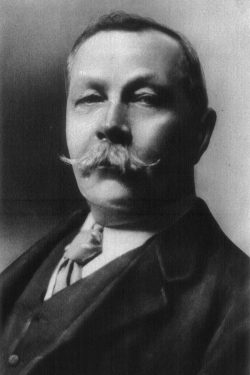

The Fate of the Evangeline by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Fate of the Evangeline

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Boy’s Own Paper, Christmas number, 1885.

The Fate of the Evangeline Contents

The Fate of the Evangeline I

The Fate of the Evangeline II

The Fate of the Evangeline III

The Fate of the Evangeline I

My wife and I often laugh when we happen to glance at some of the modern realistic sensational stories, for, however strange and exciting they may be we invariably come to the conclusion that they are tame compared to our own experiences when life was young with us.

More than once, indeed, she has asked me to write the circumstances down, but when I considered how few people there are in England who might remember the Evangeline or care to know the real history of her disappearance, it has seemed to me to be hardly worth while to revive the subject. Even here in Australia, however, we do occasionally see some reference to her in the papers or magazines, so that it is evident that there are those who have not quite forgotten the strange story: and so at this merry Christmastide I am tempted to set the matter straight.

At the time her fate excited a most intense and lively interest all over the British Islands, as was shown by the notices in the newspapers and by numerous letters which appeared upon the subject. As an example of this, as well as to give the facts in a succinct form, I shall preface this narrative by a few clippings chosen from many which we collected after the event, which are so numerous that my wife has filled a small scrapbook with them. This first one is from the “Inverness Gazette” of September 24th, 1873.

“PAINFUL OCCURRENCE IN THE HEBRIDES.—A sad accident, which it is feared has been attended with loss of life, has occurred at Ardvoe, which is a small uninhabited island lying about forty miles north-west of Harris and about half that distance south of the Flannons. It appears that a yacht named the Evangeline, belonging to Mr. Scholefield, jun., the son of the well-known banker of the firm Scholefield, Davies, and Co., had put in there, and that the passengers, with the two seamen who formed the crew, had pitched two tents upon the beach, in which they camped out for two or three days. This they did no doubt out of admiration for the rugged beauty of the spot, and perhaps from a sense of the novelty of their situation upon this lonely island. Besides Mr. Scholefield there were on the Evangeline a young lady named Miss Lucy Forrester, who is understood to be his fiancée, and her father, Colonel Forrester, of Teddington, near London. As the weather was very warm, the two gentlemen remained upon shore during the night, sleeping in one tent, while the seamen occupied the other. The young lady, however, was in the habit of rowing back to the yacht in the dinghy and sleeping in her own cabin, coming back by the same means in the morning. One day, the third of their residence upon the island, Colonel Forrester, looking out of the tent at dawn, was astonished and horrified to see that the moorings of the boat had given way, and that she was drifting rapidly out to sea. He promptly gave the alarm, and Mr. Scholefield, with one of the sailors, attempted to swim out to her, but they found that the yacht, owing to the fresh breeze and the fact that one of the sails had been so clumsily furled as to offer a considerable surface to the wind, was making such headway that it was impossible to overtake her. When last seen she was drifting along in a west-sou’-westerly direction with the unfortunate young lady on board. To make matters worse, it was three days before the party on the island were able to communicate with a passing fishing-boat and inform them of the sad occurrence. Both before and since, the weather has been so tempestuous that there is little hope of the safety of the missing yacht. We hear, however, that a reward of a thousand pounds has been offered by the firm of Scholefield to the boat which finds her and of five thousand to the one which brings Miss Forrester back in safety. Apart from any recompense, however, we are sure that the chivalry of our brave fishermen will lead them to do everything in their power to succour this young lady, who is said to possess personal charms of the highest order. Our only grain of consolation is that the Evangeline was well provided both with provisions and with water.”

This appeared upon September 24th, four days after the disappearance of the yacht. Upon the 25th the following telegram was sent from the north of Ireland:

“Portrush.—John Mullins, of this town, fisherman, reports that upon the morning of the 21st he sighted a yacht which answered to the description of the missing Evangeline. His own boat was at that time about fifty miles to the north of Malin Head, and was hove-to, the weather being very thick and dirty. The yacht passed within two hundred yards of his starboard quarter, but the fog was so great that he could not swear to her appearance. She was running in a westerly direction under a reefed mainsail and jib. There was a man at the tiller. He distinctly saw a woman on board, and thinks that she called out to him, but could not be sure owing to the howling of the wind.”

I have many other extracts here expressive of the doubts and fears which existed as to the fate of the Evangeline, but I shall not quote one more than is necessary. Here is the Central News telegram which quashed the last lingering hopes of the most sanguine. It went the round of the papers upon the 3rd of October.

“Galway, October 2nd, 7.25 p.m.—The fishing boat Glenmullet has just come in, towing behind her a mass of wreckage, which leaves no doubt as to the fate of the unfortunate Evangeline and of the young lady who was on board of her. The fragments brought in consist of the bowsprit, figurehead, and part of the bows, with the name engraved upon it. From its appearance it is conjectured that the yacht was blown on to one of the dangerous reefs upon the north-west coast, and that after being broken up there this and possibly other fragments had drifted out to sea. Attached to it is a fragment of the fatal rope, the snapping of which was the original cause of the disaster. It is a stout cable of manilla hemp, and the fracture is a clean one—so clean as to suggest friction against a very sharp rock or the cut of a knife. Several boats have gone up and down the coast this evening in the hope of finding some more débris or of ascertaining with certainty the fate of the young lady.”

From that day to this, however, nothing fresh has been learned of the fate of the Evangeline or of Miss Lucy Forrester, who was on board of her. These three extracts represent all that has ever been learned about either of them, and in these even there are several statements which the press at the time showed to be incredible. For example, how could the fisherman John Mullins say that he saw a man on board when Ardvoe is an uninhabited island, and therefore no one could possibly have got on board except Miss Forrester? It was clear that he was either mistaken in the boat or else that he imagined the man. Again, it was pointed out in a leader in the “Scotsman” that the conjecture that the rope was either cut by a rock or by a knife was manifestly absurd, since there are no rocks around Ardvoe, but a uniform sandy bottom, and it would be preposterous to suppose that Miss Forrester, who was a lady as remarkable for her firmness of mind as for her beauty, would deliberately sever the rope which attached her to her father, her lover, and to life itself. “It would be well,” the “Scotsman” concluded, “if those who express opinions upon such subjects would bear in mind those simple rules as to the analysis of evidence laid down by Auguste Dupin. ‘Exclude the impossible,’ he remarks in one of Poe’s immortal stories, ‘and what is left, however improbable, must be the truth.’ Now, since it is impossible that a rock divided the rope, and impossible that the young lady divided it, and doubly impossible that anybody else divided it, it follows that it parted of its own accord, either owing to some flaw in its texture or from some previous injury that it may have sustained. Thus this sad occurrence, about which conjecture is so rife, sinks at once into the category of common accidents, which, however deplorable, can neither be foreseen nor prevented.”

There was one other theory which I shall just allude to before I commence my own personal narrative. That is the suggestion that either of the two sailors had had a spite against Mr. Scholefield or Colonel Forrester and had severed the rope out of revenge. That, however, is quite out of the question, for they were both men of good character and old servants of the Scholefields. My wife tells me that it is mere laziness which makes me sit with the scrapbook before me copying out all these old newspaper articles and conjectures. It is certainly the easiest way to tell my story, but I must now put them severely aside and tell you in my own words as concisely as I can what the real facts were.

* * *

My name is John Vincent Gibbs, and I am the son of Nathaniel Gibbs, formerly a captain in one of the West Indian regiments. My father was a very handsome man, and he succeeded in winning the heart of a Miss Leblanche, who was heiress to a good sugar plantation in Demerara. By this marriage my father became fairly rich, and, having left the army, he settled down to the life of a planter. I was born within a year of the marriage, but my mother never rose again from her bed, and my father was so broken-hearted at his loss that he pined away and followed her to the grave within a few months.

I have thus never known either of my two parents, and the loss of their control, combined perhaps with my tropical birthplace, made me, I fear, somewhat headstrong and impetuous.

Immediately that I became old enough to be my own master I sold the estate and invested the money in Government stock in such a way as to insure me an income of fifteen hundred a year for life. I then came to Europe, and for a long time led a strange Bohemian life, flitting from one University to another, and studying spasmodically those subjects which interested me. I went to Heidelberg for a year in order to read chemistry and metaphysics, and when I returned to London I plunged for the first time into society. I was then twenty-four years of age, dark-haired, dark-eyed, swarthy, with a smattering of all knowledge and a mastery of none.

It was during this season in London that I first saw Lucy Forrester. How can I describe her so as to give even the faintest conception of her beauty? To my eyes no woman ever had been or could be so fair. Her face, her voice, her figure, every movement and action, were part of one rare and harmonious whole. Suffice it that I loved her the very evening that I saw her, and that I went on day after day increasing and nourishing this love until it possessed my whole being.

At first my suit prospered well. I made the acquaintance of her father, an elderly soldier, and became a frequent visitor at the house. I soon saw that the keynote of Miss Forrester’s character was her intense devotion to her father, and accordingly I strove to win her regard by showing extreme deference and attention to him. I succeeded in interesting her in many topics, too, and we became very friendly. At last I ventured to speak to her of love, and told her of the passion which consumed me. I suppose I spoke wildly and fiercely, for she was frightened and shrank from me.

I renewed the subject another day, however, with better success. She confessed to me then that she loved me, but added firmly that she was her father’s only child, and that it was her duty to devote her life to comforting his declining years. Her personal feelings, she said, should never prevent her from performing that duty. It mattered not. The confession that I was dear to her filled me with ecstasy. For the rest I was content to wait.

During this time the colonel had favoured my suit. I have no doubt that some gossip had exaggerated my wealth and given him false ideas of my importance. One day in conversation I told him what my resources were. I saw his face change as he listened to me, and from that moment his demeanour altered.

It chanced that about the same time young Scholefield, the son of the rich banker, came back from Oxford, and having met Lucy, became very marked in his attentions to her. Colonel Forrester at once encouraged his addresses in every possible way, and I received a curt note from him informing me that I should do well to discontinue my visits.

I still had hopes that Lucy would not be influenced by her father’s mercenary schemes. For days I frequented her usual haunts, seeking an opportunity of speaking to her. At last I met her alone one morning in St. James’s Park. She looked me straight in the face, and there was an expression of great tenderness and sadness in her eyes, but she would have passed me without speaking. All the blood seemed to rush into my head, and I caught her by the wrist to detain her.

“You have given me up, then?” I cried. “There is no longer any hope for me.”

“Hush, Jack!” she said, for I had raised my voice excitedly. “I warned you how it would be. It is my father’s wish and I must obey him, whatever it costs. Let me go now. You must not hold me any more.”

“And there is no hope?”

“You will soon forget me,” she said. “You must not think of me again.”

“Ah, you are as bad as he,” I cried, excitedly. “I read it in your eyes. It is the money—the wretched money.” I was sorry for the words the moment after I had said them, but she had passed gravely on, and I was alone.

I sat down upon one of the benches in the park, and rested my head upon my hands. I felt numbed and stupefied. The world and everything in it had changed for me during the last ten minutes. People passed me as I sat—people who laughed and joked and gossiped. It seemed to me that I watched them almost as a dead man might watch the living. I had no sympathy with their little aims, their little pleasures and their little pains. “I’ll get away from the whole drove of them,” I said, as I rose from my seat. “The women are false and the men are fools, and everything is mean and sordid.” My first love had unhappily converted me to cynicism, rash and foolish as I was, as it has many such a man before.

For many months I travelled, endeavouring by fresh scenes and new experiences to drive away the memory of that fair false face. At Venice I heard that she was engaged to be married to young Scholefield. “He’s got a lot of money,” this tourist said—it was at the table d’hôte at the Hotel de l’Europe. “It’s a splendid match for her.” For her!

When I came back to England I flitted restlessly about from one place to another, avoiding the haunts of my old associates, and leading a lonely and gloomy life. It was about this time that the idea first occurred to me of separating my person from mankind as widely as my thoughts and feelings were distinct from theirs. My temperament was, I think, naturally a somewhat morbid one, and my disappointment had made me a complete misanthrope. To me, without parents, friends, or relations, Lucy had been everything, and now that she was gone the very sight of a human face was hateful to me. Loneliness in a wilderness, I reflected, was less irksome than loneliness in a city. In some wild spot I might be face to face with nature and pursue the studies into which I had plunged once more, without interruption or disturbance.

As this resolution began to grow upon me I thought of this island of Ardvoe, which, curiously enough, had been first mentioned to me by Scholefield on one of the few occasions when we had been together in the house of the Forresters. I had heard him speak of its lonely and desolate position, and of its beauty, for his father had estates in Skye, from which he was wont to make yachting trips in summer, and in one of these he had visited the island. It frequently happened, he said, that no one set foot upon it during the whole year, for there was no grass for sheep, and nothing to attract fishermen. This, I thought, would be the very place for me.

Full of my new idea, I travelled to Skye, and from thence to Uist. There I hired a fishing-boat from a man named McDiarmid, and sailed with him and his son to the island. It was just such a place as I had imagined—rugged and desolate, with high, dark crags rising up from a girdle of sand. It had been once, McDiarmid said, a famous emporium for the goods of smugglers, which used to be stored there, and then conveyed over to the Scotch coast as occasion served. He showed me several of the caves of these gentry, and one in particular, which I immediately determined should be my own future dwelling. It was approached by a labyrinth of rocky paths, which effectually secured it against any intruder, while it was roomy inside, and lit up by an aperture in the rock above, which might be covered over in wet weather.

The fisherman told me that his father had pointed the spot out to him, but that it was not commonly known to the rare visitors who came to the island. There was abundance of fresh water, and fish were to be caught in any quantity.

I was so well satisfied with my survey that I returned to Scotland with the full intention of realising my wild misanthropical scheme.

In Glasgow I purchased most of the more important things that I wanted to take with me. These included a sleeping bag, such as is used in the Arctic seas; several mathematical and astronomical instruments; a very varied and extensive assortment of books, including nearly every modern work upon chemistry and physics; a double-barrelled fowling-piece, fishing-tackle, lamps, candles, and oil. Subsequently at Oban and Stornoway I purchased two bags of potatoes, a sack of flour, and a quantity of tinned meats, together with a small stove. All these things I conveyed over in McDiarmid’s boat, having already bound both himself and his son to secrecy upon the matter—a promise which, as far as I know, neither of them ever broke. I also had a table and chair conveyed across, with a plentiful supply of pens, ink, and paper.

All these things were stowed away in the cave, and I then requested McDiarmid to call upon the first of each month, or as soon after as the weather permitted, in case I needed anything. This he promised to do, and having been well paid for his services, he departed, leaving me upon the island.

It was a strange sensation to me when I saw the brown sail of his boat sinking below the horizon, until at last it disappeared, and left one broad, unbroken sheet of water before me. That boat was the last tie which bound me to the human race. When it had vanished, and I returned into my cave with the knowledge that no sight or sound could jar upon me now, I felt the first approach to satisfaction which I had had through all those weary months. A fire was sparkling in the stove, for fuel was plentiful on the island, and the long stove-pipe had been so arranged that it projected through the aperture above, and so carried the smoke away. I boiled some potatoes and made a hearty meal, after which I wrote and read until nightfall, when I crept into my bag and slept soundly.

It might weary my readers should I speak of my existence upon this island, though the petty details of my housekeeping seem to interest my dear wife more than anything else, and ten years have not quite exhausted her questions upon the subject. I cannot say that I was happy, but I was less unhappy than I could have believed it possible. At times, it is true, I was plunged into the deepest melancholy, and would remain so for days, without energy enough to light my fire or to cook my food. On these occasions I would wander aimlessly among the hills and along the shore until I was worn out with fatigue. After these attacks, however, I would become, if not placid, at least torpid for a time. Occasionally I could even smile at my strange life as an anchorite, and speculate as to whether the lord of the manor, since I presumed the island belonged to some one, would become aware of my existence, and if so, whether he would evict me ignominiously, or claim a rent for my little cavern.