Frederic the Great : The Prussian Power – Beacon Lights of History, Volume VIII : Great Rulers

Beacon Lights of History, Volume VIII : Great Rulers

Alfred the Great : The Saxons in England

Queen Elizabeth : Woman as a Sovereign

Henry of Navarre : The Huguenots

Gustavus Adolphus : Thirty Years’ War

Cardinal Richelieu : Absolutism

Oliver Cromwell : English Revolution

Louis XIV : The French Monarchy

Louis XV : Remote Causes of Revolution

Peter the Great : His Services to Russia

Frederic the Great : The Prussian Power

Beacon Lights of History, Volume VIII : Great Rulers

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Characteristics of the man

Education of Frederic II.

His character

Becomes King

Seizure of a part of Liège

Seizure of Silesia

Maria Theresa

Visit of Voltaire

Friendship between Voltaire and Frederic

Coalition against Frederic

Seven Years’ War

Carlyle’s History of Frederic

Empress Elizabeth of Russia

Decisive battles of Rossbach, Luthen, and Zorndorf

Heroism and fortitude of Frederic

Results of the Seven Years’ War

Partition of Poland

Development of the resources of Prussia

Public improvements

General services of Frederic to his country

His character

His ultimate influence

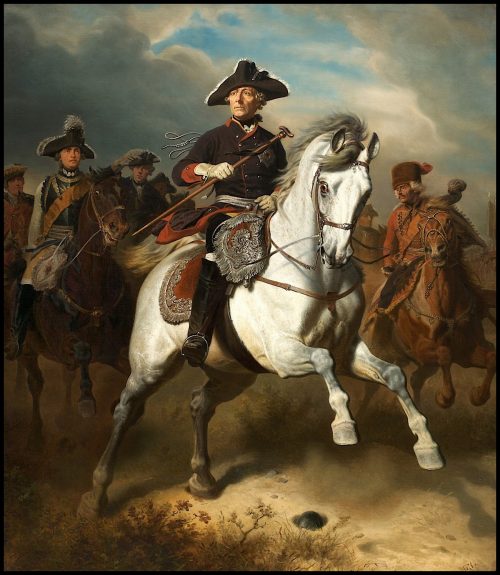

Frederic the Great : The Prussian Power

A.D. 1712-1786.

The history of Frederic the Great is simply that of a man who committed an outrageous crime, the consequences of which pursued him in the maledictions and hostilities of Europe, and who fought bravely and heroically to rescue himself and country from the ruin which impended over him as a consequence of this crime. His heroism, his fertility of resources, his unflagging energy, and his amazing genius in overcoming difficulties won for him the admiration of that class who idolize strength and success; so that he stands out in history as a struggling gladiator who baffled all his foes,–not a dying gladiator on the arena of a pagan amphitheatre, but more like a Judas Maccabaeus, when hunted by the Syrian hosts, rising victorious, and laying the foundation of a powerful monarchy; indeed, his fame spread, irrespective of his cause and character, from one end of Christendom to the other,–not such a fame as endeared Gustavus Adolphus to the heart of nations for heroic efforts to save the Protestant religion,–but such a fame as the successful generals of ancient Rome won by adding territories to a warlike State, regardless of all the principles of right and wrong. Such a career is suggestive of grand moral lessons; and it is to teach these lessons that I describe a character for whom I confess I feel but little sympathy, yet whom I am compelled to respect for his heroic qualities and great abilities.

Frederic of Prussia was born in 1712, and had an unhappy childhood and youth from the caprices of a royal but disagreeable father, best known for his tall regiment of guards; a severe, austere, prejudiced, formal, narrow, and hypochondriacal old Pharisee, whose sole redeeming excellence was an avowed belief in God Almighty and in the orthodox doctrines of the Protestant Church.

In 1740, this rigid, exacting, unsympathetic king died; and his son Frederic, who had been subjected to the severest discipline, restraints, annoyances, and humiliations, ascended the throne, and became the third King of Prussia, at the age of twenty-eight. His kingdom was a small one, being then about one quarter of its present size.

And here we pause for a moment to give a glance at the age in which he lived,–an age of great reactions, when the stirring themes and issues of the seventeenth century were substituted for mockeries, levities, and infidelities; when no fierce protests were made except those of Voltaire against the Jesuits; when an abandoned woman ruled France, as the mistress of an enervated monarch; when Spain and Italy were sunk in lethargic forgetfulness, Austria was priest-ridden, and England was governed by a ring of selfish lauded proprietors; when there was no marked enterprise but the slave-trade; when no department of literature or science was adorned by original genius; and when England had no broader statesman than Walpole, no abler churchman than Warburton, no greater poet than Pope. There was a general indifference to lofty speculation. A materialistic philosophy was in fashion,–not openly atheistic, but arrogant and pretentious, whose only power was in sarcasm and mockery, like the satires of Lucian, extinguishing faith, godless and yet boastful,–an Epicureanism such as Socrates attacked and Paul rebuked. It found its greatest exponent in Voltaire, the oracle and idol of intellectual Europe. In short, it was an age when general cynicism and reckless abandonment to pleasure marked the upper-classes; an age which produced Chesterfield, as godless a man as Voltaire himself.

In this period of religious infidelity, moral torpor, fashionable mediocrity, unthinking pleasure-seeking, and royal orgies; when the people were spurned, insuited and burdened,–Frederic ascends an absolute throne. He is a young and fashionable philosopher. He professes to believe in nothing that ages of inquiry and study are supposed to have settled; he even ridicules the religious principles of his father. He ardently adopts everything which claims to be a novelty, but is not learned enough to know that what he supposes to be new has been exploded over and over again. He is liberal and tolerant, but does not see the logical sequence of the very opinions he indorses. He is also what is called an accomplished man, since he can play on an instrument, and amuse a dinner-party by jokes and stories. He builds a magnificent theatre, and collects statues, pictures, snuff-boxes, and old china. He welcomes to his court, not stern thinkers, but sneering and amusing philosophers. He employs in his service both Catholics and Protestants alike, since he holds in contempt the religion of both. He is free from animosities and friendships, and neither punishes those who are his enemies nor rewards those who are his friends. He apes reform, but shackles the press; he appoints able men in his service, but only those who will be his unscrupulous tools. He has a fine physique, and therefore is unceasingly active. He flies from one part of his kingdom to another, not to examine morals or education or the state of the people, but to inspect fortresses and to collect camps.

To such a man the development of the resources of his kingdom, the reform of abuses, and educational projects are of secondary importance; he gives his primary attention to raising and equipping armies, having in view the extension of his kingdom by aggressive and unjustifiable wars. He cares little for domestic joys or the society of women, and is incapable of sincere friendship. He has no true admiration for intellectual excellence, although he patronizes literary lions. He is incapable of any sacrifice except for his troops, who worship him, since their interests are identical with his own. In the camp or in the field he spends his time, amusing himself occasionally with the society of philosophers as cynical as himself. He has dreams and visions of military glory, which to him is the highest and greatest on this earth, Charles XII. being his model of a hero.

With such views he enters upon a memorable career. His first important public act as king is the seizure of part of the territory of the Bishop of Liege, which he claims as belonging to Prussia. The old bishop is indignant and amazed, but is obliged to submit to a robbery which disgusts Christendom, but is not of sufficient consequence to set it in a blaze.

The next thing he does, of historical importance, is to seize Silesia, a province which belongs to Austria, and contains about twenty thousand square miles,–a fertile and beautiful province, nearly as large as his own kingdom; it is the highest table-land of Germany, girt around with mountains, hard to attack and easy to defend. So rapid and secret are his movements, that this unsuspecting and undefended country is overrun by his veteran soldiers as easily as Louis XIV. overran Flanders and Holland, and with no better excuse than the French king had. This outrage was an open insult to Europe, as well as a great wrong to Maria Theresa,–supposed by him to be a feeble woman who could not resent the injury. But in this woman he found the great enemy of his life,–a lioness deprived of her whelps, whose wailing was so piteous and so savage that she aroused Europe from lethargy, and made coalitions which shook it to its centre. At first she simply rallied her own troops, and fought single-handed to recover her lost and most valued province. But Frederic, with marvellous celerity and ability, got possession of the Silesian fortresses; the bloody battle of Mollwitz (1741) secured his prey, and he returned in triumph to his capital, to abide the issue of events.

It is not easy to determine whether this atrocious crime, which astonished Europe, was the result of his early passion for military glory, or the inauguration of a policy of aggression and aggrandizement. But it was the signal of an explosion of European politics which ended in one of the most bloody wars of modern times. “It was,” says Carlyle, “the little stone broken loose from the mountain, hitting others, big and little, which again hit others with their leaping and rolling, till the whole mountain-side was in motion under law of gravity.”

Maria Theresa appeals to her Hungarian nobles, with her infant in her arms, at a diet of the nation, and sends her envoys to every friendly court. She offers her unscrupulous enemy the Duchy of Limberg and two hundred thousand pounds to relinquish his grasp on Silesia. It is like the offer of Darius to Alexander, and is spurned by the Prussian robber. It is not Limberg he wants, nor money, but Silesia, which he resolves to keep because he wants it, and at any hazard, even were he to jeopardize his own hereditary dominions. The peace of Breslau gives him a temporary leisure, and he takes the waters of Aachen, and discusses philosophy. He is uneasy, but jubilant, for he has nearly doubled the territory and population of Prussia. His subjects proclaim him a hero, with immense paeans. Doubtless, too, he now desires peace,–just as Louis XIV. did after he had conquered Holland, and as Napoleon did when he had seated his brothers on the old thrones of Europe.

But there can be no lasting peace after such outrageous wickedness. The angered kings and princes of Europe are to become the instruments of eternal justice. They listen to the eloquent cries of the Austrian Empress, and prepare for war, to punish the audacious robber who disturbs the peace of the world and insults all other nationalities. But they are not yet ready for effective war; the storm does not at once break out.

The Austrians however will not wait, and the second Silesian war ensues, in which Saxony joins Austria. Again is Frederic successful, over the combined forces of these two powers, and he retains his stolen province. He is now regarded as a world-hero, for he has fought bravely against vastly superior forces, and is received in Berlin with unbounded enthusiasm. He renews his studies in philosophy, courts literary celebrities, reorganizes his army, and collects forces for a renewed encounter, which he foresees.

He has ten years of repose and preparation, during which he is lauded and nattered, yet retaining simplicity of habits, sleeping but five hours a day, finding time for state dinners, flute-playing, and operas, of all which he is fond; for he was doubtless a man of culture, social, well read if not profound, witty, inquiring, and without any striking defects save tyranny, ambition, parsimony, dissimulation, and lying.

It was during those ten years of rest and military preparation that Voltaire made his memorable visit–his third and last–to Potsdam and Berlin, thirty-two months of alternate triumph and humiliation. No literary man ever had so successful and brilliant a career as this fortunate and lauded Frenchman,–the oracle of all salons, the arbiter of literary fashions, a dictator in the realm of letters, with amazing fecundity of genius directed into all fields of labor; poet, historian, dramatist, and philosopher; writing books enough to load a cart, and all of them admired and extolled, all of them scattered over Europe, read by all nations; a marvellous worker, of unbounded wit and unexampled popularity, whose greatest literary merit was in the transcendent excellence of his style, for which chiefly he is immortal; a great artist, rather than an original and profound genius whose ideas form the basis of civilizations. The King of Prussia formed an ardent friendship for this king of letters, based on admiration rather than respect; invited him to his court, extolled and honored him, and lavished on him all that he could bestow, outside of political distinction. But no worldly friendship could stand such a test as both were subjected to, since they at last comprehended each other’s character and designs. Voltaire perceived the tyranny, the ambition, the heartlessness, the egotism, and the exactions of his royal patron, and despised him while he flattered him; and Frederic on his part saw the hollowness, the meanness, the suspicion, the irritability, the pride, the insincerity, the tricks, the ingratitude, the baseness, the lies of his distinguished guest,–and their friendship ended in utter vanity. What friendship can last without mutual respect? The friendship of Frederic and Voltaire was hopelessly broken, in spite of the remembrance of mutual admiration and happy hours. It was patched up and mended like a broken vase, but it could not be restored. How sad, how mournful, how humiliating is a broken friendship or an alienated love! It is the falling away of the foundations of the soul, the disappearance forever of what is most to be prized on earth,–its celestial certitudes. A beloved friend may die, but we are consoled in view of the fact that the friendship may be continued in heaven: the friend is not lost to us. But when a friendship or a love is broken, there is no continuance of it through eternity. It is the gloomiest thing to think of in this whole world.

But Frederic was too busy and pre-occupied a man to mourn long for a departed joy. He was absorbed in preparations for war. The sword of Damocles was suspended over his head, and he knew it better than any other man in Europe; he knew it from his spies and emissaries. Though he had enjoyed ten years’ peace, he knew that peace was only a truce; that the nations were arming in behalf of the injured empress; that so great a crime as the seizure of Silesia must be visited with a penalty; that there was no escape for him except in a tremendous life-and-death struggle, which was to be the trial of his life; that defeat was more than probable, since the forces in preparation against him were overwhelming. The curses of the civilized world still pursued him, and in his retreat at Sans-Souci he had no rest; and hence he became irritable and suspicious. The clouds of the political atmosphere were filled with thunderbolts, ready to fall upon him and crush him at any moment; indeed, nothing could arrest the long-gathering storm.

It broke out with unprecedented fury in the spring of 1756. Austria, Russia, Sweden, Saxony, and France were combined to ruin him,–the most powerful coalition of the European powers seen since the Thirty Years’ War. His only ally was England,–an ally not so much to succor him as to humble France, and hence her aid was timid and incompetent.

Thus began the famous Seven Years’ War, during which France lost her colonial possessions, and was signally humiliated at home,–a war which developed the genius of the elder Pitt, and placed England in the proud position of mistress of the ocean; a war marked by the largest array of forces which Europe had seen since the times of Charles V., in which six hundred thousand men were marshalled under different leaders and nations, to crush a man who had insulted Europe and defied the law of nations and the laws of God. The coalition represented one hundred millions of people with inexhaustible resources.

Now, it was the memorable resistance of Frederic II. to this vast array of forces, and his successful retention of the province he had seized, which gave him his chief claim as a hero; and it was his patience, his fortitude, his energy, his fertility of resources, and the enthusiasm with which he inspired his troops even after the most discouraging and demoralizing defeats, that won for him that universal admiration as a man which he lived to secure in spite of all his defects and crimes. We admire the resources and dexterity of an outlawed bandit, but we should remember he is a bandit still; and we confound all the laws which hold society together, when we cover up the iniquity of a great crime by the successes which have apparently baffled justice. Frederic II., by stealing Silesia, and thus provoking a great war of untold and indescribable miseries, is entitled to anything but admiration, whatever may have been his military genius; and I am amazed that so great a man as Carlyle, with all his hatred of shams, and his clear perceptions of justice and truth, should have whitewashed such a robber. I cannot conceive how the severest critic of the age should have spent the best years of his life in apologies for so bad a man, if his own philosophy had not become radically unsound, based on the abominable doctrine that the end justifies the means, and that an outward success is the test of right. Far different was Carlyle’s treatment of Cromwell. Frederic had no such cause as Cromwell; it was simply his own or his country’s aggrandizement by any means, or by any sword he could lay hold of. The chief merit of Carlyle’s history is his impartiality and accuracy in describing the details of the contest: the cause of the contest he does not sufficiently reprobate; and all his sympathies seem to be with the unscrupulous robber who fights heroically, rather than with indignant Europe outraged by his crimes. But we cannot separate crime from its consequences; and all the reverses, the sorrows, the perils, the hardships, the humiliations, the immense losses, the dreadful calamities through which Prussia had to pass, which wrung even the heart of Frederic with anguish, were only a merited retribution. The Seven Years’ War was a king-hunt, in which all the forces of the surrounding monarchies gathered around the doomed man, making his circle smaller and smaller, and which would certainly have ended in his utter ruin, had he not been rescued by events as unexpected as they were unparalleled. Had some great and powerful foe been converted suddenly into a friend at a critical moment, Napoleon, another unscrupulous robber, might not have been defeated at Waterloo, or died on a rock in the ocean. But Providence, it would seem, who rules the fate of war, had some inscrutable reason for the rescue of Prussia under Frederic, and the humiliation of France under Napoleon.

The brunt of the war fell of course upon Austria, so that, as the two nations were equally German, it had many of the melancholy aspects of a civil war. But Austria was Catholic and Prussia was Protestant; and had Austria succeeded, Germany possibly to-day would have been united under an irresistible Catholic imperialism, and there would have been no German empire whose capital is Berlin. The Austrians, in this contest, fought bravely and ably, under Prince Carl and Marshal Daun, who were no mean competitors with the King of Prussia for military laurels. But the Austrians fought on the offensive, and the Prussians on the defensive. The former were obliged to manoeuvre on the circumference, the latter in the centre of the circle. The Austrians, in order to recover Silesia, were compelled to cross high mountains whose passes were guarded by Prussian soldiers. The war began in offensive operations, and ended in defensive.

The most terrible enemy that Frederic had, next to Austria, was Russia, ruled then by Elizabeth, who had the deepest sympathy with Maria Theresa; but when she died, affairs took a new turn. Frederic was then on the very verge of ruin,–was, as they say, about to be “bagged,”–when the new Emperor of Russia conceived a great personal admiration for his genius and heroism; the Russian enmity was converted to friendship, and the Czar became an ally instead of a foe.

The aid which the Saxons gave to Maria Theresa availed but little. The population, chiefly and traditionally Protestant, probably sympathized with Prussia more than with Austria, although the Elector himself was Catholic,–that inglorious monarch who resembled in his gallantries Louis XV., and in his dilettante tastes Leo X. He is chiefly known for the number of his concubines and his Dresden gallery of pictures.

The aid which the French gave was really imposing, so far as numbers make efficient armies. But the French were not the warlike people in the reign of Louis XV. that they were under Henry IV., or Napoleon Bonaparte. They fought, without the stimulus of national enthusiasm, without a cause, as part of a great machine. They never have been successful in war without the inspiration of a beloved cause. This war had no especial attraction or motive for them. What was it to Frenchmen, so absorbed with themselves, whether a Hohenzollern or a Hapsburg reigned in Germany? Hence, the great armies which the government of France sent to the aid of Maria Theresa were without spirit, and were not even marshalled by able generals. In fact, the French seemed more intent on crippling England than in crushing Frederic. The war had immense complications. Though France and England were drawn into it, yet both France and England fought more against each other than for the parties who had summoned them to their rescue.

England was Frederic’s ally, but her aid was not great directly. She did not furnish him with many troops; she sent subsidies instead, which enabled him to continue the contest. But these were not as great as he expected, or had reason to expect. With all the money he received from Walpole or Pitt he was reduced to the most desperate straits.

One thing was remarkable in that long war of seven years, which strained every nerve and taxed every energy of Prussia: it was carried on by Frederic in hard cash. He did not run in debt; he’ always had enough on hand in coin to pay for all expenses. But then his subjects were most severely taxed, and the soldiers were poorly paid. If the same economy he used in that war of seven years had been exercised by our Government in its late war, we should not have had any national debt at all at the close of the war, although we probably should have suspended specie payments.

It would not be easy or interesting to attempt to compress the details of a long war of seven years in a single lecture. The records of war have great uniformity,–devastation, taxes, suffering, loss of life and of property (except by the speculators and government agents), the flight of literature, general demoralization, the lowering of the tone of moral feeling, the ascendency of unscrupulous men, the exaltation of military talents, general grief at the loss of friends, fiendish exultation over victories alternated with depressing despondency in view of defeats, the impoverishment of a nation on the whole, and the sickening conviction, which fastens on the mind after the first excitement is over, of a great waste of life and property for which there is no return, and which sometimes a whole generation cannot restore. Nothing is so dearly purchased as the laurels of the battlefield; nothing is so great a delusion and folly as military glory to the eye of a Christian or philosopher. It is purchased by the tears and blood of millions, and is rebuked by all that is grand in human progress. Only degraded and demoralized peoples can ever rejoice in war; and when it is not undertaken for a great necessity, it fills the world with bitter imprecations. It is cruel and hard and unjust in its nature, and utterly antagonistic to civilization. Its greater evils are indeed overruled; Satan is ever rebuked and baffled by a benevolent Providence. But war is always a curse and a calamity in its immediate results,–and in its ultimate results also, unless waged in defence of some immortal cause.

It must be confessed, war is terribly exciting. The eyes of the civilized world were concentrated on Frederic II. during this memorable period; and most people anticipated his overthrow. They read everywhere of his marchings and counter-marchings, his sieges and battles, his hair-breadth escapes, and his renewed exertions, from the occupation of Saxony to the battle of Torgau. In this war he was sometimes beaten, as at Kolin; but he gained three memorable victories,–one over the French, at Rossbach; the second, over the Austrians, at Luthen; and the third, over the Russians, at Zorndorf, the most bloody of all his battles. And he gained these victories by outflanking, his attack being the form of a wedge,–learned by the example of Epaminondas,–a device which led to new tactics, and proclaimed Frederic a master of the art of war. But in these battles he simply showed himself to be a great general. It was not until his reverses came that he showed himself a great man, or earned the sympathy which Europe felt for a humiliated monarch, putting forth herculean energies to save his crown and kingdom. His easy and great victories in the first year of the war simply saved him from annihilation; they were not great enough to secure peace. Although thus far he was a conqueror, he had no peace, no rest, and but little hope. His enemies were so numerous and powerful that they could send large reinforcements: he could draw but few. In time it was apparent that he would be destroyed, whatever his skill and bravery. Had not the Empress Elizabeth died, he would have been conquered and prostrated. After his defeat at Hochkirch, he was obliged to dispute his ground inch by inch, compelled to hide his grief from his soldiers, financially straitened and utterly forlorn; but for a timely subsidy from England he would have been desperate. The fatal battle of Kunnersdorf, in his fourth campaign, when he lost twenty thousand men, almost drove him to despair; and evil fortune continued to pursue him in his fifth campaign, in which he lost some of his strongest fortresses, and Silesia was opened to his enemies. At one time he had only six days’ provisions: the world marvelled how he held out. Then England deserted him. He made incredible exertions to avert his doom: everlasting marches, incessant perils; no comforts or luxuries as a king, only sorrows, privations, sufferings; enduring more labors than his soldiers; with restless anxieties and blasted hopes. In his despair and humiliation it is said he recognized God Almighty. In his chastisements and misfortunes,–apparently on the very brink of destruction, and with the piercing cries of misery which reached his ears from every corner of his dominions,–he must, at least, have recognized a Retribution. Still his indomitable will remained. His pride and his self-reliance never deserted him; he would have died rather than have yielded up Silesia until wrested from him. At last the battle of Torgau, fought in the night, and the death of the Empress of Russia, removed the overhanging clouds, and he was enabled to contend with Austria unassisted by France and Russia. But if Maria Theresa could not recover Silesia, aided by the great monarchies of Europe, what could she do without their aid? So peace came at last, when all parties were wearied and exhausted; and Frederic retained his stolen province at the sacrifice of one hundred and eighty thousand men, and the decline of one tenth of the whole population of his kingdom and its complete impoverishment, from which it did not recover for nearly one hundred years. Prussia, though a powerful military state, became and remained one of the poorest countries of Europe; and I can remember when it was rare to see there, except in the houses of the rich, either a silver fork or a silver spoon; to say nothing of the cheap and frugal fare of the great mass of the people, and their comfortless kind of life, with hardly any physical luxuries except tobacco and beer. It is surprising how, in a poor country, Frederic could have sustained such an exhaustive war without incurring a national debt. Perhaps it was not as easy in those times for kings and states to run into debt as it is now. One of the great refinements of advancing civilization is that we are permitted to bequeath our burdens to future generations. Time only will show whether this is the wisest course. It is certainly not a wise thing for individuals to do. He who enters on the possession of a heavily mortgaged estate is an embarrassed, perhaps impoverished, man. Frederic, at least, did not leave debts for posterity to pay; he preferred to pay as he went along, whatever were the difficulties.

The real gainer by the war, if gainer there was, was England, since she was enabled to establish a maritime supremacy, and develop her manufacturing and mercantile resources,–much needed in her future struggles to resist Napoleon. She also gained colonial possessions, a foothold in India, and the possession of Canada. This war entangled Europe, and led to great battles, not in Germany merely, but around the world. It was during this war, when France and England were antagonistic forces, that the military genius of Washington was first developed in America. The victories of Clive and Hastings soon after followed in India.

The greatest loser in this war was France: she lost provinces and military prestige. The war brought to light the decrepitude of the Bourbon rule. The marshals of France, with superior forces, were disgracefully defeated. The war plunged France in debt, only to be paid by a “roaring conflagration of anarchies.” The logical sequence of the war was in those discontents and taxes which prepared the way for the French Revolution,–a catastrophe or a new birth, as men differently view it.

The effect of the war on Austria was a loss of prestige, the beginning of the dismemberment of the empire, and the revelation of internal weakness. Though Maria Theresa gained general sympathy, and won great glory by her vigorous government and the heroism of her troops, she was a great loser. Besides the loss of men and money, Austria ceased to be the great threatening power of Europe. From this war England, until the close of the career of Napoleon, was really the most powerful state in Europe, and became the proudest.

As for Prussia,–the principal transgressor and actor,–it is more difficult to see the actual results. The immediate effects of the war were national impoverishment, an immense loss of life, and a fearful demoralization. The limits of the kingdom were enlarged, and its military and political power was established. It became one of the leading states of Continental Europe, surpassed only by Austria, Russia, and France. It led to great standing armies and a desire of aggrandizement. It made the army the centre of all power and the basis of social prestige. It made Frederic II. the great military hero of that age, and perpetuated his policy in Prussia. Bismarck is the sequel and sequence of Frederic. It was by aggressive and unscrupulous wars that the Romans were aggrandized, and it was also by the habits and tastes which successful war created that Rome was ultimately undermined. The Roman empire did not last like the Chinese empire, although at one period it had more glory and prestige. So war both strengthens and impoverishes nations. But I believe that the violation of eternal principles of right ultimately brings a fearful penalty. It may be long delayed, but it will finally come, as in the sequel of the wicked wars of Louis XIV. and Napoleon Bonaparte. Victor Hugo, in his “History of a Great Crime,” on the principle of everlasting justice, forewarned “Napoleon the Little” of his future reverses, while nations and kingdoms, in view of his marvellous successes, hailed him as a friend of civilization; and Hugo lived to see the fulfilment of his prophecy. Moreover, it may be urged that the Prussian people,–ground down by an absolute military despotism, the mere tools of an ambitious king,–were not responsible for the atrocious conquests of Frederic II. The misrule of monarchs does not bring permanent degradation on a nation, unless it shares the crimes of its monarch,–as in the case of the Romans, when the leading idea of the people was military conquest, from the very commencement of their state. The Prussians in the time of Frederic were a sincere, patriotic, and religious people. They were simply enslaved, and suffered the poverty and misery which were entailed by war.

After Frederic had escaped the perils of the Seven Years’ War, it is surprising he should so soon have become a party to another atrocious crime,–the division and dismemberment of Poland. But here both Russia and Austria were also participants.

“Sarmatia fell, unwept, without a crime.”

And I am still more amazed that Carlyle should cover up this crime with his sophistries. No man in ordinary life would be justified in seizing his neighbor’s property because he was weak and his property was mismanaged. We might as well justify Russia in attempting to seize Turkey, although such a crime may be overruled in the future good of Europe. But Carlyle is an Englishman; and the English seized and conquered India because they wanted it, not because they had a right to it. The same laws which bind individuals also binds kings and nations. Free nations from the obligations which bind individuals, and the world would be an anarchy. Grant that Poland was not fit for self-government, this does not justify its political annihilation. The heart of the world exclaimed against that crime at the time, and the injuries of that unfortunate state are not yet forgotten. Carlyle says the “partition of Poland was an operation of Almighty Providence and the eternal laws of Nature,”–a key to his whole philosophy, which means, if it means anything, that as great fishes swallow up the small ones, and wild beasts prey upon each other, and eagles and vultures devour other birds, it is all right for powerful nations to absorb the weak ones, as the Romans did. Might does not make right by the eternal decrees of God Almighty, written in the Bible and on the consciences of mankind. Politicians, whose primal law is expediency, may justify such acts as public robbery, for they are political Jesuits,–always were, always will be; and even calm statesmen, looking on the overruling of events, may palliate; but to enlightened Christians there is only one law, “Do unto others as ye would that they should do unto you.” Nor can Christian civilization reach an exalted plane until it is in harmony with the eternal laws of God. Mr. Carlyle glibly speaks of Almighty Providence favoring robbery; here he utters a falsehood, and I do not hesitate to say it, great as is his authority. God says, “Thou shalt not steal; Thou shalt not covet anything which is thy neighbor’s, … for he is a jealous God, visiting the sins of the fathers upon the children, to the third and fourth generation.” We must set aside the whole authority of divine revelation, to justify any crime openly or secretly committed. The prosperity of nations, in the long run, is based on righteousness; not on injustice, cruelty, and selfishness.

It cannot be denied that Frederic well managed his stolen property. He was a man of ability, of enlightened views, of indefatigable industry, and of an iron will. I would as soon deny that Cromwell did not well govern the kingdom which he had seized, on the plea of revolutionary necessity and the welfare of England, for he also was able and wise. But what was the fruit of Cromwell’s well-intended usurpation?–a hideous reaction, the return of the Stuarts, the dissipation of his visionary dreams. And if the states which Frederic seized, and the empire he had founded in blood and carnage had been as well prepared for liberty as England was, the consequences of his ambition might have been far different.

But Frederic did not so much aim at the development of national resources,–the aim of all immortal statesmen,–as at the growth and establishment of a military power. He filled his kingdom and provinces with fortresses and camps and standing armies. He cemented a military monarchy. As a wise executive ruler, the King of Prussia enforced law and order, was economical in his expenditures, and kept up a rigid discipline; even rewarded merit, and was friendly to learning. And he showed many interesting personal qualities,–for I do not wish to make him out a monster, only as a great man who did wicked things, and things which even cemented for the time the power of Prussia. He was frugal and unostentatious. Like Charlemagne, he associated with learned men. He loved music and literature; and he showed an amazing fortitude and patience in adversity, which called out universal admiration. He had a great insight into shams, was rarely imposed upon, and was scrupulous and honest in his dealings as an individual. He was also a fascinating man when he unbent; was affable, intelligent, accessible, and unstilted. He was an admirable talker, and a tolerable author. He always sympathized with intellectual excellence. He surrounded himself with great men in all departments. He had good taste and a severe dignity, and despised vulgar people; had no craving for fast horses, and held no intercourse with hostlers and gamblers, even if these gamblers had the respectable name of brokers. He punished all public thieves; so that his administration at least was dignified and respectable, and secured the respect of Europe and the admiration of men of ability. The great warrior was also a great statesman, and never made himself ridiculous, never degraded his position and powers, and could admire and detect a man of genius, even when hidden from the world. He was a Tiberius, but not a Nero fiddling over national calamities, and surrounding himself with stage-players, buffoons, and idiots.

But here his virtues ended. He was cold, selfish, dissembling, hard-hearted, ungrateful, ambitious, unscrupulous, without faith in either God or man; so sceptical in religion that he was almost an atheist. He was a disobedient son, a heartless husband, a capricious friend, and a selfish self-idolater. While he was the friend of literary men, he patronized those who were infidel in their creed. He was not a religious persecutor, because he regarded all religions as equally false and equally useful. He was social among convivial and learned friends, but cared little for women or female society. His latter years, though dignified and quiet, an idol in all military circles, with an immense fame, and surrounded with every pleasure and luxury at Sans-Souci, were still sad and gloomy, like those of most great men whose leading principle of life was vanity and egotism,–like those of Solomon, Charles V., and Louis XIV. He heard the distant rumblings, if he did not live to see the lurid fires, of the French Revolution. He had been deceived in Voltaire, but he could not mistake the logical sequence of the ideas of Rousseau,–those blasting ideas which would sweep away all feudal institutions and all irresponsible tyrannies. When Mirabeau visited him he was a quaking, suspicious, irritable, capricious, unhappy old man, though adored by his soldiers to the last,–for those were the only people he ever loved, those who were willing to die for him, those who built up his throne: and when he died, I suppose he was sincerely lamented by his army and his generals and his nobility, for with him began the greatness of Prussia as a military power. So far as a life devoted to the military and political aggrandizement of a country makes a man a patriot, Frederic the Great will receive the plaudits of those men who worship success, and who forget the enormity of unscrupulous crimes in the outward glory which immediately resulted,–yea, possibly of contemplative statesmen who see in the rise of a new power an instrument of the Almighty for some inscrutable end. To me his character and deeds have no fascination, any more than the fortunate career of some one of our modern millionnaires would have to one who took no interest in finance. It was doubtless grateful to the dying King of Prussia to hear the plaudits of his idolaters, as he stood on the hither shores of eternity; but his view of the spectators as they lined those shores must have been soon lost sight of, and their cheering and triumphant voices unheard and disregarded, as the bark, in which he sailed alone, put forth on the unknown ocean, to meet the Eternal Judge of the living and the dead.

We leave now the man who won so great a fame, to consider briefly his influence. In two respects, it seems to me, it has been decided and impressive. In the first place, he gave an impulse to rationalistic inquiries in Germany; and many there are who think this was a good thing. He made it fashionable to be cynical and doubtful. Being ashamed of his own language, and preferring the French, he encouraged the current and popular French literature, which in his day, under the guidance of Voltaire, was materialistic and deistical. He embraced a philosophy which looked to secondary rather than primal causes, which scouted any revelations that could not be explained by reason, or reconciled with scientific theories,–that false philosophy which intoxicated Franklin and Jefferson as well as Hume and Gibbon, and which finally culminated in Diderot and D’Alembert; the philosophy which became fashionable in German universities, and whose nearest approach was that of the exploded Epicureanism of the Ancients. Under the patronage of the infidel court, the universities of Germany became filled with rationalistic professors, and the pulpits with dead and formal divines; so that the glorious old Lutheranism of Prussia became the coldest and most lifeless of all the forms which Protestantism ever assumed. Doubtless, great critics and scholars arose under the stimulus of that unbounded religious speculation which the King encouraged; but they employed their learning in pulling down rather than supporting the pillars of the ancient orthodoxy. And so rapidly did rationalism spread in Northern Germany, that it changed its great lights into illuminati, who spurned what was revealed unless it was in accordance with their speculations and sweeping criticism. I need not dwell on this undisguised and blazing fact, on the rationalism which became the fashion in Germany, and which spread so disastrously over other countries, penetrating even into the inmost sanctuaries of theological instruction. All this may be progress; but to my mind it tended to extinguish the light of faith, and fill the seats of learning with cynics and unbelieving critics. It was bad enough to destroy the bodies of men in a heartless war; it was worse to nourish those principles which poisoned the soul, and spread doubt and disguised infidelities among the learned classes.

But the influence of Frederic was seen in a more marked manner in the inauguration of a national policy directed chiefly to military aggrandizement. If there ever was a purely military monarchy, it is Prussia; and this kingdom has been to Europe what Sparta was to Greece. All the successors of Frederic have followed out his policy with singular tenacity. All their habits and associations have been military. The army has been the centre of their pride, ambition, and hope. They have made their country one vast military camp. They have exempted no classes from military services; they have honored and exalted the army more than any other interest. The principal people of the land are generals. The resources of the kingdom are expended in standing armies; and these are a perpetual menace. A network of military machinery controls all other pursuits and interests. The peasant is a military slave. The student of the university can be summoned to a military camp. Precedence in rank is given to military men over merchant princes, over learned professors, over distinguished jurists. The genius of the nation has been directed to the perfection of military discipline and military weapons. The government is always prepared for war, and has been rarely averse to it. It has ever been ready to seize a province or pick a quarrel. The late war with France was as much the fault of Prussia as of the government of Napoleon. The great idea of Prussia is military aggrandizement; it is no longer a small kingdom, but a great empire, more powerful than either Austria or France. It believes in new annexations, until all Germany shall be united under a Prussian Kaiser. What Rome became, Prussia aspires to be. The spirit, the animus, of Prussia is military power. Travel in that kingdom,–everywhere are soldiers, military schools, camps, arsenals, fortresses, reviews. And this military spirit, evident during the last hundred years, has made the military classes arrogant, austere, mechanical, contemptuous. This spirit pervades the nation. It despises other nations as much as France did in the last century, or England after the wars of Napoleon.

But the great peculiarity of this military spirit is seen in the large standing armies, which dry up the resources of the nation and make war a perpetual necessity, at least a perpetual fear. It may be urged that these armies are necessary to the protection of the state,–that if they were disbanded, then France, or some other power, would arise and avenge their injuries, and cripple a state so potent to do evil. It may be so; but still the evils generated by these armies must be fatal to liberty, and antagonistic to those peaceful energies which produce the highest civilization. They are fatal to the peaceful virtues. The great Schiller has said:–

“There exists

An higher than the warrior’s excellence.

Great deeds of violence, adventures wild,

And wonders of the moment,–these are not they

Which generate the high, the blissful,

And the enduring majesty.”

I do not disdain the virtues which are developed by war; but great virtues are seldom developed by war, unless the war is stimulated by love of liberty or the conservation of immortal privileges worth more than the fortunes or the lives of men. A nation incapable of being roused in great necessities soon becomes insignificant and degenerate, like Greece when it was incorporated with the Roman empire; but I have no admiration of a nation perpetually arming and perpetually seeking political aggrandizement, when the great ends of civilization are lost sight of. And this is what Frederic sought, and his successors who cherished his ideas. The legacy he bequeathed to the world was not emancipating ideas, but the policy of military aggrandizement. And yet, has civilization no higher aim than the imitation of the ancient Romans? Can nations progressively become strong by ignoring the spirit of Christianity? Is a nation only to thrive by adopting the sentiments peculiar to robbers and bandits? I know that Prussia has not neglected education, or science, or industrial energy; but these have been made subservient to military aims. The highest civilization is that which best develops the virtues of the heart and the energies of the mind: on these the strength of man is based. It may be necessary for Prussia, in the complicated relations of governments, and in view of possible dangers, to sustain vast standing armies; but the larger these are, the more do they provoke other nations to do the same, and to eat out the vitals of national wealth. That nation is the greatest which seeks to reduce, rather than augment, forces which prey upon its resources and which are a perpetual menace. And hence the vast standing armies which conquerors seek to maintain are not an aid to civilization, but on the other hand tend to destroy it; unless by civilization and national prosperity are meant an ever-expanding policy of military aggrandizement, by which weaker and unoffending states may be gradually absorbed by irresistible despotism, like that of the Romans, whose final and logical development proves fatal to all other nationalities and liberties,–yea, to literature and art and science and industry, the extinction of which is the moral death of an empire, however grand and however boastful, only to be succeeded by new creations, through the fires of successive wars and hateful anarchies.

In one point, and one alone, I see the Providence which permitted the military aggrandizement to which Frederic and his successors aimed; and that is, in furnishing a barrier to the future conquests of a more barbarous people,–I mean the Russians; even as the conquests of Charlemagne presented a barrier to the future irruptions of barbarous tribes on his northern frontier. Russia–that rude, demoralized, Slavonic empire–cannot conquer Europe until it has first destroyed the political and military power of Germany. United and patriotic, Germany can keep at present the Russians at bay, and direct the stream of invasion to the East rather than the south; so that Europe will not become either Cossack or French, as Napoleon predicted. In this light the military genius and power of Germany, which Frederic did so much to develop, may be designed for the protection of European civilization and the Protestant religion.

But I will not speculate on the aims of Providence, or the evil to be overruled for good. With my limited vision, I can only present facts and their immediate consequences. I can only deduce the moral truths which are logically to be drawn from a career of wicked ambition. These truths are a part of that moral, wisdom which experience confirms, and which alone should be the guiding lesson to all statesmen and all empires. Let us pursue the right, and leave the consequences to Him who rules the fate of war, and guides the nations to the promised period when men shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and universal peace shall herald the reign of the Saviour of the world.

Authorities.

The great work of Carlyle on the Life of Frederic, which exhausts the subject; Macaulay’s Essay on the Life and Times of Frederic the Great; Carlyle’s Essay on Frederic; Lord Brougham on Frederic; Coxe’s History of the House of Austria; Mirabeau’s Histoire Secrète de la Cour de Berlin; Oeuvres de Frédéric le Grand; Ranke’s Neuc Bücher Preussischer Geschichte; Pöllnitz’s Memoirs and Letters; Walpole’s Reminiscences; Letters of Voltaire; Voltaire’s Idée du Roi de Prusse; Life of Baron Trenck; Gillies View of the Reign of Frederic II.; Thiebault’s Mémoires de Frédéric le Grand; Biographic Universelle; Thronbesteigung; Holden.