Theodosius the Great : Latter Days of Rome – Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

Cyrus the Great : Asiatic Supremacy

Julius Caesar : Imperialism

Marcus Aurelius : Glory of Rome

Constantine the Great : Christianity Enthroned

Paula : Woman as Friend

Chrysostom : Sacred Eloquence

Saint Ambrose : Episcopal Authority

Saint Augustine : Christian Theology

Theodosius the Great : Latter Days of Rome

Leo the Great : Foundation of the Papacy

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

The mission of Theodosius

General sense of security in the Roman world

The Romans awake from their delusion

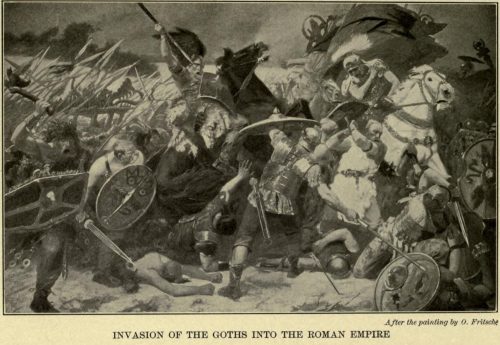

Incursions of the Goths

Battle of Adrianople; death of Valens

Necessity for a great deliverer to arise; Theodosius

The Goths,–their characteristics and history

Elevation of Theodosius as Associate Emperor

He conciliates the Goths, and permits them to settle in the Empire

Revolt of Maximus against Gratian; death of Gratian

Theodosius marches against Maximus and subdues him

Revolt of Arbogastes,–his usurpation

Victories of Theodosius over all his rivals; the Empire once more united under a single man

Reforms of Theodosius; his jurisprudence

Patronage of the clergy and dignity of great ecclesiastics

Theodosius persecutes the Arians

Extinguishes Paganism and closes the temples

Cements the union of Church with State

Faults and errors of Theodosius; massacre of Thessalonica

Death of Theodosius

Division of the Empire between his two sons

Renewed incursions of the Goths,–Alaric; Stilicho

Fall of Rome; Genseric and the Vandals

Second sack of Rome

Reflections on the Fall of the Western Empire

Theodosius the Great : Latter Days of Rome

A.D. 346-395.

The last of those Roman emperors whom we call great was Theodosius. After him there is no great historic name, unless it be Justinian, who reigned when Rome had fallen. With Theodosius is associated the life-and-death struggle of Rome with the Gothic barbarians, and the final collapse of Paganism as a tolerated religion. Paganism in its essence, its spirit, was not extinguished; it entered into new forms, even into the Church itself; and it still exists in Christian countries. When Bismarck was asked why he did not throw down his burdens, he is reported to have said: “Because no man can take my place. I should like to retire to my estates and raise cabbages; but I have work to do against Paganism: I live among Pagans.” Neither Theodosius nor Bismarck was what we should call a saint. Both have been stained by acts which it is hard to distinguish from crimes; but both have given evidence of hatred of certain evils which undermine society. Theodosius, especially, made war and fought nobly against the two things which most imperilled the Empire,–the barbarians who had begun their ravages, and the Paganism which existed both in and outside the Church. For which reasons he has been praised by most historians, in spite of great crimes and some vices. The worldly Gibbon admires him for the noble stand he took against external dangers, and the Fathers of the Church almost adored him for his zealous efforts in behalf of orthodoxy. An eminent scholar of the advanced school has seen nothing in him to admire, and much to blame. But he was undoubtedly a very great man, and rendered important services to his age and to civilization, although he could not arrest the fatal disease which even then had destroyed the vitality of the Empire. It was already doomed when he ascended the throne. No mortal genius, no imperial power, could have saved the crumbling Empire.

In my lecture on Marcus Aurelius I alluded to the external prosperity and internal weakness of the old Roman world during his reign. That outward prosperity continued for a century after he was dead,–that is, there were peace, thrift, art, wealth, and splendor. Men were unmolested in the pursuit of pleasure. There were no great wars with enemies beyond the limits of the Empire. There were wars of course; but these chiefly were civil wars between rival aspirants for imperial power, or to suppress rebellions, which did not alarm the people. They still sat under their own vines and fig-trees, and danced to voluptuous music, and rejoiced in the glory of their palaces. They feasted and married and were given in marriage, like the antediluvians. They never dreamed that a great catastrophe was near, that great calamities were impending.

I do not say that the people in that century were happy or contented, or even generally prosperous. How could they be happy or prosperous when monsters and tyrants sat on the throne of Augustus and Trajan? How could they be contented when there was such a vast inequality of condition,–when slaves were more numerous than freemen,–when most of the women were guarded and oppressed,–when scarcely a man felt secure of the virtue of his wife, or a wife of the fidelity of her husband,–when there was no relief from corroding sorrows but in the sports of the amphitheatre and circus, or some form of demoralizing excitement or public spectacle,–when the great mass were ground down by poverty and insult, and the few who were rich and favored were satiated with pleasure, ennuéd, and broken down by dissipation,–when there was no hope in this world or in the next, no true consolation in sickness or in misfortune, except among the Christians, who fled by thousands to desert places to escape the contaminating vices of society?

But if the people were not happy or fortunate as a general thing, they anticipated no overwhelming calamities; the outward signs of prosperity remained,–all the glories of art, all the wonders of imperial and senatorial magnificence; the people were fed and amused at the expense of the State; the colosseum was still daily crowded with its eighty-seven thousand spectators, and large hogs were still roasted whole at senatorial banquets, and wines were still drunk which had been stored one hundred years. The “dark-skinned daughters of Isis” still sported unmolested in wanton mien with the priests of Cybele in their discordant cries. The streets still were filled with the worshippers of Bacchus and Venus, with barbaric captives and their Teuton priests, with chariots and horses, with richly apparelled young men, and fashionable ladies in quest of new perfumes. The various places of amusement were still thronged with giddy youth and gouty old men who would have felt insulted had any one told them that the most precious thing they had was the most neglected. Everywhere, as in the time of Trajan, were unrestricted pleasures and unrestricted trades. What cared the shopkeepers and the carpenters and the bakers whether a Commodus or a Severus reigned? They were safe. It was only great nobles who were in danger of being robbed or killed by grasping emperors. The people, on the whole, lived for one hundred years after the accession of Commodus as they did under Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. True, there had been great calamities during this hundred years. There had been terrible plagues and pestilences: in some of these as many as five thousand people died daily in Rome alone. There were tumults and revolts; there were wars and massacres; there was often the reign of monsters or idiots. Yet even as late as the reign of Aurelian, ninety years after the death of Aurelius, the Empire was thought to be eternal; nor was any triumph ever celebrated with greater pride and magnificence than his. And as the victorious emperor in his triumphal chariot marched along the Via Sacra up the Capitoline hill, with the spoils and trophies of one hundred battles, with ambassadors and captives, including Zenobia herself, fainting with the weight of jewels and golden fetters, it would seem that Rome was destined to overcome all the vicissitudes of Nature, and reign as mistress of the world forever.

But that century did not close until real dangers stared the people in the face, and so alarmed the guardians of the Empire that they no longer could retire to their secluded villas for luxurious leisure, but were forced to perpetual warfare, and with foes they had hitherto despised.

Two things marked the one hundred years before the accession of Theodosius of especial historical importance,–the successful inroads of barbarians carrying desolation and alarm to the very heart of the Empire; and the wonderful spread of the Christian religion. Persecution ended with Diocletian; and under Constantine Christianity seated herself upon his throne. During this century of barbaric spoliations and public miseries,–the desolation of provinces, the sack of cities, the ruin of works of art, the burning of palaces, all the unnumbered evils which universal war created,–the converts to Christianity increased, for Christianity alone held out hope amid despair and ruin. The public dangers were so great that only successful generals were allowed to wear the imperial purple.

The ablest men of the Empire were at last summoned to govern it. From the year 268 to 394 most of the emperors were able men, and some were great and virtuous. Perhaps the Empire was never more ably administered than was the Roman in the day of its calamities. Aurelian, Diocletian, Constantine, Theodosius, are alike immortal. They all alike fought with the same enemies, and contended with the same evils. The enemies were the Gothic barbarians; the evils were the degeneracy and vices of Roman soldiers, which universal corruption had at last produced. It was a sad hour in the old capital of the world when its blinded inhabitants were aroused from the stupendous delusion that they were invincible; when the crushing fact blazed upon them that the legions had been beaten, that province after province had been overrun, that the proudest cities had fallen, that the barbarians were advancing,–everywhere advancing,–treading beneath their feet temples, palaces, statues, libraries, priceless works of art; that there was no shelter to which they could fly; that Rome herself was doomed. In the year 378 the Emperor Valens himself was slain, almost under the walls of his capital, with two-thirds of his army,–some sixty thousand infantry and six thousand cavalry,–while the victorious Goths, gorged with spoils, advanced to take possession of the defeated and crumbling Empire. From the shores of the Bosporus to the Julian Alps nothing was seen but conflagration, murders, and depredations, and the cry of anguish went up to heaven in accents of almost universal despair.

In such a crisis a great man was imperatively needed, and a great man arose. The dismayed emperor cast his eyes over the whole extent of his dominions to find a deliverer. And he found the needed hero living quietly and in modest retirement on a farm in Spain. This man was Theodosius the Great, a young man then,–as modest as David amid the pastures, as unambitious as Cincinnatus at the plough. “The vulgar,” says Gibbon, “gazed with admiration on the manly beauty of his face and the graceful majesty of his person, while in the qualities of his mind and heart intelligent observers perceived the blended excellences of Trajan and Constantine.” As prudent as Fabius, as persevering as Alfred, as comprehensive as Charlemagne, as full of resources as Frederic II., no more fitting person could be found to wield the sceptre of Trajan his ancestor. No greater man than he did the Empire then contain, and Gratian was wise and fortunate in associating with himself so illustrious a man in the imperial dignity.

If Theodosius was unassuming, he was not obscure and unimportant. His father had been a successful general in Britain and Africa, and he himself had been instructed by his father in the art of war, and had served under him with distinction. As Duke of Maesia he had vanquished an army of Sarmatians, saved the province, deserved the love of his soldiers, and provoked the envy of the court. But his father having incurred the jealousy of Gratian and been unjustly executed, he was allowed to retire to his patrimonial estates near Valladolid, where he gave himself up to rural enjoyments and ennobling studies. He was not long permitted to remain in this retirement; for the public dangers demanded the service of the ablest general in the Empire, and there was no one so illustrious as he. And how lofty must have been his character, if Gratian dared to associate with himself in the government of the Empire a man whose father he had unjustly executed! He was thirty-three when he was invested with imperial purple and intrusted with the conduct of the Gothic war.

The Goths, who under Fritigern had defeated the Roman army before the walls of Adrianople, were Germanic barbarians who lived between the Rhine and the Vistula in those forests which now form the empire of Germany. They belonged to a family of nations which had the same natural characteristics,–love of independence, passion for war, veneration for women, and religious tendency of mind. They were brave, persevering, bold, hardy, and virtuous, for barbarians. They cast their eyes on the Roman provinces in the time of Marius, and were defeated by him under the name of Teutons. They had recovered strength when Caesar conquered the Gauls. They were very formidable in the time of Marcus Aurelius, and had formed a general union for the invasion of the Roman world. But a barrier had been made against their incursions by those good and warlike emperors who preceded Commodus, so that the Romans had peace for one hundred years. These barbarians went under different names, which I will not enumerate,–different tribes of the same Germanic family, whose remote ancestors lived in Central Asia and were kindred to the Medes and Persians. Like the early inhabitants of Greece and Italy, they were of the Aryan race. All the members of this great family, in their early history, had the same virtues and vices. They worshipped the forces of Nature, recognizing behind these a supreme and superintending deity, whose wrath they sought to deprecate by sacrifices. They set a great value on personal independence, and hence had great individuality of character. They delighted in the pleasures of the chase. They were generally temperate and chaste. They were superstitious, social, and quarrelsome, bent on conquest, and migrated from country to country with a view of improving their fortunes.

The Goths were the first of these barbarians who signally triumphed over the Roman arms. “Starting from their home in the Scandinavian peninsula, they pressed upon the Slavic population of the Vistula, and by rapid conquests established themselves in southern and eastern Germany. Here they divided. The Visi or West Goths advanced to the Danube.” In the reign of Decius (249-251) they crossed the river and ravaged the Roman territory. In 269 they imposed a tribute on the Emperor Gratian, and seem to have been settled in Dacia. After this they made several successful raids,–invading Bythinia, entering the Propontis, and advancing as far as Athens and Corinth, even to the coasts of Asia Minor; destroying in their ravages the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, with its one hundred and twenty-seven marble columns.

These calamities happened in the middle of the third century, during the reign of the frivolous Gallienus, who received the news with his accustomed indifference. While the Goths were burning the Grecian cities, this royal cook and gardener was soliciting a place in the Areopagus of Athens.

In the reign of Claudius the barbarians united under the Gothic standard, and in six thousand vessels prepared again to ravage the world. Against three hundred and twenty thousand of these Goths Claudius advanced, and defeated them at Naissus in Dalmatia. Fifty thousand were slain, and three Gothic women fell to the share of every soldier. On the return of spring nothing of that mighty host was seen. Aurelian–who succeeded Claudius, and whose father had been a peasant of Sirmium–put an end to the Gothic war, and the Empire again breathed; but only for a time, for the barbarians continually advanced, although they were continually beaten by the warlike emperors who succeeded Gallienus. In the middle of the third century they were firmly settled in Dacia, by permission of Valerian. One hundred years after, pressed by Huns, they asked for lands south of the Danube, which request was granted by Valens; but they were rudely treated by the Roman officials, especially their women, and treachery was added to their other wrongs. Filled with indignation, they made a combination and swept everything before them,–plundering cities, and sparing neither age nor sex. These ravages continued for a year. Valens, aroused, advanced against them, and was slain in the memorable battle on the plains of Adrianople, 9th of August, 378,–the most disastrous since the battle of Cannae, and from which the Empire never recovered.

To save the crumbling world, Theodosius was now made associate emperor. And in that great crisis prudence was more necessary than valor. No Roman army at that time could contend openly in the field, face to face, with the conquering hordes who assembled under the standard of Fritigern,–the first historic name among the Visigoths. Theodosius “fixed his headquarters at Thessalonica, from whence he could watch the irregular actions of the barbarians and direct the movements of his lieutenants.” He strengthened his defences and fortifications, from which his soldiers made frequent sallies,–as Alfred did against the Danes,–and accustomed themselves to the warfare of their most dangerous enemies. He pursued the same policy that Fabius did after the battle of Cannae, to whose wisdom the Romans perhaps were more indebted for their ultimate success than to the brilliant exploits of Scipio. The death of Fritigern, the great predecessor of Alaric, relieved Theodosius from many anxieties; for it was followed by the dissension and discord of the barbarians themselves, by improvidence and disorderly movements; and when the Goths were once more united under Athanaric, Theodosius succeeded in making an honorable treaty with him, and in entertaining him with princely hospitalities in his capital, whose glories alike astonished and bewildered him. Temperance was not one of the virtues of Gothic kings under strong temptation, and Athanaric, yielding to the force of banquets and imperial seductions, soon after died. The politic emperor gave his late guest a magnificent funeral, and erected to his memory a stately monument; which won the favor of the Goths, and for a time converted them to allies. In four years the entire capitulation of the Visigoths was effected.

Theodosius then turned his attention to the Ostro or East Goths, who advanced, with other barbarians, to the banks of the lower Danube, on the Thracian frontier. Allured to cross the river in the night, the barbarians found a triple line of Roman war-vessels chained to each other in the middle of the river, which offered an effectual resistance to their six thousand canoes, and they perished with their king.

Having gradually vanquished the most dangerous enemies of the Empire, Theodosius has been censured for allowing them to settle in the provinces they had desolated, and still more for incorporating fifty thousand of their warriors in the imperial armies, since they were secret enemies, and would burst through their limits whenever an opportunity offered. But they were really too formidable to be driven back beyond the frontiers of the crumbling Empire. Theodosius could only procure a period of peace; and this was not to be secured save by adroit flatteries. The day was past for the extermination of the Goths by Roman soldiers, who had already thrown away their defensive armor; nor was it possible that they would amalgamate with the people of the Empire, as the Celtic barbarians had done in Spain and Gaul after the victories of Caesar. Though the kingly power was taken away from them and they fought bravely under the imperial standards, it was evident from their insolence and their contempt of the effeminate masters that the day was not distant when they would be the conquerors of the Empire. It does not speak well for an empire that it is held together by the virtues and abilities of a single man. Nor could the fate of the Roman empire be doubtful when barbarians were allowed to settle in its provinces; for after the death of Valens the Goths never abandoned the Roman territory. They took possession of Thrace, as Saxons and Danes took possession of England.

After the conciliation of the Goths,–for we cannot call it the conquest,–Theodosius was obliged to turn his attention to the affairs of the Western Empire; for he ruled only the Eastern provinces. It would seem that Gratian, who had called him to his assistance to preserve the East from the barbarians, was now in trouble in the West. He had not fulfilled the great expectation that had been formed of him. He degraded himself in the eyes of the Romans by his absorbing passion for the pleasures of the chase; while public affairs imperatively demanded his attention. He received a body of Alans into the military and domestic service of the palace. He was indolent and pleasure-seeking, but was awakened from his inglorious sports by a revolt in Britain. Maximus, a native of Spain and governor of the island, had been proclaimed emperor by his soldiers. He invaded Gaul with a large fleet and army, followed by the youth of Britain, and was received with acclamations by the armies of that province. Gratian, then residing in Paris, fled to Lyons, deserted by his troops, and was assassinated by the orders of Maximus. The usurper was now acknowledged by the Western provinces as emperor, and was too powerful to be resisted at that time by Theodosius, who accepted his ambassadors, and made a treaty with the usurper by which he was permitted to reign over Britain, Gaul, and Spain, provided that the other Western provinces, including Wales, should accept and acknowledge Valentinian, the brother of the murdered Gratian, who was however a mere boy, and was ruled by his mother Justina, an Arian,–that celebrated woman who quarrelled with Ambrose, archbishop of Milan. Valentinian was even more feeble than Gratian, and Maximus, not contented with the sovereignty of the three most important provinces of the Empire, resolved to reign over the entire West. Theodosius, who had dissembled his anger and waited for opportunity, now advanced to the relief of Valentinian, who had been obliged to fly from Milan,–the seat of his power. But in two months Theodosius subdued his rival, who fled to Italy, only, however, to be dragged from the throne and executed.

Having terminated the civil war, and after a short residence in Milan, Theodosius made his triumphal entry into the ancient capital of the world. He was now the absolute and undisputed master of the East and the West, as Constantine had been, whom he resembled in his military genius and executive ability; but he gave to Valentinian (a youth of twenty, murdered a few months after) the provinces of Italy and Illyria, and intrusted Gaul to the care of Arbogastes,–a gallant soldier among the Franks, who, like Maximus, aspired to reign. But power was dearer to the valiant Frank than a name; and he made his creature, the rhetorician Eugenius, the nominal emperor of the West. Hence another civil war; but this more serious than the last, and for which Theodosius was obliged to make two years’ preparation. The contest was desperate. Victory at one time seemed even to be on the side of Arbogastes: Theodosius was obliged to retire to the hills on the confines of Italy, apparently subdued, when, in the utmost extremity of danger, a desertion of troops from the army of the triumphant barbarian again gave him the advantage, and the bloody and desperate battle on the banks of the Frigidus re-established Theodosius as the supreme ruler of the world. Both Arbogastes and Eugenius were slain, and the East and West were once more and for the last time united. The division of the Empire under Diocletian had not proved a wise policy, but was perhaps necessary; since only a Hercules could have borne the burdens of undivided sovereignty in an age of turbulence, treason, revolts, and anarchies. It was probably much easier for Tiberius or Trajan to rule the whole world than for one of the later emperors to rule a province. Alfred had a harder task than Charlemagne, and Queen Elizabeth than Queen Victoria.

I have dwelt very briefly on those contests in which the great Theodosius was obliged to fight for his crown and for the Empire. For a time he had delivered the citizens from the fear of the Goths, and had re-established the imperial sovereignty over the various provinces. But only for a time. The external dangers reappeared at his death. He only averted impending ruin; he only propped up a crumbling Empire. No human genius could have long prevented the fall. Hence his struggles with barbarians and with rebels have no deep interest to us. We associate with his reign something more important than these outward conflicts. Civilization at large owes him a great debt for labors in another field, for which he is most truly immortal,–for which his name is treasured by the Church,–for which he was one of the great benefactors.

These labors were directed to the improvement of jurisprudence, and the final extinction of Paganism as a tolerated religion. He gave to the Church and to Christianity a new prestige. He rooted out, so far as genius and authority can, those heresies which were rapidly assimilating the new religion to the old. He was the friend and patron of those great ecclesiastics whose names are consecrated. The great Ambrose was his special friend, in whose arms he expired. Augustine, Martin of Tours, Jerome, Gregory Nazianzen, Basil, Chrysostom, Damasus, were all contemporaries, or nearly so. In his day the Church was really seated on the high-places of the earth. A bishop was a greater man than a senator; he exercised more influence and had more dignity than a general. He was ambassador, courtier, and statesman, as well as prelate. Theodosius handed over to the Church the government of mankind. To him we date that ecclesiastical government which was perfected by Charlemagne, and which was dominant in the Middle Ages. Anarchy and misery spread over the world; but the new barbaric forces were obedient to the officers of the Church. The Church looms up in the days of Theodosius as the great power of the world.

Theodosius is lauded as a Christian prince even more than Constantine, and as much as Alfred. He was what is called orthodox, and intensely so. He saw in Arianism a heresy fatal to the Church. “It is our pleasure,” said he, “that all nations should steadfastly adhere to the religion which was taught by Saint Peter to the Romans, which is the sole Deity of the Father, the Son, and Holy Ghost, under an equal majesty; and we authorize the followers of this doctrine to assume the title of Catholic Christians.” If Rome under Damasus and the teachings of Jerome was the seat of orthodoxy, Constantinople was the headquarters of Arianism. We in our times have no conception of the interest which all classes took in the metaphysics of theology. Said one of the writers of the day: “If you desire a man to change a piece of silver, he informs you wherein the Son differs from the Father; if you ask the price of a loaf, you are told in reply that the Son is inferior to the Father; if you inquire whether the bath is ready, the answer is that the Son was made out of nothing.” The subtle questions pertaining to the Trinity were the theme of universal conversation, even amid the calamities of the times.

Theodosius, as soon as he had finished his campaign against the Goths, summoned the Arian archbishop of Constantinople, and demanded his subscription to the Nicene Creed or his resignation. It must be remembered that the Arians were in an overwhelming majority in the city, and occupied the principal churches. They complained of the injustice of removing their metropolitan, but the emperor was inflexible; and Gregory Nazianzen, the friend of Basil, was promoted to the vacant See, in the midst of popular grief and rage. Six weeks afterwards Theodosius expelled from all the churches of his dominions, both of bishops and of presbyters, those who would not subscribe to the Nicene Creed. It was a great reformation, but effected without bloodshed.

Moreover, in the year 381 he assembled a general council of one hundred and fifty bishops at his capital, to finish the work of the Council of Nice, and in which Arianism was condemned. In the space of fifteen years seven imperial edicts were fulminated against those who maintained that the Son was inferior to the Father. A fine equal to two thousand dollars was imposed on every person who should receive or promote an Arian ordination. The Arians were forbidden to assemble together in their churches, and by a sort of civil excommunication they were branded with infamy by the magistrates, and rendered incapable of civil offices of trust and emolument. Capital punishment even was inflicted on Manicheans.

So it would appear that Theodosius inaugurated religious persecution for honest opinions, and his edicts were similar in spirit to those of Louis XIV. against the Protestants,–a great flaw in his character, but for which he is lauded by the Catholic historians. The eloquent Fléchier enlarges enthusiastically on the virtues of his private life, on his chastity, his temperance, his friendship, his magnanimity, as well as his zeal in extinguishing heresy. But for him, Arianism might possibly have been the established religion of the Empire, since not only the dialectical Greeks, but the sensuous Goths, inclined to that creed. Ulfilas, in his conversion of those barbarians, had made them the supporters of Arianism, not because they understood the subtile distinctions which theologians had made, but because it was the accepted and fashionable faith of Constantinople. Spain, however, through the commanding influence of Hosius, adhered to the doctrines of Athanasius, while the eloquence of the commanding intellects of the age was put forth in behalf of Trinitarianism. The great leader of Arianism had passed away when Augustine dictated to the Christian world from the little town of Hippo, and Jerome transplanted the monasticism of the East into the West. At Tours Martin defended the same cause that Augustine had espoused in Africa; while at Milan, the court capital of the West, the venerable Ambrose confirmed Italy in the Latin creed. In Alexandria the fierce Theophilus suppressed Arianism with the same weapons that he had used in extirpating the worship of Isis and Osiris. Chrysostom at Antioch was the equally strenuous advocate of the Athanasian Creed. We are struck with the appearance of these commanding intellects in the last days of the Empire,–not statesmen and generals, but ecclesiastics and churchmen, generally agreed in the interpretation of the faith as declared by Paul, and through whose counsels the emperor was unquestionably governed. In all matters of religion Theodosius was simply the instrument of the great prelates of the age,–the only great men that the age produced.

After Theodosius had thus established the Nicene faith, so far as imperial authority, in conjunction with that of the great prelates, could do so, he closed the final contest with Paganism itself. His laws against Pagan sacrifices were severe. It was death to inspect the entrails of victims for sacrifice; and all other sacrifices, in the year 392, were made a capital offence. He even demolished the Pagan temples, as the Scots destroyed the abbeys and convents which were the great monuments of Mediaeval piety. The revenues of the temples were confiscated. Among the great works of ancient art which were destroyed, but might have been left or converted into Christian use, were the magnificent temple of Edessa and the serapis of Alexandria, uniting the colossal grandeur of Egyptian with the graceful harmony of Grecian art. At Rome not only was the property of the temples confiscated, but also all privileges of the priesthood. The Vestal virgins passed unhonored in the streets. Whoever permitted any Pagan rite–even the hanging of a chaplet on a tree–forfeited his estate. The temples of Rome were not destroyed, as in Syria and Egypt; but as all their revenues were confiscated, public worship declined before the superior pomps of a sensuous and even idolatrous Christianity. The Theodosian code, published by Theodosius the Younger, A.D. 438, while it incorporated Christian usages and laws in the legislation of the Empire, did not, however, disturb the relation of master and slave; and when the Empire fell, slavery still continued as it was in the times of Augustus and Diocletian. Nor did Christianity elevate imperial despotism into a wise and beneficent rule. It did not change perceptibly the habits of the aristocracy. The most vivid picture we have of the vices of the leading classes of Roman society are painted by a contemporaneous Pagan historian,–Ammianus Marcellinus,–and many a Christian matron adorned herself with the false and colored hair, the ornaments, the rouge, and the silks of the Pagan women of the time of Cleopatra. Never was luxury more enervating, or magnificence more gorgeous, but without refinement, than in the generation that preceded the fall of Rome. And coexistent with the vices which prepared the way for the conquests of the barbarians was the wealth of the Christian clergy, who vied with the expiring Paganism in the splendor of their churches, in the ornaments of their altars, and in the imposing ceremonial of their worship. The bishop became a great worldly potentate, and the strictest union was formed between the Church and State. The greatest beneficent change which the Church effected was in relation to divorce,–the facility for which disgraced the old Pagan civilization; but Christianity invested marriage with the utmost solemnity, so that it became a holy and indissoluble sacrament,–to which the Catholic Church, in the days of deepest degeneracy has ever clung, leaving to the Protestants the restoration of this old Pagan custom of divorce, as well as the encouragement and laudation of a material civilization.

The spirit of Paganism never has been exorcised in any age of Christian progress and triumph, but has appeared from time to time in new forms. In the conquering Church of Constantine and Theodosius it adopted Pagan emblems and gorgeous rites and ceremonies; in the Middle Ages it appeared in the dialectical contests of the Greek philosophers; in our times in the deification of the reason, in the apotheosis of art, in the inordinate value placed on the enjoyments of the body, and in the splendor of an outside life. Names are nothing. To-day we are swinging to the Epicurean side of the Greeks and Romans as completely as they did in the age of Commodus and Aurelian; and none may dare to hurl their indignant protests without meeting a neglect and obloquy sometimes more hard to bear than the persecutions of Nero, of Trajan, of Leo X., of Louis XIV.

If Theodosius were considered aside from his able administration of the Empire and his patronage of the orthodox leaders of the Church, he would be subject to severe criticism. He was indolent, irascible, and severe. His name and memory are stained by a great crime,–the slaughter of from seven to fifteen thousand of the people of Thessalonica,–one of the great crimes of history, but memorable for his repentance more than for his cruelty. Had Theodosius not submitted to excommunication and penance, and given every sign of grief and penitence for this terrible deed, he would have passed down in history as one of the cruellest of all the emperors, from Nero downwards; for nothing can excuse, or even palliate, so gigantic a crime, which shocked the whole civilized world,–a crime more inexcusable than the slaughter of Saint Bartholomew or the massacre which followed the revocation of the edict of Nantes.

Theodosius survived that massacre about five years, and died at Milan, 395, at the age of fifty, from a disease which was caused by the fatigues of war, which, with a constitution undermined by self-indulgence, he was unable to bear. But whatever the cause of his death it was universally lamented, not from love of him so much as from the sense of public dangers which he alone had the power to ward off. At his death his Empire was divided between his two feeble sons,–Honorius and Arcadius, and the general ruin which everybody began to fear soon took place. After Theodosius, no great and warlike sovereign reigned over the crumbling and dismembered Empire, and the ruin was as rapid as it was mournful.

The Goths, released from the restraints and fears which Theodosius imposed, renewed their ravages; and the effeminate soldiers of the Empire, who formerly had marched with a burden of eighty pounds, now threw away the heavy weapons of their ancestors, even their defensive armor, and of course made but feeble resistance. The barbarians advanced from conquering to conquer. Alaric, leader of the Goths, invaded Greece at the head of a numerous army. Degenerate soldiers guarded the pass where three hundred Spartan heroes had once arrested the Persian hosts, and fled as Alaric approached. Even at Thermopylae no resistance was made. The country was laid waste with fire and sword. Athens purchased her preservation at an enormous ransom. Corinth, Argos, and Sparta yielded without a blow, but did not escape the doom of vanquished cities. Their palaces were burned, their families were enslaved, and their works of art were destroyed.

Only one general remained to the desponding Arcadius,–Stilicho, trained in the armies of Theodosius, who had virtually intrusted to him, although by birth a Vandal, the guardianship of his children. We see in these latter days of the Empire that the best generals were of barbaric birth,–an impressive commentary on the degeneracy of the legions. At the approach of Stilicho, Alaric retired at first, but collecting a force of ten thousand men penetrated the Julian Alps, and advanced into Italy. The Emperor Honorius was obliged to summon to his rescue his dispirited legions from every quarter, even from the fortresses of the Rhine and the Caledonian wall, with which Stilicho compelled Alaric to retire, but only on a subsidy of two tons of gold. The Roman people, supposing that they were delivered, returned to their circuses and gladiatorial shows. Yet Italy was only temporarily delivered, for Stilicho,–the hero of Pollentia,–with the collected forces of the whole western Empire, might still have defied the armies of the Goths and staved off the ruin another generation, had not imperial jealousy and the voice of envy removed him from command. The supreme guardian of the western Empire, in the greatest crisis of its history, himself removes the last hope of Rome. The frivolous senate which Stilicho had saved, and the weak and timid emperor whom he guarded, were alike demented. Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat. In an evil hour the brave general was assassinated.

The Gothic king observing the revolutions at the palace, the elevation of incompetent generals, and the general security in which the people indulged, resolved to march to a renewed attack. Again he crossed the Alps, with a still greater army, and invaded Italy, destroying everything in his path. Without obstruction he crossed the Apennines, ravaged the fertile plains of Umbria, and reached the city, which for four hundred years had not been violated by the presence of a foreign enemy. The walls were then twenty-five miles in circuit, and contained so large a population that it affected indifference. Alaric made no attempt to take the city by storm, but quietly and patiently enclosed it with a cordon through which nothing could force its way,–as the Prussians in our day invested Paris. The city, unprovided for a siege, soon felt all the evils of famine, to which pestilence was naturally added. In despair, the haughty citizens condescended to sue for a ransom. Alaric fixed the price of his retreat at the surrender of all the gold and silver, all the precious movables, and all the slaves of barbaric birth. He afterwards somewhat modified his demands, but marched away with more spoil than the Romans brought from Carthage and Antioch.

Honorius intrenched himself at Ravenna, and refused to treat with the magnanimous Alaric. Again, consequently, he marched against the doomed capital; again invested it; again cut off supplies. In vain did the nobles organize a defence,–there were no defenders. Slaves would not fight, and a degenerate rabble could not resist a warlike and superior race. Cowardice and treachery opened the gates. In the dead of night the Gothic trumpets rang unanswered in the streets. The old heroic virtues were gone. No resistance was made. Nobody fought from temples and palaces. The queen of the world, for five days and nights, was exposed to the lust and cupidity of despised barbarians. Yet a general slaughter was not made; and as much wealth as could be collected into the churches of St. Peter and St. Paul was spared. The superstitious barbarians in some degree respected churches. But the spoils of the city were immense and incalculable,–gold, jewels, vestments, statues, vases, silver plate, precious furniture, spoils of Oriental cities,–the collective treasures of the world,–all were piled upon the Gothic wagons. The sons and daughters of patrician families became, in their turn, slaves to the barbarians. Fugitives thronged the shores of Syria and Egypt, begging daily bread. The Roman world was filled with grief and consternation. Its proud capital was sacked, since no one would defend it. “The Empire fell,” says Guizot, “because no one belonged to it.” The news of the capture “made the tongue of old Saint Jerome to cling to the roof of his mouth in his cell at Bethlehem. What is now to be seen,” cried he, “but conflagration, slaughter, ruin,–the universal shipwreck of society?” The same words of despair came from Saint Augustine at Hippo. Both had seen the city in the height of its material grandeur, and now it was laid low and desolate. The end of all things seemed to be at hand; and the only consolation of the great churchmen of the age was the belief in the second coming of our Lord.

The sack of Rome by Alaric, A.D. 410, was followed in less than half a century by a second capture and a second spoliation at the hands of the Vandals, with Genseric at their head,–a tribe of barbarians of kindred Germanic race, but fiercer instincts and more hideous peculiarities. This time, the inhabitants of Rome (for Alaric had not destroyed it,–only robbed it) put on no airs of indifference or defiance. They knew their weakness. They begged for mercy.

The last hope of the city was her Christian bishop; and the great Leo, who was to Rome what Augustine had been to Carthage when that capital also fell into the hands of Vandals, hastened to the barbarian’s camp. The only concession he could get was that the lives of the people should be spared,–a promise only partially kept. The second pillage lasted fourteen days and nights. The Vandals transferred to their ships all that the Goths had left, even to the trophies of the churches and ancient temples; the statues which ornamented the capital, the holy vessels of the Jewish temple which Titus had brought from Jerusalem, imperial sideboards of massive silver, the jewels of senatorial families, with their wives and daughters,–all were carried away to Carthage, the seat of the new Empire of the Vandals, A.D. 455, then once more a flourishing city. The haughty capital met the fate which she had inflicted on her rival in the days of Cato the censor, but fell still more ingloriously, and never would have recovered from this second fall had not her immortal bishop, rising with the greatness of the crisis, laid the foundation of a new power,–that spiritual domination which controlled the Gothic nations for more than a thousand years.

With the fall of Rome,–yet too great a city to be wholly despoiled or ruined, and which has remained even to this day the centre of what is most interesting in the world,–I should close this Lecture; but I must glance rapidly over the whole Empire, and show its condition when the imperial capital was spoiled, humiliated, and deserted.

The Suevi, Alans, and Vandals invaded Spain, and erected their barbaric monarchies. The Goths were established in the south of Gaul, while the north was occupied by the Franks and Burgundians. England, abandoned by the Romans, was invaded by the Saxons, who formed permanent conquests. In Italy there were Goths and Heruli and Lombards. All these races were Germanic. They probably made serfs or slaves of the old population, or were incorporated with them. They became the new rulers of the devastated provinces; and all became, sooner or later, converts to a nominal Christianity, the supreme guardian of which was the Pope, whose authority they all recognized. The languages which sprang up in Europe were a blending of the Roman, Celtic, and Germanic. In Spain and Italy the Latin predominated, as the Saxon prevailed in England after the Norman conquest. Of all the new settlers in the Roman world, the Normans, who made no great incursions till the time of Charlemagne, were probably the strongest and most refined. But they all alike had the same national traits, substantially; and they entered upon the possessions of the Romans after various contests, more or less successful, for two hundred and fifty years.

The Empire might have been invaded by these barbarians in the time of the Antonines, and perhaps earlier; but it would not have succumbed to them. The Legions were then severely disciplined, the central power was established, and the seeds of ruin had not then brought forth their wretched fruits. But in the fifth century nothing could have saved the Empire. Its decline had been rapid for two hundred years, until at last it became as weak as the Oriental monarchies which Alexander subdued. It fell like a decayed and rotten tree. As a political State all vitality had fled from it. The only remaining conservative forces came from Christianity; and Christianity was itself corrupted, and had become a part of the institutions of the State.

It is mournful to think that a brilliant external civilization was so feeble to arrest both decay and ruin. It is sad to think that neither art nor literature nor law had conservative strength; that the manners and habits of the people grew worse and worse, as is universally admitted, amid all the glories and triumphs and boastings of the proudest works of man. “A world as fair and as glorious as our own,” says Sismondi, “was permitted to perish.” Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Athens, met the old fate of Babylon, of Tyre, of Carthage. Degeneracy was as marked and rapid in the former, notwithstanding all the civilizing influences of letters, jurisprudence, arts, and utilitarian science, as in the latter nations,–a most significant and impressive commentary on the uniform destinies of nations, when those virtues on which the strength of man is based have passed away. An observer in the days of Theodosius would very likely have seen the churches of Rome as fully attended as are those in New York itself to-day; and he would have seen a more magnificent city,–and yet it fell. There is no cure for a corrupt and rotten civilization. As the farms of the old Puritans of Massachusetts and Connecticut are gradually but surely passing into the hands of the Irish, because the sons and grandsons of the old New-England farmer prefer the uncertainties and excitements of a demoralized city-life to laborious and honest work, so the possessions of the Romans passed into the hands of German barbarians, who were strong and healthy and religious. They desolated, but they reconstructed.

The punishment of the enervated and sensual Roman was by war. We in America do not fear this calamity, and have no present cause of fear, because we have not sunk to the weakness and wickedness of the Romans, and because we have no powerful external enemies. But if amid our magnificent triumphs of science and art, we should accept the Epicureanism of the ancients and fall into their ways of life, then there would be the same decline which marked them,–I mean in virtue and public morality,–and there would be the same penalty; not perhaps destruction from external enemies, as in Persia, Syria, Greece, and Rome, but some grievous and unexpected series of catastrophes which would be as mournful, as humiliating, as ruinous, as were the incursions of the Germanic races. The operations of law, natural and moral, are uniform. No individual and no nation can escape its penalty. The world will not be destroyed; Christianity will not prove a failure,–but new forces will arise over the old, and prevail. Great changes will come. He whose right it is to rule will overturn and overturn: but “creation shall succeed destruction; melodious birth-songs will come from the fires of the burning phoenix,” assuring us that the progress of the race is certain, even if nations are doomed to a decline and fall whenever conservative forces are not strong enough to resist the torrent of selfishness, vanity, and sin.

Authorities.

The original authorities are Ammianus Marcellinus, Zosimus, Sozomen, Socrates, orations of Gregory Nazianzen, Theodoret, the Theodosian Code, Sulpicius Severus, Life of Martin of Tours, Life of Ambrose by Paulinus, Augustine’s “De Civitate Dei,” Epistles of Ambrose; also those of Jerome; Claudien. The best modern authorities are Tillemont’s History of the Emperors; Gibbon’s Decline and Fall; Milmans’s History of Christianity; Neander; Sheppard’s Fall of Rome; and Flécier’s Life of Theodosius. There are several popular Lives of Theodosius in French, but very few in English.