Paula : Woman as Friend – Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

Cyrus the Great : Asiatic Supremacy

Julius Caesar : Imperialism

Marcus Aurelius : Glory of Rome

Constantine the Great : Christianity Enthroned

Paula : Woman as Friend

Chrysostom : Sacred Eloquence

Saint Ambrose : Episcopal Authority

Saint Augustine : Christian Theology

Theodosius the Great : Latter Days of Rome

Leo the Great : Foundation of the Papacy

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Female friendship

Paganism unfavorable to friendship

Character of Jewish women

Great Pagan women

Paula, her early life

Her conversion to Christianity

Her asceticism

Asceticism the result of circumstances

Virtues of Paula

Her illustrious friends

Saint Jerome and his great attainments

His friendship with Paula

His social influence at Rome

His treatment of women

Vanity of mere worldly friendship

Esthetic mission of woman

Elements of permanent friendship

Necessity of social equality

Illustrious friendships

Congenial tastes in friendship

Necessity of Christian graces

Sympathy as radiating from the Cross

Necessity of some common end in friendship

The extension of monastic life

Virtues of early monastic life

Paula and Jerome seek its retreats

Their residence in Palestine

Their travels in the East

Their illustrious visitors

Peculiarities of their friendship

Death of Paula

Her character and fame

Elevation of woman by friendship

Paula : Woman as Friend

A.D. 347-404.

The subject of this lecture is Paula, an illustrious Roman lady of rank and wealth, whose remarkable friendship for Saint Jerome, in the latter part of the fourth century, has made her historical. If to her we do not date the first great change in the social relations of man with woman, yet she is the most memorable example that I can find of that exalted sentiment which Christianity called out in the intercourse of the sexes, and which has done more for the elevation of society than any other sentiment except that of religion itself.

Female friendship, however, must ever have adorned and cheered the world; it naturally springs from the depths of a woman’s soul. However dark and dismal society may have been under the withering influences of Paganism, it is probable that glorious instances could be chronicled of the devotion of woman to man and of man to woman, which was not intensified by the passion of love. Nevertheless, the condition of women in the Pagan world, even with all the influences of civilization, was unfavorable to that sentiment which is such a charm in social life.

The Pagan woman belonged to her husband or her father rather than to herself. As more fully shown in the discussion of Cleopatra, she was universally regarded as inferior to man, and made to be his slave. She was miserably educated; she was secluded from intercourse with strangers; she was shut up in her home; she was given in marriage without her consent; she was guarded by female slaves; she was valued chiefly as a domestic servant, or as an animal to prevent the extinction of families; she was seldom honored; she was doomed to household drudgeries as if she were capable of nothing higher; in short, her lot was hard, because it was unequal, humiliating, and sometimes degrading, making her to be either timorous, frivolous, or artful. Her amusements were trivial, her taste vitiated, her education neglected, her rights violated, her aspirations scorned. The poets represented her as capricious, fickle, and false. She rose only to fall; she lived only to die. She was a victim, a toy, or a slave. Bedizened or burdened, she was either an object of degrading admiration or of cold neglect.

The Jewish women seem to have been more favored and honored than women were in Greece or Rome, even in the highest periods of their civilization. But in Jewish history woman was the coy maiden, or the vigilant housekeeper, or the ambitious mother, or the intriguing wife, or the obedient daughter, or the patriotic song-stress, rather than the sympathetic friend. Though we admire the beautiful Rachel, or the heroic Deborah, or the virtuous Abigail, or the affectionate Ruth, or the fortunate Esther, or the brave Judith, or the generous Shunamite, we do not find in the Rachels and Esthers the hallowed ministrations of the Marys, the Marthas and the Phoebes, until Christianity had developed the virtues of the heart and kindled the loftier sentiments of the soul. Then woman became not merely the gentle nurse and the prudent housewife and the disinterested lover, but a friend, an angel of consolation, the equal of man in character, and his superior in the virtues of the heart and soul. It was not till then that she was seen to have those qualities which extort veneration, and call out the deepest sympathy, whenever life is divested of its demoralizing egotisms. The original beatitudes of the Garden of Eden returned, and man awoke from the deep sleep of four thousand years, to discover, with Adam, that woman was a partner for whom he should resign all the other attachments of life; and she became his star of worship and his guardian angel amid the entanglements of sin and cares of toil.

I would not assert that there were not noble exceptions to the frivolities and slaveries to which women were generally doomed in Pagan Greece and Rome. Paganism records the fascinations of famous women who could allure the greatest statesmen and the wisest moralists to their charmed circle of admirers,–of women who united high intellectual culture with physical beauty. It tells us of Artemisia, who erected to her husband a mausoleum which was one of the wonders of the world; of Telesilla, the poetess, who saved Argos by her courage; of Hipparchia, who married a deformed and ugly cynic, in order that she might make attainments in learning and philosophy; of Phantasia, who wrote a poem on the Trojan war, which Homer himself did not disdain to utilize; of Sappho, who invented a new measure in lyric poetry, and who was so highly esteemed that her countrymen stamped their money with her image; of Volumnia, screening Rome from the vengeance of her angry son; of Servilia, parting with her jewels to secure her father’s liberty; of Sulpicia, who fled from the luxuries of Rome to be a partner of the exile of her husband; of Hortensia, pleading for justice before the triumvirs in the market-place; of Octavia, protecting the children of her rival Cleopatra; of Lucretia, destroying herself rather than survive the dishonor of her house; of Cornelia, inciting her sons, the Gracchi, to deeds of patriotism; and many other illustrious women. We read of courage, fortitude, patriotism, conjugal and parental love; but how seldom do we read of those who were capable of an exalted friendship for men, without provoking scandal or exciting rude suspicion? Who among the poets paint friendship without love; who among them extol women, unless they couple with their praises of mental and moral qualities a mention of the delights of sensual charms and of the joys of wine and banquets? Poets represent the sentiments of an age or people; and the poets of Greece and Rome have almost libelled humanity itself by their bitter sarcasms, showing how degraded the condition of woman was under Pagan influences.

Now, I select Paula, to show that friendship–the noblest sentiment in woman–was not common until Christianity had greatly modified the opinions and habits of society; and to illustrate how indissolubly connected this noble sentiment is with the highest triumphs of an emancipating religion. Paula was a highly favored as well as a highly gifted woman. She was a descendant of the Scipios and the Gracchi, and was born A.D. 347, at Rome, ten years after the death of the Great Constantine who enthroned Christianity, but while yet the social forces of the empire were entangled in the meshes of Paganism. She was married at seventeen to Toxotius, of the still more illustrious Julian family. She lived on Mount Aventine, in great magnificence. She owned, it is said, a whole city in Italy. She was one of the richest women of antiquity, and belonged to the very highest rank of society in an aristocratic age. Until her husband died, she was not distinguished from other Roman ladies of rank, except for the splendor of her palace and the elegance of her life. It seems that she was first won to Christianity by the virtues of the celebrated Marcella, and she hastened to enroll herself, with her five daughters, as pupils of this learned woman, at the same time giving up those habits of luxury which thus far had characterized her, together with most ladies of her class. On her conversion, she distributed to the poor the quarter part of her immense income,–charity being one of the forms which religion took in the early ages of Christianity. Nor was she contented to part with the splendor of her ordinary life. She became a nurse of the miserable and the sick; and when they died she buried them at her own expense. She sought out and relieved distress wherever it was to be found.

But her piety could not escape the asceticism of the age; she lived on bread and a little oil, wasted her body with fastings, dressed like a servant, slept on a mat of straw, covered herself with haircloth, and denied herself the pleasures to which she had been accustomed; she would not even take a bath. The Catholic historians have unduly magnified these virtues; but it was the type which piety then assumed, arising in part from a too literal interpretation of the injunctions of Christ. We are more enlightened in these times, since modern Christian civilization seeks to solve the problem how far the pleasures of this world may be reconciled with the pleasures of the world to come. But the Christians of the fourth century were more austere, like the original Puritans, and made but little account of pleasures which weaned them from the contemplation of God and divine truth, and chained them to the triumphal car of a material and infidel philosophy. As the great and besetting sin of the Jews before the Captivity was idolatry, which thus was the principal subject of rebuke from the messengers of Omnipotence,–the one thing which the Jews were warned to avoid; as hypocrisy and Pharisaism and a technical and legal piety were the greatest vices to be avoided when Christ began his teachings,–so Epicureanism in life and philosophy was the greatest evil with which the early Christians had to contend, and which the more eminent among them sought to shun, like Athanasius, Basil, and Chrysostom. The asceticism of the early Church was simply the protest against that materialism which was undermining society and preparing the way to ruin; and hence the loftiest type of piety assumed the form of deadly antagonism to the luxuries and self-indulgence which pervaded every city of the empire.

This antagonism may have been carried too far, even as the Puritan made war on many innocent pleasures; but the spectacle of a self-indulgent and pleasure-seeking Christian was abhorrent to the piety of those saints who controlled the opinions of the Christian world. The world was full of misery and poverty, and it was these evils they sought to relieve. The leaders of Pagan society were abandoned to gains and pleasures, which the Christians would fain rebuke by a lofty self-denial,–even as Stoicism, the noblest remonstrance of the Pagan intellect, had its greatest example in an illustrious Roman emperor, who vainly sought to stem the vices which he saw were preparing the way for the conquests of the barbarians. The historian who does not take cognizance of the great necessities of nations, and of the remedies with which good men seek to meet these necessities, is neither philosophical nor just; and instead of railing at the saints,–so justly venerated and powerful,–because they were austere and ascetic, he should remember that only an indifference to the pleasures and luxuries which were the fatal evils of their day could make a powerful impression even on the masses, and make Christianity stand out in bold contrast with the fashionable, perverse, and false doctrines which Paganism indorsed. And I venture to predict, that if the increasing and unblushing materialism of our times shall at last call for such scathing rebukes as the Jewish prophets launched against the sin of idolatry, or such as Christ himself employed when he exposed the hollowness of the piety of the men who took the lead in religious instruction in his day, then the loftiest characters–those whose example is most revered–will again disdain and shun a style of life which seriously conflicts with the triumphs of a spiritual Christianity.

Paula was an ascetic Roman matron on her conversion, or else her conversion would then have seemed nominal. But her nature was not austere. She was a woman of great humanity, and distinguished for those generous traits which have endeared Augustine to the heart of the world. Her hospitalities were boundless; her palace was the resort of all who were famous, when they visited the great capital of the empire. Nor did her asceticism extinguish the natural affections of her heart. When one of her daughters died, her grief was as immoderate as that of Bernard on the loss of his brother. The woman was never lost in the saint. Another interesting circumstance was her enjoyment of cultivated society, and even of those literary treasures which imperishable art had bequeathed. She spoke the Greek language as an English or Russian nobleman speaks French, as a theological student understands German. Her companions were gifted and learned women. Intimately associated with her in Christian labors was Marcella,–a lady who refused the hand of the reigning Consul, and yet, in spite of her duties as a leader of Christian benevolence, so learned that she could explain intricate passages of the Scriptures; versed equally in Greek and Hebrew; and so revered, that, when Rome was taken by the Goths, her splendid palace on Mount Aventine was left unmolested by the barbaric spoliators. Paula was also the friend and companion of Albina and Marcellina, sisters of the great Ambrose, whose father was governor of Gaul. Felicita, Principia, and Feliciana also belonged to her circle,–all of noble birth and great possessions. Her own daughter, Blessella, was married to a descendant of Camillus; and even the illustrious Fabiola, whose life is so charmingly portrayed by Cardinal Wiseman, was also a member of this chosen circle.

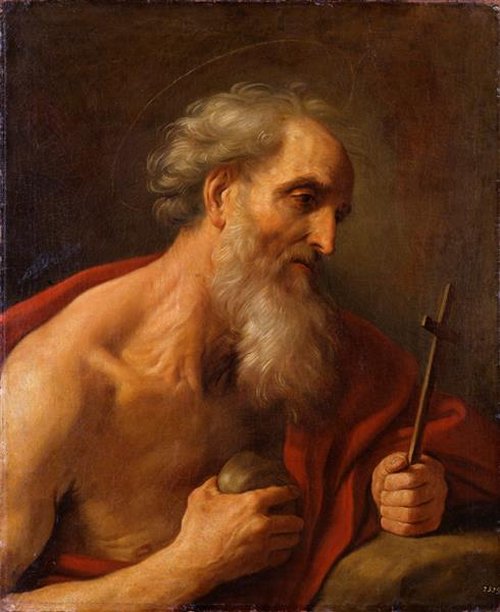

It was when Rome was the field of her charities and the scene of her virtues, when she equally blazed as a queen of society and a saint of the most self-sacrificing duties, that Paula fell under the influence of Saint Jerome, at that time secretary of Pope Damasus,–the most austere and the most learned man of Christian antiquity, the great oracle of the Latin Church, sharing with Augustine the reverence bestowed by succeeding ages, whose translation of the Scriptures into Latin has made him an immortal benefactor. Nor was Jerome a plebeian; he was a man of rank and fortune,–like the more famous of the Fathers,–but gave away his possessions to the poor, as did so many others of his day. Nothing had been spared on his education by his wealthy Illyrian parents. At eighteen he was sent to Rome to complete his studies. He became deeply imbued with classic literature, and was more interested in the great authors of Greece and Rome than in the material glories of the empire. He lived in their ideas so completely, that in after times his acquaintance with even the writings of Cicero was a matter of self-reproach. Disgusted, however, with the pomps and vanities around him, he sought peace in the consolations of Christianity. His ardent nature impelled him to embrace the ascetic doctrines which were so highly esteemed and venerated; he buried himself in the catacombs, and lived like a monk. Then his inquiring nature compelled him to travel for knowledge, and he visited whatever was interesting in Italy, Greece, and Asia Minor, and especially Palestine, finally fixing upon Chalcis, on the confines of Syria, as his abode. There he gave himself up to contemplation and study, and to the writing of letters to all parts of Christendom. These letters and his learned treatises, and especially the fame of his sanctity, excited so much interest that Pope Damasus summoned him back to Rome to become his counsellor and secretary. More austere than Bossuet or Fénelon at the court of Louis XIV., he was as accomplished, and even more learned than they. They were courtiers; he was a spiritual dictator, ruling, not like Dunstan, by an appeal to superstitious fears, but by learning and sanctity. In his coarse garments he maintained his equality with princes and nobles. To the great he appeared proud and repulsive. To the poor he was affable, gentle, and sympathetic; they thought him as humble as the rich thought him arrogant.

Such a man–so learned and pious, so courtly in his manners, so eloquent in his teachings, so independent and fearless in his spirit, so brilliant in conversation, although tinged with bitterness and sarcasm–became a favorite in those high circles where rank was adorned by piety and culture. The spiritual director became a friend, and his friendship was especially valued by Paula and her illustrious circle. Among those brilliant and religious women he was at home, for by birth and education he was their equal. At the house of Paula he was like Whitefield at the Countess of Huntingdon’s, or Michael Angelo in the palace of Vittoria Colonna,–a friend, a teacher, and an oracle.

St. Jerome From the painting by Guido Reni, Dresden Germany

So, in the midst of a chosen and favored circle did Jerome live, with the bishops and the doctors who equally sought the exalted privilege of its courtesies and its kindness. And the friendship, based on sympathy with Christian labors, became strengthened every day by mutual appreciation, and by that frank and genial intercourse which can exist only with cultivated and honest people. Those high-born ladies listened to his teachings with enthusiasm, entered into all his schemes, and gave him most generous co-operation; not because his literary successes had been blazed throughout the world, but because, like them, he concealed under his coarse garments and his austere habits an ardent, earnest, eloquent soul, with intense longings after truth, and with noble aspirations to extend that religion which was the only hope of the decaying empire. Like them, he had a boundless contempt for empty and passing pleasures, for all the plaudits of the devotees to fashion; and he appreciated their trials and temptations, and pointed out, with more than fraternal tenderness, those insidious enemies that came in the disguise of angels of light. Only a man of his intuitions could have understood the disinterested generosity of those noble women, and the passionless serenity with which they contemplated the demons they had by grace exorcised; and it was only they, with their more delicate organization and their innate insight, who could have entered upon his sorrows, and penetrated the secrets he did not seek to reveal. He gave to them his choicest hours, explained to them the mysteries, revealed his own experiences, animated their hopes, removed their stumbling-blocks, encouraged them in missions of charity, ignored their mistakes, gloried in their sacrifices, and held out to them the promised joys of the endless future. In return, they consoled him in disappointment, shared his resentments, exulted in his triumphs, soothed him in his toils, administered to his wants, guarded his infirmities, relieved him from irksome details, and inspired him to exalted labors by increasing his self-respect. Not with empty flatteries, nor idle dalliances, nor frivolous arts did they mutually encourage and assist each other. Sincerity and truthfulness were the first conditions of their holy intercourse,–“the communion of saints,” in which they believed, the sympathies of earth purified by the aspirations of heaven; and neither he nor they were ashamed to feel that such a friendship was more precious than rubies, being sanctioned by apostles and martyrs; nay, without which a Bethany would have been as dreary as the stalls and tables of money-changers in the precincts of the Temple.

A mere worldly life could not have produced such a friendship, for it would have been ostentatious, or prodigal, or vain; allied with sumptuous banquets, with intellectual tournaments, with selfish aims, with foolish presents, with emotions which degenerate into passions Ennui, disappointment, burdensome obligation, ultimate disgust, are the result of what is based on the finite and the worldly, allied with the gifts which come from a selfish heart, with the urbanities which are equally showered on the evil and on the good, with the graces which sometimes conceal the poison of asps. How unsatisfactory and mournful the friendship between Voltaire and Frederic the Great, with all their brilliant qualities and mutual flatteries! How unmeaning would have been a friendship between Chesterfield and Dr. Johnson, even had the latter stooped to all the arts of sycophancy! The world can only inspire its votaries with its own idolatries. Whatever is born of vanity will end in vanity. “Even in laughter the heart is sorrowful, and the end of that mirth is heaviness.” But when we seek in friends that which can perpetually refresh and never satiate,–the counsel which maketh wise, the voice of truth and not the voice of flattery; that which will instruct and never degrade, the influences which banish envy and mistrust,–then there is a precious life in it which survives all change. In the atmosphere of admiration, respect, and sympathy suspicion dies, and base desires pass away for lack of their accustomed nourishment; we see defects through the glass of our own charity, with eyes of love and pity, while all that is beautiful is rendered radiant; a halo surrounds the mortal form, like the glory which mediaeval artists aspired to paint in the faces of Madonnas; and adoration succeeds to sympathy, since the excellences we admire are akin to the perfections we adore. “The occult elements” and “latent affinities,” of which material pursuits never take cognizance, are “influences as potent in adding a charm to labor or repose as dew or air, in the natural world, in giving a tint to flowers or sap to vegetation.”

In that charmed circle, in which it would be difficult to say whether Jerome or Paula presided, the aesthetic mission of woman was seen fully,–perhaps for the first time,–which is never recognized when love of admiration, or intellectual hardihood, or frivolous employments, or usurped prerogatives blunt original sensibilities and sap the elements of inward life. Sentiment proved its superiority over all the claims of intellect,–as when Flora Macdonald effected the escape of Charles Stuart after the fatal battle of Culloden, or when Mary poured the spikenard on Jesus’ head, and wiped his feet with the hairs of her head. The glory of the mind yielded to the superior radiance of an admiring soul, and equals stood out in each other’s eyes as gifted superiors whom it was no sin to venerate. Radiant in the innocence of conscious virtue, capable of appreciating any flights of genius, holding their riches of no account except to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, these friends lived only to repair the evils which unbridled sin inflicted on mankind,–glorious examples of the support which our frail nature needs, the sun and joy of social life, perpetual benedictions, the sweet rest of a harassed soul.

Strange it is that such a friendship was found in the most corrupt, conventional, luxurious city of the empire. It is not in cities that friendships are supposed to thrive. People in great towns are too preoccupied, too busy, too distracted to shine in those amenities which require peace and rest and leisure. Bacon quotes the Latin adage, Magna civitas, magna solitudo. It is in cities where real solitude dwells, since friends are scattered, “and crowds are not company, and faces are only as a gallery of pictures, and talk but a tinkling cymbal, where there is no love.”

The history of Jerome and Paula suggests another reflection,–that the friendship which would have immortalized them, had they not other and higher claims to the remembrance and gratitude of mankind, rarely exists except with equals. There must be sympathy in the outward relations of life, as we are constituted, in order for men and women to understand each other. Friendship is not philanthropy: it is a refined and subtile sentiment which binds hearts together in similar labors and experiences. It must be confessed it is exclusive, esoteric,–a sort of moral freemasonry. Jerome, and the great bishops, and the illustrious ladies to whom I allude, all belonged to the same social ranks. They spent their leisure hours together, read the same books, and kindled at the same sentiments. In their charmed circle they unbent; indulged, perchance, in ironical sallies on the follies they alike despised. They freed their minds, as Cicero did to Atticus; they said things to each other which they might have hesitated to say in public, or among fools and dunces. I can conceive that those austere people were sometimes even merry and jocose. The ignorant would not have understood their learned allusions; the narrow-minded might have been shocked at the treatment of their shibboleths; the vulgar would have repelled them by coarseness; the sensual would have disgusted them by their lower tastes.

There can be no true harmony among friends when their sensibilities are shocked, or their views are discrepant. How could Jerome or Paula have discoursed with enthusiasm of the fascinations of Eastern travel to those who had no desire to see the sacred places; or of the charms of Grecian literature to those who could talk only in Latin; or of the corrupting music of the poets to people of perverted taste; or of the sublimity of the Hebrew prophets to those who despised the Jews; or of the luxury of charity to those who had no superfluities; or of the beatitudes of the passive virtues to soldiers; or of the mysteries of faith to speculating rationalists; or of the greatness of the infinite to those who lived in passing events? A Jewish prophet must have seemed a rhapsodist to Athenian critics, and a Grecian philosopher a conceited cynic to a converted fisherman of Galilee,–even as a boastful Darwinite would be repulsive to a believer in the active interference of the moral Governor of the universe. Even Luther might not have admired Michael Angelo, any more than the great artist did the courtiers of Julius II.; and John Knox might have denounced Lord Bacon as a Gallio for advocating moderate measures of reform. The courtly Bossuet would not probably have sympathized with Baxter, even when both discoursed on the eternal gulf between reason and faith. Jesus–the wandering, weary Man of Sorrows–loved Mary and Martha and Lazarus; but Jesus, in the hour of supreme grief, allowed the most spiritual and intellectual of his disciples to lean on his bosom. It was the son of a king whom David cherished with a love surpassing the love of woman. It was to Plato that Socrates communicated his moral wisdom; it was with cultivated youth that Augustine surrounded himself in the gardens of Como; Caesar walked with Antony, and Cassius with Brutus; it was to Madame de Maintenon that Fénelon poured out the riches of his intellect, and the lofty Saint Cyran opened to Mère Angelique the sorrows of his soul. We associate Aspasia with Pericles; Cicero with Atticus; Héloïse with Abélard; Hildebrand with the Countess Matilda; Michael Angelo with Vittoria Colonna; Cardinal de Retz with the Duchess de Longueville; Dr. Johnson with Hannah More.

Those who have no friends delight most in the plaudits of a plebeian crowd. A philosopher who associates with the vulgar is neither an oracle nor a guide. A rich man’s son who fraternizes with hostlers will not long grace a party of ladies and gentlemen. A politician who shakes hands with the rabble will lose as much in influence as he gains in power. In spite of envy, poets cling to poets and artists to artists. Genius, like a magnet, draws only congenial natures to itself. Had a well-bred and titled fool been admitted into the Turk’s-Head Club, he might have been the butt of good-natured irony; but he would have been endured, since gentlemen must live with gentlemen and scholars with scholars, and the rivalries which alienate are not so destructive as the grossness which repels. More genial were the festivities of a feudal castle than any banquet between Jews and Samaritans. Had not Mrs. Thrale been a woman of intellect and sensibility, the hospitalities she extended to Johnson would have been as irksome as the dinners given to Robert Hall by his plebeian parishioners; and had not Mrs. Unwin been as refined as she was sympathetic, she would never have soothed the morbid melancholy of Cowper, while the attentions of a fussy, fidgety, talkative, busy wife of a London shopkeeper would have driven him absolutely mad, even if her disposition had been as kind as that of Dorcas, and her piety as warm as that of Phoebe. Paula was to Jerome what Arbella Johnson was to John Winthrop, because their tastes, their habits, their associations, and their studies were the same,–they were equals in rank, in culture, and perhaps in intellect.

But I would not give the impression that congenial tastes and habits and associations formed the basis of the holy friendship between Paula and Jerome. The fountain and life of it was that love which radiated from the Cross,–an absorbing desire to extend the religion which saves the world. Without this foundation, their friendship might have been transient, subject to caprice and circumstances,–like the gay intercourse between the wits who assembled at the Hôtel de Rambouillet, or the sentimental affinities which bind together young men at college or young girls at school, when their vows of undying attachment are so often forgotten in the hard struggles or empty vanities of subsequent life. Circumstances and affinities produced those friendships, and circumstances or time dissolved them,–like the merry meetings of Prince Hal and Falstaff; like the companionship of curious or ennuied travellers on the heights of Righi or in the galleries of Florence. The cord which binds together the selfish and the worldly in the quest for pleasure, in the search for gain, in the toil for honors, at a bacchanalian feast, in a Presidential canvass, on a journey to Niagara,–is a rope of sand; a truth which the experienced know, yet which is so bitter to learn. It is profound philosophy, as well as religious experience, which confirms this solemn truth. The soul can repose only on the certitudes of heaven; those who are joined together by the gospel feel alike the misery of the fall and the glory of the restoration. The impressive earnestness which overpowers the mind when eternal and momentous truths are the subjects of discourse binds people together with a force of sympathy which cannot be produced by the sublimity of a mountain or the beauty of a picture. And this enables them to bear each other’s burdens, and hide each other’s faults, and soothe each other’s resentments; to praise without hypocrisy, rebuke without malice, rejoice without envy, and assist without ostentation. This divine sympathy alone can break up selfishness, vanity, and pride. It produces sincerity, truthfulness, disinterestedness,–without which any friendship will die. It is not the remembrance of pleasure which keeps alive a friendship, but the perception of virtues. How can that live which is based on corruption or a falsehood? Anything sensual in friendship passes away, and leaves a residuum of self-reproach, or undermines esteem. That which preserves undying beauty and sacred harmony and celestial glory is wholly based on the spiritual in man, on moral excellence, on the joys of an emancipated soul. It is not easy, in the giddy hours of temptation or folly, to keep this truth in mind, but it can be demonstrated by the experience of every struggling character. The soul that seeks the infinite and imperishable can be firmly knit only to those who live in the realm of adoration,–the adoration of beauty, or truth, or love; and unless a man or woman does prefer the infinite to the finite, the permanent to the transient, the true to the false, the incorruptible to the corruptible there is not even the capacity of friendship, unless a low view be taken of it to advance our interests, or enjoy passing pleasures which finally end in bitter disappointments and deep disgusts.

Moreover, there must be in lofty friendship not only congenial tastes, and an aspiration after the imperishable and true, but some common end which both parties strive to secure, and which they love better than they love themselves. Without this common end, friendship might wear itself out, or expend itself in things unworthy of an exalted purpose. Neither brilliant conversation, nor mutual courtesies, nor active sympathies will make social intercourse a perpetual charm. We tire of everything, at times, except the felicities of a pure and fervid love. But even husband and wife might tire without the common guardianship of children, or kindred zeal in some practical aims which both alike seek to secure; for they are helpmates as well as companions. Much more is it necessary for those who are not tied together in connubial bonds to have some common purpose in education, in philanthropy, in art, in religion. Such was pre-eminently the case with Paula and Jerome. They were equally devoted to a cause which was greater than themselves.

And this was the extension of monastic life, which in their day was the object of boundless veneration,–the darling scheme of the Church, indorsed by the authority of sainted doctors and martyrs, and resplendent in the glories of self-sacrifice and religious contemplation. At that time its subtile contradictions were not perceived, nor its practical evils developed. It was not a withered and cunning hag, but a chaste and enthusiastic virgin, rejoicing in poverty and self-denial, jubilant with songs of adoration, seeking the solution of mysteries, wrapt in celestial reveries, yet going forth from dreary cells to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, and still more, to give spiritual consolations to the poor and miserable. It was a great scheme of philanthropy, as well as a haven of rest. It was always sombre in its attire, ascetic in its habits, intolerant in its dogmas, secluded in its life, narrow in its views, and repulsive in its austerities; but its leaders and dignitaries did not then conceal under their coarse raiments either ambition, or avarice, or gluttony. They did not live in stately abbeys, nor ride on mules with gilded bridles, nor entertain people of rank and fashion, nor hunt heretics with fire and sword, nor dictate to princes in affairs of state, nor fill the world with spies, nor extort from wives the secrets of their husbands, nor peddle indulgences for sin, nor undermine morality by a specious casuistry, nor incite to massacres, insurrections, and wars. This complicated system of despotism, this Protean diversified institution of beggars and tyrants, this strange contradiction of glory in debasement and debasement in glory (type of the greatness and littleness of man), was not then matured, but was resplendent with virtues which extort esteem,–chastity, poverty, and obedience, devotion to the miserable, a lofty faith which spurned the finite, an unbounded charity amid the wreck of the dissolving world. As I have before said, it was a protest which perhaps the age demanded. The vow of poverty was a rebuke to that venal and grasping spirit which made riches the end of life; the vow of chastity was the resolution to escape that degrading sensuality which was one of the greatest evils of the times; and the vow of obedience was the recognition of authority amid the disintegrations of society. The monks would show that a cell could be the blessed retreat of learning and philosophy, and that even in a desert the soul could rise triumphant above the privations of the body, to the contemplation of immortal interests.

For this exalted life, as it seemed to the saints of the fourth century,–seclusion from a wicked world, leisure for study and repose, and a state favorable to Christian perfection,–both Paula and Jerome panted: he, that he might be more free to translate the Scriptures and write his commentaries, and to commune with God; she, to minister to his wants, stimulate his labors, enjoy the beatific visions, and set a proud example of the happiness to be enjoyed amid barren rocks or scorching sands. At Rome, Jerome was interrupted, diverted, disgusted. What was a Vanity Fair, a Babel of jargons, a school for scandals, a mart of lies, an arena of passions, an atmosphere of poisons, such as that city was, in spite of wonders of art and trophies of victory and contributions of genius, to a man who loved the certitudes of heaven, and sought to escape from the entangling influences which were a hindrance to his studies and his friendships? And what was Rome to an emancipated woman, who scorned luxuries and demoralizing pleasure, and who was perpetually shocked by the degradation of her sex even amid intoxicating social triumphs, by their devotion to frivolous pleasures, love of dress and ornament, elaborate hair-dressings, idle gossipings, dangerous dalliances, inglorious pursuits, silly trifles, emptiness, vanity, and sin? “But in the country,” writes Jerome, “it is true our bread will be coarse, our drink water, and our vegetables we must raise with our own hands; but sleep will not snatch us from agreeable discourse, nor satiety from the pleasures of study. In the summer the shade of the trees will give us shelter, and in the autumn the falling leaves a place of repose. The fields will be painted with flowers, and amid the warbling of birds we will more cheerfully chant our songs of praise.”

So, filled with such desires, and possessing such simplicity of tastes,–an enigma, I grant, to an age like ours, as indeed it may have been to his,–Jerome bade adieu to the honors and luxuries and excitements of the great city (without which even a Cicero languished), and embarked at Ostia, A.D. 385, for those regions consecrated by the sufferings of Christ. Two years afterwards, Paula, with her daughter, joined him at Antioch, and with a numerous party of friends made an extensive tour in the East, previous to a final settlement in Bethlehem. They were everywhere received with the honors usually bestowed on princes and conquerors. At Cyprus, Sidon, Ptolemais, Caesarea, and Jerusalem these distinguished travellers were entertained by Christian bishops, and crowds pressed forward to receive their benediction. The Proconsul of Palestine prepared his palace for their reception, and the rulers of every great city besought the honor of a visit. But they did not tarry until they reached the Holy Sepulchre, until they had kissed the stone which covered the remains of the Saviour of the world. Then they continued their journey, ascending the heights of Hebron, visiting the house of Mary and Martha, passing through Samaria, sailing on the lake Tiberias, crossing the brook Cedron, and ascending the Mount of Transfiguration. Nor did they rest with a visit to the sacred places hallowed by associations with kings and prophets and patriarchs. They journeyed into Egypt, and, by the route taken by Joseph and Mary in their flight, entered the sacred schools of Alexandria, visited the cells of Nitria, and stood beside the ruins of the temples of the Pharaohs.

A whole year was thus consumed by this illustrious party,–learning more than they could in ten years from books, since every monument and relic was explained to them by the most learned men on earth. Finally they returned to Bethlehem, the spot which Jerome had selected for his final resting-place, and there Paula built a convent near to the cell of her friend, which she caused to be excavated from the solid rock. It was there that he performed his mighty literary labors, and it was there that his happiest days were spent. Paula was near, to supply his simple wants, and give, with other pious recluses, all the society he required. He lived in a cave, it is true, but in a way afterwards imitated by the penitent heroes of the Fronde in the vale of Chevreuse; and it was not disagreeable to a man sickened with the world, absorbed in literary labors, and whose solitude was relieved by visits from accomplished women and illustrious bishops and scholars. Fabiola, with a splendid train, came from Rome to listen to his wisdom. Not only did he translate the Bible and write commentaries, but he resumed his pious and learned correspondence with devout scholars throughout the Christian world. Nor was he too busy to find time to superintend the studies of Paula in Greek and Hebrew, and read to her his most precious compositions; while she, on her part, controlled a convent, entertained travellers from all parts of the world, and diffused a boundless charity,–for it does not seem that she had parted with the means of benefiting both the poor and the rich.

Nor was this life at Bethlehem without its charms. That beautiful and fertile town,–as it then seems to have been,–shaded with sycamores and olives, luxurious with grapes and figs, abounding in wells of the purest water, enriched with the splendid church that Helena had built, and consecrated by so many associations, from David to the destruction of Jerusalem, was no dull retreat, and presented far more attractions than did the vale of Port Royal, where Saint Cyran and Arnauld discoursed with the Mère Angelique on the greatness and misery of man; or the sunny slopes of Cluny, where Peter the Venerable sheltered and consoled the persecuted Abélard. No man can be dull when his faculties are stimulated to their utmost stretch, if he does live in a cell; but many a man is bored and ennuied in a palace, when he abandons himself to luxury and frivolities. It is not to animals, but to angels, that the higher life is given.

Nor during those eighteen years which Paula passed in Bethlehem, or the previous sixteen years at Rome, did ever a scandal rise or a base suspicion exist in reference to the friendship which has made her immortal. There was nothing in it of that Platonic sentimentality which marked the mediaeval courts of love; nor was it like the chivalrous idolatry of flesh and blood bestowed on queens of beauty at a tournament or tilt; nor was it poetic adoration kindled by the contemplation of ideal excellence, such as Dante saw in his lamented and departed Beatrice; nor was it mere intellectual admiration which bright and enthusiastic women sometimes feel for those who dazzle their brains, or who enjoy a great éclat; still less was it that impassioned ardor, that wild infatuation, that tempestuous frenzy, that dire unrest, that mad conflict between sense and reason, that sad forgetfulness sometimes of fame and duty, that reckless defiance of the future, that selfish, exacting, ungovernable, transient impulse which ignores God and law and punishment, treading happiness and heaven beneath the feet,–such as doomed the greatest genius of the Middle Ages to agonies more bitter than scorpions’ stings, and shame that made the light of heaven a burden; to futile expiations and undying ignominies. No, it was none of these things,–not even the consecrated endearments of a plighted troth, the sweet rest of trust and hope, in the bliss of which we defy poverty, neglect, and hardship; it was not even this, the highest bliss of earth, but a sentiment perhaps more rare and scarcely less exalted,–that which the apostle recognized in the holy salutation, and which the Gospel chronicles as the highest grace of those who believed in Jesus, the blessed balm of Bethany, the courageous vigilance which watched beside the tomb.

But the time came–as it always must–for the sundering of all earthly ties; austerities and labors accomplished too soon their work. Even saints are not exempted from the penalty of violated physical laws. Pascal died at thirty-seven. Paula lingered to her fifty-seventh year, worn out with cares and vigils. Her death was as serene as her life was lofty; repeating, as she passed away, the aspirations of the prophet-king for his eternal home. Not ecstasies, but a serene tranquillity, marked her closing hours. Raising her finger to her lip, she impressed upon it the sign of the cross, and yielded up her spirit without a groan. And the icy hand of death neither changed the freshness of her countenance nor robbed it of its celestial loveliness; it seemed as if she were in a trance, listening to the music of angelic hosts, and glowing with their boundless love. The Bishop of Jerusalem and the neighboring clergy stood around her bed, and Jerome closed her eyes. For three days numerous choirs of virgins alternated in Greek, Latin, and Syriac their mournful but triumphant chants. Six bishops bore her body to the grave, followed by the clergy of the surrounding country. Jerome wrote her epitaph in Latin, but was too much unnerved to preach her funeral sermon. Inhabitants from all parts of Palestine came to her funeral: the poor showed the garments which they had received from her charity; while the whole multitude, by their sighs and tears, evinced that they had lost a nursing mother. The Church received the sad intelligence of her death with profound grief, and has ever since cherished her memory, and erected shrines and monuments to her honor. In that wonderful painting of Saint Jerome by Domenichino,–perhaps the greatest ornament of the Vatican, next to that miracle of art, the “Transfiguration” of Raphael,–the saint is represented in repulsive aspects as his soul was leaving his body, ministered unto by the faithful Paula. But Jerome survived his friend for fifteen years, at Bethlehem, still engrossed with those astonishing labors which made him one of the greatest benefactors of the Church, yet austere and bitter, revealing in his sarcastic letters how much he needed the soothing influences of that sister of mercy whom God had removed to the choir of angels, and to whom the Middle Ages looked as an intercessor, like Mary herself, with the Father of all, for the pardon of sin.

But I need not linger on Paula’s deeds of fame. We see in her life, pre-eminently, that noble sentiment which was the first development in woman’s progress from the time that Christianity snatched her from the pollution of Paganism. She is made capable of friendship for man without sullying her soul, or giving occasion for reproach. Rare and difficult as this sentiment is, yet her example has proved both its possibility and its radiance. It is the choicest flower which a man finds in the path of his earthly pilgrimage. The coarse-minded interpreter of a woman’s soul may pronounce that rash or dangerous in the intercourse of life which seeks to cheer and assist her male associates by an endearing sympathy; but who that has had any great literary or artistic success cannot trace it, in part, to the appreciation and encouragement of those cultivated women who were proud to be his friends? Who that has written poetry that future ages will sing; who that has sculptured a marble that seems to live; who that has declared the saving truths of an unfashionable religion,–has not been stimulated to labor and duty by women with whom he lived in esoteric intimacy, with mutual admiration and respect?

Whatever the heights to which woman is destined to rise, and however exalted the spheres she may learn to fill, she must remember that it was friendship which first distinguished her from Pagan women, and which will ever constitute one of her most peerless charms. Long and dreary has been her progress from the obscurity to which even the Middle Ages doomed her, with all the boasted admiration of chivalry, to her present free and exalted state. She is now recognized to be the equal of man in her intellectual gifts, and is sought out everywhere as teacher and as writer. She may become whatever she pleases,–actress, singer, painter, novelist, poet, or queen of society, sharing with man the great prizes bestowed on genius and learning. But her nature cannot be half developed, her capacities cannot be known, even to herself, until she has learned to mingle with man in the free interchange of those sentiments which keep the soul alive, and which stimulate the noblest powers. Then only does she realize her aesthetic mission. Then only can she rise in the dignity of a guardian angel, an educator of the heart, a dispenser of the blessings by which she would atone for the evil originally brought upon mankind. Now, to administer this antidote to evil, by which labor is made sweet, and pain assuaged, and courage fortified, and truth made beautiful, and duty sacred,–this is the true mission and destiny of woman. She made a great advance from the pollutions and slaveries of the ancient world when she proved herself, like Paula, capable of a pure and lofty friendship, without becoming entangled in the snares and labyrinths of an earthly love; but she will make a still greater advance when our cynical world shall comprehend that it is not for the gratification of passing vanity, or foolish pleasure, or matrimonial ends that she extends her hand of generous courtesy to man, but that he may be aided by the strength she gives in weakness, encouraged by the smiles she bestows in sympathy, and enlightened by the wisdom she has gained by inspiration.

Authorities.

Butler’s Lives of the Saints; Epistles of Saint Jerome; Cave’s Lives of the Fathers; Dolci’s De Rebus Gestis Hieronymi; Tillemont’s Ecclesiastical History; Gibbon’s Decline and Fall; Neander’s Church History. See also Henry and Dupin. One must go to the Catholic historians, especially the French, to know the details of the lives of those saints whom the Catholic Church has canonized. Of nothing is Protestant ecclesiastical history more barren than the heroism, sufferings, and struggles of those great characters who adorned the fourth and fifth centuries, as if the early ages of the Church have no interest except to Catholics.