THE SAILOR BOY POEM by Adelaide Anne Procter

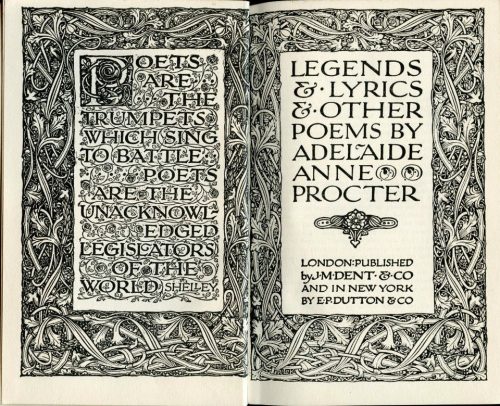

Poetry from Legends and Lyrics First Series.

ADELAIDE ANNE PROCTER VERSE: THE SAILOR BOY POEM

My Life you ask of? why, you know

Full soon my little Life is told;

It has had no great joy or woe,

For I am only twelve years old.

Ere long I hope I shall have been

On my first voyage, and wonders seen.

Some princess I may help to free

From pirates, on a far-off sea;

Or, on some desert isle be left,

Of friends and shipmates all bereft.

For the first time I venture forth,

From our blue mountains of the north.

My kinsman kept the lodge that stood

Guarding the entrance near the wood,

By the stone gateway grey and old,

With quaint devices carved about,

And broken shields; while dragons bold

Glared on the common world without;

And the long trembling ivy spray

Half hid the centuries’ decay.

In solitude and silence grand

The castle towered above the land:

The castle of the Earl, whose name

(Wrapped in old bloody legends) came

Down through the times when Truth and Right

Bent down to armèd Pride and Might.

He owned the country far and near;

And, for some weeks in every year,

(When the brown leaves were falling fast

And the long, lingering autumn passed,)

He would come down to hunt the deer,

With hound and horse in splendid pride.

The story lasts the live-long year,

The peasant’s winter evening fills,

When he is gone and they abide

In the lone quiet of their hills.

I longed, too, for the happy night,

When, all with torches flaring bright,

The crowding villagers would stand,

A patient, eager, waiting band,

Until the signal ran like flame—

“They come!” and, slackening speed, they came.

Outriders first, in pomp and state,

Pranced on their horses through the gate;

Then the four steeds as black as night,

All decked with trappings blue and white,

Drew through the crowd that opened wide,

The Earl and Countess side by side.

The stern grave Earl, with formal smile

And glistening eyes and stately pride,

Could ne’er my childish gaze beguile

From the fair presence by his side.

The lady’s soft sad glance, her eyes,

(Like stars that shone in summer skies,)

Her pure white face so calmly bent,

With gentle greetings round her sent

Her look, that always seemed to gaze

Where the blue past had closed again

Over some happy shipwrecked days,

With all their freight of love and pain:

She did not even seem to see

The little lord upon her knee.

And yet he was like angel fair,

With rosy cheeks and golden hair,

That fell on shoulders white as snow:

But the blue eyes that shone below

His clustering rings of auburn curls,

Were not his mother’s, but the Earl’s.

I feared the Earl, so cold and grim,

I never dared be seen by him.

When through our gate he used to ride,

My kinsman Walter bade me hide;

He said he was so stern.

So, when the hunt came past our way,

I always hastened to obey,

Until I heard the bugles play

The notes of their return.

But she—my very heart-strings stir

Whene’er I speak or think of her—

The whole wide world could never see

A noble lady such as she,

So full of angel charity.

Strange things of her our neighbours told

In the long winter evenings cold,

Around the fire. They would draw near

And speak half-whispering, as in fear;

As if they thought the Earl could hear

Their treason ‘gainst his name.

They thought the story that his pride

Had stooped to wed a low-born bride,

A stain upon his fame.

Some said ’twas false; there could not be

Such blot on his nobility:

But others vowed that they had heard

The actual story word for word,

From one who well my lady knew,

And had declared the story true.

In a far village, little known,

She dwelt—so ran the tale—alone.

A widowed bride, yet, oh! so bright,

Shone through the mist of grief, her charms;

They said it was the loveliest sight—

She with her baby in her arms.

The Earl, one summer morning, rode

By the sea-shore where she abode;

Again he came—that vision sweet

Drew him reluctant to her feet.

Fierce must the struggle in his heart

Have been, between his love and pride,

Until he chose that wondrous part,

To ask her to become his bride.

Yet, ere his noble name she bore,

He made her vow that nevermore

She would behold her child again,

But hide his name and hers from men.

The trembling promise duly spoken,

All links of the low past were broken;

And she arose to take her stand

Amid the nobles of the land.

Then all would wonder—could it be

That one so lowly born as she,

Raised to such height of bliss, should seem

Still living in some weary dream?

‘Tis true she bore with calmest grace

The honours of her lofty place,

Yet never smiled, in peace or joy,

Not even to greet her princely boy.

She heard, with face of white despair,

The cannon thunder through the air,

That she had given the Earl an heir.

Nay, even more, (they whispered low,

As if they scarce durst fancy so,)

That, through her lofty wedded life,

No word, no tone, betrayed the wife.

Her look seemed ever in the past;

Never to him it grew more sweet;

The self-same weary glance she cast

Upon the grey-hound at her feet,

As upon him, who bade her claim

The crowning honour of his name.

This gossip, if old Walter heard,

He checked it with a scornful word:

I never durst such tales repeat;

He was too serious and discreet

To speak of what his lord might do;

Besides, he loved my lady too.

And many a time, I recollect,

They were together in the wood;

He, with an air of grave respect,

And earnest look, uncovered stood.

And though their speech I never heard,

(Save now and then a louder word,)

I saw he spake as none but one

She loved and trusted, durst have done;

For oft I watched them in the shade

That the close forest branches made,

Till slanting golden sunbeams came

And smote the fir-trees into flame,

A radiant glory round her lit,

Then down her white robes seemed to flit,

Gilding the brown leaves on the ground,

And all the waving ferns around.

While by some gloomy pine she leant

And he in earnest talk would stand,

I saw the tear-drops, as she bent,

Fall on the flowers in her hand.—

Strange as it seemed and seems to be,

That one so sad, so cold as she,

Could love a little child like me—

Yet so it was. I never heard

Such tender words as she would say,

And murmurs, sweeter than a word,

Would breathe upon me as I lay.

While I, in smiling joy, would rest,

For hours, my head upon her breast.

Our neighbours said that none could see

In me the common childish charms,

(So grave and still I used to be,)

And yet she held me in her arms,

In a fond clasp, so close, so tight—

I often dream of it at night.

She bade me tell her all—no other

My childish thoughts e’er cared to know:

For I—I never knew my mother;

I was an orphan long ago.

And I could all my fancies pour,

That gentle loving face before.

She liked to hear me tell her all;

How that day I had climbed the tree,

To make the largest fir-cones fall;

And how one day I hoped to be

A sailor on the deep blue sea—

She loved to hear it all!

Then wondrous things she used to tell,

Of the strange dreams that she had known.

I used to love to hear them well,

If only for her sweet low tone,

Sometimes so sad, although I knew

That such things never could be true.

One day she told me such a tale

It made me grow all cold and pale,

The fearful thing she told!

Of a poor woman mad and wild

Who coined the life-blood of her child,

And tempted by a fiend, had sold

The heart out of her breast for gold.

But, when she saw me frightened seem,

She smiled, and said it was a dream.

When I look back and think of her,

My very heart-strings seem to stir;

How kind, how fair she was, how good

I cannot tell you. If I could

You, too, would love her. The mere thought

Of her great love for me has brought

Tears in my eyes: though far away,

It seems as it were yesterday.

And just as when I look on high

Through the blue silence of the sky,

Fresh stars shine out, and more and more,

Where I could see so few before;

So, the more steadily I gaze

Upon those far-off misty days,

Fresh words, fresh tones, fresh memories start

Before my eyes and in my heart.

I can remember how one day

(Talking in silly childish way)

I said how happy I should be

If I were like her son—as fair,

With just such bright blue eyes as he,

And such long locks of golden hair.

A strange smile on her pale face broke,

And in strange solemn words she spoke:

“My own, my darling one—no, no!

I love you, far, far better so.

I would not change the look you bear,

Or one wave of your dark brown hair.

The mere glance of your sunny eyes,

Deep in my deepest soul I prize

Above that baby fair!

Not one of all the Earl’s proud line

In beauty ever matched with thine;

And, ’tis by thy dark locks thou art

Bound even faster round my heart,

And made more wholly mine!”

And then she paused, and weeping said,

“You are like one who now is dead—

Who sleeps in a far-distant grave.

Oh may God grant that you may be

As noble and as good as he,

As gentle and as brave!”

Then in my childish way I cried,

“The one you tell me of who died,

Was he as noble as the Earl?”

I see her red lips scornful curl,

I feel her hold my hand again

So tightly, that I shrink in pain—

I seem to hear her say,

“He whom I tell you of, who died,

He was so noble and so gay,

So generous and so brave,

That the proud Earl by his dear side

Would look a craven slave.”

She paused; then, with a quivering sigh,

She laid her hand upon my brow:

“Live like him, darling, and so die.

Remember that he tells you now,

True peace, real honour, and content,

In cheerful pious toil abide;

That gold and splendour are but sent

To curse our vanity and pride.”

One day some childish fever pain

Burnt in my veins and fired my brain.

Moaning, I turned from side to side;

And, sobbing in my bed, I cried,

Till night in calm and darkness crept

Around me, and at last I slept.

When suddenly I woke to see

The Lady bending over me.

The drops of cold November rain

Were falling from her long, damp hair;

Her anxious eyes were dim with pain;

Yet she looked wondrous fair.

Arrayed for some great feast she came,

With stones that shone and burnt like flame;

Wound round her neck, like some bright snake,

And set like stars within her hair,

They sparkled so, they seemed to make

A glory everywhere.

I felt her tears upon my face,

Her kisses on my eyes;

And a strange thought I could not trace

I felt within my heart arise;

And, half in feverish pain, I said:

“Oh if my mother were not dead!”

And Walter bade me sleep; but she

Said, “Is it not the same to thee

That I watch by thy bed?”

I answered her, “I love you, too;

But it can never be the same;

She was no Countess like to you,

Nor wore such sparkling stones of flame.”

Oh the wild look of fear and dread!

The cry she gave of bitter woe!

I often wonder what I said

To make her moan and shudder so.

Through the long night she tended me

With such sweet care and charity.

But should weary you to tell

All that I know and love so well:

Yet one night more stands out alone

With a sad sweetness all its own.

The wind blew loud that dreary night:

Its wailing voice I well remember:

The stars shone out so large and bright

Upon the frosty fir-boughs white,

That dreary night of cold December.

I saw old Walter silent stand,

Watching the soft white flakes of snow

With looks I could not understand,

Of strange perplexity and woe.

At last he turned and took my hand,

And said the Countess just had sent

To bid us come; for she would fain

See me once more, before she went

Away—never to come again.

We came in silence through the wood

(Our footfall was the only sound)

To where the great white castle stood,

With darkness shadowing it around.

Breathless, we trod with cautious care

Up the great echoing marble stair;

Trembling, by Walter’s hand I held,

Scared by the splendours I beheld:

Now thinking, “Should the Earl appear!”

Now looking up with giddy fear

To the dim vaulted roof, that spread

Its gloomy arches overhead.

Long corridors we softly past,

(My heart was beating loud and fast)

And reached the Lady’s room at last:

A strange faint odour seemed to weigh

Upon the dim and darkened air;

One shaded lamp, with softened ray,

Scarce showed the gloomy splendour there.

The dull red brands were burning low,

And yet a fitful gleam of light,

Would now and then, with sudden glow,

Start forth, then sink again in night.

I gazed around, yet half in fear,

Till Walter told me to draw near:

And in the strange and flickering light,

Towards the Lady’s bed I crept;

All folded round with snowy white,

She lay; (one would have said she slept;)

So still the look of that white face,

It seemed as it were carved in stone,

I paused before I dared to place

Within her cold white hand my own.

But, with a smile of sweet surprise,

She turned to me her dreamy eyes;

And slowly, as if life were pain,

She drew me in her arms to lie:

She strove to speak, and strove in vain;

Each breath was like a long-drawn sigh.

The throbs that seemed to shake her breast,

The trembling clasp, so loose and weak,

At last grew calmer, and at rest;

And then she strove once more to speak:

“My God, I thank thee, that my pain

Of day by day and year by year,

Has not been suffered all in vain,

And I may die while he is near.

I will not fear but that Thy grace

Has swept away my sin and woe,

And sent this little angel face,

In my last hour to tell me so.”

(And here her voice grew faint and low,)

“My child, where’er thy life may go,

To know that thou art brave and true,

Will pierce the highest heavens through,

And even there my soul shall be

More joyful for this thought of thee.”

She folded her white hands, and stayed;

All cold and silently she lay:

I knelt beside the bed, and prayed

The prayer she used to make me say.

I said it many times, and then

She did not move, but seemed to be

In a deep sleep, nor stirred again.

No sound woke in the silent room,

Or broke the dim and solemn gloom,

Save when the brands that burnt so low,

With noisy fitful gleam of light,

Would spread around a sudden glow,

Then sink in silence and in night.

How long I stood I do not know:

At last poor Walter came, and said

(So sadly) that we now must go,

And whispered, she we loved was dead.

He bade me kiss her face once more,

Then led me sobbing to the door.

I scarcely knew what dying meant,

Yet a strange grief, before unknown,

Weighed on my spirit as we went

And left her lying all alone.

We went to the far North once more,

To seek the well-remembered home,

Where my poor kinsman dwelt before,

Whence now he was too old to roam;

And there six happy years we past,

Happy and peaceful till the last;

When poor old Walter died, and he

Blessed me and said I now might be

A sailor on the deep blue sea.

And so I go; and yet in spite

Of all the joys I long to know,

Though I look onward with delight,

With something of regret I go;

And young or old, on land or sea,

One guiding memory I shall take—

Of what She prayed that I might be,

And what I will be for her sake!