Pride and Prejudice Introduction by Austin Dobson

Pride and Prejudice Introduction by Austin Dobson

One of the curiosities of modern criticism is a marked impatience of new prefaces to old books. Considered from one side only, the objection is intelligible. To the critic who can do without it, an introduction has no value; and if, in addition, it is inept and uninspired, he is fully justified in complaining that its lifeless bulk should be obtruded between the work and his nobility. But on the other hand, assuming it to be capable and instructed, it is surely a mistake to conclude, because one exceptionally gifted reader finds it superfluous, that it is not required by other people. The theory of its uselessness can only be supported by supposing that every one comes to a fresh reprint of a classic as well equipped as some particular critic :—

in other words, that all the world is so familiar with every existing introduction to the masterpiece concerned as to make any additional ‘preliminary matter’ a mere impertinence.

This is a palpable error; and it may be doubted whether even critical omniscience would claim so much.

The truth is, that such a book— unless bought solely for some accidental difference, as format, illustrations, type, or paper nearly always comes into the hands of a large percentage of its public for the first time, and any preface which it contains is as new to its new readers as if the volume had never before had its literary gentleman usher in the shape of an Epistle Deprecatory. That such will be the case with a new series of Miss Austen’s novels may fairly be anticipated, and, in these circumstances, no further apology need

be offered for the following record of her life and work.

Happily that record, to secure its brevity, involves no violent compression. For Jane Austen’s two-and-forty years were in reality little more than an uneventful sequence of what one of her predecessors in her art had gently satirised as ‘migrations from the blue bed to the brown.’

The larger portion of her life was spent in an out-of-the-way Hampshire parsonage, and the whole was so little chequered by incident of any kind that it was not until 1870, or more than fifty years after her death, that her descendants found courage to compile a Memoir. This Memoir, by her nephew, the Rev. J. E. Austen-Leigh, can scarcely be characterised as copious; and little was added to its facts by the carefully-edited collection of letters with which another relative, Lord Brabourne, followed it up fourteen years afterwards. From these sources we learn that she was the youngest child, and younger daughter, of the Rev. George Austen, Rector of Deane and Steventon, — a pluralist, as will be seen, but a pluralist with extenuating circumstances, since his parishes were little more than a mile apart, and their combined inhabitants less than three hundred souls. At Deane, where he at first resided, five sons were born to George Austen. Then, in 1771, he moved to Steventon, and here were born his two daughters, Cassandra and Jane, the latter on the 16th December 1775. Of her parents not much is related on which it is possible to base any definite theory as to hereditary traits. Her father was a handsome man, and a good scholar, who had been fellow of his college. Her mother, whose maiden name was Cassandra Leigh, is credited with an equable temper and a chastened gift of epigram. Mrs. Austen was, moreover, the niece of a once famous University wit and sometime Master of Balliol, Dr. Theophilus Leigh. [1] Out of this last fact the biographers of her daughter Jane have made all available capital.

The little village of Steventon, where Miss Austen was born, where she grew into womanhood, and where she wrote her first three novels, lies in the North Downs of Hampshire, at about equal distance from Whitchurch and Basingstoke. Its parsonage, now no longer standing, is not a very picturesque object in the representation of it which is given in the first edition of Mr. Austen-Leigh’s Memoir. But from his written description, it must have been pleasanter than it looks. Although situate in a ‘somewhat tame country,’ poor of soil, and barren of large timber, ‘the house itself stood in a shallow valley, surrounded by sloping meadows, well sprinkled with elm trees, at the end of a small village of cottages, … scattered about prettily on either side of the road.’ Behind it was a roomy, old-fashioned garden of flowers and vegetables combined, which also rejoiced in ‘a terrace of the finest turf.’ Hard by was the church, a very ancient but

spireless fane,

Just seen above the woody lane,

which was approached from the parsonage by one of those double Hampshire hedgerows with a path between them mentioned in Persuasion, and known in this particular instance as ‘the Church Walk.’ The Church Walk also led to the manor-house of Steventon, a gray old building screened by sycamores, the grounds of which were practically free to the rector’s family. Beyond the church and the manor house, there appears to have been nothing in Steventon to distinguish it from any other Hampshire village, but such as it was, Jane Austen found, in its peaceful rural scenes, a fitting nursing-ground for that delicate genius which, in the noise and bustle of town life, might easily have been dazed into hopeless silence.

The scanty details— and they are but scanty— which have been preserved of Miss Austen’s earlier years are wholly in keeping with the quiet household in which those years were spent. Her brothers, until they passed into the world (two of them rose to be Admirals), were educated by their father at home; and at home— in the intervals of visiting the neighbouring gentry in a primitive family coach, or of tramping the wet lanes in pattens— Cassandra and Jane also seem to have acquired what was then the sufficient equipment of a country parson’s daughter. In Jane’s case this consisted of a great deal of needlework, in which she was an adept, something of the piano, or ‘haspicholls’ (as Tony Lumpkin calls it), a great deal of French, a smattering of Italian, and an unusual amount of irreproachable English. Sometimes, at the instigation of a lively cousin, the widow of a French nobleman, there would be private theatricals in the barn, of which Mansfield Park retains the traces. But it will be readily understood that reading played no small part in Jane’s daily round. Of old periodicals and novels she is said to have been especially fond, and probably in the course of her visits to her cousins, the Coopers, at Bath, she had perused not a few of those stock specimens of the circulating library which the elder Colman schedules to the preface of Polly Honeycombe. Of Richardson and Miss Burney, the former especially, she was an enthusiastic admirer, and notwithstanding that the fact is ignored by her biographers, we suspect— upon the evidence of the admirable second chapter in Sense and Sensibility, where Mr. John Dashwood gradually persuades himself to give nothing whatever to his mother-in-law and sisters— that she was not unacquainted with the works of Fielding. Johnson’s prose she admired, and although she never, like Madame D’Arblay, fell into conscious mimicry of his style, was plainly not without recollections of that style in her earlier works.

Scott, Cowper, and Crabbe were her favourite poets, and it is significant that she liked the last the best. One of her critics thinks this ‘odd,’ but if anybody was likely to appeal to her instinctive bias towards minute veracity in art, it would surely be that homespun realist whom Thurlow likened to ‘Parson Adams,’ and the authors of the Rejected Addresses to ‘Pope in worsted stockings.’ Indeed it seems to have been a family joke, sanctioned by herself, that if she ever married, ‘she could fancy being Mrs.Crabbe’— an utterance which Mr. Austen-Leigh, careful of his kins woman’s good name, hastens to qualify by the discreet explanation that this was ‘looking on the author quite as an abstract idea, and ignorant and regardless what manner of man he might be.’

The anecdote, however, naturally suggests inquiry whether any incidents, not involving the consideration of male humanity as merely abstract ideas, had ever diversified the even tenor of Miss Austen’s life. In this respect it must be admitted that the evidence is of the most unsatisfying description. She was attractive, clever, and fond of pleasure, with all the healthy zest derived from a bright disposition and a sound physique, but the record of her affaires du cSuris of the vaguest. There are indeed indications of what must have been a smart flirtation with a certain good-looking and lively young Irishman named Tom Lefroy, who, as he was afterwards thrice married, should have been a marrying man; and we have the authority of Cassandra Austen for the statement that, at a Devonshire watering-place, very marked attentions were paid to her sister by a most eligible and gifted admirer who had the misfortune to die suddenly, and, like Gray, ‘never spoke out’ Of yet another pretendant we hear, who, possessing every ‘accomplishment’— in the phrase of the eighteenth century— ‘necessary to render the marriage state truly happy,’ was unsuccessful in engaging the affections of the lady. With all deference, therefore, to those who, like Byron’s Julia, look upon love as ‘woman’s whole existence,’ it must be concluded that Miss Austen’s suitors left her, as they found her, fancy free. It is certainly not necessary to suppose, as some do, that because she has drawn the operations of the ‘tender passion’ with exquisite skill, she must of necessity have experienced that ailment herself. Those who have sought to detect autobiography in scattered passages of Mansfield Park and Persuasion, seem to have over looked the fact that, while they attribute to the author the most unerring insight into the ordinary affairs of human life, they are practically denying her the exercise of that faculty in what is supposed to be, above all, the feminine province. Moreover, they must have forgotten that she was in constant and most confidential relations with an elder sister, who is admitted not only to have had a bonafide engagement, but also an engagement which was terminated disastrously by the premature death of her lover. On the whole, we may assume that Miss Austen had no definite romance of her own. As years went on, she accepted with equanimity the role of maiden aunt to her brothers’ children; and if it is accurate to say of any period of her life— in the words of theFrench song— L’Amour apasse parla, the marks of his footprints have now been irretrievably effaced.

But the evidence in respect of her love of letters presents no such difficulties. ‘It is impossible, Mr. Austen-Leigh tells us,’ to say at how early an age she began to write. There are copy-books extant containing tales some of which must have been composed while she was a young girl.

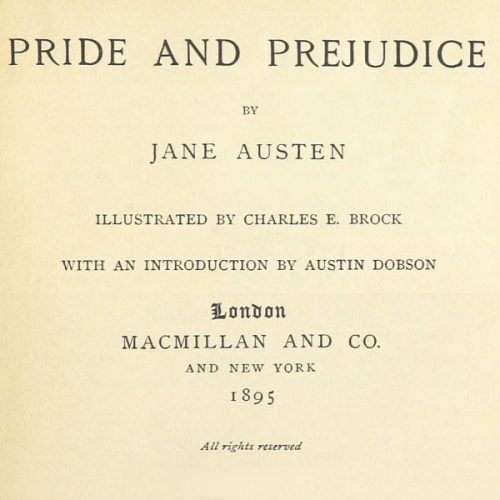

… Her earliest stories are of as light and flimsy texture, and are generally intended to be nonsensical, but the nonsense has much spirit in it’ They a real so, it is added, characterised by their ‘pure simple English,’ and yet, from their writer’s advice to a niece, it must be inferred that most of them were written long before she had reached sixteen. After these preliminary essays came a period in which her compositions took the form of tales, ‘generally burlesques, ridiculing the improbable events and exaggerated sentiments which she had met with in sundry silly romances,’— a description which reads like a characterisation of The Female Quixote of Mrs. Charlotte Lenox. Of this phase of her development some lingering traces are to be detected in Northanger Abbey, with its recollections of Mrs. Radcliffe. Then, towards 1792, she began, in the epistolary form of her favourite Richardson, a novel called Elinor and Marianne, which was followed by a shorter story, since included in her works under the title of Lady Susan. The former of these, recast and entirely revised, became Sense and Sensibility. But before she had thus transformed her earliest story she had completed the novel which, by universal consent, is regarded as her masterpiece— Pride andPrejudice. At this she began to work in October 1796, and finished it in August of the following year. The title originally chosen for it was First Impressions. Almost immediately afterwards, Sense and Sensibility began to assume its present form; and following this came, in 1798, Northanger Abbey.

As the second and third of these books will be more minutely examined in the special prefaces allotted to them, it is unnecessary to do more at present than note the curious fact that neither theynorPride and Prejudice were actually published until many years after this time. When the manuscript of Pride and Prejudice was finished, Mr. Austen pere, struck by the merit of the story, offered it by letter to Cadell, without, however, actually submitting the MS. for his inspection. Cadell declined even to look at it. No second effort was made by Mr. Austen to obtain for the book the honours of type, and it remained unprinted until 1813. An even more humiliating fate befell Northanger Abbey. In 1803 the MS. was offered to a Bath publisher (Peach, Historic Houses of Bath, thinks it must have been Bull of the Circulating Library), who bought it for £10. Having done so, he seems— like the first proprietors of the Vicar of Wakefield— to have repented of his rashness, for he locked his purchase in a drawer, and either dismissed the subject from his mind or forgot all about it until, many years afterwards, the MS. was diplomatically bought back by one of Miss Austen’s brothers.

To speak of Northanger Abbey, however, is to anticipate what belongs more properly to the introduction to that work. But it may be noted here that all the three novels above mentioned were written at Steventon. In May 1801, or about three years after the last of them was completed, Miss Austen’s father rather suddenly resigned his Hampshire living to his eldest son James, and moved to Bath, where the family lived at 4 Sydney Place, at Green Park Buildings, and (after Mr. Austen’s death, which took place in February 1805) in lodgings at 25 Gay Street. Bath, it might have been supposed, should have afforded a more congenial field of observation to Miss Austen’s analytic gift than the seclusion of Steventon, and those faded glories of the Basingstoke Balls to which she refers in one of her letters. But from one reason or another, perhaps because, for the moment, she lacked that stimulus of success without which the pursuit of literature resembles the drawing of nectar in a sieve, or because the care of a septuagenarian father and an invalid mother absorbed her more exclusively than before, Miss Austen’s stay of four and a half years in Beau Nash’s old city was not signalised by any fresh essays in fiction, save and except the fragment reprinted in 1871 by Mr. Austen-Leigh, with the afore-mentioned Lady Susan, under the title of The Watsons. It would be idle to dwell either upon the earlier work or the later fragment, which fragment, indeed, is little more than the first rough draft of an abandoned story, — abandoned, no doubt, under the temporary depression caused by the postponed publication of Northanger Abbey. But whether she enjoyed Bath, as one of her biographers concludes, or was bored by it, as another conjectures, — and, in the absence of trustworthy evidence, one supposition is as good as another, — it may safely be affirmed that, to the creative last years at Steventon, there had succeeded one of those fallow periods which fate does not often vouchsafe to the producers of masterpieces, and during which she was, intentionally or unintentionally, accumulating fresh reserves of recollection and experience.

While she was atBath she visited Lyme, — a visit which subsequently bore its fruit in an episode of Persuasion. This was in 1804. At the close of 1805 she removed with her mother and sister to Southampton, where they occupied ‘a commodious old-fashioned house in a corner of Castle Square’— then almost absorbed by the fantastic castellated mansion of the second Marquis of Lansdowne. The Southampton house was an agreeable one, but the locality proved even less stimulating than Bath to Miss Austen’s pen, for there is no record that anything was written while she made it her home. Then, in 1809, her second brother, Edward— who had been adopted by a rich relative, and had taken the name of Knight— offered his mother and sisters the choice of two houses on his property; one being near Godmersham Park in Kent, the other near Chawton House in Hampshire. They chose the latter, and settled themselves, with a lady friend, at Chawton Cottage, a little house standing in Chawton village, ‘about a mile from Alton, on the right-hand side, just where the road to Winchester branches off from that to Gosport’ Here Miss Austen was enpays de connaissance; in her old county, and among her own people. Circumstances brought many of her relatives into her neighbourhood; and here, practically, the remainder of her life was spent. Here, too, her dormant literary gift revived. At Chawton she wrote three more novels; and at Chawton she at last found a publisher for two of those which she had already completed.

Of these completed novels Sense and Sensibility was the first to appear in book form. Its adventurous putter-forth was Mr. T. Egerton of the ‘Military Library,’ Whitehall, who paid the author a sum which to her modest ambitions seemed ‘a prodigious recompense for that which had cost her nothing.’ She spent the first year of her residence at her new home in revising the work for the press, and it came out in 1811. No personal record of its reception, or of the author’s feelings upon that reception, seems to have survived. But the result must have encouraged both her publisher and herself, for in less than two years Egerton published First Impressions as Pride and Prejudice, an alliterative title modelled, we may suppose, on that of its predecessor. To Pride and Prejudice there are allusions in her correspondence. ‘Upon the whole,’ she tells her sister, ‘she is quite vain enough and well satisfied enough,’ though she considers ‘the work is rather too light, and bright, and sparkling; it wants shade; it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story; an essay on writing, a critique on Walter Scott, or the history ofBuonaparte,’ — in all of which, by the absence of these things, she shows how unerringly she had gauged her metier. Meanwhile she had entered upon some new work. ‘Between February 1811 and August 1816, she began and completed Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion.’ Of these only Mansfield Park and Emma appeared during her lifetime, — Egerton of the ‘Military Library’ being still the publisher of the former, John Murray of the latter.

Emma was dedicated, by permission, to thePrinceRegent, afterwards George IV. It is distinctly in the favour of that illustrious personage that he liked Miss Austen’s novels, of which, whether he really read them or not, he is affirmed to have kept a set in each of his houses. In connection with this dedication came, perhaps at the instance of His Royal Highness himself but from his librarian, Mr. J. S. Clarke, the suggestion that she should write a novel depicting ‘the habits of life, and character, and enthusiasm of a clergyman, who should pass his time between the metropolis and the country.’ Neither Goldsmith nor La Fontaine, Mr. Clarke was good enough to assure her, had achieved such a delineation. Miss Austen’s answer is worth quoting, because it shows how clearly defined were her notions of her powers; although she is perhaps over-modest as to her abilities when she describes herself as ‘the most unlearned and uninformed female who ever dared to be an authoress.’ She is not equal (she says) to the conception he suggests. ‘The comic part of the character’ she might do, ‘but not the good, the enthusiastic, the literary. Such a man’s conversation must at times be on subjects of science and philosophy, of which I know nothing; or at least be occasionally abundant in quotations and allusions which a woman who, like me, knows only her own mother tongue, and has read little in that, would be totally without the power of giving.’

Thereupon the irrepressible Mr. Clarke— mindful of the approaching marriage of the Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold, to the latter of whom he had been recently appointed Chaplain and private English Secretary— made the supplementary proposal that she should try her hand at ‘an historical romance illustrative of the august House of Cobourg.’ Miss Austen’s second reply may be inferred from her former one. ‘I could not,’ she answered, ‘sit seriously down to write a serious romance under any other motive than to save my life; and if it were indispensable for me to keep it up and never relax into laughing at myself or at other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first chapter. No, I must keep to my own style, and go on in my own way; and though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.’ The counsels of Prince Leopold’s chaplain are typical of the impracticable suggestions often received by authors from well-meaning persons, and Jane Austen’s unhesitating neglect of them is only another justification of Swift’s aphorism: ‘It is an uncontrolled truth that no man ever made an ill figure who understood his own talents, nor a good one whom is took them.’ There was not much writing of merit on the spindle-side in the Dean’s day, but his utterance is as applicable to women as to men.

In 1815, when Miss Austen’s acquaintance with Mr. Clarke began, she was nursing a sick brother at 23 Hans Place, Sloane Street (the ‘H. P.’ of Miss Mitford and the hapless L. E. L.). In April 1816, when her last-quoted words were written, she had returned once more to Chawton. The advice given her led to nothing more than a playful squib, which Mr. Austen-Leigh prints from her papers, entitled ‘Plan of a novel according to hints from various quarters.’ At this date her health had begun to fail. She still, however, persevered gallantly with her last novel Persuasion, which was eventually completed in August. In the year following she removed to Winchester for medical advice, taking lodgings with her sister in College Street. Here, although tenderly nursed, she sank gradually and peacefully. Being asked towards the end whether she wanted anything, she replied, ‘Nothing but death.’ This came on the morning of the 18th July 1817. On the 24th, she was buried in Winchester Cathedral, opposite the tomb of William of Wykeham, a large slab of black marble marking the place. Her mother survived her ten years, dying in 1827; her faithful confidante, nurse, and sister Cassandra lived to 1845.

There is apparently but one likeness of Miss Austen, that after a drawing by this sister Cassandra, which is prefixed to the first edition of Mr. Austen-Leigh’s Memoir. We are told that she was ‘a clear brunette with a rich colour,’ a detail scarcely to be gathered from the engraving. But she has large brilliant eyes, which the record says were hazel, a small well-formed nose, and a fine-cut but-thin-lipped mouth, suggesting something of precision and critical finesse. Her brown hair escapes in natural curls from a bandeau on her forehead, and is surmounted by the cap then indicative of middle age, but, it is suggested, assumed with needless precipitation by both Jane and her sister. For the rest, she wears the high waist and the short sleeves of the period, a costume from which, in a half-length, little can be inferred as to her figure generally. She is, however, affirmed to have been tall and elegant, extremely graceful in gait and motion, and in her ‘whole appearance expressing health and animation.’ Of her accomplishments little need be added to what has already been said. It should perhaps be noted that in addition to playing on the piano or harpsichord, she sang very sweetly, her preference being for songs of an old-fashioned kind. With children she was a great favourite, improvising for them the most enthralling fairy-stories, which she continued from day to day, and writing them occasionally the most delightfully gossiping epistles. Method, order, and neatness of hand were her prominent characteristics, — characteristics which, in the days that preceded adhesive envelopes, she extended to the closing and sealing of a letter. Her nephew’s praises of her proficiency in this respect, coupled with her neat script, recall the commendation which Praed gives to that ‘ballroom’s Belle’ who afterwards became ‘Mrs, Something Rogers’:—

She wrote a charming hand, — and oh!

How sweetly all her notes were folded!

As to her literary habits, the particulars preserved are not at first sight exactly what one would have expected. It might be supposed, for instance, that her careful lapidary style would have demanded, for its successful production, the utmost retirement and quiet, and it is true that her sojourn in large towns was curiously coincident with an unexplained suspension of literary activity. In other respects she does not seem to have required any particular conditions of environment. On the contrary, we are assured that while at Chawton she had no separate study, but wrote in the common sitting-room, where people came and went, only instinctively covering her manuscript from sight with a piece of blotting-paper when the visitor was unexpected, or the interruption prolonged. The little mahogany writing-desk at which her novels were composed was in 1871, and we presume still is, piously preserved by her descendants. With her, literature constituted, in truth, its ‘own exceeding great reward.’ Outside her own circle of intimates, few knew of her occupation or achievement; it was but tardily that her books found publishers; and when they were published, it was with equal tardiness that they made their way with a public accustomed to less refined and more demonstrative utterances. ‘To the multitude her works appeared tame and commonplace, poor in colouring, and sadly deficient in incident and interest’; and only faintly here and there a few isolated admirers had the audacity to compare her under their breaths with Miss Burney and Miss Edgeworth.

Not until 1821, or three years after her death, came the first real note of authoritative recognition, in the shape of a review contributed to the Quarterly by Dr. Whately, afterwards Archbishop of Dublin. Since this date a long list of readers of the highest distinction have said ditto to Dr. Whately. From these we may select two. Scott’s famous and frank admiration of her ‘talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life’ as a thing beyond his own powers, is well known. But his recently published ‘Journal’ contains a less familiar passage. Speaking of an evening spent over one of her novels, he writes, ‘There is a truth of painting in her writings which always delights me,’ and he goes on to say that in her own way she is ‘inimitable.’ This was written in 1827. Of Macaulay, his biographer tells us that he never for a moment wavered in his allegiance to Miss Austen. ‘If I could get materials, I really would write a short life of that wonderful woman, and raise a little money to put up a monument to her in Winchester Cathedral.’ So runs a sentence in his ‘Journal’ for 1858.

From the reader of to-day it is perhaps more difficult to obtain, at all events at first, a ratification of the praise which the great historian and the great romancer— both speaking, it may be observed, not with their considering caps on, but out of the fulness of their hearts in the privacy of their own personal records— gave to Miss Austen’s inventions.

To those familiar with the latest developments of the Novel, — developments embarrassed with accessories and description, perplexed with discussion of theology, heredity, insanity, and what not, — such a book as Emma or Persuasion must seem, as it is said to have seemed to some of its less jaded contemporary readers, almost ‘tame and common place.’ But I’appetitvient enmangeant, and this is not the verdict of a second perusal. The field may in a sense be ‘narrow’— no more, indeed, than ‘the little bit (two inches wide) of ivory’ to which the author refers in one of her letters— but the result within that narrow field is unique. Miss Austen realises her personages completely; she seems to know them minutely from their cradles to their graves; and she writes of themas if she were, not so much contriving scenes or incidents, as detaching from actual existences such a series of passages as would fall within the scope of her narrative. Her interest in her puppets, it is known, extended far beyond the limits of the story. ‘She would’— says her nephew— ‘if asked, tell us many little particulars about the subsequent career of some of her people,’ and he goes on to enumerate a few of these ‘amusing communications.’ It is true that, as Sir Walter allows, she moves chiefly among the middle classes, and, even there, keeps very much to the parlours; but had the greatest of artists competed with her on equal terms, it is difficult to see how she could have been excelled. Let it be granted that she could not have achieved a Falstaff, — a Dugald Dalgetty, — a Parson Adams. But would Shakespeare, or Scott, or Fielding have drawn a better Mr. Collins, or a more life like Mrs. Jennings? In her own walk she is ‘of imagination all compact’

Something of the origin of Pride and Prejudice has already been included in the foregoing general account of Miss Austen’s novels; and upon that head it is not possible to add much more. Nor is the book one which lends itself greatly to illustrative comment. If we except the account of Mr. Darcy’s place at Pemberley, there is little or no topography ; there is no detailed or elaborated description of persons or accessories; there are none of those interspaces of reflection and digression— those ‘long chapters of sense’ or ‘solemn specious nonsense’— of which she herself half seriously, half humorously, deplored the deficiency. Going over her pages, pencil in hand, the antiquarian annotator is struck by their excessive ‘modernity,’ and after a prolonged examination, discovers, in this century-old record, nothing more fitted for the exercise of his ingenuity than such an obsolete game at cards as ‘cassino’ or ‘quadrille.’ The philologist is in no better case. He speedily arrives at the conclusion that he will find in Madame D’Arblay and Miss Edgeworth— to cite writers who are more or less in Miss Austen’s line— a far more profitable hunting-ground for archaisms, and he probably falls back upon admiration of the finished and perspicuous style. To say nothing of the supreme excellence of the dialogue, there is scarcely a page but has its little gem of exact and polished phrasing; scarcely a chapter which is not adroitly opened or artistically ended; while the whole book abounds in sentences over which the writer, it is plain, must have lingered with patient and loving craftsmanship. To take but one at random, — Could anything be better put than this Goldsmith-like characterisation of the small talk of Mrs. Hurst and Miss Bingley?—

‘Their powers of conversation were considerable. They could describe an entertainment with accuracy, relate an anecdote with humour, and laugh at their acquaintance with spirit,’ Or this casual utterance of Mr. Bingley:

‘I declare I do not know a more awful object than Darcy on particular occasions, and in particular places; at his own house especially, and of a Sunday evening, when he has nothing to do.’ Excellent again is the solemn persiflage of Mr. Bennet. ‘It is happy for you,’ he tells the fulsome Mr. Collins, ‘that you possess the talent of flattering with delicacy. May Iask whether these pleasing attentions proceed from the impulse of the moment, or are the result of previous study ?’

Miss Austen’s enthusiasm, it is reported, was only faintly stirred by the delicate raillery of the Spectator. But the last quotation shows that she had somehow contrived to acquire that ‘artifice of mischief which Esther Johnson approved in Addison, and which consists in humouring a fool to the top of his folly.

Criticism has found little to condemn in the details of this capital novel. Nobody, nowadays— assuredly nobody who has the requisite respect for its delightful heroine— is likely to re-echo the unchivalrous insinuation of one of its early reviewers that Elizabeth’s change of sentiment towards Darcy is caused by the sight of his house and grounds. A graver objection, and an objection perhaps less easy to dismiss, is that Darcy’s manner is at first almost too insufferable, and, moreover, that it is difficult to reconcile his bearing at his appearance on the scene with the accounts which are afterwards given of his amiable manners in boyhood and youth. But to this it maybe answered that he is not the only hero who develops unexpectedly during the progress of a story; witness, for example, the notorious cases of Mr. Pickwick and Don Quixote; and also that something decidedly abnormal was required at the outset, both to justify his ‘pride’ and the ‘prejudice’ with which Elizabeth begins by regarding him. Another thing which has been noted is that Mrs. Bennet is almost too absolutely foolish a mother for such charming daughters as the two eldest, and that Lydia’s elopement is out of keeping with the story. But it was not out of keeping with some of Miss Austen’s eighteenth-century models, nor, indeed, with the manners of her day; and, as regards the other contention, Elizabeth, at least, is more the daughter of her clever father than her silly mother, who, silly though she seems, is not unparalleled in most experiences. A more material, though still a very minor, criticism would be that the work could well have dispensed with two of the Bennet girls, and that Mary and Kitty have no very indispensable function in the plot. But of the rest of the personages none could be spared. Mr.Collins is impayable; so is Lady Catherine de Bourgh; so is Mr. Bennet; and upon their lower planes, so are Mrs. Bennet, Sir William Lucas and his daughter Charlotte. Mr. Bingley, in an unobtrusive way, is very agreeable, and Jane Bennet, in the same degree, is charming.

Of the finally-revealed and reformed Mr. Darcy one can only add that he appears worthy of his good fortune.

Dr. Johnson affirmed that Fielding’s Amelia was ‘the most pleasing heroine of all the romances.’ One wonders what the good Doctor would have said to this later creation of the disciple of his favourite ‘little Burney, ‘— what he would have said to Elizabeth Bennet! She is certainly a most captivating figure. It is not alone that she is personally attractive, or rather that she has exceptional personal charm, but she is intellectually engaging as well. Her high spirit, her wit, her perfect command of epigrammatic expression, her ready gift of repartee, and above all, her admirable faculty for taking care of herself, — these things would be enough to secure admirers, even without the good sense and good feeling which are the basis of her character. I fit were not that the author says expressly in one of her letters that she had vainly searched the exhibition in Spring Gardens in the hope of finding Elizabeth’s prototype (an announcement which reminds one of Cibber perambulating Ranelagh for Richardson’s Clarissa), we should have fancied that Miss Austen’s best course would have been to consult her own mirror. When we read of Elizabeth’s fresh colour and ‘fine eyes,’ we think instinctively of Cassandra Austen’s portrait of her sister. And there are unquestionably sentences describing Miss Eliza Bennet which fit her creator like a glove. When, for example, Elizabeth tells Mr. Bingley that she delights in the study of intricate character, and that even in a very confined and unvarying country society people alter so much that there is something new to be observed in them for ever, she is obviously speaking with the voice of Miss Austen. When she watches with amusement Miss Bingley’s maladroit attentions to Mr. Darcy while he is writing to his sister in Chap.X., we feel sure that she is only doing what Miss Austen must often have done; while a sentence of Elizabeth in the chapter that follows might almost serve as a defence of Miss Austen’s work:

‘I hope In ever ridicule what is wise or good. Follies and nonsense, whims and inconsistencies, do divert me, I own, and I laugh at them whenever I can.’

1 Some of Dr. Leigh’s jokes are quoted by his great-niece’s biographer. Even in old age — and he lived to be ninety— he retained this faculty. A day or two before his death some one said that an old acquaintance had been egged on to matrimony. ‘Then may the yoke sit easy on him,’ said Dr. Leigh.