Alexander Hamilton : American Constitution – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XI : American Founders by John Lord

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XI : American Founders

Preliminary Chapter : The American Idea

Benjamin Franklin : Diplomacy

George Washington : The American Revolution

Alexander Hamilton : American Constitution

John Adams : Constructive Statesmanship

Thomas Jefferson : Popular Sovereignty

John Marshall : The United States Supreme Court

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XI : American Founders

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Hamilton’s youth

Education

Precocity of intellect

State of political parties on the breaking out of the Revolutionary War

Their principles

Their great men

Hamilton leaves college for the army

Selected by Washington as his aide-de-camp at the age of nineteen

His early services to Washington

Suggestions to members of Congress

Trials and difficulties of the patriots

Demoralization of the country

Hamilton in active military service

Leaves the army; marries; studies law

Opening of his legal career

His peculiarities as a lawyer

Contrasted with Aaron Burr

Hamilton enters political life

Sees the necessity of a constitution

Convention at Annapolis

Convention at Philadelphia

The remarkable statesmen assembled

Discussion of the Convention

Great questions at issue

Constitution framed

Influence of Hamilton in its formation

Its ratification by the States

“The Federalist”

Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury

His transcendent financial genius

Restores the national credit

His various political services as statesman

The father of American industry

Protection

Federalists and Republicans

Hamilton’s political influence after his retirement

Resumes the law

His quarrel with Burr

His duel

His death

Burr’s character and crime

Hamilton’s services

His lasting influence

Alexander Hamilton : American Constitution

A. D. 1757-1804.

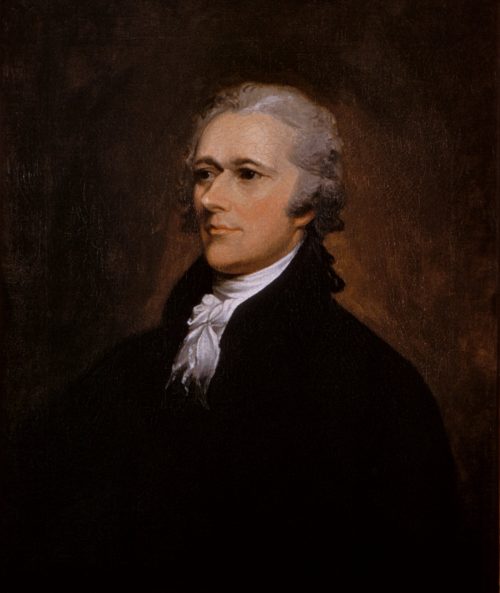

There is one man in the political history of the United States whom Daniel Webster regarded as his intellectual superior. And this man was Alexander Hamilton; not so great a lawyer or orator as Webster, not so broad and experienced a statesman, but a more original genius, who gave shape to existing political institutions. And he rendered transcendent services at a great crisis of American history, and died, with no decline of popularity, in the prime of his life, like Canning in England, with a brilliant future before him. He was one of those fixed stars which will forever blaze in the firmament of American lights, like Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson; and the more his works are critically examined, the brighter does his genius appear. No matter how great this country is destined to be,–no matter what illustrious statesmen are destined to arise, and work in a larger sphere with the eyes of the world upon them,–Alexander Hamilton will be remembered and will be famous for laying one of the corner-stones in the foundation of the American structure.

He was not born on American soil, but on the small West India Island of Nevis. His father was a broken-down Scotch merchant, and his mother was a bright and gifted French lady, of Huguenot descent. The Scotch and French blood blended, is a good mixture in a country made up of all the European nations. But Hamilton, if not an American by birth, was American in his education and sympathies and surroundings, and ultimately married into a distinguished American family of Dutch descent. At the age of twelve he was placed in the counting-house of a wealthy American merchant, where his marked ability made him friends, and he was sent to the United States to be educated. As a boy he was precocious, like Cicero and Bacon; and the boy was father of the man, since politics formed one of his earliest studies. Such a precocious politician was he while a student in King’s College, now Columbia, in New York, that at the age of seventeen he entered into all the controversies of the day, and wrote essays which, replying to pamphlets attacking Congress over the signature of “A Westchester Farmer,” were attributed to John Jay and Governor Livingston. As a college boy he took part in public political discussions on those great questions which employed the genius of Burke, and occupied the attention of the leading men of America.

This was at the period when the colonies had not actually rebelled, but when they meditated resistance,–during the years between 1773 and 1776, when the whole country was agitated by political tracts, indignation meetings, patriotic sermons, and preparations for military struggle. Hitherto the colonies had not been oppressed; they had most of the rights and privileges they desired; but they feared that their liberties–so precious to them, and which they had virtually enjoyed from their earliest settlements–were in danger of being wrested away. And their fears were succeeded by indignation when the Coercion Act was passed by the English parliament, and when it was resolved to tax them without their consent, and without a representation of their interests. Nor did they desire war, nor even, at first, entire separation from the Mother Country; but they were ready to accept war rather than to submit to injustice, or any curtailment of their liberties. They had always enjoyed self-government in such vital matters as schools, municipal and local laws, taxes, colonial judges, and unrestricted town-meetings. These privileges the Americans resolved at all hazard to keep: some, because they had been accustomed to them all their days; others, from the abstract idea of freedom which Rousseau had inculcated with so much eloquence, which fascinated such men as Franklin and Jefferson; and others again, from the deep conviction that the colonies were strong enough to cope successfully with any forces that England could then command, should coercion be attempted,–to which latter class Washington, Pinckney, and Jay belonged; men of aristocratic sympathies, but intensely American. It was no democratic struggle to enlarge the franchise, and realize Rousseau’s idea of fraternity and equality,–an idea of blended socialism, infidelity, and discontent,–which united the colonies in resistance; but a broad, noble, patriotic desire, first, to conserve the rights of free English colonists, and finally to make America independent of all foreign forces, combined with a lofty faith in their own resources for success, however desperate the struggle might be.

All parties now wanted independence, to possess a country of their own, free of English shackles. They got tired of signing petitions, of being mere colonists. So they sent delegates to Philadelphia to deliberate on their difficulties and aspirations; and on July 4, 1776, these delegates issued the Declaration of Independence, penned by Jefferson, one of the noblest documents ever written by the hand of man, the Magna Charta of American liberties, in which are asserted the great rights of mankind,–that all men have the right to seek happiness in their own way, and are entitled to the fruit of their labors; and that the people are the source of power, and belong to themselves, and not to kings, or nobles, or priests.

In signing this document the Revolutionary patriots knew that it meant war; and soon the struggle came,–one of the inevitable and foreordained events of history,–when Hamilton was still a college student. He was eighteen when the battle of Lexington was fought; and he lost no time in joining the volunteers. Dearborn and Stark from New Hampshire, Putnam and Arnold from Connecticut, and Greene from Rhode Island, all now resolved on independence, “liberty or death.” Hamilton left his college walls to join a volunteer regiment of artillery, of which he soon became captain, from his knowledge of military science which he had been studying in anticipation of the contest. In this capacity he was engaged in the battle of White Plains, the passage of the Raritan, and the battles at Princeton and Trenton.

When the army encamped at Morristown, in the gloomy winter of 1776-1777, his great abilities having been detected by the commander-in-chief, he was placed upon Washington’s staff, as aide-de-camp with the rank of lieutenant-colonel,–a great honor for a boy of nineteen. Yet he was not thus honored and promoted on account of remarkable military abilities, although, had he continued in active service, he would probably have distinguished himself as a general, for he had courage, energy, and decision; but he was selected by Washington on account of his marvellous intellectual powers. So, half-aide and half-secretary, he became at once the confidential adviser of the General, and was employed by him not only in his multitudinous correspondence, but in difficult negotiations, and in those delicate duties which required discretion and tact. He had those qualities which secured confidence,–integrity, diligence, fidelity, and a premature wisdom. He had brains and all those resources which would make him useful to his country. Many there were who could fight as well as he, but there were few who had those high qualities on which the success of a campaign depended. Thus he was sent to the camp of General Gates at Albany to demand the division of his forces and the reinforcement of the commander-in-chief, which Gates was very unwilling to accede to, for the capture of Burgoyne had turned his head. He was then the most popular officer of the army, and even aspired to the chief command. So he was inclined to evade the orders of his superior, under the plea of military necessity. It required great tact in a young man to persuade an ambitious general to diminish his own authority; but Hamilton was successful in his mission, and won the admiration of Washington for his adroit management. He was also very useful in the most critical period of the war in ferreting out conspiracies, cabala, and intrigues; for such there were, even against Washington, whose transcendent wisdom and patriotism were not then appreciated as they were afterwards.

The military services of Hamilton were concealed from the common eye, and lay chiefly in his sage counsels; for, young as he was, he had more intellect and sagacity than any man in the army. It was Hamilton who urged decisive measures in that campaign which was nearly blasted by the egotism and disobedience of Lee. It was Hamilton who was sent to the French admiral to devise a co-operation of forces, and to the headquarters of the English to negotiate for an exchange of prisoners. It was Hamilton who dissuaded Washington from seizing the person of Sir Harry Clinton, the English commander in New York, when he had the opportunity. “Have you considered the consequences of seizing the General?” said the aide. “What would these be?” inquired Washington. “Why,” replied Hamilton, “we should lose more than we should gain; since we perfectly understand his plans, and by taking them off, we should make way for an abler man, whose dispositions we have yet to learn.” Such was the astuteness which Hamilton early displayed, so that he really rendered great military services, without commanding on the field.

When quite a young man he was incidentally of great use in suggesting to influential members of Congress certain financial measures which were the germ of that fiscal policy which afterwards made him immortal as Secretary of the Treasury; for it was in finance that his genius shone out with the brightest lustre. It was while he was the aid and secretary of Washington that he also unfolded, in a letter to Judge Duane, those principles of government which were afterwards developed in “The Federalist.” He had “already formed comprehensive opinions on the situation and wants of the infant States, and had wrought out for himself a political system far in advance of the conceptions of his contemporaries.” It was by his opinions on the necessities and wants of the country, and the way to meet them, that his extraordinary genius was not only seen, but was made useful to those in power. His brain was too active and prolific to be confined to the details of military service; he entered into a discussion of all those great questions which formed the early constitutional history of the United States,–all the more remarkable because he was so young. In fact he never was a boy; he was a man before he was seventeen. His ability was surpassed only by his precocity. No man saw the evils of the day so clearly as he, or suggested such wise remedies as he did when he was in the family of Washington.

We are apt to suppose that it was all plain sailing after the colonies had declared their independence, and their armies were marshalled under the greatest man–certainly the wisest and best–in the history of America and of the eighteenth century. But the difficulties were appalling even to the stoutest heart. In less than two years after the battle of Bunker Hill popular enthusiasm had almost fled, although the leaders never lost hope of ultimate success. The characters of the leading generals were maligned, even that of the general-in-chief; trade and all industries were paralyzed; the credit of the States was at the lowest ebb; there were universal discontents; there were unforeseen difficulties which had never been anticipated; Congress was nearly powerless, a sort of advisory board rather than a legislature; the States were jealous of Congress and of each other; there was a general demoralization; there was really no central power strong enough to enforce the most excellent measures; the people were poor; demagogues sowed suspicion and distrust; labor was difficult to procure; the agricultural population was decimated; there was no commerce; people lived on salted meats, dried fish, baked beans, and brown bread; all foreign commodities were fabulously dear; there was universal hardship and distress; and all these evils were endured amid foreign contempt and political disintegration,–a sort of moral chaos difficult to conceive. It was amid these evils that our Revolutionary fathers toiled and suffered. It was against these that Hamilton brought his great genius to bear.

At the age of twenty-three, after having been four years in the family of Washington as his adviser rather than subordinate, Hamilton, doubtless ambitious, and perhaps elated by a sense of his own importance, testily took offence at a hasty rebuke on the part of the General and resigned his situation. Loath was Washington to part with such a man from his household. But Hamilton was determined, and tardily he obtained a battalion, with the brevet rank of general, and distinguished himself in those engagements which preceded the capture of Lord Cornwallis; and on the surrender of this general,–feeling that the war was virtually ended,–he withdrew altogether from the army, and began the study of law at Albany. He had already married the daughter of General Schuyler, and thus formed an alliance with a powerful family. After six months of study he was admitted to the Bar, and soon removed to New York, which then contained but twenty-five thousand inhabitants.

His legal career was opened, like that of Cicero and Erskine, by a difficult case which attracted great attention and brought him into notice. In this case he rendered a political service as well as earned a legal fame. An action was brought by a poor woman, impoverished by the war, against a wealthy British merchant, to recover damages for the use of a house he enjoyed when the city was occupied by the enemy. The action was founded on a recent statute of the State of New York, which authorized proceedings for trespass by persons who had been driven from their homes by the invasion of the British. The plaintiff therefore had the laws of New York on her side, as well as popular sympathies; and her claim was ably supported by the attorney-general. But it involved a grave constitutional question, and conflicted with the articles of peace which the Confederation had made with England; for in the treaty with Great Britain an amnesty had been agreed to for all acts done during the war by military orders. The interests of the plaintiff were overlooked in the great question whether the authority of Congress and the law of nations, or the law of a State legislature, should have the ascendency. In other words, Congress and the State of New York were in conflict as to which should be paramount,–the law of Congress, or the law of a sovereign State,–in a matter which affected a national treaty. If the treaty were violated, new complications would arise with England, and the authority of Congress be treated with contempt. Hamilton grappled with the subject in the most comprehensive manner,–like a statesman rather than a lawyer,–made a magnificent argument in favor of the general government, and gained his case; although it would seem that natural justice was in favor of the poor woman, deprived of the use of her house by a wealthy alien, during the war. He rendered a service to centralized authority, to the power of Congress. It was the incipient contest between Federal and State authority. It was enlightened reason and patriotism gaining a victory over popular passions, over the assumptions of a State. It defined the respective rights of a State and of the Nation collectively. It was one of those cases which settled the great constitutional question that the authority of the Nation was greater than that of any State which composed it, in matters where Congress had a recognized jurisdiction.

It was about this time that Hamilton was brought in legal conflict with another young man of great abilities, ambition, and popularity; and this man was Aaron Burr, a grandson of Jonathan Edwards. Like Hamilton, he had gained great distinction in the war, and was one of the rising young men of the country. He was superior to Hamilton in personal popularity and bewitching conversation; his equal in grace of manner, in forensic eloquence and legal reputation, but his inferior in comprehensive intellect and force of character. Hamilton dwelt in the region of great ideas and principles; Burr loved to resort to legal technicalities, sophistries, and the dexterous use of dialectical weapons. In arguing a case he would descend to every form of annoyance and interruption, by quibbles, notices, and appeals. Both lawyers were rapid, logical, compact, and eloquent. Both seized the strong points of a case, like Mason and Webster. Hamilton was earnest and profound, and soared to elemental principles. Burr was acute, adroit, and appealed to passions. Both admired each other’s talents and crossed each other’s tracks,–rivals at the Bar and in political aspirations. The legal career of both was eclipsed by their political labors. The lawyer, in Hamilton’s case, was lost in the statesman, and in Burr’s in the politician. And how wide the distinction between a statesman and a politician! To be a great statesman a man must be conversant with history, finance, and science; he must know everything, like Gladstone, and he must have at heart the great interests of a nation; he must be a man of experience and wisdom and reason; he must be both enlightened and patriotic, merging his own personal ambition in the good of his country,–an oracle and sage whose utterances are received with attention and respect. To be a statesman demands the highest maturity of reason, far-reaching views, and the power of taking in the interests of a whole country rather than of a section. But to be a successful politician a man may be ignorant, narrow, and selfish; most probably he will be artful, dissembling, going in for the winning side, shaking hands with everybody, profuse in promises, bland, affable, ready to do anything for anybody, and seeking the interests and flattering the prejudices of his own constituency, indifferent to the great questions on which the welfare of a nation rests, if only his own private interests be advanced. All politicians are not so small and contemptible; many are honest, as far as they can see, but can see only petty details, and not broad effects. Mere politicians,–observe, I qualify what I say,–mere politicians resemble statesmen, intellectually, as pedants resemble scholars of large culture, comprehensive intellects, and varied knowledge; they will consider a date, or a name, or a comma, of more importance than the great universe, which no one can ever fully and accurately explore.

I have given but a short notice of Hamilton as a lawyer, because his services as a statesman are of so much greater importance, especially to the student of history. His sphere became greatly enlarged when he entered into those public questions on which the political destiny of a nation rests. He was called to give a direction to the policy of the young government that had arisen out of the storms of revolution,–a policy which must be carried out when the nation should become powerful and draw upon itself the eyes of the civilized world. “Just as the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined.” It was the privilege and glory of Hamilton to be one of the most influential of all the men of his day in bending the twig which has now become so great a tree. We can see his hand in the distinctive features of our Constitution, and especially in that financial policy which extricated the nation from the poverty and embarrassments bequeathed by the war, and which, on the whole, has been the policy of the Government from his day to ours. Greater statesmen may arise than he, but no future statesman will ever be able to shape a national policy as he has done. He is one of the great fathers of the Republic, and was as efficient in founding a government and a financial policy, as Saint Augustine was in giving shape to the doctrines of the Church in his age, and in mediaeval ages. Hamilton was therefore a benefactor to the State, as Augustine was to the Church.

But before Hamilton could be of signal service to the country as an organizer and legislator, it was necessary to have a national government which the country would accept, and which would be lasting and efficient. There was a political chaos for years after the war. Congress had no generally recognized authority; it was merely a board of delegates, whose decisions were disregarded, representing a league of States, not an independent authority. There was no chief executive officer, no court of national judges, no defined legislature. We were a league of emancipated colonies drifting into anarchy. There was really no central government; only an autonomy of States like the ancient Grecian republics, and the lesser States were jealous of the greater. The great questions pertaining to slavery were unsettled,–how far it should extend, and how far it could be interfered with. We had ships and commerce, but no commercial treaties with other nations. We imported goods and merchandise, but there were no laws of tariff or of revenue. If one State came into collision with another State, there was no tribunal to settle the difficulty. No particular industries were protected. Of all things the most needed was a national government superior to State governments, taking into its own hands exclusively the army and navy, tariffs, revenues, the post-office, the regulation of commerce, and intercourse with foreign States. Oh, what times those were! What need of statesmanship and patriotism and wisdom! I have alluded to various evils of the day. I will not repeat them. Why, our condition at the end of the War of the Rebellion, when we had a national debt of three thousand millions, and general derangement and demoralization, was an Elysium compared with that of our fathers at the close of the Revolutionary War,–no central power, no constitution, no government, with poverty, agricultural distress, and uncertainty, and the prostration of all business; no national credit, no national éclat,–a mass of rude, unconnected, and anarchic forces threatening to engulf us in worse evils than those from which we had fled.

The thinking and sober men of the country were at last aroused, and the conviction became general that the Confederacy was unable to cope with the difficulties which arose on every side. So, through the influence of Hamilton, a convention of five States assembled at Annapolis to provide a remedy for the public evils. But it did not fully represent the varied opinions and interests of the whole country. All it could do was to prepare the way for a general convention of States; and twelve States sent delegates to Philadelphia, who met in the year 1787. The great public career of Hamilton began as a delegate from the State of New York to this illustrious assembly. He was not the most distinguished member, for he was still a young man; nor the most popular, for he had too much respect for the British constitution, and was too aristocratic in his sympathies, and perhaps in his manners, to be a favorite. But he was probably the ablest man of the convention, the most original and creative in his genius, the most comprehensive and far-seeing in his views,–a man who inspired confidence and respect for his integrity and patriotism, combining intellectual with moral force. He would have been a great man in any age or country, or in any legislative assembly,–a man who had great influence over superior minds, as he had over that of Washington, whose confidence he had from first to last.

I am inclined to think that no such an assembly of statesmen has since been seen in this country as that which met to give a constitution to the American Republic. Of course, I cannot enumerate all the distinguished men. They were all distinguished,–men of experience, patriotism, and enlightened minds. There were fifty-four of these illustrious men,–the picked men of the land, of whom the nation was proud. Franklin, now in his eightieth year, was the Nestor of the assembly, covered with honors from home and abroad for his science and his political experience and sagacity,–a man who received more flattering attentions in France than any American who ever visited it; one of the great savants of the age, dignified, affable, courteous, whom everybody admired and honored. Washington, too, was there,–the Ulysses of the war, brave in battle and wise in council, of transcendent dignity of character, whose influence was patriarchal, the synonym of moral greatness, to be revered through all ages and countries; a truly immortal man whose fame has been steadily increasing. Adams, Jefferson, and Jay, three very great lights, were absent on missions to Europe; but Rufus King, Roger Sherman, Oliver Ellsworth, Livingston, Dickinson, Rutledge, Randolph, Pinckney, Madison, were men of great ability and reputation, independent in their views, but all disposed to unite in the common good. Some had been delegates to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765; some, members of the Continental Congress of 1774; some, signers of the Declaration of Independence. There were no political partisans then, as we now understand the word, for the division lines of parties were not then drawn. All were animated with the desire of conciliation and union. All felt the necessity of concessions. They differed in their opinions as to State rights, representation, and slavery. Some were more democratic, and some more aristocratic than the majority, but all were united in maintaining the independence of the country and in distrust of monarchies.

It is impossible within my narrow limits to describe the deliberations of these patriots, until their work was consummated in the glorious Constitution which is our marvel and our pride. The discussions first turned on the respective powers to be exercised by the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of the proposed central government, and the duration of the terms of service. Hamilton’s views favored a more efficient executive than was popular with the States or delegates; but it cannot be doubted that his powerful arguments, and clear enunciation of fundamental principles of government had great weight with men more eager for truth than victory. There were animated discussions as to the ratio of representation, and the equality of States, which gave rise to the political parties which first divided the nation, and which were allied with those serious questions pertaining to State rights which gave rise, in part, to our late war. But the root of the dissensions, and the subject of most animated debates, was slavery,–that awful curse and difficult question, which was not settled until the sword finally cut that Gordian knot. But so far as compromises could settle the question, they were made in the spirit of patriotism,–not on principles of abstract justice, but of expediency and common-sense. It was evident from the first that there could be no federal, united government, no nation, only a league of States, unless compromises were made in reference to slavery, whose evils were as apparent then as they were afterwards. For the sake of nationality and union and peace, slavery was tolerated by the Constitution. To some this may appear to have been a grave error, but to the makers of the Constitution it seemed to be a less evil to tolerate slavery than have no Constitution at all, which would unite all the States. Harmony and national unity seemed to be the paramount consideration.

So a compromise was made. We are apt to forget how great institutions are often based on compromise,–not a mean and craven sentiment, as some think, but a spirit of conciliation and magnanimity, without which there can be no union or stability. Take the English Church, which has survived the revolutions of human thought for three centuries, which has been a great bulwark against infidelity, and has proved itself to be dear to the heart of the nation, and the source of boundless blessings and proud recollections,–it was a compromise, half-way indeed between Rome and Geneva, but nevertheless a great and beneficent organization on the whole. Take the English constitution itself, one of the grandest triumphs of human reason and experience,–it was only gradually formed by a series of bloodless concessions. Take the Roman constitution, under which the whole civilized world was brought into allegiance,–it was a series of concessions granted by the aristocratic classes. Most revolutions and wars end in compromise after the means of fighting are expended. Most governments are based on expediency rather than abstract principles. The actions of governments are necessarily expedients,–the wisest policy in view of all the circumstances. Even such an uncompromising logician as Saint Paul accepted some customs which we think were antagonistic to the spirit of his general doctrines. He was a great temperance man, but recommended a little wine to Timothy for the stomach’s sake. And Moses, too, the great founder of the Jewish polity, permitted polygamy because of the hardness of men’s hearts. So the fathers of the Constitution preferred a constitution with slavery to no constitution at all. Had each of those illustrious men persisted in his own views, we should have had only an autonomy of States instead of the glorious Union, which in spite of storms stands unshaken to-day.

I cannot dwell on those protracted debates, which lasted four months, or on the minor questions which demanded attention,–all centering in the great question whether the government should be federative or national. But the ablest debater of the convention was Hamilton, and his speeches were impressive and convincing. He endeavored to impress upon the minds of the members that liberty was found neither in the rule of a few aristocrats, nor in extreme democracy; that democracies had proved more short-lived than aristocracies, as illustrated in Greece, Rome, and England. He showed that extreme democracies, especially in cities, would be governed by demagogues; that universal suffrage was a dangerous experiment when the people had neither intelligence nor virtue; that no government could last which was not just and enlightened; that all governments should be administered by men of experience and integrity; that any central government should have complete control over commerce, tariffs, revenues, post-offices, patents, foreign relations, the army and navy, peace or war; and that in all these functions of national interest the central government should be independent of State legislatures, so that the State and National legislatures should not clash. Many of his views were not adopted, but it is remarkable that the subsequent changes and modifications of the Constitution have been in the direction of his policy; that wars and great necessities have gradually brought about what he advocated with so much calmness and wisdom. Guizot asserts that “he must ever be classed among the men who have best understood the vital principles and elemental conditions of government; and that there is not in the Constitution of the United States an element of order, or force, or duration which he did not powerfully contribute to secure.” This is the tribute of that great and learned statesman and historian to the genius and services of Hamilton. What an exalted praise! To be the maker of a constitution requires the highest maturity of reason. It was the peculiar glory of Moses,–the ablest man ever born among the Jews, and the greatest benefactor his nation ever had. How much prouder the fame of a beneficent and enlightened legislator than that of a conqueror! The code which Napoleon gave to France partially rescues his name from the infamy that his injuries inflicted on mankind. Who are the greatest men of the present day, and the most beneficent? Such men as Gladstone and Bright, who are seeking by wise legislation to remove or meliorate the evils of centuries of injustice. Who have earned the proudest national fame in the history of America since the Constitution was made? Such men as Webster, Clay, Seward, Sumner, who devoted their genius to the elucidation of fundamental principles of government and political economy. The sphere of a great lawyer may bring more personal gains, but it is comparatively narrow to that of a legislator who originates important measures for the relief or prosperity of a whole country.

The Constitution when completed was not altogether such as Hamilton would have made, but he accepted it cordially as the best which could be had. It was not perfect, but probably the best ever devised by human genius, with its checks and balances, “like one of those rocking-stones reared by the Druids,” as Winthrop beautifully said, “which the finger of a child may vibrate to its centre, yet which the might of an army cannot move from its place.”

The next thing to be done was to secure its ratification by the several States,–a more difficult thing than at first sight would be supposed; for the State legislatures were mainly composed of mere politicians, without experience or broad views, and animated by popular passions. So the States were tardy in accepting it, especially the larger ones, like Virginia, New York, and Massachusetts. And it may reasonably be doubted whether it would have been accepted at all, had it not been for the able papers which Hamilton, Madison, and Jay wrote and published in a leading New York paper,–essays which go under the name of “The Federalist,” long a text-book in our colleges, and which is the best interpreter of the Constitution itself. It is everywhere quoted; and if those able papers may have been surpassed in eloquence by some of the speeches of our political orators, they have never been equalled in calm reasoning. They appealed to the intelligence of the age,–an age which loved to read Butler’s “Analogy,” and Edwards “On the Will;” an age not yet engrossed in business and pleasure, when people had time to ponder on what is profound and lofty; an age not so brilliant as our own in mechanical inventions and scientific researches, but more contemplative, and more impressible by grand sentiments. I do not say that the former times were better than these, as old men have talked for two thousand years, for those times were hard, and the struggles of life were great,–without facilities of travel, without luxuries, without even comforts, as they seem to us; but there was doubtless then a loftier spiritual life, and fewer distractions in the pursuit of solid knowledge; people then could live in the country all the year round without complaint, or that restless craving for novelties which demoralizes and undermines the moral health. Hamilton wrote sixty-three of the eighty-five (more than half) of these celebrated papers which had a great influence on public opinion,–clear, logical, concise, masterly in statement, and in the elucidation of fundamental principles of government. Probably no series of political essays has done so much to mould the opinions of American statesmen as those of “The Federalist,”–a thesaurus of political wisdom, as much admired in Europe as in America. It was translated into most of the European languages, and in France placed side by side with Montesquieu’s “Spirit of Laws” in genius and ability. It was not written for money or fame, but from patriotism, to enlighten the minds of the people, and prepare them for the reception of the Constitution.

In this great work Hamilton rendered a mighty service to his country. Nothing but the conclusive arguments which he made, assisted by Jay and Madison, aroused the people fully to a sense of the danger attending an imperfect union of States. By the efforts of Hamilton outside the convention, more even than in the convention, the Constitution was finally adopted,–first by Delaware and last by Rhode Island, in 1790, and then only by one majority in the legislature. So difficult was the work of construction. We forget the obstacles and the anxieties and labors of our early statesmen, in the enjoyment of our present liberties.

But the public services of Hamilton do not end here. To him pre-eminently belongs the glory of restoring or creating our national credit, and relieving universal financial embarrassments. The Constitution was the work of many men. Our financial system was the work of one, who worked alone, as Michael Angelo worked on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

When Washington became President, he at once made choice of Hamilton as his Secretary of the Treasury, at the recommendation of Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolution, who not only acknowledged his own obligations to him, but declared that he was the only man in the United States who could settle the difficulty about the public debt. In finance, Hamilton, it is generally conceded, had an original and creative genius. “He smote the rock of the national resources,” said Webster, “and abundant streams of revenue gushed forth. He touched the dead corpse of the public credit, and it sprang upon its feet. The fabled birth of Minerva from the brain of Jupiter was hardly more sudden than the financial system of the United States as it burst from the conception of Alexander Hamilton.”

When he assumed the office of Secretary of the Treasury there were five forms of public indebtedness for which he was required to provide,–the foreign debt; debts of the Government to States; the army debt; the debt for supplies in the various departments during the war; and the old Continental issues. There was no question about the foreign debt. The assumption of the State debts incurred for the war was identical with the debts of the Union, since they were incurred for the same object. In fact, all the various obligations had to be discharged, and there was neither money nor credit. Hamilton proposed a foreign loan, to be raised in Europe; but the old financiers had sought foreign loans and failed. How was the new Congress likely to succeed any better? Only by creating confidence; making it certain that the interest of the loan would be paid, and paid in specie. In other words, they were to raise a revenue to pay this interest. This simple thing the old Congress had not thought of, or had neglected, or found impracticable. And how should the required revenue be raised? Direct taxation was odious and unreliable. Hamilton would raise it by duties on imports. But how was an impoverished country to raise money to pay the duties when there was no money? How was the dead corpse to be revived? He would develop the various industries of the nation, all in their infancy, by protecting them, so that the merchants and the manufacturers could compete with foreigners; so that foreign goods could be brought to our seaports in our own ships, and our own raw materials exchanged for articles we could not produce ourselves, and be subject to duties,–chiefly on articles of luxury, which some were rich enough to pay for. And he would offer inducements for foreigners to settle in the country, by the sale of public lands at a nominal sum,–men who had a little money, and not absolute paupers; men who could part with their superfluities for either goods manufactured or imported, and especially for some things they must have, on which light duties would be imposed, like tea and coffee; and heavy duties for things which the rich would have, like broadcloths, wines, brandies, silks, and carpets. Thus a revenue could be raised more than sufficient to pay the interest on the debt. He made this so clear by his luminous statements, going into all details, that confidence gradually was established both as to our ability and also our honesty; and money flowed in easily and plentifully from Europe, since foreigners felt certain that the interest on their loans would be paid.

Thus in all his demonstrations he appealed to common-sense, not theories. He took into consideration the necessities of his own country, not the interests of other countries. He would legislate for America, not universal humanity. The one great national necessity was protection, and this he made as clear as the light of the sun. “One of our errors,” said he, “is that of judging things by abstract calculations, which though geometrically true, are practically false.” It was clear that the Government must have a revenue, and that revenue could only be raised by direct or indirect taxation; and he preferred, under the circumstances of the country, indirect taxes, which the people did not feel, and were not compelled to pay unless they liked; for the poor were not compelled to buy foreign imports, but if they bought them they must pay a tax to government. And he based his calculations that people could afford to purchase foreign articles, of necessity and luxury, on the enormous resources of the country,–then undeveloped, indeed, but which would be developed by increasing settlements, increasing industries, and increasing exports; and his predictions were soon fulfilled. In a few years the debt disappeared altogether, or was felt to be no burden. The country grew rich as its industries were developed; and its industries were developed by protection.

I will not enter upon that unsettled question of political economy. There are two sides to it. What is adapted to the circumstances of one country may not be adapted to another; what will do for England may not do practically for Russia; and what may be adapted to the condition of a country at one period may not be adapted at another period. When a country has the monopoly of a certain manufacture, then that country can dispense with protection. Before manufactures were developed in England by the aid of steam and improved machinery, the principles of free-trade would not have been adopted by the nation. The landed interests of Great Britain required no protection forty years ago, since there was wheat enough raised in the country to supply demands. So the landed aristocracy accepted free-trade, because their interests were not jeopardized, and the interests of the manufacturers were greatly promoted. Now that the landed interests are in jeopardy from a diminished rental, they must either be protected, or the lands must be cut up into small patches and farms, as they are in France. Farmers must raise fruit and vegetables instead of wheat.

When Hamilton proposed protection for our infant manufactures, they never could have grown unless they had been assisted; we should have been utterly dependent on Europe. That is just what Europe would have liked. But he did not legislate for Europe, but for America. He considered its necessities, not abstract theories, nor even the interests of other nations. How hypocritical the cant in England about free-trade! There never was free-trade in that country, except in reference to some things it must have, and some things it could monopolize. Why did Parliament retain the duty on tobacco and wines and other things? Because England must have a revenue. Hamilton did the same. He would raise a revenue, just as Great Britain raises a revenue to-day, in spite of free-trade, by taxing certain imports. And if the manufactures of England to-day should be in danger of being swamped by foreign successful competition, the Government would change its policy, and protect the manufactures. Better protect them than allow them to perish, even at the expense of national pride.

But the manufactures of this country at the close of the Revolutionary War were too insignificant to expect much immediate advantage from protection. It was Hamilton’s policy chiefly to raise a revenue, and to raise it by duties on imports, as the simplest and easiest and surest way, when people were poor and money was scarce. Had he lived in these days, he might have modified his views, and raised revenue in other ways. But he labored for his time and circumstances. He took into consideration the best way to raise a revenue for his day; for this he must have, somehow or other, to secure confidence and credit. He was most eminently practical. He hated visionary ideas and abstract theories; he had no faith in them at all. You can push any theory, any abstract truth even, into absurdity, as the theologians of the Middle Ages carried out their doctrines to their logical sequence. You cannot settle the complicated relations of governments by deductions. At best you can only approximate to the truth by induction, by a due consideration of conflicting questions and issues and interests.

The next important measure of Hamilton was the recommendation of a National Bank, in order to facilitate the collection of the revenue. Here he encountered great opposition. Many politicians of the school of Jefferson were jealous of moneyed institutions, but Hamilton succeeded in having a hank established though not with so large a capital as he desired.

It need not he told that the various debates in Congress on the funding of the national debt, on tariffs, on the bank, and other financial measures, led to the formation of two great political parties, which divided the nation for more than twenty years,–parties of which Hamilton and Jefferson were the respective leaders. Madison now left the support of Hamilton, and joined hands with the party of Jefferson, which took the name of Republican, or Democratic-Republican. The Federal party, which Hamilton headed, had the support of Washington, Adams, Jay, Pinckney, and Morris. It was composed of the most memorable names of the Revolution and, it may be added, of the more wealthy, learned, and conservative classes: some would stigmatize it as being the most aristocratic. The colleges, the courts of law, and the fashionable churches were generally presided over by Federalists. Old gentlemen of social position and stable religious opinions belonged to this party. But ambitious young men, chafing under the restraints of consecrated respectability, popular politicians, or as we might almost say the demagogues, the progressive and restless people and liberal thinkers enamored of French philosophy and theories and abstractions, were inclined to be Republicans. There were exceptions, of course. I only speak in a general way; nor would I give the impression that there were not many distinguished, able, and patriotic men enlisted in the party of Jefferson, especially in the Southern States, in Pennsylvania, and New York. Jefferson himself was, next to Hamilton, the ablest statesman of the country,–upright, sincere, patriotic, contemplative; simple in taste, yet aristocratic in habits; a writer rather than an orator, ignorant of finance, but versed in history and general knowledge, devoted to State rights, and bitterly opposed to a strong central power. He hated titles, trappings of rank and of distinction, ostentatious dress, shoe-buckles, hair-powder, pig-tails, and everything English, while he loved France and the philosophy of liberal thinkers; not a religious man, but an honest and true man. And when he became President, on the breaking up of the Federal party, partly from the indiscretions of Adams and the intrigues of Burr, and hostility to the intellectual supremacy of Hamilton,–who was never truly popular, any more than Webster and Burke were, since intellectual arrogance and superiority are offensive to fortunate or ambitious nobodies,–Jefferson’s prudence and modesty kept him from meddling with the funded debt and from entangling alliances with the nation he admired. Jefferson was not sweeping in his removals from office, although he unfortunately inaugurated that fatal policy consummated by Jackson, which has since been the policy of the Government,–that spoils belong to victors. This policy has done more to demoralize the politics of the country than all other causes combined; yet it is now the aim of patriotic and enlightened men to destroy its power and re-introduce that of Washington and Hamilton, and of all nations of political experience. The civil-service reform is now one of the main questions and issues of American legislation; but so bitterly is it opposed by venal politicians that I fear it cannot be made fully operative until the country demands it as imperatively as the English did the passage of their Reform Bill. However, it has gained so much popular strength that both of the prominent political parties of the present time profess to favor it, and promise to make it effective.

It would be interesting to describe the animosities of the Federal and Republican parties, which have since never been equalled in bitterness and rancor and fierceness, but I have not time. I am old enough to remember them, until they passed away with the administration of General Jackson, when other questions arose. With the struggle for ascendency between these political parties, the public services of Hamilton closed. He resumed the practice of the law in New York, even before the close of Washington’s administration. He became the leader of the Bar, without making a fortune; for in those times lawyers did not know how to charge, any more than city doctors. I doubt if his income as a lawyer ever reached $10,000 a year; but he lived well, as most lawyers do, even if they die poor. His house was the centre of hospitalities, and thither resorted the best society of the city, as well as distinguished people from all parts of the country.

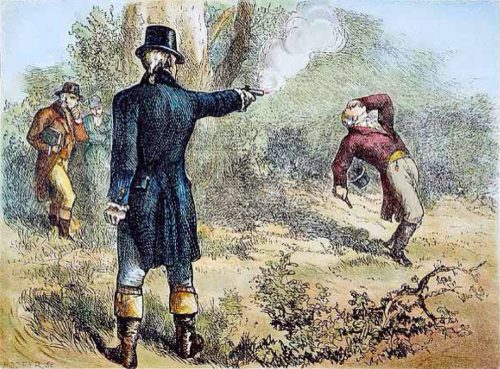

Nor did his political influence decline after he had parted with power. He was a rare exception to most public men after their official life is ended; and nothing so peculiarly marks a great man as the continuance of influence with the absence of power; for influence and power are distinct. Influence, in fact, never passes away, but power is ephemeral. Theologians, poets, philosophers, great writers, have influence and no power; railroad kings and bank presidents have power but not necessarily influence. Saint Augustine, in a little African town, had more influence than the bishop of Rome. Rousseau had no power, but he created the French Revolution. Socrates revolutionized Greek philosophy, but had not power enough to save his life from unjust accusations. What an influence a great editor wields in these times, yet how little power he has, unless he owns the journal he directs! What an influence was enjoyed by a wise and able clergyman in New England one hundred years ago, and which was impossible without force of character and great wisdom! Hamilton had wisdom and force of character, and therefore had great influence with his party after he retired from office. Most of our public men retire to utter obscurity when they have lost office, but Hamilton was as prominent in private life as in his official duties. He was the oracle of his party, a great political sage, whose utterances had the moral force of law. He never lost the leadership of his party, even when he retired from public life. His political influence lasted till he died. He had no rewards to give, no office to fill, but he still ruled like a chieftain. It was he who defeated by his quiet influence the political aspirations of Burr, when Burr was the most popular man in the country,–a great wire-puller, a prince of politicians, a great organizer of political forces, like Van Buren and Thurlow Weed,–whose eloquent conversation and fascinating manner few men could resist, to say nothing of women. But for Hamilton, he would in all probability have been President of the United States, at a time when individual genius and ability might not unreasonably aspire to that high office. He was the rival of Jefferson, and lost the election by only one vote, after the equality of candidates had thrown the election into the House of Representatives. Hamilton did not like Jefferson, but he preferred Jefferson to Burr, since he knew that the country would be safe under his guidance, and would not be safe with so unscrupulous a man as Burr. He distrusted and disliked Burr; not because he was his rival at the Bar,–for great rival lawyers may personally be good friends, like Brougham and Lyndhurst, like Mason and Webster,–but because his political integrity was not to be trusted; because he was a selfish and scheming politician, bent on personal advancement rather than the public good. And this hostility was returned with an unrelenting and savage fierceness, which culminated in deadly wrath when Burr found that Hamilton’s influence prevented his election as Governor of New York,–which office, it seems, he preferred to the Vice-presidency, which had dignity but no power. Burr wanted power rather than influence. In his bitter disappointment and remorseless rage, nothing would satisfy him but the blood of Hamilton. He picked a quarrel, and would accept neither apology nor reconciliation; he wanted revenge.

Hamilton knew he could not escape Burr’s vengeance; that he must fight the fatal duel, in obedience to that “code of honor” which had tyrannically bound gentlemen since the feudal ages, though unknown to Pagan Greece and Rome. There was no law or custom which would have warranted a challenge from Aeschines to Demosthenes, when the former was defeated in the forensic and oratorical contest and sent into banishment. But the necessity for Hamilton to fight his antagonist was such as he had not the moral power to resist, and that few other men in his circumstances would have resisted. In the eyes of public men there was no honorable way of escape. Life or death turned on his skill with the pistol; and he knew that Burr, here, was his superior. So he made his will, settled his affairs, and offered up his precious life; not to his country, not to a great cause, not for great ideas and interests, but to avoid the stigma of society,–a martyr to a feudal conventionality. Such a man ought not to have fought; he should have been above a wicked social law. But why expect perfection? Who has not infirmities, defects, and weaknesses? How few are beyond their age in its ideas; how few can resist the pressure of social despotism! Hamilton erred by our highest standard, but not when judged by the circumstances that surrounded him. The greatest living American died really by an assassin’s hand, since the murderer was animated with revenge and hatred. The greatest of our statesmen passed away in a miserable duel; yet ever to be venerated for his services and respected for his general character, for his integrity, patriotism, every gentlemanly quality,–brave, generous, frank, dignified, sincere, and affectionate in his domestic relations.

His death, on the 11th of July, 1804, at the early age of forty-seven,–the age when Bacon was made Lord Chancellor, the age when most public men are just beginning to achieve fame,–was justly and universally regarded as a murder; not by the hand of a fanatic or lunatic, but by the deliberately malicious hand of the Vice-President of the United States, and a most accomplished man. It was a cold, intended, and atrocious murder, which the pulpit and the press equally denounced in most unmeasured terms of reprobation, and with mingled grief and wrath. It created so profound an impression on the public mind that duelling as a custom could no longer stand so severe a rebuke, and it practically passed away,–at least at the North.

And public indignation pursued the murderer, though occupying the second highest political office in the country. He paid no insignificant penalty for his crime. He never anticipated such a retribution. He was obliged to flee; he became an exile and a wanderer in foreign lands,–poor, isolated, shunned. He was doomed to eternal ignominy; he never recovered even political power and influence; he did not receive even adequate patronage as a lawyer. He never again reigned in society, though he never lost his fascination as a talker. He was a ruined man, in spite of services and talents and social advantages; and no whitewashing can ever change the verdict of good men in this country. Aaron Burr fell,–like Lucifer, like a star from heaven,–and never can rise again in the esteem of his countrymen; no time can wipe away his disgrace. His is a blasted name, like that of Benedict Arnold. And here let me say, that great men, although they do not commit crimes, cannot escape the penalty of even defects and vices that some consider venial. No position however lofty, no services however great, no talents however brilliant, will enable a man to secure lasting popularity and influence when respect for his moral character is undermined; ultimately he will fall. He may have defects, he may have offensive peculiarities, and retain position and respect, for everybody has faults; but if his moral character is bad, nothing can keep him long on the elevation to which he has climbed,–no political friendships, no remembrance of services and deeds. If such a man as Bacon fell from his high estate for taking bribes,–although bribery was a common vice among the public characters of his day,–how could Burr escape ignominy for the murder of the greatest statesman of his age?

Yet Hamilton lives, although the victim of his rival. He lives in the nation’s heart, which cannot forget his matchless services. He is still the admiration of our greatest statesmen; he is revered, as Webster is, by jurists and enlightened patriots. No statesman superior to him has lived in this great country. He was a man who lived in the pursuit of truth, and in the realm of great ideas; who hated sophistries and lies, and sought to base government on experience and wisdom.

“Great were the boons which this pure patriot gave,

Doomed by his rival to an early grave;

A nation’s tears upon that grave were shed.

Oh, could the nation by his truths be led!

Then of a land, enriched from sea to sea,

Would other realms its earnest following be,

And the lost ages of the world restore

Those golden ages which the bards adore.”

Authorities.

Hamilton’s Works; Life of Alexander Hamilton, by J. T. Morse, Jr.; Life and Times of Hamilton, by S. M. Smucker; W. Coleman’s Collection of Facts on the Death of Hamilton; J. G. Baldwin’s Party Leaders; Dawson’s Correspondence with Jay; Bancroft’s History of the United States; Parton’s Life and Times of Aaron Burr; Eulogies, by H. G. Otis and Dr. Nott; The Federalist; Lives of Contemporaneous Statesmen; Sparks’s Life of Washington.

John Adams : Constructive Statesmanship

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XI : American Founders