Abraham Lincoln : Civil War and Preservation of the Union – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders by John Lord

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders

Andrew Jackson : Personal Politics

Henry Clay : Compromise Legislation

Daniel Webster : The American Union

John C. Calhoun : The Slavery Question

Abraham Lincoln : Civil War and Preservation of the Union

Robert E. Lee : The Southern Confederacy

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Lincoln’s parentage

Rail splitter; country merchant

In the Black Hawk war

Postmaster

His aspirations and passion for politics

Stump speaker

Surveyor

Elected to the legislature

Lincoln as politician

Admitted to the bar

Elected member of Congress

His marriage

Lincoln as lawyer

Orator

On the slavery question

Anti-slavery agitation

The compromise of 1850

Stephen A. Douglas

Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

Charles Sumner

Dred Scott decision

Lincoln’s antagonism to Douglas

His commitment to anti-slavery cause

Rise of the Republican party

Lincoln’s debates with Douglas

Speaks in New York

Lincoln as statesman

Nomination for the presidency

His election

Inauguration

Lincoln’s cabinet; Jefferson Davis

Fort Sumter

War

Lincoln as president

Bull Run

Concentration of troops in Washington

General McClellan

His dilatory measures

Gloomy times

Retirement of McClellan

General Pope

McClellan restored, fights the battle of Antietam

Inaction and final retirement of McClellan

Burnside and the battle of Fredericksburg

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation

General Hooker

Lee’s raid in Pennsylvania

General Meade and the battle of Gettysburg

Lincoln overworked

Siege of Vicksburg

General Grant

Battle of Chattanooga

Grant made general-in-chief

March of Grant on Richmond

Military sacrifices

Siege of Petersburg

Surrender of Lee

Results of the war

Strained relations between Chase and Lincoln

Chase chief-justice

Lincoln’s second inaugural

His profound wisdom

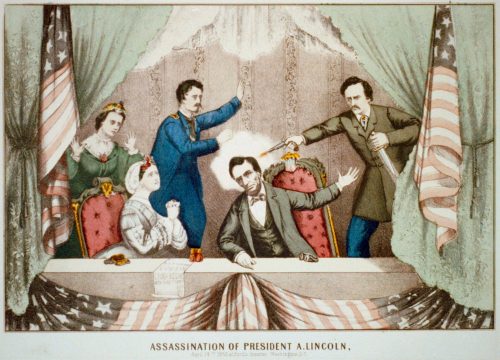

His assassination

Great services

Position in history

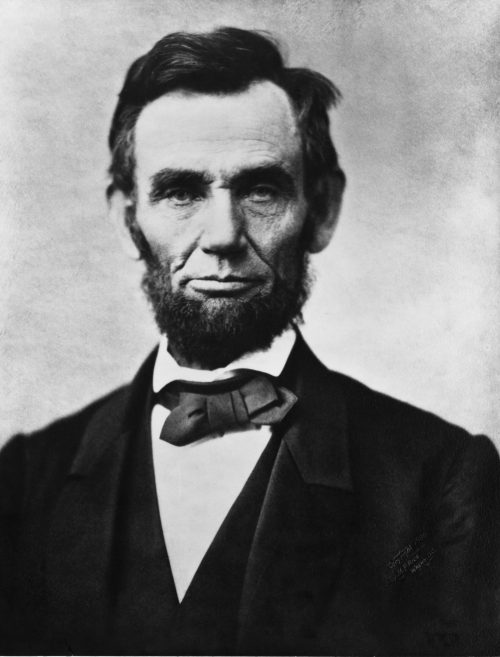

Abraham Lincoln : Civil War and Preservation of the Union

1809-1865.

In the year 1830, or thereabouts, a traveller on the frontier settlements of Illinois (if a traveller was ever known in those dreary regions) might have seen a tall, gaunt, awkward, homely, sad-looking young man of twenty-one, clothed in a suit of brown jean dyed with walnut-bark, hard at work near a log cabin on the banks of the river Sangamon,–a small stream emptying into the Illinois River. The man was splitting rails, which he furnished to a poor woman in exchange for some homespun cloth to make a pair of trousers, at the rate of four hundred rails per yard. His father, one of the most shiftless of the poor whites of Kentucky, a carpenter by trade, had migrated to Indiana, and, after a short residence, had sought another home on a bluff near the Sangamon River, where he had cleared, with the assistance of his son, about fifteen acres of land. From this he gained a miserable and precarious living.

The young rail-splitter had also a knack of slaughtering hogs, for which he received thirty cents a day. Physically he had extraordinary strength, and no one could beat him in wrestling and other athletic exercises. Mentally, he was bright, inquiring, and not wholly illiterate. He had learned, during his various peregrinations, to read, write, and cipher. He was reliable and honest, and had in 1828 been employed, when his father lived in Indiana, by a Mr. Gentry, to accompany his son to New Orleans, with a flat-boat of produce, which he sold successfully.

It is not my object to dwell on the early life of Abraham Lincoln. It has been made familiar by every historian who has written about him, in accordance with the natural curiosity to know the beginnings of illustrious men; and the more humble, the more interesting these are to most people. It is quite enough to say that no man in the United States ever reached eminence from a more obscure origin.

Rail-splitting did not achieve the results to which the ambition of young Lincoln aspired, so he contrived to go into the grocery business; but in this he was unsuccessful, owing to an inherent deficiency in business habits and aptitude. He was, however, gifted with shrewd sense, a quick sense of humor with keen wit, and a marked steadiness of character, which gained him both friends and popularity in the miserable little community where he lived; and in 1832 he was elected captain of a military company to fight Indians in the Black Hawk War. There is no evidence that he ever saw the enemy. He probably would have fought well had he been so fortunate as to encounter the foe; for he was cool, fearless, strong, agile, and active without rashness. In 1833 he was made postmaster of a small village; but the office paid nothing, and his principal profit from it was the opportunity to read newspapers and some magazine trash. He was still very poor, and was surrounded with rough people who lived chiefly on corn bread and salt pork, who slept in cabins without windows, and who drank whiskey to excess, yet who were more intelligent than they seemed.

Such was Abraham Lincoln at the age of twenty-four,–obscure, unknown, poverty-stricken, and without a calling. Suppose at that time some supernatural being had appeared to him in a dream, and announced that he would some day be President of the United States; and not merely this, but that he would rule the nation in a great crisis, and save it from dismemberment and anarchy by force of wisdom and character, and leave behind him when he died a fame second only to that of Washington! Would he not have felt, on awaking from his dream, pretty much as did the aged patriarch whose name he bore, when the angel of the Lord assured him that he would be the father of many nations, that his seed would outnumber the sands of the sea, and that through him all humanity would be blessed from generation to generation? Would he not have felt as the stripling David, among the sheep and the goats of his father’s flocks, when the prophet Samuel announced to him that he should be king over Israel, and rule with such success and splendor that the greatness and prosperity of the Jewish nation would be forever dated from his matchless reign?

The obscure postmaster, without a dollar in his pocket, and carrying the mail in his hat, had indeed no intimation of his future elevation: but his career was just as mysterious as that of David, and an old-fashioned religious man would say that it was equally providential; for of all the leading men of this great nation it would seem that he turned out to be the fittest for the work assigned to him,–chosen, not because he was learned or cultivated or experienced or famous, or even interesting, but because his steps were so ordered that he fell into the paths which naturally led to his great position, although no genius could have foreseen the events which logically controlled the result. If Lincoln had not been gifted with innate greatness, though unknown to himself and all the world, to be developed as occasions should arise, no fortunate circumstances could have produced so extraordinary a career. If Lincoln had not the germs of greatness in him,–certain qualities which were necessary for the guidance of a nation in an emergency,–to be developed subsequently as the need came, then his career is utterly insoluble according to any known laws of human success; and when history cannot solve the mysteries of human success,–in other words, “justify the ways of Providence to man,”–then it loses half its charm, and more than half its moral force. It ceases to be the great teacher which all nations claim it to be.

However obscure the birth of Lincoln, and untoward as were all the circumstances which environed him, he was doubtless born ambitious, that is, with a strong and unceasing desire to “better his condition.” That at the age of twenty-four he ever dreamed of reaching an exalted position is improbable. But when he saw the ascendency that his wit and character had gained for him among rude and uncultivated settlers on the borders of civilization, then, being a born leader of men, as Jackson was, it was perfectly natural that he should aspire to be a politician. Politics ever have been the passion of Western men with more than average ability, and it required but little learning and culture under the sovereignty of “squatters” to become a member of the State legislature, especially in the border States, where population was sparse, and the people mostly poor and ignorant.

Hence, “smart” young men, in rude villages, early learned to make speeches in social and political meetings. Every village had its favorite stump orator, who knew all the affairs of the nation, and a little more, and who, with windy declamation, amused and delighted his rustic hearers. Lincoln was one of these. There was never a time, even in his early career, when he could not make a speech in which there was more wit than knowledge; although as he increased in knowledge he also grew in wisdom, and his good sense, with his habit of patient thinking, gave him the power of clear and convincing statement. Moreover, at twenty-four, he was already tolerably intelligent, and had devoured all the books he could lay his hand upon. Indeed, it was to the reading of books that Lincoln, like Henry Clay, owed pretty much all his schooling. Beginning with Weems’s “Life of Washington” when a mere lad, he perseveringly read, through all his fortunes, all manner of books,–not only during leisure hours by day, when tending mill or store, but for long months by the light of pine shavings from the cooper’s shop at night, and in later times when traversing the country in his various callings. And his persistent reading gave him new ideas and broader views.

With his growing thoughts his aspirations grew. So, like others, he took the stump, and as early as 1832 offered himself a candidate for the State legislature. His maiden speech in an obscure village is thus reported: “Fellow citizens, I am humble Abraham Lincoln. My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a National Bank, of internal improvements, and a high protective tariff. These are my sentiments. If elected, I shall be thankful; if not, it will be all the same.”

Lincoln was not elected, although supported by the citizens of New Salem, where he lived, and to whom he had promised the improvement of the Sangamon River. Disappointed, he went into the grocery business once again, and again failed, partly because he had no capital, and partly because he had no business talents in that line; although from his known integrity he was able to raise what money he needed. He then set about the study of the law, as a step to political success, read books, and the occasional newspapers, told stories, and kept his soul in patience,–which was easier to him than to keep his body in decent clothes.

It was necessary for him to do something for a living while he studied law, since the grocery business had failed, and hence he became an assistant to John Calhoun, the county surveyor, who was overburdened with work. Just as he had patiently worked through an English Grammar, to enable him to speak correctly, he took up a work on surveying and prepared himself for his new employment in six weeks. He was soon enabled to live more decently, and to make valuable acquaintances, meanwhile diligently pursuing his law studies, not only during his leisure, but even as he travelled about the country to and from his work; on foot or on horseback, his companion was sure to be a law-book.

In 1834 a new election of representatives for the State legislature took place, and Lincoln became a candidate,–this time with more success, owing to the assistance of influential friends. He went to Vandalia, the State capital, as a Whig, and a great admirer of Henry Clay. He was placed on the Committee of Public Accounts and Expenditures, but made no mark; yet that he gained respect was obvious from the fact that he was re-elected by a very large vote. He served a second term, and made himself popular by advocating schemes to “gridiron” every county with railroads, straighten out the courses of rivers, dig canals, and cut up the State into towns, cities, and house-lots. One might suppose that a man so cool and sensible as he afterwards proved himself to be must have seen the absurdity of these wild schemes, and hence only fell in with them from policy as a rising member of the legislature, to gain favor with his constituents. Yet he and his colleagues were all crude and inexperienced legislators, and it is no discredit to Lincoln that he was borne along with the rest in an enthusiasm for “developing the country.” The mania for speculation was nearly universal, especially in the new Western States. Illinois alone projected 1,350 miles of railroad, without money and without credit to carry out this Bedlam legislation, and in almost every village there were “corner lots” enough to be sold to make a great city. Aside from this participation in a bubble destined to burst, and to be followed by disasters, bankruptcies, and universal distress, Lincoln was credited with steadiness, and gained great influence. He was prominent in securing the passage of a bill which removed the seat of government to Springfield, and was regarded as a good debater. In this session, too, he and Daniel Stone, the two representatives from Sangamon County, introduced a resolution declaring that the institution of slavery was “founded on both injustice and bad policy;” that the Congress had no power to interfere with slavery in the States; that it had power in the District of Columbia, but should not exercise it unless at the request of the people of the District. There were no votes for these resolutions, but it is interesting to see how early Lincoln took both moral and constitutional ground concerning national action on this vexed question.

In March, 1837, Lincoln, then twenty-eight years old, was admitted to the bar, and made choice of Springfield, the new capital, as a residence, then a thriving village of one or two thousand inhabitants, with some pretension to culture and refinement. It was certainly a political, if not a social, centre. The following year he was again elected to the legislature, and came within a few votes of being made Speaker of the House. He carried on the practice of the law with his duties as a legislator. Indeed, law and politics went hand in hand; as a lawyer he gained influence in the House of Representatives, and as a member of the legislature he increased his practice in the courts. He had for a partner a Major Stuart, who in 1841 left him, having been elected Representative in Congress, and was succeeded in the firm by Stephen T. Logan. Lincoln’s law practice was far from lucrative, and he was compelled to live in the strictest economy. Litigation was very simple, and it required but little legal learning to conduct cases. The lawyers’ fees were small among a people who were mostly poor. Considering, however, his defective education and other disadvantages, Lincoln’s success as a lawyer was certainly respectable, if not great, in his small sphere.

In 1840, three years after his admission to the bar, Lincoln was chosen as an elector in the Harrison presidential contest, and he stumped the State, frequently encountering Stephen A. Douglas in debate, with great credit to himself, for Douglas was the most prominent political orator of the day. The heart of Lincoln, from the start, was in politics rather than the law, for which he had no especial liking. He was born to make speeches in political gatherings, and not to argue complicated legal questions in the courts. All his aspirations were political. As early as 1843 he aspired to be a member of Congress, but was defeated by Colonel Baker. In 1846, however, his political ambition was gratified by an election to the House of Representatives. His record in Congress was a fair one; but he was not distinguished, although great questions were being discussed in connection with the Mexican War. He made but three speeches during his term, in the last of which he ridiculed General Cass’s aspiration for the presidency with considerable humor and wit, which was not lost on his constituents. His career in Congress terminated in 1848, he not being re-elected.

In the meantime Lincoln married, in 1842, Miss Mary Todd, from Lexington, Kentucky, a lady of good education and higher social position than his own, whom he had known for two or three years. As everybody knows, this marriage did not prove a happy one, and domestic troubles account, in a measure, for Lincoln’s sad and melancholy countenance. Biographers have devoted more space than is wise to this marriage since the sorrows of a great man claim but small attention compared with his public services. Had Lincoln not been an honorable man, it is probable that the marriage would never have taken place, in view of incompatibilities of temper which no one saw more clearly than he himself, and which disenchanted him. The engagement was broken, and renewed, for, as the matter stood,–the lady being determined and the lover uncertain,–the only course consistent with Lincoln’s honor was to take the risk of marriage, and devote himself with renewed ardor to his profession,–to bury his domestic troubles in work, and persistently avoid all quarrels. And this is all the world need know of this sad affair, which, though a matter of gossip, never was a scandal. It is unfortunate for the fame of many great men that we know too much of their private lives. Mr. Froude, in his desire for historical impartiality, did no good to the memory of his friend Carlyle. Had the hero’s peculiarities been vices, like those of Byron, the biographer might have cited them as warnings to abate the ardor of popular idolatry of genius. If we knew no more of the private failings of Webster than we do of those of Calhoun or Jefferson Davis, he might never have been dethroned from the lofty position he occupied, which, as a public benefactor, he did not deserve to lose.

After his marriage, Lincoln was more devoted to his profession, and gradually became a good lawyer; but I doubt if he was ever a great one, like his friend Judge Davis. His law partner and biographer, William H. Herndon, who became associated with him in 1845, is not particularly eulogistic as to his legal abilities, although he concedes that he had many of the qualities of a great lawyer, such as the ability to see important points, lucidity of statement, and extraordinary logical power. He did not like to undertake the management of a case which had not justice and right on its side. He had no method in his business, and detested mechanical drudgery. He rarely studied law-books, unless in reference to a case in which he was employed. He was not learned in the decisions of the higher courts. He was a poor defender of a wrong cause, but was unappalled by the difficulties of an intricate case; was patient and painstaking, and not imposed upon by sophistries.

Lincoln’s love of truth, for truth’s sake, even in such a technical matter as the law, was remarkable. No important error ever went undetected by him. His intellectual vision was clear, since he was rarely swayed by his feelings. As an advocate he was lucid, cold, and logical, rather than rhetorical or passionate. He had no taste for platitudes and “glittering generalities.” There was nothing mercenary in his practice, and with rare conscientiousness he measured his charges by the services rendered, contented if the fees were small. He carried the strictest honesty into his calling, which greatly added to his influence. If there was ever an honest lawyer he was doubtless one. Even in arguing a case, he never misrepresented the evidence of a witness, and was always candid and fair. He would frequently, against his own interest, persuade a litigant of the injustice of his case, and induce him to throw it up. If not the undisputed leader of his circuit, he was the most beloved. Sometimes he disturbed the court by his droll and humorous illustrations, which called out irrepressible laughter but generally he was grave and earnest in matters of importance; and he was always at home in the courtroom, quiet, collected, and dignified, awkward as was his figure and his gesticulation.

But it was not as a lawyer that Lincoln was famous. Nor as a public speaker would he compare with Douglas in eloquence or renown. As a member of Congress it is not probable that he would ever have taken a commanding rank, like Clay or Webster or Calhoun, or even like Seward. His great fame rests on his moral character, his identification with a great cause, his marvellous ability as a conservative defender of radical principles, and his no less wonderful tact as a leader of men.

The cause for which he stands was the Antislavery movement, as it grew into a political necessity rather than as a protest against moral evil. Although from his youth an antislavery man, Lincoln was not an Abolitionist in the early days of the slavery agitation. He rather kept aloof from the discussion, although such writers as Theodore Parker, Dr. Channing, and Horace Greeley had great charm for him. He was a politician, and therefore discreet in the avowal of opinions. His turn of mind was conservative and moderate, and therefore he thought that all political action should be along the lines established by law under the Constitution.

But when the Southern leaders, not content with non-interference by Congress with their favorite institution in their own States, sought to compel Congress to allow the extension of slavery in the Territories it controlled, then the indignation of Lincoln burst the bounds, and he became the leader in his State in opposition to any movement to establish in national territory that institution “founded on both injustice and bad policy.” Although he was in Congress in 1847-8, his political career really began about the year 1854, four years after the death of Calhoun.

As has been shown in previous chapters, the great slavery agitation of 1850, when the whole country was convulsed by discussions and ominous threats of disunion, was laid at rest for a while by the celebrated compromise bill which Henry Clay succeeded in passing through Congress. By the terms of this compromise California was admitted to the Union as a free State; the Territories of New Mexico and Utah were organized to come in as States, with or without slavery as their people might determine when the time should arrive; the domestic slave-trade in the District of Columbia was abolished; a more stringent fugitive-slave law was passed; and for the adjustment of State boundaries, which reduced the positive slave-area in Texas and threw it into the debatable territory of New Mexico, Texas received ten millions of dollars. Although this adjustment was not entirely satisfactory to either the North or the South, the nation settled itself for a period of quiet to repair the waste and utilize the conquests of the Mexican War. It became absorbed in the expansion of its commerce, the development of its manufactures, and the growth of its emigration, all quickened by the richness of its marvellous new gold-fields,–until, unexpectedly and suddenly, it found itself once again plunged into political controversy more distracting and more ominous than the worst it had yet experienced.

For, while calmly accepting the divers political arrangements made for distant States and Territories, the men of the North, who had fumed and argued against the passage of the Fugitive-Slave Law, when its enforcement was attempted in their very presence were altogether outraged. When the “man-hunters” chased and caught negroes in their village market-places and city streets, when free men were summoned to obey that law by helping to seize trembling fugitives and send them back to worse than death, then they burst forth in a fierce storm of rage that could not be quieted. The agitation rose and spread; lecturers thundered; newspapers denounced; great meetings were held; politicians trembled. And even yet the conservatism of the North was not wholly inflamed; for political partisanship is in itself a kind of slavery, and while the Northern Democrats stood squarely with the South, the Northern Whigs, fearing division and defeat, made strenuous efforts to stand on both sides, and, admitting slavery to be an “evil,” to uphold the Fugitive-Slave Law because it was a part of the “great compromise.” In Congress and out, in national conventions, and with all the power of the party press, this view was strenuously advocated; but in 1852 the Democrats elected Franklin Pierce as President, while the compromising Whigs were cast out. Webster, the leader of the compromisers, had not even secured a nomination, but General Scott was the Whig candidate; while William H. Seward, at the head of the Antislavery Whigs, had at least the satisfaction of seeing that, amid the dissolving elements of the Whig party, the antislavery sentiment was gaining strength day by day. The old issues of tariffs and internal improvements were losing their vitality, while Freedom and Slavery were the new poles about which new crystallizations were beginning to form.

But the Compromise of 1850 had loosed from its Pandora’s box another fomenter of trouble, in the idea of leaving to the people of the Territories the settlement of whether their incoming States should be slave or free,–the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” as it was called. The nation had accepted that theory as a makeshift for the emergency of that day; but slave cultivation had already exhausted much of the Southern land, and, not content with Utah and New Mexico for their propagandism, the slaveholders cast envious eyes upon the great territory of the Northwest, stretching out from the Missouri border, although it was north of the prohibited line of 36° 30′. And so it came about that, within four short years after the compromise of 1850, the unrest of the North under the Fugitive-Slave Law, followed by the efforts of the South to break down the earlier compromise of 1821, awoke again with renewed fierceness the slavery agitation, in discussing the bill for the organization of the Territories of Kansas and Nebraska,–an immense area, extending from the borders of Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota, west to the Rocky Mountains, and from the line of 36° 30′ north to British America.

The mover of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, Stephen A. Douglas, Senator from Illinois, a Democrat and a man of remarkable abilities, now came into prominent notice. He wanted to be President of the United States, and his popularity, his legal attainments, his congressional services, his attractive eloquence and skill in debate, marked him out as the rising man of his party, He was a Vermonter by birth, and like Lincoln had arisen from nothing,–a self-made man, so talented that the people called him “the little giant,” but nevertheless inferior to the giants who had led the Senate for twenty years, while equal to them in ambition, and superior as a wire-pulling politician. He was among those who at first supposed that the Missouri Compromise of 1821 was a final settlement, and was hostile to the further agitation of the slavery question. He was a great believer in “American Destiny,” and the absorption of all North America in one grand confederation, in certain portions of which slavery should be tolerated. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories he had great influence in opening new routes of travel, and favored the extension of white settlements, even in territory which had been given to the Indians.

To further his ambitious aspirations, Douglas began now to court the favor of Southern leaders, and introduced his famous Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which was virtually the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, inasmuch as it opened the vast territories to the north of 36° 30′ to the introduction of slavery if their people should so elect. This the South needed, to secure what they called the balance of power, but what was really the preponderance of the Slave States, or at least the curtailment of the political power of the Free States. In 1854, during the administration of Franklin Pierce, and under the domination of the Democratic party, which played into the hands of the Southern leaders, the compromise which Clay had effected in 1821 was repealed under the influence of his compromise of 1850, and the slavery question was thus reopened for political discussion in every State of the Union,–showing how dangerous it is to compromise principle in shaping a policy.

Popular indignation at the North knew no bounds at this new retrograde movement. The Whigs uttered protests, while the Free-Soil party, just coming into notice, composed mainly of moderate antislavery men from both the old parties, were loud in their denunciations of the encroachments of the South. Even some leading Democrats opened their eyes, and joined the rising party. The newspapers, the pulpits, and the platforms sent forth a united cry of wrath. The Whigs and the Abolitionists were plainly approaching each other. The year 1854 saw a continuous and solid political campaign to repress the further spread of slavery. The Territories being then thrown open, there now began an intense emulation to people them, on the one hand, with advocates of slavery, and on the other, with free-soilers. Emigration societies were founded to assist bona fide settlers, and a great tide of families poured into Kansas from the Northern States; while the Southern States, and chiefly Missouri, sent also large numbers of men.

At the South the repeal of the Missouri Compromise was universally welcomed, and the Southern leaders felt encouragement and exultation. The South had gained a great victory, aided by Northern Democrats, and boldly denounced Chase, Hale, Sumner, Seward, and Giddings in the Congress as incendiaries, plotting to destroy precious rights. A memorable contest took place in the House of Representatives to prevent the election of Banks of Massachusetts as Speaker. But the tide was beginning to turn, and Banks, by a vote of 113 against 104, obtained the Speakership.

Then followed “border ruffianism” in Kansas, when armed invaders from Missouri, casting thousands of illegal votes, elected, by fraud and violence, a legislature favorable to slavery, accompanied with civil war, in which the most disgraceful outrages were perpetrated, the central government at Washington being blind and deaf and dumb to it all. The bona fide settlers in Kansas who were opposed to slavery then assembled at Topeka, refused to recognize the bogus laws, and framed a constitution which President Pierce–“a Northern man with Southern principles,” gentlemanly and cultivated, but not strong–pronounced to be revolutionary. Nor was ruffianism confined to Kansas. In 1856 Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, one of the most eloquent and forceful denunciators of all the pro-slavery lawlessness, was attacked at his desk in the Senate chamber, after an adjournment, and unmercifully beaten with a heavy cane by Preston Brooks, a member of the House of Representatives, and nephew of Senator Butler of South Carolina. It took years for Sumner to recover, while the aristocratic ruffian was unmolested, and went unpunished; for, though censured by the House and compelled to resign his seat, he was immediately re-elected by his constituents.

But this was not all. In that same year the Supreme Court came to the aid of the South, already supported by the Executive and the Senate. Six judges out of nine, headed by Chief Justice Taney, pronounced judgment that slaves, whether fugitive or taken by their masters into the free States, should be returned to their owners. This celebrated case arose in Missouri, where a negro named Dred Scott–who had been taken by his master to States where slavery was prohibited by law, who had, with his master’s consent, married and had children in the free States, and been brought back to Missouri–sued for his freedom. The local court granted it; the highest court of the State reversed the decision; and on appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States the case was twice argued there, and excited a wide and deep interest. The court might have simply sent it back, as a matter belonging to the State court to decide; but it permitted itself to argue the question throughout, and pronounced on the natural inferiority of the negro, and his legal condition as property, the competence of the State courts to decide his freedom or slavery, and the right of slaveholders under the Constitution to control their property in the free States or Territories, any legislation by Congress or local legislatures to the contrary notwithstanding. This was the climax of slavery triumphs. The North and West, at last aroused, declared in conventions and legislative halls that slavery should advance no further. The conflict now indeed became “irrepressible.”

At this crisis, Abraham Lincoln stepped upon the political stage, and his great career began.

As a local lawyer, even as a local politician, his work was practically done. He came forth as an avowed antagonist of Douglas, who was the strongest man in Illinois, and the leader of the Democratic party in Congress. He came forth as the champion of the antislavery cause in his native State, and soon attracted the eyes of the whole nation. His memorable controversy with Douglas was the turning-point of his life. He became a statesman, as well as a patriot, broad, lofty, and indignant at wrongs. Theretofore he had been a conservative Whig, a devoted follower of Clay. But as soon as the Missouri Compromise was repealed he put forth his noblest energies in behalf of justice, of right, and of humanity.

As he was driving one day from a little town in which court had been held, a brother lawyer said to him, “Lincoln, the time is coming when we shall either be Abolitionists or Democrats;” to which he replied, musingly, “When that time comes, my mind is made up, for I believe the slavery question can never be successfully compromised.” And when his mind was made up, after earnest deliberation, he rarely changed it, and became as firm as a rock. His convictions were exceedingly strong, and few influences could shake them. That quiet conversation in his buggy, in a retired road, with a brother lawyer, was a political baptism. He had taken his stand on one side of a great question which would rend in twain the whole country, and make a mighty conflagration, out of whose fires the truth should come victorious.

The Whig party was now politically dead, and the Republican party arose, composed of conscientious and independent-minded men from all the old organizations, not afraid to put principle before party, conservative and law-abiding, yet deeply aroused on the great issue of the day, and united against the further extension of slavery,–organizing with great enthusiasm for a first presidential campaign in 1856, under Frémont, “the Pathfinder,” as their candidate. They were defeated, and James Buchanan, the Democratic candidate, became President; but, accepting defeat as a lesson toward victory, they grew stronger and stronger every day, until at last they swept the country and secured to the principle “non-extension of slavery” complete representation in the national government.

Lincoln, who was in 1857 the Republican candidate for United States Senator from Illinois, while Douglas sought the votes of the Democracy, first entered the lists against his rival at Springfield, in a speech attacking that wily politician’s position as to the Dred-Scott decision. He tried to force Douglas to a declaration of the logical consequence of his position, namely, that, while he upheld the decision as a wise interpretation of the rights of the slave-owners to hold slaves in the Territories, yet the people of a Territory, under “the great principle of Popular Sovereignty” (which was Douglas’s chief stock in trade), could exclude slavery from its limits even before it had formed a State constitution. “If we succeed in bringing him to this point,” he wrote a friend, “he will say that slavery cannot actually exist in the Territories unless the people desire it, which will offend the South.” If Douglas did not answer Lincoln’s question he would jeopardize his election as Senator; if he did answer he would offend the South, for his doctrine of “squatter sovereignty” conflicted not only with the interests of slavery, but with his defence of the Dred-Scott decision,–a fact which Lincoln was not slow to point out. Douglas did answer, and the result was as Lincoln predicted.

The position taken by Lincoln himself in the debate was bold and clear. Said he, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure half-slave and half-free. Either the opponents of slavery will avert the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States,–old as well as new, North as well as South.” When his friends objected that this kind of talk would defeat him for senatorship, he replied, “But it is true … I would rather be defeated with these expressions in my speech held up and discussed before the people than be victorious without it.” He was defeated: but the debates made his fame national and resulted in his being president; while the politic Douglas gained the senatorship and lost the greater prize.

In these famous debates between the leaders, Lincoln proved himself quite the equal of his antagonist, who was already famous as a trained and prompt debater. Lincoln canvassed the State. He made in one campaign as many as fifty speeches. It is impossible, within my narrow limits, to go into the details of those great debates. In them Lincoln rose above all technicalities and sophistries, and not only planted himself on eternal right, but showed marvellous political wisdom. The keynote of all his utterances was that “a house divided against itself could not stand.” Yet he did not pass beyond the constitutional limit in his argument: he admitted the right of the South to a fugitive-slave law, and the right of a Territory to enact slavery for itself on becoming a State; he favored abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia only on the request of its inhabitants, and would forward the colonization of the negroes in Liberia if they wished it and their masters consented. He was a pronounced antislavery man, but not an Abolitionist, and took with the great mass of the Northerners a firm stand against the extension of slavery. It was this intuitive perception of the common-sense of the situation that made him and kept him the remarkable representative of the Northern people that he was to the very end.

Lincoln gained so much fame from his contest with Douglas that he was, during the spring of the following year, invited to speak in the Eastern States; and in the great hall of the Cooper Institute in New York, in February, 1860, he addressed a magnificent audience presided over by Bryant the poet. He had made elaborate preparation for this speech, which was a careful review of the slavery question from the foundation of the republic to that time, and a masterly analysis of the relative positions of political parties to it. The address made a deep impression. The speaker was simply introduced as a distinguished politician from the West. The speech was a surprise to those who were familiar with Western oratory. There was no attempt at rhetoric, but the address was pure logic from beginning to end, like an argument before the Supreme Court, and exceedingly forcible. The chief point made was the political necessity of excluding slavery from the Territories. The orator did not dwell on slavery as a crime, but as a wrong which had gradually been forced upon the nation, the remedy for which was not in violent denunciations. He did not abuse the South; he simply pleaded for harmony in the Republican ranks, and avoided giving offence to extreme partisans on any side, contending that if slavery could be excluded from the Territories it would gradually become extinct, as both unprofitable and unjust. He would tolerate slavery within its present limits, and even return fugitive slaves to their owners, according to the laws, but would not extend the evil where it did not at present exist. As it was a wrong, it must not be perpetuated.

The moderation of this speech, coming from an Illinois politician, did much to draw attention to him as a possible future candidate for the presidency, to which, by this time, he undoubtedly aspired. And why not? He was the leader of his party in Illinois, a great speech-maker, who had defeated Douglas himself in debate, a shrewd, cool, far-sighted man, looking to the future rather than the present; and political friends had already gathered about him as a strong political factor.

Mr. Lincoln after his great speech in New York returned to his home. He had a few years before given some political speeches in Boston and the adjacent towns, which were well received, but made no deep impression,–from no fault of his, but simply because he had not the right material to work upon, where culture was more in demand than vigor of intellect.

Indeed, one result of the election of Lincoln, and of the war which followed, was to open the eyes of Eastern people to the intellect and intelligence of the West. Western lawyers and politicians might not have the culture of Sumner, the polished elocution of Everett, the urbanity of Van Buren, and the courtly manners of Winthrop, but they had brain-power, a faculty for speech-making, and great political sagacity. And they were generally more in sympathy with the people, having mostly sprung from their ranks. Their hard and rugged intellects told on the floor of Congress, where every one is soon judged according to his merits, and not according to his clothes. And the East saw that thereafter political power would centre in the West, and dominate the whole country,–against which it was useless to complain or rebel, since, according to all political axioms, the majority will rule, and ought to rule. And the more the East saw of the leading men of the West, the more it respected their force of mind, their broad and comprehensive views, and their fitness for high place under the government.

It was not the people of the United States who called for the nomination of Lincoln, as in the case of General Jackson. He was not much known outside of Illinois, except as a skilful debater and stump orator. He had filled no high office to bring him before the eyes of the nation. He was not a general covered with military laurels, nor a Senator in Congress, nor governor of a large State, nor a cabinet officer. No man had thus far been nominated for President unless he was a military success, or was in the line of party promotion. Though a party leader in Illinois, Lincoln was simply a private citizen, with no antecedents which marked him out for such exalted position. But he was “available,”–a man who could be trusted, moderate in his views, a Whig and yet committed to antislavery views, of great logical powers, and well-informed on all the political issues of the day. He was not likely to be rash, or impulsive, or hasty, or to stand in the way of political aspirants. He was eminently a safe man in an approaching crisis, with a judicial intellect, and above all a man without enemies, whom few envied, and some laughed at for his grotesque humor and awkward manners. He was also modest and unpretending, and had the tact to veil his ambition. In his own State he was exceedingly popular. It was not strange, therefore, that the Illinois Republican State Convention nominated him as their presidential candidate, to be supported in the larger national convention about to assemble.

In May, 1860, the memorable National Republican Convention met in Chicago, in an immense building called the Wigwam, to select a candidate for the presidency. Among the prominent Republican leaders were Seward, Chase, Cameron, Dayton, and Bates. The Eastern people supposed that Seward would receive the nomination, from his conceded ability, his political experience, his prominence as an antislavery Whig, and the prestige of office; but he had enemies, and an unconciliatory disposition. It soon became evident that he could not carry all the States. The contest was between Seward, Chase, and Lincoln; and when, on the third ballot, Lincoln received within a vote and a-half of the majority, Ohio gave him four votes from Chase, and then delegation after delegation changed its vote for the victor, and amid great enthusiasm the nomination became unanimous.

The election followed, and Lincoln, the Republican, received one hundred and eighty electoral votes; Breckinridge, the Southern Democrat, seventy-two; Bell, of the Union ticket–the last fragment of the old Whig party–thirty-nine; and Douglas, of the Northern Democracy, but twelve. The rail-splitter became President of the United States, and Senator Hannibal Hamlin, of Maine, Vice President. It was a victory of ideas. It was the triumph of the North over the South,–of the aroused conscience and intelligence of the people against bigotry, arrogance, and wrong. Men and measures in that great contest paled before the grandeur of everlasting principles. It was not for Lincoln that bonfires were kindled and cannons roared and bells were rung and huzzas ascended to heaven, but for the great check given to the slave-power, which, since the formation of the Constitution, had dominated the nation. The Republicans did not gain a majority of the popular vote, as the combined opposing tickets cast 930,170 votes more than they; but their vote was much larger than that for any other ticket, and gave them a handsome majority in the electoral college.

Between the election in November, 1860, and the following March, when Lincoln took the reins of government, several of the Southern States had already seceded from the Union and had organized a government at Montgomery. Making the excuse of the election of a “sectional and minority president,” they had put into effect the action for which their leaders during several months had been secretly preparing. They had seized nearly all the Federal forts, arsenals, dock-yards, custom-houses, and post-offices within their limits, while a large number of the officers of the United States army and navy had resigned, and entered into their service, on the principle that the authority of their States was paramount to the Federal power.

Amid all these preparations for war on the part of the seceding States, and the seizure of Federal property, Buchanan was irresolute and perplexed. He was doubtless patriotic and honest, but he did not know what to do. The state of things was much more serious than when South Carolina threatened to secede in the time of General Jackson. The want of firmness and decision on the part of the President has been severely criticised, but it seems to me to have been not without excuse in the perplexing conditions of the time, while it was certainly fortunate that he did not precipitate the crisis by sending troops to reinforce Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, which was invested and threatened by South Carolina troops. The contest was inevitable anyway, and the management of the war was better in the hands of Lincoln than it could have been in those of Buchanan, with traitors in his cabinet, or even after they had left and a new and loyal cabinet was summoned, but with an undecided man at the head. There was needed a new and stronger government when hostilities should actually break out.

On the 4th of March, 1861, the inauguration of Lincoln took place, and well do I remember the ceremony. The day was warm and beautiful, and nature smiled in mockery of the bloody tragedy which was so soon to follow. I mingled with the crowd at the eastern portico of the Capitol, and was so fortunate as to hear and see all that took place,–the high officials who surrounded the President, his own sad and pensive face, his awkward but not undignified person arrayed in a faultless suit of black, the long address he made, the oath of office administered by Chief Justice Taney, and the dispersion of the civil and military functionaries to their homes. It was not a great pageant, but was an impressive gathering. Society, in which the Southern element predominated, sneered at the tall ruler who had learned so few of its graces and insincerities, and took but little note of the thunder-clouds in the political atmosphere,–the distant rumblings which heralded the approaching storm so soon to break with satanic force.

The inaugural address was not only an earnest appeal for peace, but a calm and steadfast announcement of the law-abiding policy of the government, and a putting of the responsibility for any bloodshed upon those who should resist the law. Two brief paragraphs contain the whole:–

“The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects there will be no invasion, no use of force among the people anywhere.

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.”

This was the original chart of the course which the President followed, and his final justification when by use of “the power confided to him” he had accomplished the complete restoration of the authority of the Federal Union over all the vast territory which the seceded States had seized and so desperately tried to control.

Lincoln was judicious and fortunate in his cabinet. Seward, the ablest and most experienced statesman of the day, accepted the office of Secretary of State; Salmon P. Chase, who had been governor of Ohio, and United States Senator, was made Secretary of the Treasury; Gideon Welles, of great executive ability and untiring energy, became Secretary of the Navy; Simon Cameron, an influential politician of Pennsylvania, held the post of Secretary of War for a time, when he was succeeded by Edwin M. Stanton, a man of immense capacity for work; Montgomery Blair, a noted antislavery leader, was made Postmaster-General; Caleb B. Smith became Secretary of the Interior; and Edward Bates, of Missouri, Attorney-General. Every one of these cabinet ministers was a strong man, and was found to be greater than he had seemed.

Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi, an old-time Democrat, was elected President of the Southern Confederacy, and Alexander H. Stephens, a prominent Whig of Georgia, Vice-President. Davis was born in Kentucky in 1808, and was a graduate of West Point. He was a Congressman on the outbreak of the Mexican War, resigned his seat, entered the army, and distinguished himself, rising to the rank of colonel. He was Secretary of War in President Pierce’s cabinet, and Senator from Mississippi on the accession of President Buchanan,–a position which he held until the secession of his State. He thus had had considerable military and political experience. He was a man of great ability, but was proud, reserved, and cold, “a Democrat by party name, an autocrat in feeling and sentiment,–a type of the highest Southern culture, and exclusive Southern caste.” To his friends–and they were many, in spite of his reserve–there was a peculiar charm in his social intercourse; he was beloved in his family, and his private life was irreproachable. He selected an able cabinet, among whom were Walker of Alabama, Toombs of Georgia, and Benjamin of Louisiana. The Provisional Congress authorized a regular army of ten thousand men, one hundred thousand volunteers, and a loan of fifteen millions of dollars.

But actual hostilities had not as yet commenced. The Confederates, during the close of Buchanan’s administration, were not without hopes of a peaceful settlement and recognition of secession, and several conferences had taken place,–one overture being made even to the new administration, but of course in vain.

The spark which kindled the conflagration–but little more than a month after Lincoln’s inauguration, April 12, 1861–was the firing on Fort Sumter, and its surrender to the South Carolinians. This aroused both the indignation and the military enthusiasm of the North, which in a single day was, as by a lightning flash, fused in a white heat of patriotism and a desire to avenge the dishonored flag. For the time all party lines disappeared, and the whole population were united and solid in defence of the Union. Both sides now prepared to fight in good earnest. The sword was drawn, the scabbard thrown away. Both sides were confident of victory. The Southern leaders were under the delusion that the Yankees would not fight, and that they cared more for dollars than for their country. Moreover, the Southern States had long been training their young men in the military schools, and had for months been collecting materials of war. As cotton was an acknowledged “king,” the planters calculated on the support of England, which could not do without their bales. Lastly, they knew that the North had been divided against itself, and that the Democratic politicians sympathized with them in reference to slavery. The Federal leaders, on the other hand, relied on the force of numbers, of wealth, and national prestige. Very few supposed that the contest would be protracted. Seward thought that it would not last over three months. Nor did the South think of conquering the North, but supposed it could secure its own independence. It certainly was resolved on making a desperate fight to defend its peculiar institution. As it was generally thought in England that this attempt would succeed, as England had no special love for the Union, and as the Union, and not opposition to slavery, was the rallying cry of the North, England gave to the South its moral support.

Lincoln assumed his burden with great modesty, but with a steady firmness and determination, and surprised his cabinet by his force of will. Nicolay and Hay relate an anecdote of great significance. Seward, who occupied the first place in the cabinet, which he deserved on account of his experience and abilities, was not altogether pleased with the slow progress of things, and wrote to Lincoln an extraordinary letter in less than a month after his inauguration, suggesting more active operations, with specific memoranda of a proposed policy. “Whatever policy we adopt,” said he, “there must be an energetic prosecution of it. For this purpose it must be somebody’s business to pursue and direct it incessantly. Either the President must do it himself, or devolve it on some member of his cabinet. It is not my especial province; but I neither seek to evade nor assume responsibility.” In brief, it was an intimation, “If you feel not equal to the emergency, perhaps you can find a man not a thousand miles away who is equal to it.”

Lincoln, in his reply, showed transcendent tact. Although an inexperienced local politician, suddenly placed at the head of a great nation, in a tremendous crisis, and surrounded in his cabinet and in Congress by men of acknowledged expert ability in statecraft, he had his own ideas, but he needed the counsel and help of these men as well. He could not afford to part with the services of a man like Seward, nor would he offend him by any assumption of dignity or resentment at his unasked advice. He good-naturedly replied, in substance: “The policy laid down in my inaugural met your distinct approval, and it has thus far been exactly followed. As to attending to its prosecution, if this must be done, I must do it, and I wish, and suppose I am entitled to have, the advice of all the cabinet.”

After this, no member of the cabinet dared to attempt to usurp any authority which belonged to the elected Commander-in-chief of the army and navy,–unless it were Chase, at a later time. As the head of the government in whom supreme Federal power was invested in time of war, Lincoln was willing and eager to consult his cabinet, but reserved his decisions and assumed all responsibilities. He probably made mistakes, but who could have done better on the whole? The choice of the nation was justified by results.

It is not my object in this paper to attempt to compress the political and military history of the United States during the memorable administration of Mr. Lincoln. If one wishes to know the details he must go to the ten octavo biographical volumes of Lincoln’s private secretaries, to the huge and voluminous quarto reports of the government, to the multifarious books on the war and its actors. I can only glance at salient points, and even here I must confine myself to those movements which are intimately connected with the agency and influence of Lincoln himself. It is his life, and not a history of the war, that it is my business to present. Nor has the time come for an impartial and luminous account of the greatest event of modern times. The jealousy and dissensions of generals, the prejudices of the people both North and South, the uncertainty and inconsistency of much of the material published, and the conceit of politicians, alike prevent a history which will be satisfactory, no matter how gifted and learned may be the historian. When all the actors of that famous tragedy, both great and small, have passed away, new light will appear, and poetry will add her charms to what is now too hideous a reality, glorious as were the achievements of heroes and statesmen.

After the Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861, won by the Confederate General Beauregard over General McDowell, against all expectation, to the dismay and indignation of the whole North,–the result of over-confidence on the part of the Union troops, and a wretchedly mismanaged affair,–the attention of the Federal government was mainly directed to the defence of Washington, which might have fallen into the hands of the enemy had the victors been confident and quick enough to pursue the advantage they had gained; for nothing could exceed the panic at the capital after the disastrous defeat of McDowell. The demoralization of the Union forces was awful. Happily, the condition of the Confederate troops was not much better.

But the country rallied after the crisis had passed. Lincoln issued his proclamation for five hundred thousand additional men. Congress authorized as large a loan as was needed. The governors of the various States raised regiment after regiment, and sent them to Washington, as the way through Maryland, at first obstructed by local secessionists, was now clear, General Butler having intrenched himself at Baltimore. Most fortunately the governor of Maryland was a Union man, and with the aid of the Northern forces had repressed the rebellious tendency in Maryland, which State afterward remained permanently in the Union, and offered no further resistance to the passage of Federal troops. Arlington Heights in Virginia, opposite Washington, had already been fortified by General Scott; but additional defences were made, and the capital was out of danger.

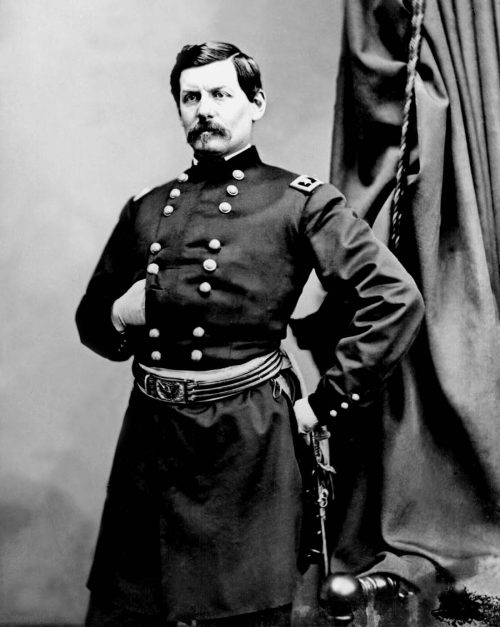

With the rapid concentration of troops at Washington, the government again assumed the offensive. General George B. McClellan, having distinguished himself in West Virginia, was called to Washington, at the recommendation of the best military authorities, and intrusted with the command of the Army of the Potomac; and soon after, on the retirement of General Scott, now aged and infirm, and unable to mount a horse, McClellan took his place as commander of all the forces of the United States.

At the beginning of the rebellion McClellan was simply a captain, but was regarded as one of the most able and accomplished officers of the army. His promotion was rapid beyond precedent; but his head was turned by his elevation, and he became arrogant and opinionated, and before long even insulted the President, and assumed the airs of a national liberator on whose shoulders was laid the burden of the war. He consequently estranged Congress, offended Scott, became distrusted by the President, and provoked the jealousies of the other generals. But he was popular with the army and his subordinates, and if he offended his superiors his soldiers were devoted to him, and looked upon him as a second Napoleon.

The best thing that can be said of this general is that he was a great organizer, and admirably disciplined for their future encounters the raw troops which were placed under his command. And he was too prudent to risk the lives of his men until his preparations were made, although constantly urged to attempt, if not impossibilities, at least what was exceedingly hazardous.

It was expected by the President, the Secretary of War, and Congress, that he would hasten his preparations, and advance upon the enemy, as he had over one hundred thousand men; and he made grand promises and gave assurances that he would march speedily upon Richmond. But he did not march. Delay succeeded delay, under various pretences, to the disappointment of the country, and the indignation of the responsible government. It was not till April, 1862, after five months of inaction, that he was ready to move upon Richmond, and then not according to pre-arranged plans, but by a longer route, by the way of Fortress Monroe, up the Peninsula between the York and James rivers, and not directly across Virginia by Manassas Junction, which had been evacuated in view of his superior forces,–the largest army theretofore seen on this continent.

It is not for me, utterly ignorant of military matters, to make any criticism of the plan of operations, in which the President and McClellan were at issue, or to censure the general in command for the long delay, against the expostulations of the Executive and of Congress. He maintained that his army was not sufficiently drilled, or large enough for an immediate advance, that the Confederate forces were greater than his own, and were posted in impregnable positions. He was always calling for reinforcements, until his army comprised over two hundred thousand men, and when at last imperatively commanded to move, some-whither,–at any rate to move,–he left Washington not sufficiently defended, which necessitated the withdrawal of McDowell’s corps from him to secure the safety of the capital. Without enumerating or describing the terrible battles on the Peninsula, and the “change of base,” which practically was a retreat, and virtually the confession of failure, it may be said in defence or palliation of McClellan that it afterwards took Grant, with still greater forces, and when the Confederates were weakened and demoralized, a year to do what McClellan was expected to do in three months.

The war had now been going on for more than a year, without any decisive results so far as the Army of the Potomac was concerned, but on the contrary with great disasters and bitter humiliations. The most prodigious efforts had been made by the Union troops without success, and thus far the Confederates had the best of it, and were filled with triumph. As yet no Union generals could be compared with Lee, or Johnston, or Longstreet, or Stonewall Jackson, while the men under their command were quite equal to the Northern soldiers in bravery and discipline.

The times were dark and gloomy at the North, and especially so to the President, as commander-in-chief of the army and navy, after all the energies he put forth in the general direction of affairs. He was maligned and misrepresented and ridiculed; yet he opened not his mouth, and kept his soul in patience,–magnanimous, forbearing, and modest. In his manners and conduct, though intrusted with greater powers than any American before him had ever exercised, he showed no haughtiness, no resentments, no disdain, but was accessible to everybody who had any claim on his time, and was as simple and courteous as he had been in a private station. But what anxieties, what silent grief, what a burden, had he to bear! And here was his greatness, which endeared him to the American heart,–that he usurped no authority, offended no one, and claimed nothing, when most men, armed as he was with almost unlimited authority, would have been reserved, arrogant, and dictatorial. He did not even assume the cold dignity which Washington felt it necessary to put on, but shook hands, told stories, and uttered jokes, as if he were without office on the prairies of Illinois; yet all the while resolute in purpose and invincible in spirit,–an impersonation of logical intellect before which everybody succumbed, as firm, when he saw his way clear, as Bismarck himself.

His tact in managing men showed his native shrewdness and kindliness, as well as the value of all his early training in the arts of the politician. Always ready to listen, and to give men free chance to relieve their minds in talk, he never directly antagonized their opinions, but, deftly embodying an argument in an apt joke or story, would manage to switch them off from their track to his own without their exactly perceiving the process. His innate courtesy often made him seem uncertain of his ground, but he probably had his own way quite as frequently as Andrew Jackson, and without that irascible old fighter’s friction.

But darker days were yet to come, and more perplexing duties had yet to be discharged. The President was obliged to retire McClellan from his command when, in August, 1862, that general’s procrastination could no longer be endured. McClellan had made no fatal blunders, was endeared to his men, and when it was obvious that he could not take Richmond, although within four miles of it at one time, he had made a successful and masterly retreat to Harrison’s Landing; yet the campaign against the Confederate capital had been a failure, as many believed, by reason of unnecessary delays on the part of the commander, and the President had to take the responsibility of sustaining or removing him. He chose the latter.

What general would Lincoln select to succeed McClellan? He chose General John Pope, but not with the powers which had been conferred on McClellan. Pope had been graduated at West Point in 1842, had served with distinction in the Mexican War, and had also done good service in the West. But it was his misfortune at this time to lose the second battle of Bull Run, or Manassas, when there was no necessity of lighting. He himself attributed his disaster to the inaction and disobedience of General Porter, who was cashiered for it,–a verdict which was reversed by a careful military inquiry after the war. Pope’s defeat was followed, although against the advice of the cabinet, by the restoration of McClellan, since Washington was again in danger. After he had put the capital in safety, McClellan advanced slowly against Lee, who had crossed the Potomac into Maryland with designs on Pennsylvania. He made his usual complaint of inadequate forces, and exaggerated the forces of the enemy. He won, however, the battle of Antietam,–for, although the Confederates afterwards claimed that it was a drawn battle, they immediately retired,–but even then failed to pursue his advantage, and allowed Lee to recross the Potomac and escape, to the deep disgust of everybody and the grief of Lincoln. Encouraged by McClellan’s continued inaction, Lee sent his cavalry under Stuart, who with two thousand men encircled the Federal army, and made a raid into Pennsylvania, gathering supplies, and retired again into Virginia, unhindered and unharmed. The President now deprived McClellan again of his command, and that general’s military career ended. He retired to private life, emerging again only as an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for the presidency against Lincoln in 1864.

It was a difficult matter for Lincoln to decide upon a new general to command the Army of the Potomac. He made choice of Ambrose E. Burnside, the next in rank,–a man of pleasing address and a gallant soldier, but not of sufficient abilities for the task imposed upon him. The result was the greatest military blunder of the whole war. With the idea of advancing directly upon Richmond through Fredericksburg, Burnside made the sad error of attacking equal forces strongly intrenched on the Fredericksburg Heights, while he advanced from the valley of the Rappahannock below, crossing the river under a plunging fire, and attacking the enemy on the hill. It was a dismal slaughter, but Burnside magnanimously took the whole blame upon himself, and was not disgraced, although removed from his command. He did good service afterwards as a corps-commander.

It was soon after Burnside’s unfortunate failure at Fredericksburg, perhaps the gloomiest period of the war, when military reverses saddened the whole North, and dissensions in the cabinet itself added to the embarrassments of the President, that Lincoln performed the most momentous act of his life, and probably the most important act of the whole war, in his final proclamation emancipating the slaves, and utilizing them in the Union service, as a military necessity.

Ever since the beginning of hostilities had this act been urged upon the President by the antislavery men of the North,–a body growing more intense and larger in numbers as the war advanced. But Lincoln remained steady to his original purpose of saving the Union,—whether with or without slavery. Naturally, and always opposed to slavery, he did not believe that he had any right to indulge his private feeling in violation of the Constitutional limitations of his civil power, unless, as he said, “measures otherwise unconstitutional might become lawful by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the Constitution through the preservation of the nation.”

Thus when in 1861 Frémont in Missouri proclaimed emancipation to the slaves of persistent rebels, although this was hailed with delight by vast numbers at the North, the President countermanded it as not yet an indispensable necessity. In March, 1862, he approved Acts of Congress legalizing General B.F. Butler’s shrewd device of declaring all slaves of rebels in arms as “contraband of war,” and thus, when they came within the army lines, to be freed and used by the Northern armies. In March, May, and July, 1862, he made earnest appeals to the Border States to favor compensated emancipation, because he foresaw that military emancipation would become necessary before long. When Lee was in Maryland and Pennsylvania, he felt that the time had arrived, and awaited only some marked military success, so that the measure should seem a mightier blow to the rebels and not a cry for help. And this was a necessary condition, for, while hundreds of thousands of Democrats had joined the armies and had become Republicans for the war,–in fact, all the best generals and a large proportion of the soldiers of the North had been Democrats before the flag was fired on,–yet the Democratic politicians of the proslavery type were still alive and active throughout the North, doing all they could to discredit the national cause, and hinder the government; and Lincoln intuitively knew that this act must commend itself to the great mass of the Northern people, or it would be a colossal blunder.

Therefore, when Lee had been driven back, on September 22, 1862, the President issued a preliminary proclamation, stating that he should again recommend Congress to favor an Act tendering pecuniary aid to slaveholders in States not in rebellion, who would adopt immediate or gradual abolishment of slavery within their limits; but that on the first day of January, 1863, “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall be in rebellion against the United States, shall be thenceforward and forever free.” And accordingly,–in spite of Burnside’s dreadful disaster before Fredericksburg on December 13, unfavorable results in the fall elections throughout the North, much criticism of his course in the newly-assembled Congress, and the unpopular necessity of more men and more money to be drawn from the loyal States,–on January 1, 1863, the courageous leader sent forth his final and peremptory Decree of Emancipation. He issued it, “by virtue of the power in me vested as commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war-measure for suppressing said rebellion.”

Of course such an edict would have no immediate force in the remoter States controlled by the Confederate government, nor at the time did it produce any remarkable sensation except to arouse bitter animadversion at the North and renewed desperation of effort at the South; but it immediately began to reduce the workers on intrenchments and fortifications along the Confederate front and to increase those of the Federal forces, while soon also providing actual troops for the Union armies; and, since it was subsequently indorsed by all the States, through an amendment to the Constitution by which slavery was forever prohibited in the States and Territories of the United States, and in view of its immense consequences, the Emancipation Proclamation of Lincoln must be regarded as perhaps the culminating event in the war. It was his own act; and he accepted all the responsibilities. The abolition of slavery is therefore forever identified with the administration of Lincoln.

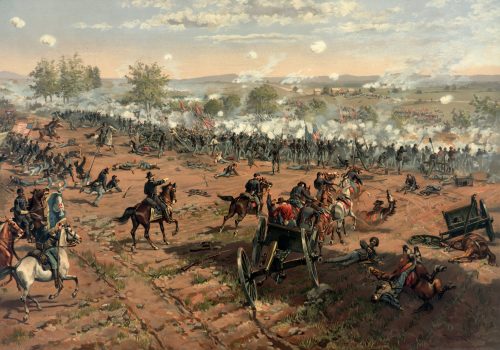

In the early part of 1863 Lincoln relieved Burnside of his command, and appointed General Joseph Hooker to succeed him. This officer had distinguished himself as a brilliant tactician; he was known as “fighting Joe;” but he was rash. He made a bold and successful march, crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers and advanced upon the enemy, but early in May, 1863, was defeated at Chancellorsville, in one of the bloodiest battles of the war. The Confederates were now exceedingly elated; and Lee, with a largely increased army of ninety thousand splendid fighting men, resolved on invading Pennsylvania in force. Evading Hooker, he passed through the Shenandoah Valley, and about the middle of June was in Pennsylvania before the Union forces could be gathered to oppose him. He took York and Carlisle and threatened Harrisburg. The invasion filled the North with dismay. Hooker, feeling his incompetency, and on bad terms with Halleck, the general-in-chief, asked to be relieved, and his request was at once granted.

General George C. Meade was appointed his successor on June 28. Striking due north with all speed, ably supported by a remarkable group of corps-commanders and the veteran Army of the Potomac handsomely reinforced and keenly eager to fight, Meade brought Lee to bay near the village of Gettysburg, and after three days of terrific fighting, in which the losses of the two armies aggregated over forty-five thousand men, on the 3d of July he defeated Lee’s army and turned it rapidly southward. This was the most decisive battle of the war, and the most bloody, finally lost by Lee through his making the same mistake that Burnside did at Fredericksburg, in attacking equal forces intrenched on a hill. Nothing was left to Lee but retreat across the Potomac, and Meade–an able but not a great captain–made the mistake that McClellan had made at Antietam in not following up his advantage, but allowing Lee to escape into Virginia.

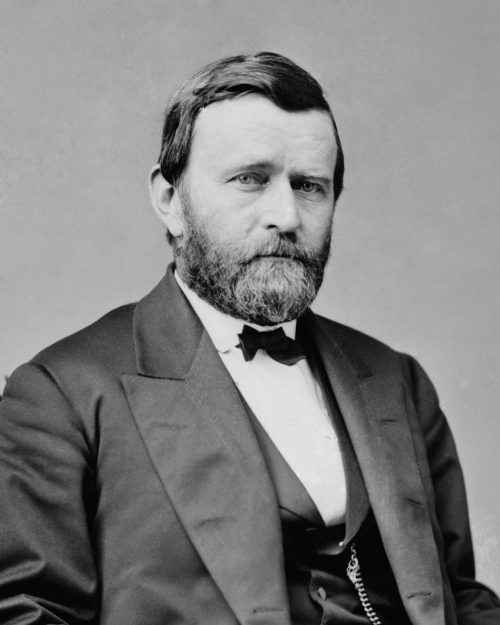

To cap the climax of Union success, on the 4th of July General Ulysses S. Grant, who had been operating against Vicksburg on the Mississippi during four months, captured that city, with thirty-two thousand prisoners, and a few days later Port Hudson with its garrison fell into his hands. The signal combination of victories filled the North with enthusiasm and the President with profoundest gratitude. It is true, Meade’s failure to follow and capture Lee was a bitter disappointment to Lincoln. The Confederate commander might have been compelled to surrender to a flushed and conquering army a third larger than his own, had Meade pursued and attacked him, and the war might perhaps virtually have ended. Yet Lee’s army was by no means routed, and was in dangerous mood, while Meade’s losses had been really larger than his; so that the Federal general’s caution does not lack military defenders. Nevertheless, he evidently was not the man that had been sought for.

More than two years had now elapsed since the Army of the Potomac had been organized by McClellan, and yet it was no nearer the end which the President, the war minister, the cabinet, and the generals had in view,–the capture of Richmond. Thus far, more than one hundred thousand men had been lost in the contest which the politicians had supposed was to be so brief. Not a single general had arisen at the East equal to the occasion. Only a few of the generals had seen important military service before the war, and not one had evinced remarkable abilities, although many had distinguished themselves for bravery and capacity to manage well an army corps. Each army commander had failed when great responsibilities had been imposed upon him. Not one came up to popular expectation. The great soldier must be “born” as well as “made.”

It must be observed that up to this time, in the autumn of 1863, the President had not only superintended the Army of the Potomac, but had borne the chief burden of the government and the war at large. Cabinet meetings, reports of generals, quarrels of generals, dissensions of political leaders, impertinence of editors, the premature pressure to emancipate slaves, Western campaigns, the affairs of the navy, and a thousand other things pressed upon his attention. It was his custom to follow the movements of every army with the map before him, and to be perfectly familiar with all the general, and many of the detailed, problems in every part of the vast field of the war. No man was ever more overworked. It may be a question how far he was wise in himself attending to so many details, and in giving directions to generals in high command, and sometimes against the advice of men more experienced in military matters. That is not for me to settle. He seemed to bear the government and all the armies on head and heart, as if the responsibility for everything was imposed upon him. What had been the history? In the East, two years clouded by disasters, mistakes, and national disappointments, with at last a breaking of the day,–and that, in the West.