ruthless, but not bloodthirsty. He was only colonel when Fleury, the arch-conspirator and friend of Louis Napoleon, was sent to Algeria to find some officer of ability who could be bribed to join in the meditated coup d’état. Saint-Arnaud listened to his proposals, and was promised the post of minister of war, which would place the army under his control, for all commanders would receive orders from him. He was brought to Paris and made minister of war, with a view to the great plot of the 2d of December, and later was created a Marshal of France. His poor health (the result of his excesses) made him unfit to be intrusted with the forces for the invasion of the Crimea; but his military reputation was better than his moral, and in spite of his unfitness the emperor–desirous still further to reward his partisan services–put him in command of the French Crimean forces.

The first military operations took place on the Danube. The Russians then occupied the Danubian principalities, and had undertaken the siege of Silistria, which was gallantly defended by the Turks, before the allied French and English armies could advance to its relief; but it was not till the middle of May that the allied armies were in full force, and took up their position at Varna.

Nicholas was now obliged to yield. He could not afford to go to war with Prussia, Austria, France, England, and Turkey together. It had become impossible for him to invade European Turkey by the accustomed route. So, under pressure of their assembling forces, he withdrew his troops from the Danubian provinces, which removed all cause of hostilities from Prussia and Austria. These two great Powers now left France and England to support all the burdens of the war. If Prussia and Austria had not withdrawn from the alliance, the Crimean war would not have taken place, for Russia would have made peace with Turkey. It was on the 2d of August, 1854, that the Russians recrossed the Pruth, and the Austrians took possession of the principalities.

England might now have withdrawn from the contest but for her alliance with France,–an entangling alliance, indeed; but Lord Palmerston, seeing that war was inevitable, withdrew his resignation, and the British cabinet became a unit, supported by the nation. Lord Aberdeen still continued to be premier; but Palmerston was now the leading spirit, and all eyes turned to him. The English people, who had forgotten what war was, upheld the government, and indeed goaded it on to war. The one man who did not drift was the secretary for foreign affairs, Lord Palmerston, who went steadily ahead, and gained his object,–a check upon Russia’s power in the East.

This statesman was a man of great abilities, with a strong desire for power under the guise of levity and good-nature. He was far-reaching, bold, and of concentrated energy; but his real character was not fully comprehended until the Crimean war, although he was conspicuous in politics for forty years. His frank utterances, his off-hand manner, his ready banter, and his joyous eyes captivated everybody, and veiled his stern purposes. He was distrusted at St. Petersburg because of his alliance with Louis Napoleon, his hatred of the Bourbons, and his masking the warlike tendency of the government which he was soon to lead, for Lord Aberdeen was not the man to conduct a war with Russia.

At this point, as stated above, the war might have terminated, for the Russians had abandoned the principalities; but at home the English had been roused by Louis Napoleon’s friends and by the course of events to a fighting temper, and the French emperor’s interests would not let him withdraw; while in the field neither the Turkish nor French nor English troops were to be contented with less than the invasion of the Russian territories. Turkey was now in no danger of invasion by the Russians, for they had been recalled from the principalities, and the fleets of England and France controlled the Black Sea. From defensive measures they turned to offensive.

The months of July and August were calamitous to the allied armies at Varna; not from battles, but from pestilence, which was fearful. On the 26th of August it was determined to re-embark the decimated troops, sail for the Crimea, and land at some place near Sebastopol. The capture of this fortress was now the objective point of the war. On the 13th of September the fleets anchored in Eupatoria Bay, on the west coast of the Crimean peninsula, and the disembarkation of the troops took place without hindrance from the Russians, who had taken up a strong position on the banks of the Alma, which was apparently impregnable. There the Russians, on their own soil and in their intrenched camp, wisely awaited the advance of their foes on the way to Sebastopol, the splendid seaport, fortress, and arsenal at the extreme southwestern point of the Crimea.

There were now upon the coasts of the Crimea some thirty-seven thousand French and Turks with sixty-eight pieces of artillery (all under the orders of Marshal Saint-Arnaud), and some twenty-seven thousand English with sixty guns,–altogether about sixty-four thousand men and one hundred and twenty-eight guns. It was intended that the fleets should follow the march of the armies, in order to furnish the necessary supplies. The march was perilous, without a base of supplies on the coast itself, and without a definite knowledge of the number or resources of the enemy. It required a high order of military genius to surmount the difficulties and keep up the spirits of the troops. The French advanced in a line on the coast nearest the sea; the English took up their line of march towards the south, on the left, farther in the interior. The French were protected by the fleets on the one hand and by the English on the other. The English therefore were exposed to the greater danger, having their entire left flank open to the enemy’s fire. The ground over which the Western armies marched was an undulating steppe. They marched in closely massed columns, and they marched in weariness and silence, for they had not recovered from the fatal pestilence at Varna. The men were weak, and suffered greatly from thirst. At length they came to the Alma River, where the Russians were intrenched on the left bank. The allies were of course compelled to cross the river under the fire of the enemies’ batteries, and then attack their fortified positions, and drive the Russians from their post.

All this was done successfully. The battle of the Alma was gained by the invaders, but only with great losses. Prince Mentchikof, who commanded the Russians, beheld with astonishment the defeat of the troops he had posted in positions believed to be secure from capture by assault. The genius of Lord Raglan, of Saint-Arnaud, of General Bosquet, of Sir Colin Campbell, of Canrobert, of Sir de Lacy Evans, of Sir George Brown, had carried the day. Both sides fought with equal bravery, but science was on the side of the allies. In the battle, Sir Colin Campbell greatly distinguished himself leading a Highland brigade; also General Codrington, who stormed the great redoubt, which was supposed to be impregnable. This probably decided the battle, the details of which it is not my object to present. Its great peculiarity was that the Russians fought in solid column, and the allies in extended lines.

After the day was won, Lord Raglan pressed Saint-Arnaud to the pursuit of the enemy; but the French general was weakened by illness, and his energies failed. Had Lord Raglan’s counsels been followed, the future disasters of the allied armies might have been averted. The battle was fought on the 20th of September; but the allied armies halted on the Alma until the 23d, instead of pushing on directly to Sebastopol, twenty-five miles to the south. This long halt was owing to Saint-Arnaud, who felt it was necessary to embark the wounded on the ships before encountering new dangers. This refusal of the French commander to advance directly to the attack of the forts on the north of Sebastopol was unfortunate, for there would have been but slight resistance, the main body of the Russians having withdrawn to the south of the city. All this necessitated a flank movement of the allies, which was long and tedious, eastward, across the north side of Sebastopol to the south of it, where the Russians were intrenched. They crossed the Belbec (a small river) without serious obstruction, and arrived in sight of Sebastopol, which they were not to enter that autumn as they had confidently expected. The Russian to whom the stubborn defence of Sebastopol was indebted more than to any other man,–Lieut.-Colonel Todleben,–had thoroughly and rapidly fortified the city on the north after the battle of the Alma.

It was the opinion of Todleben himself, afterward expressed,–which was that of Lord Raglan, and also of Sir Edmund Lyons, commanding the fleet,–that the Star Fort which defended Sebastopol on the north, however strong, was indefensible before the forces that the allies could have brought to bear against it. Had the Star Fort been taken, the whole harbor of Sebastopol would have been open to the fire of the allies, and the city–needed for refuge as well as for glory–would have fallen into their hands.

The condition of the allied armies was now critical, since they had no accurate knowledge of the country over which they were to march on the east of Sebastopol, nor of the strength of the enemy, who controlled the sea-shore. On the morning of the 25th of September the flank march began, through tangled forests, by the aid of the compass. It was a laborious task for the troops, especially since they had not regained their health from the ravages of the cholera in Bulgaria. Two days’ march, however, brought the English army to the little port of Balaklava, on the south of Sebastopol, where the land and sea forces met.

Soon after the allied armies had arrived at Balaklava, Saint-Arnaud was obliged by his fatal illness to yield up his command to Marshal Canrobert, and a few days later he died,–an unprincipled, but a brave and able man.

The Russian forces meanwhile, after the battle of the Alma, had retreated to Sebastopol in order to defend the city, which the allies were preparing to attack. Prince Mentchikof then resolved upon a bold measure for the defence of the city, and this was to sink his ships at the mouth of the harbor, by which he prevented the English and French fleets from entering it, and gained an additional force of eighteen thousand seamen to his army. Loath was the Russian admiral to make this sacrifice, and he expostulated with the general-in-chief, but was obliged to obey. This sinking of their fleet by the Russians reminds one of the conflagration of Moscow,–both desperate and sacrificial acts.

The French and English forces were now on the south side of Sebastopol, in communication with their fleet at Balaklava, and were flushed with victory, while the forces opposed to them were probably inferior in number. Why did not the allies at once begin the assault of the city? It was thought to be prudent to wait for the arrival of their siege guns. While these heavy guns were being brought from the ships, Todleben–the ablest engineer then living–was strengthening the defences on the south side. Every day’s delay added to the difficulties of attack. Three weeks of precious time were thus lost, and when on the 17th of October the allies began the bombardment of Sebastopol, which was to precede the attack, their artillery was overpowered by that of the defenders. The fleets in vain thundered against the solid sea-front of the fortress. After a terrible bombardment of eight days the defences of the city were unbroken.

Mentchikof, meanwhile, had received large reinforcements, and prepared to attack the allies from the east. His point of attack was Balaklava, the defence of which had been intrusted to Sir Colin Campbell. The battle was undecisive, but made memorable by the sacrifice of the “Light Brigade,”–about six hundred cavalry troops under the command of the Earl of Cardigan. This arose from a misunderstanding on the part of the Earl of Lucan, commander of the cavalry division, of an order from Lord Raglan to attack the enemy. Lord Cardigan was then directed by Lucan to rescue certain guns which the enemy had captured. He obeyed, in the face of batteries in front and on both flanks. The slaughter was terrible,–in fact, the brigade was nearly annihilated. The news of this disaster made a deep impression on the English nation, and caused grave apprehensions as to the capacity of the cavalry commanders, neither of whom had seen much military service, although both were over fifty years of age and men of ability and bravery. The “Heavy Brigade” of cavalry, commanded by General Scarlett, who also was more than fifty years old and had never seen service in the field, almost redeemed the error by which that commanded by Lord Cardigan was so nearly destroyed. With six hundred men he charged up a long slope, and plunged fearlessly into a body of three thousand Russian cavalry, separated it into segments, disorganized it, and drove it back,–one of the most brilliant cavalry operations in modern times.

The battle of Balaklava, on the 25th of October, was followed, November 5, by the battle of Inkerman, when the English were unexpectedly assaulted, under cover of a deep mist, by an overwhelming body of Russians. The Britons bravely stood their ground against the massive columns which Mentchikof had sent to crush them, and repelled the enemy with immense slaughter; but this battle made the capture of Sebastopol, as planned by the allies, impossible. The forces of the Russians were double in number to those of the allies, and held possession of a fortress against which a tremendous cannonade had been in vain. The prompt sagacity and tremendous energy of Todleben repaired every breach as fast as it was made; and by his concentration of great numbers of laborers at the needed points, huge earthworks arose like magic before the astonished allies. They made no headway; their efforts were in vain; the enterprise had failed. It became necessary to evacuate the Crimea, or undertake a slow winter siege in the presence of superior forces, amid difficulties which had not been anticipated, and for which no adequate provision had been made.

The allies chose the latter alternative; and then began a series of calamities and sufferings unparalleled in the history of war since the retreat of Napoleon from Moscow. First came a terrible storm on the 14th of November, which swept away the tents of the soldiers encamped on a plateau near Balaklava, and destroyed twenty-one vessels bringing ammunition and stores to the hungry and discouraged army. There was a want of everything to meet the hardships of a winter campaign on the stormy shores of the Black Sea,–suitable clothing, fuel, provisions, medicines, and camp equipage. It never occurred to the minds of those who ordered and directed this disastrous expedition that Sebastopol would make so stubborn a defence; but the whole force of the Russian empire which could be spared was put forth by the Emperor Nicholas, thus rendering necessary continual reinforcements from France and England to meet armies superior in numbers, and to supply the losses occasioned by disease and hardship greater than those on the battlefield. The horrors of that dreadful winter on the Crimean peninsula, which stared in the face not only the French and English armies but also the Russians themselves, a thousand miles from their homes, have never been fully told. They form one of the most sickening chapters in the annals of war.

Not the least of the misfortunes which the allies suffered was the loss of the causeway, or main road, from Balaklava to the high grounds where they were encamped. It had been taken by the Russians three weeks before, and never regained. The only communication from the camp to Balaklava, from which the stores and ammunition had to be brought, was a hillside track, soon rendered almost impassable by the rains. The wagons could not be dragged through the mud, which reached to their axles, and the supplies had to be carried on the backs of mules and horses, of which there was an insufficient number. Even the horses rapidly perished from fatigue and hunger.

Thus were the French and English troops pent up on a bleak promontory, sick and disheartened, with uncooked provisions, in the middle of winter. Of course they melted away even in the hospitals to which they were sent on the Levant. In those hospitals there was a terrible mortality. At Scutari alone nine thousand perished before the end of February, 1855.

The reports of these disasters, so unexpected and humiliating, soon reached England through the war correspondents and private letters, and produced great exasperation. The Press was unsparing in its denunciations of the generals, and of the ministry itself, in not providing against the contingencies of the war, which had pent up two large armies on a narrow peninsula, from which retreat was almost impossible in view of the superior forces of the enemy and the dreadful state of the roads. The armies of the allies had nothing to do but fight the elements of Nature, endure their unparalleled hardships the best way they could, and patiently await results.

The troops of both the allied nations fought bravely and behaved gallantly; but they fought against Nature, against disease, against forces vastly superior to themselves in number. One is reminded, in reading the history of the Crimean war, of the ancient crusaders rather than of modern armies with their vast scientific machinery, so numerous were the mistakes, and so unexpected were the difficulties of the attacking armies. One is amazed that such powerful and enlightened nations as the English and French could have made so many blunders. The warning voices of Aberdeen, of Gladstone, of Cobden, of Bright, against the war had been in vain amid the tumult of military preparations; but it was seen at last that they had been thy true prophets of their day.

Nothing excited more commiseration than the dreadful state of the hospitals in the Levant, to which the sick and wounded were sent; and this terrible exigency brought women to the rescue. Their volunteered services were accepted by Mr. Sidney Herbert, the secretary-at-war, and through him by the State. On the 4th of November Florence Nightingale, called the “Lady-in-Chief,” disembarked at Scutari and began her useful and benevolent mission,–organizing the nurses, and doing work for which men were incapable,–in those hospitals infected with deadly poisons.

The calamities of a questionable war, made known by the Press, at last roused public indignation, and so great was the popular clamor that Lord Aberdeen was compelled to resign a post for which he was plainly incapable,–at least in war times. He was succeeded by Lord Palmerston,–the only man who had the confidence of the nation. In the new ministry Lord Panmure (Fox Maule) succeeded the Duke of Newcastle as minister of war.

After midwinter the allied armies began to recover their health and strength, through careful nursing, better sanitary measures, and constant reinforcements, especially from France. At last a railway was made between Balaklava and the camps, and a land-transport corps was organized. By March, 1855, cattle in large quantities were brought from Spain on the west and Armenia on the east, from Wallachia on the north and the Persian Gulf on the south. Seventeen thousand men now provided the allied armies with provisions and other supplies, with the aid of thirty thousand beasts of burden.

It was then that Sardinia joined the Western Alliance with fifteen thousand men,–an act of supreme wisdom on the part of Cavour, since it secured the friendship of France in his scheme for the unity of Italy. A new plan of operations was now adopted by the allies, which was for the French to attack Sebastopol at the Malakoff, protecting the city on the east, while the English concentrated their efforts on the Redan, another salient point of the fortifications. In the meantime Canrobert was succeeded in the command of the French army by Pélissier,–a resolute soldier who did not owe his promotion to complicity in the coup d’état.

On the 18th of June a general assault was made by the combined armies–now largely reinforced–on the Redan and the Malakoff, but they were driven back by the Russians with great loss; and three months more were added to the siege. Fatigue, anxiety, and chagrin now carried off Lord Raglan, who died on the 28th of June, leaving the command to General Simpson. By incessant labors the lines of the besiegers were gradually brought nearer the Russian fortifications. On the 16th of August the French and Sardinians gained a decisive victory over the Russians, which prevented Sebastopol from receiving further assistance from without. On September 9 the French succeeded in storming the Malakoff, which remained in their hands, although the English were unsuccessful in their attack upon the Redan. On the fall of the Malakoff the Russian commander blew up his magazines, while the French and English demolished the great docks of solid masonry, the forts, and defences of the place. Thus Sebastopol, after a siege of three hundred and fifty days, became the prize of the invaders, at a loss, on their part, of a hundred thousand men, and a still greater loss on the part of the defenders, since provisions, stores, and guns had to be transported at immense expense from the interior of Russia. In Russia there was no free Press to tell the people of the fearful sacrifices to which they had been doomed; but the Czar knew the greatness of his losses, both in men and military stores; and these calamities broke his heart, for he died before the fall of the fortress which he had resolved to defend with all the forces of his empire. Probably three hundred thousand Russians had perished in the conflict, and the resources of Russia were exhausted.

France had now become weary of a war which brought so little glory and entailed such vast expense. England, however, would have continued the war at any expense and sacrifice if Louis Napoleon had not secretly negotiated with the new Czar, Alexander II.; for England was bent on such a crippling of Russia as would henceforth prevent that colossal power from interfering with the English possessions in the East, which the fall of Kars seemed to threaten. The Czar, too, would have held out longer but for the expostulation of Austria and the advice of his ministers, who pointed out his inability to continue the contest with the hostility of all Europe.

On the 25th of February, 1856, the plenipotentiaries of the great Powers assembled in Paris, and on the 30th of March the Treaty of Paris was signed, by which the Black Sea was thrown open to the mercantile marine of all nations, but interdicted to ships of war. Russia ceded a portion of Bessarabia, which excluded her from the Danube; and all the Powers guaranteed the independence of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of fourteen years, the downfall of Louis Napoleon enabled Russia to declare that it would no longer recognize the provisions of a treaty which excluded its war-ships from the Black Sea. England alone was not able to resist the demands of Russia, and in consequence Sebastopol arose from its ruins as powerful as ever.

The object, therefore, for which England and France went to war–the destruction of Russian power on the Black Sea–was only temporarily gained. From three to four hundred thousand men had been sacrificed among the different combatants, and probably not less than a thousand million dollars in treasure had been wasted,–perhaps double that sum. France gained nothing of value, while England lost military prestige. Russia undoubtedly was weakened, and her encroachments toward the East were delayed; but to-day that warlike empire is in the same relative position that it was when the Czar sent forth his mandate for the invasion of the Danubian principalities. In fact, all parties were the losers, and none were the gainers, by this needless and wicked war,–except perhaps the wily Napoleon III., who was now firmly seated on his throne.

The Eastern question still remains unsettled, and will remain unsettled until new complications, which no genius can predict, shall re-enkindle the martial passions of Europe. These are not and never will be extinguished until Christian civilization shall beat swords into ploughshares. When shall be this consummation of the victories of peace?

Authorities.

A. W. Kinglake’s Invasion of the Crimea; C. de Bazancourt’s Crimean Expedition; G. B. McClellan’s Reports on the Art of War in Europe in 1855-1856; R. C. McCormick’s Visit to the Camp before Sebastopol; J. D. Morell’s Neighbors of Russia, and History of the War to the Siege of Sebastopol; Pictorial History of the Russian War; Russell’s British Expedition to the Crimea; General Todleben’s History of the Defence of Sebastopol; H. Tyrrell’s History of the War with Russia; Fyffe’s History of Modern Europe; Life of Lord Palmerston; Life of Louis Napoleon.