Jeremiah : Fall of Jerusalem – Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets

Abraham : Religious Faith

Joseph : Israel in Egypt

Moses : Jewish Jurisprudence

Samuel : Israel Under Judges

David : Israelitish Conquests

Solomon : Glory of The Monarchy

Elijah : Division of The Kingdom

Isaiah : National Degeneracy

Jeremiah : Fall of Jerusalem

Judas Maccabaeus : Restoration of The Jewish Commonwealth

Saint Paul : The Spread of Christianity

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Sadness and greatness of Jeremiah

Second as a prophet only to Isaiah

Jeremiah the Prophet of Despair

Evil days in which he was born

National misfortunes predicted

Idolatry the crying sin of the times

Discovery of the Book of Deuteronomy

Renewed study of the Law

The reforms of Josiah

The greatness of Josiah

Inability to stem prevailing wickedness

Incompleteness of Josiah’s reforms

Necho II. extends his conquests

Death of Josiah

Lamentations on the death of Josiah

Rapid decline of the kingdom

The voice of Jeremiah drowned

Invasion of Assyria by Necho

Shallum succeeds Josiah

Eliakim succeeds Shallum

His follies

Judah’s relapse into idolatry

Neglect of the Sabbath

Jeremiah announces approaching calamity

His voice unheeded

His despondency

Fall of Nineveh

Defeat and retreat of Necho

Greatness of Nebuchadnezzar

Appears before Jerusalem

Fall of Jerusalem, but destruction delayed

Folly and infatuation of the people of Jerusalem

Revolt of the city

Zedekiah the king temporizes

Expostulations of Jeremiah

Nebuchadnezzar loses patience

Second fall of Jerusalem

The captivity

Weeping by the river of Babylon

Jeremiah : Fall of Jerusalem

ABOUT 629-580 B.C.

Jeremiah is a study to those who would know the history of the latter days of the Jewish monarchy, before it finally succumbed to the Babylonian conqueror. He was a sad and isolated man, who uttered his prophetic warnings to a perverse and scornful generation; persecuted because he was truthful, yet not entirely neglected or disregarded, since he was consulted in great national dangers by the monarchs with whom he was contemporary. So important were his utterances, it is matter of great satisfaction that they were committed to writing, for the benefit of future generations,–not of Jews only, but of the Gentiles,–on account of the fundamental truths contained in them. Next to Isaiah, Jeremiah was the most prominent of the prophets who were commissioned to declare the will and judgments of Jehovah on a degenerate and backsliding people. He was a preacher of righteousness, as well as a prophet of impending woes. As a reformer he was unsuccessful, since the Hebrew nation was incorrigibly joined to its idols. His public career extended over a period of forty years. He was neither popular with the people, nor a favorite of kings and princes; the nation was against him and the times were against him. He exasperated alike the priests, the nobles, and the populace by his rebukes. As a prophet he had no honor in his native place. He uniformly opposed the current of popular prejudices, and denounced every form of selfishness and superstition; but all his protests and rebukes were in vain. There were very few to encourage him or comfort him. Like Noah, he was alone amidst universal derision and scorn, so that he was sad beyond measure, more filled with grief than with indignation.

Jeremiah was not bold and stern, like Elijah, but retiring, plaintive, mournful, tender. As he surveyed the downward descent of Judah, which nothing apparently could arrest, he exclaimed: “Oh that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the daughter of my people!” Is it possible for language to express a deeper despondency, or a more tender grief? Pathos and unselfishness are blended with his despair. It is not for himself that he is overwhelmed with gloom, but for the sins of the people. It is because the people would not hear, would not consider, and would persist in their folly and wickedness, that grief pierces his soul. He weeps for them, as Christ wept over Jerusalem. Yet at times he is stung into bitter imprecations, he becomes fierce and impatient; and then again he rises over the gloom which envelops him, in the conviction that there will be a new covenant between God and man, after the punishment for sin shall have been inflicted. But his prevailing feelings are grief and despair, since he has no hopes of national reform. So he predicts woes and calamities at no distant day, which are to be so overwhelming that his soul is crushed in the anticipation of them. He cannot laugh, he cannot rejoice, he cannot sing, he cannot eat and drink like other men. He seeks solitude; he longs for the desert; he abstains from marriage, he is ascetic in all his ways; he sits alone and keeps silence, and communes only with his God; and when forced into the streets and courts of the city, it is only with the faint hope that he may find an honest man. No persons command his respect save the Arabian Rechabites, who have the austere habits of the wilderness, like those of the early Syrian monks. Yet his gloom is different from theirs: they seek to avert divine wrath for their own sins; he sees this wrath about to descend for the sins of others, and overwhelm the whole nation in misery and shame.

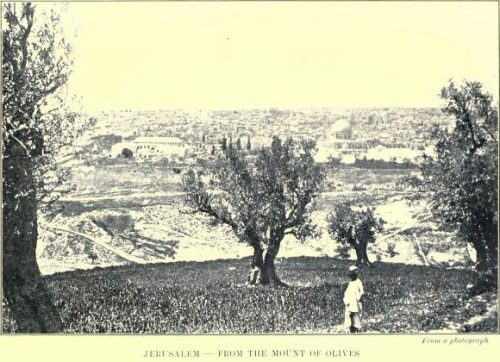

Jeremiah was born in the little ecclesiastical town of Anathoth, about three miles from Jerusalem, and was the son of a priest. We do not know the exact year of his birth, but he was a very young man when he received his divine commission as a prophet, about six hundred and twenty-seven years before Christ. Josiah had then been on the throne of Judah twelve years. The kingdom was apparently prosperous, and was unmolested by external enemies. For seventy-five years Assyria had given but little trouble, and Egypt was occupied with the siege of Ashdod, which had been going on for twenty-nine years, so strong was that Philistine city. But in the absence of external dangers corruption, following wealth, was making fearful strides among the people, and impiety was nearly universal. Every one was bent on pleasure or gain, and prophet and priest were worldly and deceitful. From the time when Jeremiah was first called to the prophetic office until the fall of Jerusalem there was an unbroken series of national misfortunes, gradually darkening into utter ruin and exile. He may have shrunk from the perils and mortifications which attended him for forty years, as his nature was sensitive and tender; but during this long ministry he was incessant in his labors, lifting up his voice in the courts of the Temple, in the palace of the king, in prison, in private houses, in the country around Jerusalem. The burden of his utterances was a denunciation of idolatry, and a lamentation over its consequences. “My people, saith Jehovah, have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewn out for themselves underground cisterns, full of rents, that can hold no water…. Behold, O Judah! thou shalt be brought to shame by thy new alliance with Egypt, as thou wast in the past by thy old alliance with Assyria.”

In this denunciation by the prophet we see that he mingled in political affairs, and opposed the alliance which Judah made with Egypt, which ever proved a broken reed. Egypt was a vain support against the new power that was rising on the Euphrates, carrying all before it, even to the destruction of Nineveh, and was threatening Damascus and Tyre as well as Jerusalem. The power which Judah had now to fear was Babylon, not Assyria. If any alliance was to be formed, it was better to conciliate Babylon than Egypt.

Roused by the earnest eloquence of Jeremiah, and of those of the group of earnest followers of Jehovah who stood with him,–Huldah the prophetess, Shallum her husband, keeper of the royal wardrobe, Hilkiah the high-priest, and Shaphan the scribe, or secretary,–the youthful king Josiah, in the eighteenth year of his reign, when he was himself but twenty-six years old, set about reforms, which the nobles and priests bitterly opposed. Idolatry had been the fashionable religion for nearly seventy years, and the Law was nearly forgotten. The corruption of the priesthood and of the great body of the prophets kept pace with the degeneracy of the people. The Temple was dilapidated, and its gold and bronze decorations had been despoiled. The king undertook a thorough repair of the great Sanctuary, and during its progress a discovery was made by the high-priest Hilkiah of a copy of the Law, hidden amid the rubbish of one of the cells or chambers of the Temple. It is generally supposed to have been the Book of Deuteronomy. When it was lost, and how, it is not easy to ascertain,–probably during the reign of some one of the idolatrous kings. It seems to have been entirely forgotten,–a proof of the general apostasy of the nation. But the discovery of the book was hailed by Josiah as a very important event; and its effect was to give a renewed impetus to his reforms, and a renewed study of patriarchal history. He forthwith assembled the leading men of the nation,–prophets, priests, Levites, nobles, and heads of tribes. He read to them the details of the ancient covenant, and solemnly declared his purpose to keep the commandments and statutes of Jehovah as laid down in the precious book. The assembled elders and priests gave their eager concurrence to the act of the king, and Judah once more, outwardly at least, became the people of God.

Nor can it be questioned that the renewed study of the Law, as brought about by Josiah, produced a great influence on the future of the Hebrew nation, especially in the renunciation of idolatry. Yet this reform, great as it was, did not prevent the fall of Jerusalem and the exile of the leading people among the Hebrews to the land of the Chaldeans, whence Abraham their great progenitor had emigrated.

Josiah, who was thoroughly aroused by “the words of the book,” and its denunciations of the wrath of Jehovah upon the people if they should forsake his ways, in spite of the secret opposition of the nobles and priests, zealously pursued the work of reform. The “high places,” on which were heathen altars, were levelled with the ground; the images of the gods were overthrown; the Temple was purified, and the abominations which had disgraced it were removed. His reforms extended even to the scattered population of Samaria whom the Assyrians had spared, and all the buildings connected with the worship of Baal and Astaroth at Bethel were destroyed. Their very stones were broken in pieces, under the eyes of Josiah himself. The skeletons of the pagan priests were dragged from their burial places and burned.

An elaborate celebration of the feast of the Passover followed soon after the discovery of the copy of the Law, whether confined to Deuteronomy or including other additional writings ascribed to Moses, we know not. This great Passover was the leading internal event of the reign of Josiah. Having “taken away all the abominations out of all the countries that belonged to the children of Israel,” even as the earlier keepers of the Law cleansed their premises, especially of all remains of leaven,–the symbol of corruption,–the king commanded a celebration of the feast of deliverance. Priests and Levites were sent throughout the country to instruct the people in the preparations demanded for the Passover. The sacred ark, hidden during the reigns of Manasseh and Amon, was restored to its old place in the Temple, where it remained until the Temple was destroyed. On the approach of the festival, which was to be held with unusual solemnities, great multitudes from all parts of Palestine assembled at Jerusalem, and three thousand bullocks and thirty thousand lambs were provided by the king for the seven days’ feast which followed the Passover. The princes also added eight hundred oxen and seven thousand six hundred small cattle as a gift to priests and people. After the priests in their white robes, with bare feet and uncovered heads, and the Levites at their side according to the king’s commandment, had “killed the passover” and “sprinkled the blood from their hands,” each Levite having first washed himself in the Temple laver, the part of the animal required for the burnt-offering was laid on the altar flames, and the remainder was cooked by the Levites for the people, either baked, roasted, or boiled. And this continued for seven days; during all the while the services of the Temple choir were conducted by the singers, chanting the psalms of David and of Asaph. Such a Passover had not been held since the days of Samuel. No king, not even David or Solomon, had celebrated the festival on so grand a scale. The minutest details of the requirements of the Law were attended to. The festival proclaimed the full restoration of the worship of Jehovah, and kindled enthusiasm for his service. So great was this event that Ezekiel dates the opening of his prophecies from it. “It seems probable that we have in the eighty-fifth psalm a relic of this great solemnity…. Its tone is sad amidst all the great public rejoicings; it bewails the stubborn ungodliness of the people as a whole.”

After the great Passover, which took place in the year 622, when Josiah was twenty-six years of age, little is said of the pious king, who reigned twelve years after this memorable event. One of the best, though not one of the wisest, kings of Judah, he did his best to eradicate every trace of idolatry; but the hearts of the people responded faintly to his efforts. Reform was only outward and superficial,–an illustration of the inability even of an absolute monarch to remove evils to which the people cling in their hearts. To the eyes of Jeremiah, there was no hope while the hearts of the people were unchanged. “Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?” he mournfully exclaims. “Much less can those who are accustomed to do evil learn to do well.” He had no illusions; he saw the true state of affairs, and was not misled by mere outward and enforced reforms, which partook of the nature of religious persecution, and irritated the people rather than led to a true religious life among them. There was nothing left to him but to declare woes and approaching calamities, to which the people were insensible. They mocked and reviled him. His lofty position secured him a hearing, but he preached to stones. The people believed nothing but lies; many were indifferent and some were secretly hostile, and he must have been pained and disappointed in view of the incompleteness of his work through the secret opposition of the popular leaders.

Josiah was the most virtuous monarch of Judah. It was a great public misfortune that his life was cut short prematurely at the age of thirty-eight, and in consequence of his own imprudence. He undertook to oppose the encroachments of Necho II, king of Egypt, an able, warlike, and enterprising monarch, distinguished for his naval expeditions, whose ships doubled the Cape of Good Hope, and returned to Egypt in safety, after a three years’ voyage. Necho was not so successful in digging a canal across the Isthmus of Suez, in which enterprise one hundred and twenty thousand men perished from hunger, fatigue, and disease. But his great aim was to extend his empire to the limits reached by Rameses II., the Sesostris of the Greeks. The great Assyrian empire was then breaking up, and Nineveh was about to fall before the Babylonians; so he seized the opportunity to invade Syria, a province of the Assyrian empire. He must of course pass through Palestine, the great highway between Egypt and the East. Josiah opposed his enterprise, fearing that if the Egyptian king conquered Syria, he himself would become the vassal of Egypt. Jeremiah earnestly endeavored to dissuade his sovereign from embarking in so doubtful a war; even Necho tried to convince him through his envoys that he made war on Nineveh, not on Jerusalem, invoking–as most intensely earnest men did in those days of tremendous impulse–the sacred name of Deity as his authentication. Said he: “What have I to do with thee, thou King of Judah? I come not against thee this day, but against the house wherewith I have war; for God commanded me to make haste. Forbear thee from meddling with God, who is with me, that he destroy thee not.” But nothing could induce Josiah to give up his warlike enterprise. He had the piety of Saint Louis, and also his patriotic and chivalric heroism. He marched his forces to the plain of Esdraelon, the great battle field where Rameses II. had triumphed over the Hittites centuries before. The battle was fought at Megiddo. Although Josiah took the precaution to disguise himself, he was mortally wounded by the Egyptian archers, and was driven back in his splendid chariot toward Jerusalem, which he did not live to reach.

The lamentations for this brave and pious monarch remind us of the universal grief of the Hebrew nation on the death of Samuel. He was buried in a tomb which he had prepared for himself, amid universal mourning. A funeral oration was composed by Jeremiah, or rather an elegy, afterward sung by the nation on the anniversary of the battle. Nor did the nation ever forget a king so virtuous in his life and so zealous for the Law. Long after the return from captivity the singers of Israel sang his praises, and popular veneration for him increased with the lapse of time; for in virtues and piety, and uninterrupted zeal for Jehovah, Josiah never had an equal among the kings of Judah.

The services of this good king were long remembered. To him may be traced the unyielding devotion of the Jews, after the Captivity, for the rites and forms and ceremonies which are found in the books of the Law. The legalisms of the Scribes may be traced to him. He reigned but twelve years after his great reformation,–not long enough to root out the heathenism which had prevailed unchecked for nearly seventy years. With him perished the hopes of the kingdom.

After his death the decline was rapid. A great reaction set in, and faction was accompanied with violence. The heathen party triumphed over the orthodox party. The passions which had been suppressed since the death of Manasseh burst out with all the frenzy and savage hatred which have ever marked the Jews in their religious contentions, and these were unrestrained by the four kings who succeeded Josiah. The people were devoured by religious animosities, and split up into hostile factions. Had the nation been united, it is possible that later it might have successfully resisted the armies of Nebuchadnezzar. Jeremiah gave vent to his despairing sentiments, and held out no hope. When Elijah had appealed to the people to choose between Jehovah and Baal, he was successful, because they were then undecided and wavering in their belief, and it required only an evidence of superior power to bring them back to their allegiance. But when Jeremiah appeared, idolatry was the popular religion. It had become so firmly established by a succession of wicked kings, added to the universal degeneracy, that even Josiah could work but a temporary reform.

Hence the voice of Jeremiah was drowned. Even the prophets of his day had become men of the world. They fawned on the rich and powerful whose favor they sought, and prophesied “smooth things” to them. They were the optimists of a decaying nation and a godless, pleasure-seeking generation. They were to Jerusalem what the Sophists were to Athens when Demosthenes thundered his disregarded warnings. There were, indeed, a few prophets left who labored for the truth; but their words fell on listless ears. Nor could the priests arrest the ruin, for they were as corrupt as the people. The most learned among them were zealous only for the letter of the law, and fostered among the people a hypocritical formalism. True religious life had departed; and the noble Jeremiah, the only great statesman as well as prophet who remained, saw his influence progressively declining, until at last he was utterly disregarded. Yet he maintained his dignity, and fearlessly declared his message.

In the meantime the triumphant Necho, after the defeat and dispersion of Josiah’s army, pursued his way toward Damascus, which he at once overpowered. From thence he invaded Assyria, and stripped Nineveh of its most fertile provinces. The capital itself was besieged by Nabopolassar and Cyaxares the Mede, and Necho was left for a time in possession of his newly-acquired dominion.

Josiah was succeeded by his son Shallum, who assumed the crown under the name of Jehoaz, which event it seems gave umbrage to the king of Egypt. So he despatched an army to Jerusalem, which yielded at once, and King Jehoaz was sent as a captive to the banks of the Nile. His elder brother Eliakim was appointed king in his place, under the name of Jehoiakim, who thus became the vassal of Necho. He was a young man of twenty-five, self-indulgent, proud, despotic, and extravagant. There could be no more impressive comment on the infatuation and folly of the times than the embellishment of Jerusalem with palaces and public buildings, with the view to imitate the glory of Solomon. In everything the king differed from his father Josiah, especially in his treatment of Jeremiah, whom he would have killed. He headed the movement to restore paganism; altars were erected on every hill to heathen deities, so that there were more gods in Judah than there were towns. Even the sacred animals of Egypt were worshipped in the dark chambers beneath the Temple. In the most sacred places of the Temple itself idolatrous priests worshipped the rising sun, and the obscene rites of Phoenician idolatry were performed in private houses. The decline in morals kept pace with the decline of spiritual religion. There was no vice which was not rampant throughout the land,–adultery, oppression of foreigners, venality in judges, falsehood, dishonesty in trade, usury, cruelty to debtors, robbery and murder, the loosing of the ties of kindred, general suspicion of neighbors,–all the crimes enumerated by the Apostle Paul among the Romans. Judah in reality had become an idolatrous nation like Tyre and Syria and Egypt, with only here and there a witness to the truth, like Jeremiah, the prophetess Huldah, and Baruch the scribe.

This relapse into heathenism filled the soul of Jeremiah with grief and indignation, but gave to him a courage foreign to his timid and shrinking nature. In the presence of the king, the princes, and priests he was defiant, immovable, and fearless, uttering his solemn warnings from day to day with noble fidelity. All classes turned against him; the nobles were furious at his exposure of their license and robberies, the priests hated him for his denunciation of hypocrisy, and the people for his gloomy prophecies that the Temple should be destroyed, Jerusalem reduced to ashes, and they themselves led into captivity.

Not only were crime and idolatry rampant, but the death of Josiah was followed by droughts and famine. In vain were the prayers of Jeremiah to avert calamity. Jehovah replied to him: “Pray not for this people! Though they fast, I will not hear their cry; though they offer sacrifice I have no pleasure in them, but will consume them by the sword, by famine, and pestilence.” Jeremiah piteously gives way to despairing lamentations. “Hast thou, O Lord, utterly rejected Judah? Is thy soul tired of Zion? Why hast thou smitten us so that there is no healing for us?” Jehovah replies: “If Moses and Samuel stood pleading before me, my soul could not be toward this people. I appoint four destroyers,–the sword to slay, the dogs to tear and fight over the corpse, the birds of the air, and the beasts of the field; for who will have pity on thee, O Jerusalem? Thou hast rejected me. I am weary of relenting. I will scatter them as with a broad winnowing-shovel, as men scatter the chaff on the threshing-floor.”

Such, amid general depravity and derision, were some of the utterances of the prophet, during the reign of Jehoiakim. Among other evils which he denounced was the neglect of the Sabbath, so faithfully observed in earlier and better times. At the gates of the city he cried aloud against the general profanation of the sacred day, which instead of being a day of rest was the busiest day of the week, when the city was like a great fair and holiday. On this day the people of the neighboring villages brought for sale their figs and grapes and wine and vegetables; on this day the wine-presses were trodden in the country, and the harvest was carried to the threshing-floors. The preacher made himself especially odious for his rebuke for the violation of the Sabbath. “Come,” said his enemies to the crowd, “let us lay a plot against him; let us smite him with the tongue by reporting his words to the king, and bearing false witness against him.” On this renewed persecution the prophet does not as usual give way to lamentation, but hurls his maledictions. “O Jehovah! give thou their sons to hunger, deliver them to the sword; let their wives be made childless and widows; let their strong men be given over to death, and their young men be smitten with the sword.”

And to consummate, as it were, his threats of divine punishment so soon to be visited on the degenerate city, Jeremiah is directed to buy an earthenware bottle, such as was used by the peasants to hold their drinking-water, and to summon the elders and priests of Jerusalem to the southwestern corner of the city, and to throw before their feet the bottle and shiver it in pieces, as a significant symbol of the approaching fall of the city, to be destroyed as utterly as the shattered jar. “And I will empty out in the dust, says Jehovah, the counsels of Judah and Jerusalem, as this water is now poured from the bottle. And I will cause them to fall by the sword before their enemies and by the hands of those that seek their lives; and I will give their corpses for meat to the birds of heaven and the beasts of the earth; and I will make this city an astonishment and a scoffing. Every one that passes by it will be astonished and hiss at its misfortunes. Even so will I shatter this people and this city, as this bottle, which cannot be made whole again, has been shattered.” Nor was Jeremiah contented to utter these fearful maledictions to the priests and elders; he made his way to the Temple, and taking his stand among the people, he reiterated, amid a storm of hisses, mockeries, and threats, what he had just declared to a smaller audience in reference to Jerusalem.

Such an appalling announcement of calamities, and in such strong and plain language, must have transported his hearers with fear or with wrath. He was either the ambassador of Heaven, before whose voice the people in the time of Elijah would have quaked with unutterable anguish, or a madman who was no longer to be endured. We have no record of any prophet or any preacher who ever used language so terrible or so daring. Even Luther never hurled such maledictions on the church which he called the “scarlet mother.” Jeremiah uttered no vague generalities, but brought the matter home with awful directness. Among his auditors was Pashur, the chief governor of the Temple, and a priest by birth. He at once ordered the Temple police to seize the bold and outspoken prophet, who was forthwith punished for his plain speaking by the bastinado, and then hurried bleeding to the stocks, into which his head and feet and hands were rudely thrust, to spend the night amid the jeers of the crowd and the cold dews of the season. In the morning he was set free, his enemies thinking that he now would hold his tongue; but Jeremiah, so far from keeping silence, renewed his threats of divine vengeance. “For thus saith Jehovah, I will give all Judah into the hands of the king of Babylon, and he shall carry them captive to Babylon, and slay them with the sword.” And then turning to Pashur, before the astonished attendants, he exclaimed: “And thou, Pashur, and all that dwell in thy house, will be dragged off into captivity; and thou wilt come to Babylon, and thou wilt die and be buried there,–thou and all thy partisans to whom thou hast prophesied lies.”

We observe in these angry words of Jeremiah great directness and great minuteness, so that his meaning could not be mistaken; also that the instrument of punishment on the degenerate and godless city was to be the king of Babylon, a new power from whom Judah as yet had received no harm. The old enemies of the Hebrews were the Assyrians and Egyptians, not the Babylonians and Medes.

Whatever may have been the malignant animosity of Pashur, he was evidently afraid to molest the awful prophet and preacher any further, for Jeremiah was no insignificant person at Jerusalem. He was not only recognized as a prophet of Jehovah, but he had been the friend and counsellor of King Josiah, and was the leading statesman of the day in the ranks of the opposition. But distinguished as he was, his voice was disregarded, and he was probably looked upon as an old croaker, whose gloomy views had no reason to sustain them. Was not Jerusalem strong in her defences, and impregnable in the eyes of the people; and was she not regarded as under the special protection of the Deity? Suppose some austere priest–say such a man as the Abbé Lacordaire–had risen from the pulpit of Notre Dame or the Madeleine, a year before the battle of Sedan, and announced to the fashionable congregation assembled to hear his eloquence, and among them the ministers of Louis Napoleon, that in a short time Paris would be surrounded by conquering armies, and would endure all the horrors of a siege, and that the famine would be so great that the city would surrender and be at the entire mercy of the conquerors,–would he have been believed? Would not the people have regarded him as a madman, great as was his eloquence, or as the most gloomy of pessimists, for whom they would have felt contempt or bitter wrath? And had he added to his predictions of ruin, utterly inconceivable by the giddy, pleasure-seeking, atheistic people, the most scathing denunciations of the prevailing sins of that godless city, all the more powerful because they were true, addressed to all classes alike, positive, direct, bold, without favor and without fear,–would they not have been stirred to violence, and subjected him to any chastisement in their power? If Socrates, by provoking questions and fearless irony, drove the Athenians to such wrath that they took his life, even when everybody knew that he was the greatest and best man at Athens, how much more savage and malignant must have been the narrow-minded Jews when Jeremiah laid bare to them their sins and the impotency of their gods, and the certainty of retribution!

Yet vehement, or direct, or plain as were Jeremiah’s denunciations to the idol-worshippers of Jerusalem in the seventh century before it was finally destroyed by Titus, he was no more severe than when Jesus denounced the hypocrisy of the Scribes and Pharisees, no more mournful than when he lamented over the approaching ruin of the Temple. Therefore they sought to kill him, as the princes and priests of Judah would have sacrificed the greatest prophet that had appeared since Elisha, the greatest statesman since Samuel, the greatest poet since David, if Isaiah alone be excepted. No wonder he was driven to a state of despondency and grief that reminds us of Job upon his ash-heap. “Cursed be the day,” he exclaims, in his lonely chamber, “on which I was born! Cursed be the man who brought tidings to my father, saying, A man-child is born to thee, making him very glad! Why did I come forth from the womb that my days might be spent in shame?” A great and good man may be urged by the sense of duty to declare truths which he knows will lead to martyrdom; but no martyr was ever insensible to suffering or shame. All the glories of his future crown cannot sweeten the bitterness of the cup he is compelled to drain; even the greatest of martyrs prayed in his agony that the cup might pass from him. How could a man help being sad and even bitter, if ever so exalted in soul, when he saw that his warnings were utterly disregarded, and that no mortal influence or power could avert the doom he was compelled to pronounce as an ambassador of God? And when in addition to his grief as a patriot he was unjustly made to suffer reproach, scourgings, imprisonment, and probable death, how can we wonder that his patience was exhausted? He felt as if a burning fire consumed his very bones, and he could refrain no longer. He cried aloud in the intensity of his grief and pain, and Jehovah, in whom he trusted, appeared to him as a mighty champion and an everlasting support.

Jeremiah at this time, during the early years of the reign of Jehoiakim, the period of the most active part of his ministry, was about forty-five years of age. Great events were then taking place. Nineveh was besieged by one of its former generals,–Nabopolassar, now king of Babylon. The siege lasted two years, and the city fell in the year 606 B.C., when Jehoiakim had been about four years on the throne. The fall of this great capital enabled the son of the king of Babylonia, Nebuchadnezzar, to advance against Necho, the king of Egypt, who had taken Carchemish about three years before. Near that ancient capital of the Hittites, on the banks of the Euphrates, one of the most important battles of antiquity was fought,–and Necho, whose armies a few years before had so successfully invaded the Assyrian empire, was forced to retreat to Egypt. The battle of Carchemish put an end to Egyptian conquests in the East, and enabled the young sovereign of Babylonia to attain a power and elevation such as no Oriental monarch had ever before enjoyed. Babylon became the centre of a new empire, which embraced the countries that had bowed down to the Assyrian yoke. Nebuchadnezzar in the pride of victory now meditated the conquest of Egypt, and must needs pass through Palestine. But Jehoiakim was a vassal of Egypt, and had probably furnished troops for Necho at the fatal battle of Carchemish. Of course the Babylonian monarch would invade Judah on his way to Egypt, and punish its king, whom he could only look upon as an enemy.

It was then that Jeremiah, sad and desponding over the fate of Jerusalem, which he knew was doomed, committed his precious utterances to writing by the assistance of his friend and companion Baruch. He had lately been living in retirement, feeling that his message was delivered; possibly he feared that the king would put him to death as he had the prophet Urijah. But he wished to make one more attempt to call the people to repentance, as the only way to escape impending calamities; and he prevailed upon his secretary to read the scroll, containing all his verbal utterances, to the assembled people in the Temple, who, in view of their political dangers, were celebrating a solemn fast. The priests and people alike, clad in black hair-cloth mantles, with ashes on their heads, lay prostrate on the ground, and by numerous sacrifices hoped to propitiate the Deity. But not by sacrifices and fasts were they to be saved from Nebuchadnezzar’s army, as Jeremiah had foretold years before. The recital by Baruch of the calamities he had predicted made a profound impression on the crowd. A young man, awed by what he had heard, hastened to the hall in which the princes were assembled, and told them what had been read from the prophet’s scroll. They in their turn were alarmed, and commanded Baruch to read the contents to them also. So intense was the excitement that the matter was laid before the king, who ordered the roll to be read to him: he would hear the words that Jeremiah had caused to be written down. But scarcely had the reading of the roll begun before he flew into a violent rage, and seizing the manuscript he cut it to pieces with the scribe’s knife, and burned it upon a brazier of coals. Orders were instantly given to arrest both Jeremiah and Baruch; but they had been warned and fled, and the place of their concealment could not be found.

Jehoiakim thus rejected the last offer of mercy with scorn and anger, although many of his officers were filled with fear. His heart was hardened, like that of Pharaoh before Moses. Jeremiah having learned the fate of the roll, dictated its contents anew to his faithful secretary, and a second roll was preserved, not, however, without contriving to send to the king this awful message. “Thus saith Jehovah of thee Jehoiakim: He shall have no son to sit on the throne of David, and his dead body will be cast out to lie in the heat by day and the frost by night; and no one shall raise a lament for him when he dies. He shall be buried with the burial of an ass, drawn out of Jerusalem, and cast down from its gates.”

No wonder that we lose sight of Jeremiah during the remainder of the reign of Jehoiakim; it was not safe for him to appear anywhere in public. For a time his voice was not heard; yet his predictions had such weight that the king dared not defy Nebuchadnezzar when he demanded the submission of Jerusalem. He was forced to become the vassal of the king of Babylonia, and furnish a contingent to his army. But this vassalage bore heavily on the arrogant soul of Jehoiakim, and he seized the first occasion to rebel, especially as Necho promised him protection. This rebellion was suicidal and fatal, since Babylon was the stronger power. Nebuchadnezzar, after the three years of forced submission, appeared before the gates of Jerusalem with an irresistible army. There was no resistance, as resistance was folly. Jehoiakim was put in chains, and avoided being carried captive to Babylon only by the most abject submission to the conqueror. All that was valuable in the Temple and the palaces was seized as spoil. Jerusalem was spared for a while; and in the mean time Jehoiakim died, and so intensely was he hated and despised that no dirge was sung over his remains, while his dishonored body was thrown outside the walls of his capital like that of a dead ass, as Jeremiah had foretold.

On his death, B.C. 598, after a reign of eight years, his son Jehoiachin, at the age of eighteen, ascended his nominal throne. He also, like his father, followed the lead of the heathen party. The bitterness of the Babylonian rule, united with the intrigues of Egypt, led to a fresh revolt, and Jerusalem was invested by a powerful Chaldean army.

Jeremiah now appears again upon the stage, but only to reaffirm the calamities which impended over his nation,–all of which he traced to the decay of religion and morality. The mission and the work of the Jews were to keep alive the worship of the One God amid universal idolatry. Outside of this, they were nothing as a nation. They numbered only four or five millions of people, and lived in a country not much larger than one of the northern counties of England and smaller than the state of New Hampshire or Vermont; they gave no impulse to art or science. Yet as the guardians of the central theme of the only true religion and of the sacred literature of the Bible, their history is an important link in the world’s history. Take away the only thing which made them an object of divine favor, and they were of no more account than Hittites, or Moabites, or Philistines. The chosen people had become idolatrous like the surrounding nations, hopelessly degenerate and wicked, and they were to receive a dreadful chastisement as the only way by which they would return to the One God, and thus act their appointed part in the great drama of humanity. Jeremiah predicted this chastisement. The chosen people were to suffer a seventy years’ captivity, and then city and Temple were to be destroyed. But Jeremiah, sad as he was over the fate of his nation, and terribly severe as he was in his denunciations of the national sins, knew that his people would repent by the river of Babylon, and be finally restored to their old inheritance. Yet nothing could avert their punishment.

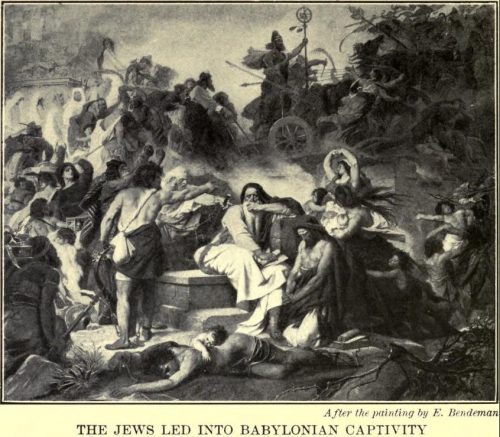

In less than three months after Jehoiachin became king of Judah, its capital was unconditionally surrendered to the Chaldean hosts, since resistance was vain. No pity was shown to the rebels, though the king and nobles had appeared before Nebuchadnezzar with every mark and emblem of humiliation and submission. The king and his court and his wives, and all the principal people of the nation, were sent to Babylon as captives and slaves. The prompt capitulation saved the city for a time from complete destruction; but its glory was turned to shame and grief. All that was of any value in the Temple and city was carried to the banks of the Euphrates, nearly one hundred and fifty years after Samaria had fallen from a protracted siege, and its inhabitants finally dispersed among the nations that were subject to Nineveh.

One would suppose that after so great a calamity the few remaining people in Jerusalem and in the desolate villages of Judah would have given no further molestation to their powerful and triumphant enemies. The land was exhausted; the towns were stripped of their fighting population, and only the shadow of a kingdom remained. Instead of appointing a governor from his own court over the conquered province, Nebuchadnezzar gave the government into the hands of Mattaniah, the third son of Josiah, a youth of twenty, changing his name to Zedekiah. He was for a time faithful to his allegiance, and took much pains to quiet the mind of the powerful sovereign who ruled the Eastern world, and even made a journey to Babylon to pay his homage. He was a weak prince, however, alternately swayed by the different parties,–those that counselled resistance to Babylon, and those, like Jeremiah, that advised submission. This long-headed statesman saw clearly that rebellion against Nebuchadnezzar, flushed with victory, and with the whole Eastern world at his feet, was absurd; but that the time would come when Babylon in turn should be humbled, and then the captive Hebrews would probably return to their own land, made wiser by their captivity of seventy years. The other party, leagued with Moabites, Tyrians, Egyptians, and other nations, thought themselves strong enough to break their allegiance to Nebuchadnezzar; and bitter were the contentions of these parties. Jeremiah had great influence with the king, who was weak rather than wicked, and had his counsels been consistently followed, Jerusalem would probably have been spared, and the Temple would, have remained. He preferred vassalage to utter ruin. With Babylon pressing on one side and Egypt on the other,–both great monarchies,–vassalage to one or the other of these powers was inevitable. Indeed, vassalage had been the unhappy condition of Judah since the death of Josiah. Of the two powers Jeremiah preferred the Chaldean rule, and persistently advised submission to it, as the only way to save Jerusalem from utter destruction.

Unfortunately Zedekiah temporized; he courted all parties in turn, and listened to the schemes of rebellion,–for all the nations of Palestine were either conquered or invaded by the Chaldeans, and wished to shake off the yoke. Nebuchadnezzar lost faith in Zedekiah; and being irritated by his intrigues, he resolved to attack Jerusalem while he was conducting the siege of Tyre and fighting with Egypt, a rival power. Jerusalem was in his way. It was a small city, but it gave him annoyance, and he resolved to crush it. It was to him what Tyre became to Alexander in his conquests. It lay between him and Egypt, and might be dangerous by its alliances. It was a strong citadel which he had unwisely spared, but determined to spare no longer.

The suspicions of the king of Babylonia were probably increased by the disaffection of the Jewish exiles themselves, who believed in the overthrow of Nebuchadnezzar and their own speedy return to their native hills. A joint embassy was sent from Edom, from Moab, the Ammonites, and the kings of Tyre and Sidon, to Jerusalem, with the hope that Zedekiah would unite with them in shaking off the Babylonian yoke; and these intrigues were encouraged by Egypt. Jeremiah, who foresaw the consequences of all this, earnestly protested. And to make his protest more forcible, he procured a number of common ox-yokes, and having put one on his own neck while the embassy was in the city, he sent one to each of the envoys, with the following message to their masters: “Thus saith Jehovah, the God of Israel. I have made the earth and man and the beasts on the face of the earth by my great power, and I give it to whom I see fit. And now I have given all these lands into the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, to serve him. And all nations shall serve him, till the time of his own land comes; and then many nations and great kings shall make him their servant. And the nation and people that will not serve him, and that does not give its own neck to the yoke, that nation I will punish with sword, famine, and pestilence, till I have consumed them by his hand.” A similar message he sent to Zedekiah and the princes who seemed to have influenced him. “Bring your necks under the yoke of the king of Babylon, and serve him, and ye shall live. Do not listen to the words of the prophets who say to you, Ye shall not serve the king of Babylon. They prophesy a lie to you.” The same message in substance he sent to the priests and people, urging them not to listen to the voice of the false prophets, who based their opinions on the anticipated interference of God to save Jerusalem from destruction; for that destruction would surely come if its people did not serve the king of Babylonia until the appointed time should come, when Babylon itself should fall into the hands of enemies more powerful than itself, even the Medes and Persians.

Jeremiah, thus brought into direct opposition to the false prophets, was exposed to their bitterest wrath. But he was undaunted, although alone, and thus boldly addressed Hananiah, one of their leaders and himself a priest: “Hear the words that I speak in your ears. Not I alone, but all the prophets who have been before me, have prophesied long ago war, captivity, and pestilence, while you prophesy peace.” On this, Hananiah snatched the ox-yoke from the neck of Jeremiah, and broke it, saying, “Thus saith Jehovah, Even so will I break the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar from the neck of all nations within two years.” Jeremiah in reply said to this false prophet that he had broken a wooden yoke only to prepare an iron one for the people; for thus saith Jehovah: “I have put a yoke of iron on the neck of all these nations, that they shall serve the king of Babylon…. And further, hear this, O Hananiah! Jehovah has not sent thee, but thou makest this people trust in a lie; therefore thou shalt die this very year, because thou hast spoken rebellion against Jehovah.” In two months the lying prophet was dead.

Zedekiah, now awe-struck by the death of his counsellor, made up his mind to resist the Egyptian party and remain true to Nebuchadnezzar, and resolved to send an embassy to Babylon to vindicate himself from any suspicion of disloyalty; and further, he sought to win the favor of Jeremiah by a special gift to the Temple of a set of silver vessels to replace the golden ones that had been carried to Babylon. Jeremiah entered into his views, and sent with the embassy a letter to the exiles to warn them of the hopelessness of their cause. It was not well received, and created great excitement and indignation, since it seemed to exhort them to settle down contentedly in their slavery. The words of Jeremiah were, however, indorsed by the prophet Ezekiel, and he addressed the exiles from the place where he lived in Chaldaea, confirming the destruction which Jeremiah prophesied to unwilling ears. “Behold the day! See, it comes! The fierceness of Chaldaea has shot up into a rod to punish the wickedness of the people of Judah. Nothing shall remain of them. The time is come! Forge the chains to lead off the people captive. Destruction comes; calamity will follow calamity!”

Meanwhile, in spite of all these warnings from both Jeremiah and Ezekiel, things were passing at Jerusalem from bad to worse, until Nebuchadnezzar resolved on taking final vengeance on a rebellious city and people that refused to look on things as they were. Never was there a more infatuated people. One would suppose that a city already decimated, and its principal people already in bondage in Babylon, would not dare to resist the mightiest monarch who ever reigned in the East before the time of Cyrus. But “whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad.” Every preparation was made to defend the city. The general of Nebuchadnezzar with a great force surrounded it, and erected towers against the walls. But so strong were the fortifications that the inhabitants were able to stand a siege of eighteen months. At the end of this time they were driven to desperation, and fought with the energy of despair. They could resist battering rams, but they could not resist famine and pestilence. After dreadful sufferings, the besieged found the soldiers of Chaldaea within their Temple, a breach in the walls having been made, and the stubborn city was taken by assault. The few who were spared were carried away captive to Babylon with what spoil could be found, and the Temple and the walls were levelled to the ground. The predictions of the prophets were fulfilled,–the holy city was a heap of desolation. Zedekiah, with his wives and children, had escaped through a passage made in the wall, at a corner of the city which the Chaldeans had not been able to invest, and made his way toward Jericho, but was overtaken and carried in chains to Riblah, where Nebuchadnezzar was encamped. As he had broken a solemn oath to remain faithful, a severe judgment was pronounced upon him. His courtiers and his sons were executed in his sight, his own eyes were put out, and then he was taken to Babylon, where he was made to work like a slave in a mill. Thus ended the dynasty of David, in the year 588 B.C., about the time that Draco gave laws to Athens, and Tarquinius Priscus was king of Rome.

As for Jeremiah, during the siege of the city he fell into the power of the nobles, who beat him and imprisoned him in a dungeon. The king was not able to release him, so low had the royal power sunk in that disastrous age; but he secretly befriended him, and asked his counsel. The princes insisted on his removal to a place where no succor could reach him, and he was cast into a deep well from which the water was dried up, having at the bottom only slime and mud. From this pit of misery he was rescued by one of the royal guards, and once again he had a secret interview with Zedekiah, and remained secluded in the palace until the city fell. He was spared by the conqueror in view of his fidelity and his earnest efforts to prevent the rebellion, and perhaps also for his lofty character, the last of the great statesmen of Judah and the most distinguished man of the city. Nebuchadnezzar gave him the choice, to accompany him to Babylon with the promise of high favor at his court, or remain at home among the few that were not deemed of sufficient importance to carry away. Jeremiah preferred to remain amid the ruins of his country; for although Jerusalem was destroyed, the mountains and valleys remained, and the humble classes–the peasants–were left to cultivate the neglected vineyards and cornfields.

From Mizpeh, the city which he had selected as his last resting-place, Jeremiah was carried into Egypt, and his subsequent history is unknown. According to tradition he was stoned to death by his fellow-exiles in Egypt. He died as he had lived, a martyr for the truth, but left behind a great name and fame. None of the prophets was more venerated in after-ages. And no one more than he resembled, in his sufferings and life, that greater Prophet and Sage who was led as a lamb to the slaughter, that the world through him might be saved.

Judas Maccabaeus : Restoration of The Jewish Commonwealth

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets