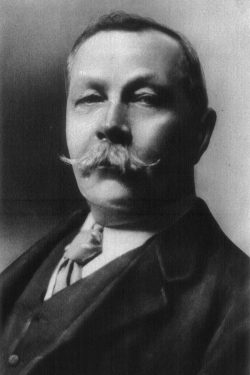

Uncle Jeremy’s Household by Arthur Conan Doyle

Uncle Jeremy’s Household

by

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Published in Boy’s Own Paper, 8 January—19 February 1887.

Uncle Jeremy’s Household Contents

Uncle Jeremy’s Household I

Uncle Jeremy’s Household II

Uncle Jeremy’s Household III

Uncle Jeremy’s Household IV

Uncle Jeremy’s Household V

Uncle Jeremy’s Household VI

Uncle Jeremy’s Household I

My life has been a somewhat chequered one, and it has fallen to my lot during the course of it to have had several unusual experiences. There is one episode, however, which is so surpassingly strange that whenever I look back to it it reduces the others to insignificance. It looks up out of the mists of the past, gloomy and fantastic, overshadowing the eventless years which preceded and which followed it.

It is not a story which I have often told. A few, but only a few, who know me well have heard the facts from my lips. I have been asked from time to time by these to narrate them to some assemblage of friends, but I have invariably refused, for I have no desire to gain a reputation as an amateur Munchausen. I have yielded to their wishes, however, so far as to draw up this written statement of the facts in connection with my visit to Dunkelthwaite.

Here is John Thurston’s first letter to me. It is dated April 1862. I take it from my desk and copy it as it stands:

“My dear Lawrence,—if you knew my utter loneliness and complete ennui I am sure you would have pity upon me and come up to share my solitude. You have often made vague promises of visiting Dunkelthwaite and having a look at the Yorkshire Fells. What time could suit you better than the present? Of course I understand that you are hard at work, but as you are not actually taking out classes you can read just as well here as in Baker Street. Pack up your books, like a good fellow, and come along! We have a snug little room, with writing-desk and armchair, which will just do for your study. Let me know when we may expect you.

“When I say that I am lonely I do not mean that there is any lack of people in the house. On the contrary, we form rather a large household. First and foremost, of course, comes my poor Uncle Jeremy, garrulous and imbecile, shuffling about in his list slippers, and composing, as is his wont, innumerable bad verses. I think I told you when last we met of that trait in his character. It has attained such a pitch that he has an amanuensis, whose sole duty it is to copy down and preserve these effusions. This fellow, whose name is Copperthorne, has become as necessary to the old man as his foolscap or as the ‘Universal Rhyming Dictionary.’ I can’t say I care for him myself, but then I have always shared Caesar’s prejudice against lean men—though, by the way, little Julius was rather inclined that way himself if we may believe the medals. Then we have the two children of my Uncle Samuel, who were adopted by Jeremy—there were three of them, but one has gone the way of all flesh—and their governess, a stylish-looking brunette with Indian blood in her veins. Besides all these, there are three maidservants and/the old groom, so you see we have quite a little world of our own in this out-of-the-way corner. For all that, my dear Hugh, I long for a familiar face and for a congenial companion. I am deep in chemistry myself, so I won’t interrupt your studies. Write by return to your isolated friend,

“JOHN H. THURSTON.”

At the time that I received this letter I was in lodgings in London, and was working hard for the final examination which should make me a qualified medical man. Thurston and I had been close friends at Cambridge before I took to the study of medicine, and I had a great desire to see him again. On the other hand, I was rather afraid that, in spite of his assurances, my studies might suffer by the change. I pictured to myself the childish old man, the lean secretary, the stylish governess, the two children, probably spoiled and noisy, and I came to the conclusion that when we were all cooped together in one country house there would be very little room for quiet reading. At the end of two days’ cogitation I had almost made up my mind to refuse the invitation, when I received another letter from Yorkshire even more pressing than the first.

“We expect to hear from you by every post,” my friend said, “and there is never a knock that I do not think it is a telegram announcing your train. Your room is all ready, and I think you will find it comfortable. Uncle Jeremy bids me say how very happy he will be to see you. He would have written, but he is absorbed in a great epic poem of five thousand lines or so, and he spends his day trotting about the rooms, while Copperthorne stalks behind him like the monster in Frankenstein, with notebook and pencil, jotting down the words of wisdom as they drop from his lips. By the way, I think I mentioned the brunettish governess to you. I might throw her out as a bait to you if you retain your taste for ethnological studies. She is the child of an Indian chieftain, whose wife was an Englishwoman. He was killed in the mutiny, fighting against us, and, his estates being seized by Government, his daughter, then fifteen, was left almost destitute. Some charitable German merchant in Calcutta adopted her, it seems, and brought her over to Europe with him together with his own daughter. The latter died, and then Miss Warrender—as we call her, after her mother—answered uncle’s advertisement; and here she is. Now, my dear boy, stand not upon the order of your coming, but come at once.”

There were other things in this second letter which prevent me from quoting it in full.

There was no resisting the importunity of my old friend, so, with many inward grumbles, I hastily packed up my books, and, having telegraphed overnight, started for Yorkshire the first thing in the morning. I well remember that it was a miserable day, and that the journey seemed to be an interminable one as I sat huddled up in a corner of the draughty carriage, revolving in my mind many problems of surgery and of medicine. I had been warned that the little wayside station of Ingleton, some fifteen miles from Carnforth, was the nearest to my destination, and there I alighted just as John Thurston came dashing down the country road in a high dog-cart. He waved his whip enthusiastically at the sight of me, and pulling up his horse with a jerk, sprang out and on to the platform.

“My dear Hugh,” he cried, “I’m so delighted to see you! It’s so kind of you to come!” He wrung my hand until my arm ached.

“I’m afraid you’ll find me very bad company now that I am here,” I answered; “I am up to my eyes in work.”

“Of course, of course,” he said, in his good-humoured way. “I reckoned on this. We’ll have time for a crack at the rabbits for all that. It’s a longish drive, and you must be bitterly cold, so let’s start for home at once.”

We rattled off along the dusty road.

“I think you’ll like your room,” my friend remarked. “You’ll soon find yourself at home. You know it is not often that I visit Dunkelthwaite myself, and I am only just beginning to settle down and get my laboratory into working order. I have been here a fortnight. It’s an open secret that I occupy a prominent position in old Uncle Jeremy’s will, so my father thought it only right that I should come up and do the polite. Under the circumstances I can hardly do less than put myself out a little now and again.”

“Certainly not,” I said.

“And besides, he’s a very good old fellow. You’ll be amused at our ménage. A princess for governess—it sounds well, doesn’t it? I think our imperturbable secretary is somewhat gone in that direction. Turn up your coat-collar, for the wind is very sharp.”

The road ran over a succession of low bleak hills, which were devoid of all vegetation save a few scattered gorse-bushes and a thin covering of stiff wiry grass, which gave nourishment to a scattered flock of lean, hungry-looking sheep. Alternately we dipped down into a hollow or rose to the summit of an eminence from which we could see the road winding as a thin white track over successive hills beyond. Every here and there the monotony of the landscape was broken by jagged scarps, where the grey granite peeped grimly out, as though nature had been sorely wounded until her gaunt bones protruded through their covering. In the distance lay a range of mountains, with one great peak shooting up from amongst them coquettishly draped in a wreath of clouds which reflected the ruddy light of the setting sun.

“That’s Ingleborough,” my companion said, indicating the mountain with his whip, “and these are the Yorkshire Fells. You won’t find a wilder, bleaker place in all England. They breed a good race of men. The raw militia who beat the Scotch chivalry at the Battle of the Standard came from this part of the country. Just jump down, old fellow and open the gate.”

We had pulled up at a place where a long moss-grown wall ran parallel to the road. It was broken by a dilapidated iron gate, flanked by two pillars, on the summit of which were stone devices which appeared to represent some heraldic animal, though wind and rain had reduced them to shapeless blocks. A ruined cottage, which may have served at some time as a lodge, stood on one side. I pushed the gate open and we drove up a long, winding avenue, grass-grown and uneven, but lined by magnificent oaks, which shot their branches so thickly over us that the evening twilight deepened suddenly into darkness.

“I’m afraid our avenue won’t impress you much,” Thurston said, with a laugh. “It’s one of the old man’s whims to let nature have her way in everything. Here we are at last at Dunkelthwaite.”

As he spoke we swung round a curve in the avenue marked by a patriarchal oak which towered high above the others, and came upon a great square whitewashed house with a lawn in front of it. The lower part of the building was all in shadow, but up at the top a row of blood-shot windows glimmered out at the setting sun. At the sound of the wheels an old man in livery ran out and seized the horse’s head when we pulled up.

“You can put her up, Elijah,” my friend said, as we jumped down. “Hugh, let me introduce you to my Uncle Jeremy.”

“How d’ye do? How d’ye do?” cried a wheezy cracked voice, and looking up I saw a little red-faced man who was standing waiting for us in the porch. He wore a cotton cloth tied round his head after the fashion of Pope and other eighteenth-century celebrities, and was further distinguished by a pair of enormous slippers. These contrasted so strangely with his thin spindle shanks that he appeared to be wearing snowshoes, a resemblance which was heightened by the fact that when he walked he was compelled to slide his feet along the ground in order to retain his grip of these unwieldly appendages.

“You must be tired, sir. Yes, and cold, sir,” he said, in a strange jerky way, as he shook me by the hand. “We must be hospitable to you, we must indeed. Hospitality is one of the old-world virtues which we still retain. Let me see, what are those lines? ‘Ready and strong the Yorkshire arm, but oh, the Yorkshire heart is warm?’ Neat and terse, sir. That comes from one of my poems. What poem is it, Copperthorne?”

“‘The Harrying of Borrodaile’,” said a voice behind him, and a tall long-visaged man stepped forward into the circle of light which was thrown by the lamp above the porch. John introduced us, and I remember that his hand as I shook it was cold and unpleasantly clammy.

This ceremony over, my friend led the way to my room, passing through many passages and corridors connected by old-fashioned and irregular staircases. I noticed as I passed the thickness of the walls and the strange slants and angles of the ceilings, suggestive of mysterious spaces above. The chamber set apart for me proved, as John had said, to be a cheery little sanctum with a crackling fire and a well-stocked bookcase. I began to think as I pulled on my slippers that I might have done worse after all than accept this Yorkshire invitation.