Chrysostom : Sacred Eloquence – Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

Cyrus the Great : Asiatic Supremacy

Julius Caesar : Imperialism

Marcus Aurelius : Glory of Rome

Constantine the Great : Christianity Enthroned

Paula : Woman as Friend

Chrysostom : Sacred Eloquence

Saint Ambrose : Episcopal Authority

Saint Augustine : Christian Theology

Theodosius the Great : Latter Days of Rome

Leo the Great : Foundation of the Papacy

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IV : Imperial Antiquity

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

The power of the Pulpit

Eloquence always a power

The superiority of the Christian themes to those of Pagan antiquity

Sadness of the great Pagan orators

Cheerfulness of the Christian preachers

Chrysostom

Education

Society of the times

Chrysostom’s conversion, and life in retirement

Life at Antioch

Characteristics of his eloquence; his popularity as orator

His influence

Shelters Antioch from the wrath of Theodosius

Power and responsibility of the clergy

Transferred to Constantinople, as Patriarch of the East

His sermons, and their effect at Court

Quarrel with Eutropius

Envy of Theophilus of Alexandria

Council of the Oaks; condemnation to exile

Sustained by the people; recalled

Wrath of the Empress

Exile of Chrysostom

His literary labors in exile

His more remote exile, and death

His fame and influence

Chrysostom : Sacred Eloquence

A.D. 347-407.

The first great moral force, after martyrdom, which aroused the degenerate people of the old Roman world from the torpor and egotism and sensuality which were preparing the way for violence and ruin, was the Christian pulpit. Sacred eloquence, then, as impersonated in Chrysostom, “the golden-mouthed,” will be the subject of this Lecture, for it was by the “foolishness of preaching” that a new spiritual influence went forth to save a dying world. Chrysostom was not, indeed, the first great preacher of the new doctrines which were destined to win such mighty triumphs, but he was the most distinguished of the pulpit orators of the early Church. Yet even he is buried in his magnificent cause. Who can estimate the influence of the pulpit for fifteen hundred years in the various countries of Christendom? Who can grasp the range of its subjects and the dignity of its appeals? In ages even of ignorance and superstition it has been eloquent with themes of redemption and of a glorious immortality.

Eloquence has ever been admired and honored among all nations, especially among the Greeks. It was the handmaid of music and poetry when the divinity of mind was adored–perhaps with Pagan instincts, but still adored–as a birthright of genius, upon which no material estimate could be placed, since it came from the Gods, like physical beauty, and could neither be bought nor acquired. Long before Christianity declared its inspiring themes and brought peace and hope to oppressed millions, eloquence was a mighty power. But then it was secular and mundane; it pertained to the political and social aspects of States; it belonged to the Forum or the Senate; it was employed to save culprits, to kindle patriotic devotion, or to stimulate the sentiments of freedom and public virtue. Eloquence certainly did not belong to the priest. It was his province to propitiate the Deity with sacrifices, to surround himself with mysteries, to inspire awe by dazzling rites and emblems, to work on the imagination by symbols, splendid dresses, smoking incense, slaughtered beasts, grand temples. He was a man to conjure, not to fascinate; to kindle superstitious fears, not to inspire by thoughts which burn. The gift of tongues was reserved for rhetoricians, politicians, lawyers, and Sophists.

Now Christianity at once seized and appropriated the arts of eloquence as a means of spreading divine truth. Christianity ever has made use of all the arts and gifts and inventions of men to carry out the concealed purposes of the Deity. It was not intended that Christianity should always work by miracles, but also by appeals to the reason and conscience of mankind, and through the truths which had been supernaturally declared,–the required means to accomplish an end. Therefore, she enriched and dignified an art already admired and honored. She carried away in triumph the brightest ornament of the Pagan schools and placed it in the hands of her chosen ministers. So that the Christian pulpit soon began to rival the Forum in an eloquence which may be called artistic,–a natural power of moving men, allied with learning and culture and experience. Young men of family and fortune at last, like Gregory Nazianzen and Basil, prepared themselves in celebrated schools; for eloquence, though a gift, is impotent without study. See the labors of the most accomplished of the orators of Pagan antiquity. It was not enough for an ancient Greek to have natural gifts; he must train himself by the severest culture, mastering all knowledge, and learning how he could best adapt himself to those he designed to move. So when the gospel was left to do its own work on people’s hearts, after supernatural influence is supposed to have been withdrawn, the Christian preachers, especially in the Grecian cities, found it expedient to avail themselves of that culture which the Greeks ever valued, even in degenerate times. Indeed, when has Christianity rejected learning and refinement? Paul, the most successful of the apostles, was also the most accomplished,–even as Moses, the most gifted man among the ancient Jews, was also the most learned. It is a great mistake to suppose that those venerated Fathers, who swayed by their learning and eloquence the Christian world, were merely saints. They were the intellectual giants of their day, living in courts, and associating with the wise, the mighty, and the noble. And nearly all of them were great preachers: Cyprian, Athanasius, Augustine, Ambrose, and even Leo, if they yielded to Origen and Jerome in learning, were yet very polished, cultivated men, accustomed to all the refinements which grace and dignify society.

But the eloquence of these bishops and orators was rendered potent by vastly grander themes than those which had been dwelt upon by Pericles, or Demosthenes, or Cicero, and enlarged by an amazing depth of new subjects, transcending in dignity all and everything on which the ancient orators had discoursed or discussed. The bishop, while he baptized believers, and administered the symbolic bread and wine, also taught the people, explained to them the mysteries, enforced upon them their duties, appealed to their intellects and hearts and consciences, consoled them in their afflictions, stimulated their hopes, aroused their fears, and kindled their devotions. He plunged fearlessly into every subject which had a bearing on religious life. While he stood before them clad in the robes of priestly office, holding in his hands the consecrated elements which told of their redemption, and offering up to God before the altar prayers in their behalf, he also ascended the pulpit to speak of life and death in all their sublime relations. “There was nothing touching,” says Talfourd, “in the instability of fortune, in the fragility of loveliness, in the mutability of mortal friendship, or the decay of systems, nor in the fall of States and empires, which he did not present, to give humiliating ideas of worldly grandeur. Nor was there anything heroic in sacrifice, or grand in conflict, or sublime in danger,–nothing in the loftiness of the soul’s aspirations, nothing of the glorious promises of everlasting life,–which he did not dwell upon to stimulate the transported crowds who hung upon his lips. It was his duty and his privilege,” continues this eloquent and Christian lawyer, “to dwell on the older history of the world, on the beautiful simplicities of patriarchal life, on the stern and marvellous story of the Hebrews, on the glorious visions of the prophets, on the songs of the inspired melodists, on the countless beauties of the Scriptures, on the character and teachings and mission of the Saviour. It was his to trace the Spirit of the boundless and the eternal, faintly breathing in every part of the mystic circle of superstition,–unquenched even amidst the most barbarous rites of savage tribes, and in the cold and beautiful shapes of Grecian mould.”

How different this eloquence from that of the expiring nations! Their eloquence is sad, sounding like the tocsin of departed glories, protesting earnestly–but without effect–against those corruptions which it was too late to heal. How touching the eloquence of Demosthenes, pointing out the dangers of the State, and appealing to liberty, when liberty had fled. In vain his impassioned appeals to men insensible to elevated sentiments. He sang the death-song of departed greatness without the possibility of a new creation. He spoke to audiences cultivated indeed, but divided, enervated, embittered, infatuated, incapable of self-sacrifice, among whom liberty was a mere tradition and patriotism a dream; and he spoke in vain. Nor could Cicero–still more accomplished, if not so impassioned–kindle among the degenerate Romans the ancient spirit which had fled when demagogues began their reign. How mournful was the eloquence of this great patriot, this experienced statesman, this wise philosopher, who, in spite of all his weaknesses, was admired and honored by all who spoke the Latin tongue. But had he spoken with the tongue of an archangel it would have been all the same, on any worldly or political subject. The old sentiments had died out. Faith was extinguished amid universal scepticism and indifference. He had no material to work on. The birthright of ancient heroes had been sold for a mess of pottage, and this he knew; and therefore with his last philippics he bowed his venerable head, and prepared himself for the sword of the executioner, which he accepted as an inevitable necessity.

These great orators appealed to traditions, to sentiments which had passed away, to glories which could not possibly return; and they spoke in vain. All they could do was to utter their manly and noble protests, and die, with the dispiriting and hopeless feeling that the seeds of ruin, planted in a soil of corruption, would soon bear their wretched fruits,–even violence and destruction.

But the orators who preached a new religion of regenerating forces were more cheerful. They knew that these forces would save the world, whatever the depth of ignominy, wretchedness, and despair. Their eloquence was never sad and hopeless, but triumphant, jubilant, overpowering. It kindled the fires of an intense enthusiasm. It kindled an enthusiasm not based on the conquest of the earth, but on the conquests of the soul, on the never-fading glories of immortality, on the ever-increasing power of the kingdom of Christ. The new orators did not preach liberty, or the glories of material life, or the majesty of man, or even patriotism, but Salvation,–the future destinies of the soul. A new arena of eloquence was entered; a new class of orators arose, who discoursed on subjects of transcending comfort to the poor and miserable. They made political slavery of no account in comparison with the eternal redemption and happiness promised in the future state. The old institutions could not be saved: perhaps the orators did not care to save them; they were not worth saving; they were rotten to the core. But new institutions should arise upon their ruins; creation should succeed destruction; melodious birth-songs should be heard above the despairing death-songs. There should be a new heaven and a new earth, in which should dwell righteousness; and the Prince of Peace– Prophet, Priest, and King–should reign therein forever and ever.

Of the great preachers who appeared in thousands of pulpits in the fourth century,–after Christianity was seated on the throne of the Roman world, and before it had sunk into the eclipse which barbaric spoliations and papal usurpations, and general ignorance, madness, and violence produced,–there was one at Antioch (the seat of the old Greco-Asiatic civilization, alike refined, voluptuous, and intellectual) who was making a mighty stir and creating a mighty fame. This was Chrysostom, whose name has been a synonym of eloquence for more than fifteen hundred years. His father, named Secundus, was a man of high military rank; his mother, Anthusa, was a woman of rare Christian graces,–as endeared to the Church as Monica, the sainted mother of Augustine; or Nonna, the mother of Gregory Nazianzen. And it is a pleasing fact to record, that most of the great Fathers received the first impulse to their memorable careers from the influence of pious mothers; thereby showing the true destiny and glory of women, as the guardians and instructors of their children, more eager for their salvation than ambitious of worldly distinction. Buried in the blessed sanctities and certitudes of home,–if this can be called a burial,–those Christian women could forego the dangerous fascination of society and the vanity of being enrolled among its leaders. Anthusa so fortified the faith of her yet unconverted son by her wise and affectionate counsels, that she did not fear to intrust him to the teachings of Libanius, the Pagan rhetorician, deeming an accomplished education as great an ornament to a Christian gentleman as were the good principles she had instilled a support in dangerous temptation. Her son John–for that was his baptismal and only name–was trained in all the learning of the schools, and, like so many of the illustrious of our world, made in his youth a wonderful proficiency. He was precocious, like Cicero, like Abélard, like Pascal, like Pitt, like Macaulay, and Stuart Mill; and like them he panted for distinction and fame. The most common path to greatness for high-born youth, then as now, was the profession of the law. But the practice of this honorable profession did not, unfortunately, at least in Antioch, correspond with its theory. Chrysostom (as we will call him, though he did not receive this appellation until some centuries after his death) was soon disgusted and disappointed with the ordinary avocations of the Forum,–its low standard of virtue, and its diversion of what is ennobling in the pure fountains of natural justice into the turbid and polluted channels of deceit, chicanery, and fraud; its abandonment to usurious calculations and tricks of learned and legalized jugglery, by which the end of law itself was baffled and its advocates alone enriched. But what else could be expected of lawyers in those days and in that wicked city, or even in any city of the whole Empire, when justice was practically a marketable commodity; when one half of the whole population were slaves; when the circus and the theatre were as necessary as the bath; when only the rich and fortunate were held in honor; when provincial governments were sold to the highest bidder; when effeminate favorites were the grand chamberlains of emperors; when fanatical mobs rendered all order a mockery; when the greed for money was the master passion of the people; when utility was the watchword of philosophy, and material gains the end and object of education; when public misfortunes were treated with the levity of atheistic science; when private sorrows, miseries, and sufferings had no retreat and no shelter; when conjugal infelicities were scarcely a reproach; when divorces were granted on the most frivolous pretexts; when men became monks from despair of finding women of virtue for wives; and when everything indicated a rapid approach of some grand catastrophe which should mingle, in indiscriminate ruin, the masters and the slaves of a corrupt and prostrate world?

Such was society, and such the signs of the times, when Chrysostom began the practice of the law at Antioch,–perhaps the wickedest city of the whole Empire. His eyes speedily were opened. He could not sleep, for grief and disgust; he could not embark on a profession which then, at least, added to the evils it professed to cure; he began to tremble for his higher interests; he abandoned the Forum forever; he fled as from a city of destruction; he sought solitude, meditation, and prayer, and joined those monks who lived in cells, beyond the precincts of the doomed city. The ardent, the enthusiastic, the cultivated, the conscientious, the lofty Chrysostom fraternized with the visionary inhabitants of the desert, speculated with them on the mystic theogonies of the East, discoursed with them on the origin of evil, studied with them the Christian mysteries, fasted with them, prayed with them, slept like them on a bed of straw, denied himself his accustomed luxuries, abandoning himself to alternate transports of grief and sublime enthusiasm, now contending with the demons who sought his destruction; then soaring to comprehend the Man-God,–the Word made flesh, the incarnation of the divine Logos,–and the still more subtile questions pertaining to the nature and distinctions of the Trinity.

Such were the forms and modes of his conversion,–somewhat different from the experience of Augustine or of Luther, yet not less real and permanent. Those days were the happiest of his life. He had leisure and he had enthusiasm. He desired neither riches nor honors, but the peace of a forgiven soul He was a monk without losing his humanity; a philosopher without losing his taste for the Bible; a Christian without repudiating the learning of the schools. But the influence of early education, his practical yet speculative intellect, his inextinguishable sympathies, his desire for usefulness, and possibly an unsubdued ambition to exert a greater influence would not allow him wholly to bury himself. He made long visits to the friends and habitations he had left, in order to stimulate their faith, relieve their necessities, and encourage them in works of benevolence; leading a life of alternate study and active philanthropy,–learning from the accomplished Diodorus the historical mode of interpreting the Scriptures, and from the profound Theodorus the systems of ancient philosophy. Thus did he train himself for his future labors, and lay the foundation for his future greatness. It was thus he accumulated those intellectual treasures which he afterwards lavished at the imperial court.

But his health at last gave way; and who can wonder? Who can long thrive amid exhausting studies on root dinners and ascetic severities? He was obliged to leave his cave, where he had dwelt six blessed years; and the bishop of Antioch, who knew his merits, pressed him into the active service of the Church, and ordained him deacon,–for the hierarchy of the Church was then established, whatever may have been the original distinctions of the clergy. With these we have nothing to do. But it does not appear that he preached as yet to the people, but performed like other deacons the humble office of reader, leaving to priests and bishops the higher duties of a public teacher. It was impossible, however, for a man of his piety and his gifts, his melodious voice, his extensive learning, and his impressive manners long to remain in a subordinate post. He was accordingly ordained a presbyter, A.D. 381, by Bishop Flavian, in the spacious basilica of Antioch, and the active labors of his life began at the age of thirty-four.

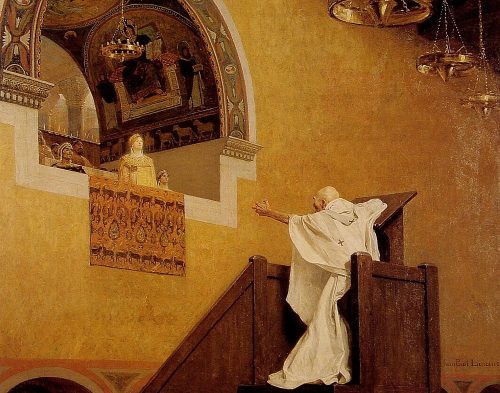

Many were the priests associated with him in that great central metropolitan church; “but upon him was laid the duty of especially preaching to the people,–the most important function recognized by the early Church. He generally preached twice in the week, on Saturday and Sunday mornings, often at break of day, in consequence of the heat of the sun. And such was his popularity and unrivalled power, that the bishop, it is said, often allowed him to finish what he had himself begun. His listeners would crowd around his pulpit, and even interrupt his teachings by their applause. They were unwearied, though they stood generally beyond an hour. His elocution, his gestures, and his matter were alike enchanting.” Like Bernard, his very voice would melt to tears. It was music singing divine philosophy; it was harmony clothing the richest moral wisdom with the most glowing style. Never, since the palmy days of Greece, had her astonishing language been wielded by such a master. He was an artist, if sacred eloquence does not disdain that word. The people were electrified by the invectives of an Athenian orator, and moved by the exhortations of a Christian apostle. In majesty and solemnity the ascetic preacher was a Jewish prophet delivering to kings the unwelcome messages of divine Omnipotence. In grace of manner and elegance of language he was the persuasive advocate of the ancient Forum; in earnestness and unction he has been rivalled only by Savonarola; in dignity and learning he may remind us of Bossuet; in his simplicity and orthodoxy he was the worthy successor of him who preached at the day of Pentecost. He realized the perfection which sacred eloquence attained, but to which Pagan art has vainly aspired,–a charm and a wonder to both learned and unlearned,–the precursor of the Bourdaloues and Lacordaires of the Roman Catholic Church, but especially the model for “all preachers who set above all worldly wisdom those divine revelations which alone can save the world.”

Everything combined to make Chrysostom the pride and the glory of the ancient Church,–the doctrines which he did not hesitate to proclaim to unwilling ears, and the matchless manner in which he enforced them,–perhaps the most remarkable preacher, on the whole, that ever swayed an audience; uniting all things,–voice, language, figure, passion, learning, taste, art, piety, occasion, motive, prestige, and material to work upon. He left to posterity more than a thousand sermons, and the printed edition of all his works numbers twelve folio volumes. Much as we are inclined to underrate the genius and learning of other days in this our age of more advanced utilities, of progressive and ever-developing civilization,–when Sabbath-school children know more than sages knew two thousand years ago, and socialistic philanthropists and scientific savans could put to blush Moses and Solomon and David, to say nothing of Paul and Peter, and other reputed oracles of the ancient world, inasmuch as they were so weak and credulous as to believe in miracles, and a special Providence, and a personal God,–yet we find in the sermons of Chrysostom, preached even to voluptuous Syrians, no commonplace exhortations, such as we sometimes hear addressed to the thinkers of this generation, when poverty of thought is hidden in pretty expressions, and the waters of life are measured out in tiny gill cups, and even then diluted by weak platitudes to suit the taste of the languid and bedizened and frivolous slaves of society, whose only intellectual struggle is to reconcile the pleasures of material and sensual life with the joys and glories of the world to come. He dwelt, boldly and earnestly, and with masculine power, on the majesty of God and the comparative littleness of man, on moral accountability to Him, on human degeneracy, on the mysterious power of evil, by force of which good people in this dispensation are in a small minority, on the certainty of future retribution; yet also on the never-fading glories of immortality which Christ has brought to light by his sufferings and death, his glorious resurrection and ascension, and the promised influences of the Holy Spirit. These truths, so solemn and so grand, he preached, not with tricks of rhetoric, but simply and urgently, as an ambassador of Heaven to lost and guilty man. And can you wonder at the effect? When preachers throw themselves on the cardinal truths of Christianity, and preach with earnestness as if they believed them, they carry the people with them, producing a lasting impression, and growing broader and more dignified every day. When they seek novelties, and appeal purely to the intellect, or attempt to be philosophical or learned, they fail, whatever their talents. It is the divine truth which saves, not genius and learning,–especially the masses, and even the learned and rich, when their eyes are opened to the delusions of life.

For twelve years Chrysostom preached at Antioch, the oracle and the friend of all classes whether high or low, rich or poor, so that he became a great moral force, and his fame extended to all parts of the Empire. Senators and generals and governors came to hear his eloquence. And when, to his vast gifts, he added the graces and virtues of the humblest of his flock,–parting with a splendid patrimony to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, utterly despising riches except as a means of usefulness, living most abstemiously, shunning the society of idolaters, indefatigable in labor, accessible to those who needed spiritual consolation, healing dissensions, calming mobs, befriending the persecuted, rebuking sin in high places; a man acquainted with grief in the midst of intoxicating intellectual triumphs,–reverence and love were added to admiration, and no limits could be fixed to the moral influence he exerted.

There are few incidents in his troubled age more impressive than when this great preacher sheltered Antioch from the vengeance of Theodosius. That thoughtless and turbulent city had been disgraced by an outrageous insult to the emperor. A mob, a very common thing in that age, had rebelled against the majesty of the law, and murdered the officers of the Government. The anger of Theodosius knew no bounds, but was fortunately averted by the entreaties of the bishop, and the emperor abstained from inflicting on the guilty city the punishment he afterwards sent upon Thessalonica for a less crime. Moreover the repentance of the people was open and profound. Chrysostom had moved and melted them. It was the season of Lent. Every day the vast church was crowded. The shops were closed; the Forum was deserted; the theatre was shut; the entire day was consumed with public prayers; all pleasures were forsaken; fear and anguish sat on every countenance, as in a Mediaeval city after an excommunication. Chrysostom improved the occasion; and perhaps the most remarkable Lenten sermons ever preached, subdued the fierce spirits of the city, and Antioch was saved. It was certainly a sublime spectacle to see a simple priest, unclothed even with episcopal functions, surrounded for weeks by the entire population of a great city, ready to obey his word, and looking to him alone as their deliverer from temporal calamities, as well as their guide in fleeing from the wrath to come.

And here we have a noted example of the power as well as the dignity of the pulpit,–a power which never passed away even in ages of superstition, never disdained by abbots or prelates or popes in the plenitude of their secular magnificence (as we know from the sermons of Gregory and Bernard); a sacred force even in the hands of monks, as when Savonarola ruled the city of Florence, and Bourdaloue awed the court of France; but a still greater force among the Reformers, like Luther and Knox and Latimer, yea in all the crises and changes of both the Catholic and Protestant churches; and not to be disdained even in our utilitarian times, when from more than two hundred thousand pulpits in various countries of Christendom, every Sunday, there go forth voices, weak or strong, from gifted or from shallow men, urging upon the people their duties, and presenting to them the hopes of the life to come. Oh, what a power is this! How few realize its greatness, as a whole! What a power it is, even in its weaker forms, when the clergy abdicate their prerogatives and turn themselves into lecturers, or bury themselves in liturgies! But when they preach without egotism or vanity, scorning sensationalism and vulgarity and cant, and falling back on the great truths which save the world, then sacredness is added to dignity. And especially when the preacher is fearless and earnest, declaring most momentous truths, and to people who respond in their hearts to those truths, who are filled with the same enthusiasm as he is himself, and who catch eagerly his words of life, and follow his directions as if he were indeed a messenger of Jehovah,–then I know of no moral power which can be compared with the pulpit. Worldly men talk of the power of the press, and it is indeed an influence not to be disdained,–it is a great leaven; but the teachings of its writers, when not superficial, are contradictory, and are often mere echoes of public sentiment in reference to mere passing movements and fashions and politics and spoils. But the declarations of the clergy, for the most part, are all in unison, in all the various churches–Catholic and Protestant, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Methodist and Baptist–which accept God Almighty as the moral governor of the universe, the great master of our destinies, whose eternal voice speaketh to the conscience of mankind. And hence their teachings, if they are true to their calling, have reference to interests and duties and aspirations and hopes as far removed in importance from mere temporal matters as the heaven is higher than the earth. Oh, what high treason to the deity whom the preacher invokes, what stupidity, what frivolity, what insincerity, what incapacity of realizing what is truly great, when he descends from the lofty themes of salvation and moral accountability, to dwell on the platitudes of aesthetic culture, the beauties and glories of Nature, or the wonders of a material civilization, and then with not half the force of those books and periodicals which are scattered in every hamlet of civilized Europe and America!

Now it was to the glory of Chrysostom that he felt the dignity of his calling and aspired to nothing higher, satisfied with his great vocation,–a vocation which can never be measured by the lustre of a church or the wealth of a congregation. Gregory Nazianzen, whether preaching in his paternal village or in the cathedral of Constantinople, was equally the creator of those opinion-makers who settle the verdicts of men. Augustine, in a little African town, wielded ten times the influence of a bishop of Rome, and his sermons to the people of the town of Hippo furnished a thesaurus of divinity to the clergy for a thousand years.

Nevertheless, Antioch was not great enough to hold such a preacher as Chrysostom. He was summoned by imperial authority to the capital of the Eastern Empire. One of the ministers of Arcadius, the son of the great Theodosius, had heard him preach, and greatly admired his eloquence, and perhaps craved the excitement of his discourses,–as the people of Rome hankered after the eloquence of Cicero when he was sent into exile. Chrysostom reluctantly resigned his post in a provincial city to become the Patriarch of Constantinople. It was a great change in his outward dignity. His situation as the highest prelate of the East was rarely conferred except on the favorites of emperors, as the episcopal sees of Mediaeval Europe were rarely given to men but of noble birth. Yet being forced, as it were, to accept what he did not seek or perhaps desire, he resolved to be true to himself and his master. Scarcely was he consecrated by Theophilus of Alexandria before he launched out his indignant invectives against the patron who had elevated him, the court which admired him, and the imperial family which sustained him. Still the preacher, when raised to the government of the Eastern church, regarding his sphere in the pulpit as the loftiest which mortal genius could fill. He feared no one, and he spared no one. None could rob a man who had parted with a princely fortune for the sake of Christ; none could bribe a man who had no favors to ask, and who could live on a crust of bread; none could silence a man who felt himself to be the minister of divine Omnipotence, and who scattered before his altar the dust of worldly grandeur.

It seems that Chrysostom regarded his first duty, even as the Metropolitan of the East, to preach the gospel. He subordinated the bishop to the preacher. True, he was the almoner of his church and the director of its revenues; but he felt that the church of Christ had a higher vocation for a bishop to fill than to be a good business man. Amid all the distractions of his great office he preached as often and as fervently as he did at Antioch. Though possessed of enormous revenues, he curtailed the expenses of his household, and surrounded himself with the pious and the learned. He lived retired within his palace; he dined alone on simple food, and always at home. The great were displeased that he would not honor with his presence their sumptuous banquets; but rich dinners did not agree with his weak digestion, and perhaps he valued too highly his precious time to waste himself, body and soul, for the enjoyment of even admiring courtiers. His power was not at the dinner-table but in the pulpit, and he feared to weaken the effects of his discourses by the exhibition of weaknesses which nearly every man displays amid the excitements of social intercourse.

Perhaps, however, Chrysostom was too ascetic. Christ dined with publicans and sinners; and a man must unbend somewhere, or he loses the elasticity of his mind, and becomes a formula or a mechanism. The convivial enjoyments of Luther enabled him to bear his burden. Had Thomas à Becket shown the same humanity as archbishop that he did as chancellor, he might not have quarrelled with his royal master. So Chrysostom might have retained his favor with the court and his see until he died, had he been less austere and censorious. Yet we should remember that the asceticism which is so repulsive to us, and with reason, and which marked the illustrious saints of the fourth century, was simply the protest against the almost universal materialism of the day,–that dreadful moral blight which was undermining society. As luxury and extravagance and material pleasures were the prominent evils of the old Roman world in its decline, it was natural that the protest against these evils should assume the greatest outward antagonism. Luxury and a worldly life were deemed utterly inconsistent with a preacher of righteousness, and were disdained with haughty scorn by the prophets of the Lord, as they were by Elijah and Elisha in the days of Ahab. “What went ye out in the wilderness to see?” said our Lord, with disdainful irony,–“a man clothed in soft raiment? They that wear soft clothing are in king’s houses,”–as much as to say, My prophets, my ministers, rejoice not in such things.

So Chrysostom could never forget that he was a minister of Christ, and was willing to forego the trappings and pleasures of material life sooner than abdicate his position as a spiritual dictator. The secular historians of our day would call him arrogant, like the courtiers of Arcadius, who detested his plain speaking and his austere piety; but the poor and unimportant thought him as humble as the rich and great thought him proud. Moreover, he was a foe to idleness, and sent away from court to their distant sees a host of bishops who wished to bask in the sunshine of court favor, or revel in the excitements of a great city; and they became his enemies. He deposed others for simony, and they became still more hostile. Others again complained that he was inhospitable, since he would not give up his time to everybody, even while he scattered his revenues to the poor. And still others entertained towards him the passion of envy,–that which gives rancor to the odium theologicum, that fatal passion which caused Daniel to be cast into the lions’ den, and Haman to plot the ruin of Mordecai; a passion which turns beautiful women into serpents, and learned theologians into fiends. So that even Chrysostom was assailed with danger. Even he was not too high to fall.

The first to turn against the archbishop was the Lord High Chamberlain,–Eutropius,–the minister who had brought him to Constantinople. This vulgar-minded man expected to find in the preacher he had elevated a flatterer and a tool. He was as much deceived as was Henry II. when he made Thomas à Becket archbishop of Canterbury. The rigid and fearless metropolitan, instead of telling stories at his table and winking at his infamies, openly rebuked his extortions and exposed his robberies. The disappointed minister of Arcadius then bent his energies to compass the ruin of the prelate; but, before he could effect his purpose, he was himself disgraced at court. The army in revolt had demanded his head, and Eutropius fled to the metropolitan church of Saint Sophia. Chrysostom seized the occasion to impress his hearers with the instability of human greatness, and preached a sort of funeral oration for the man before he was dead. As the fallen and wretched minister of the emperor lay crouching in an agony of shame and fear beneath the table of the altar, the preacher burst out: “Oh, vanity of vanities, where is now the glory of this man? Where the splendor of the light which surrounded him; where the jubilee of the multitude which applauded him; where the friends who worshipped his power; where the incense offered to his image? All gone! It was a dream: it has fled like a shadow; it has burst like a bubble! Oh, vanity of vanity of vanities! Write it on all walls and garments and streets and houses: write it on your consciences. Let every one cry aloud to his neighbor, Behold, all is vanity! And thou, O wretched man,” turning to the fallen chamberlain, “did I not say unto thee that money is a thankless servant? Said I not that wealth is a most treacherous friend? The theatre, on which thou hast bestowed honor, has betrayed thee; the race-course, after devouring thy gains, has sharpened the sword of those whom thou hast labored to amuse. But our sanctuary, which thou hast so often assailed, now opens her bosom to receive thee, and covers thee with her wings.”

But even the sacred cathedral did not protect him. He was dragged out and slain.

A more relentless foe now appeared against the prelate,–no less a personage than Theophilus, the very bishop who had consecrated him. Jealousy was the cause, and heresy the pretext,–that most convenient cry of theologians, often indeed just, as when Bernard accused Abélard, and Calvin complained of Servetus; but oftener, the most effectual way of bringing ruin on a hated man, as when the partisans of Alexander VI. brought Savonarola to the tribunal of the Inquisition. It seems that Theophilus had driven out of Egypt a body of monks because they would not assent to the condemnation of Origen’s writings; and the poor men, not knowing where to go, fled to Constantinople and implored the protection of the Patriarch. He compassionately gave them shelter, and permission to say their prayers in one of his churches. Therefore he was a heretic, like them,–a follower of Origen.

Under common circumstances such an accusation would have been treated with contempt. But, unfortunately, Chrysostom had alienated other bishops also. Yet their hostility would not have been heeded had not the empress herself, the beautiful and the artful Eudoxia, sided against him. This proud, ambitious, pleasure-seeking, malignant princess–in passion a Jezebel, in policy a Catherine de Medici, in personal fascination a Mary Queen of Scots–hated the archbishop, as Mary hated John Knox, because he had ventured to reprove her levities and follies; and through her influence (and how great is the influence of a beautiful woman on an irresponsible monarch!) the emperor, a weak man, allowed Theophilus to summon and preside over a council for the trial of Chrysostom. It assembled at a place called the Oaks, in the suburbs of Chalcedon, and was composed entirely of the enemies of the Patriarch. Nothing, however, was said about his heresy: that charge was ridiculous. But he was accused of slandering the clergy–he had called them corrupt; of having neglected the duties of hospitality, for he dined generally alone; of having used expressions unbecoming of the house of God, for he was severe and sarcastic; of having encroached on the jurisdiction of foreign bishops in having shielded a few excommunicated monks; and of being guilty of high treason, since he had preached against the sins of the empress. On these charges, which he disdained to answer, and before a council which he deemed illegal, he was condemned; and the emperor accepted the sentence, and sent him into exile.

But the people of Constantinople would not let him go. They drove away his enemies from the city; they raised a sedition and a seasonable earthquake, as Gibbon might call it, and having excited superstitious fears, the empress caused him to be recalled. His return, of course, was a triumph. The people spread their garments in his way, and conducted him in pomp to his archiepiscopal throne. Sixty bishops assembled and annulled the sentence of the Council of the Oaks. He was now more popular and powerful than before. But not more prudent. For a silver statue of the empress having been erected so near to the cathedral that the games instituted to its honor disturbed the services of the church, the bishop in great indignation ascended the pulpit, and declaimed against female vices. The empress at this was furious, and threatened another council. Chrysostom, still undaunted, then delivered that celebrated sermon, commencing thus: “Again Herodias raves; again she dances; again she demands the head of John in a basin.” This defiance, which was regarded as an insult, closed the career of Chrysostom in the capital of the Empire. Both the emperor and empress determined to silence him. A new council was convened, and the Patriarch was accused of violating the canons of the Church. It seems he ventured to preach before he was formally restored, and for this technical offence he was again deposed. No second earthquake or popular sedition saved him. He had sailed too long against the stream. What genius and what fame can protect a man who mocks or defies the powers that be, whether kings or people? If Socrates could not be endured at Athens, if Cicero was banished from Rome, how could this unarmed priest expect immunity from the possessors of absolute power whom he had offended? It is the fate of prophets to be stoned. The bold expounders of unpalatable truth ever have been martyrs, in some form or other.

But Chrysostom met his fate with fortitude, and the only favor which he asked was to reside in Cyzicus, near Nicomedia. This was refused, and the place of his exile was fixed at Cucusus,–a remote and desolate city amid the ridges of Mount Taurus; a distance of seventy days’ journey, which he was compelled to make in the heat of summer.

But he lived to reach this dreary resting-place, and immediately devoted himself to the charms of literary composition and letters to his friends. No murmurs escaped him. He did not languish, as Cicero did in his exile, or even like Thiers in Switzerland. Banishment was not dreaded by a man who disdained the luxuries of a great capital, and who was not ambitious of power and rank. Retirement he had sought, even in his youth, and it was no martyrdom to him so long as he could study, meditate, and write.

So Chrysostom was serene, even cheerful, amid the blasts of a cold and cheerless climate. It was there he wrote those noble and interesting letters, of which two hundred and forty still remain. Indeed, his influence seemed to increase with his absence from the capital; and this his enemies beheld with the rage which Napoleon felt for Madame de Staël when he had banished her to within forty leagues of Paris. So a fresh order from the Government doomed him to a still more dreary solitude, on the utmost confines of the Roman Empire, on the coast of the Euxine, even the desert of Pityus. But his feeble body could not sustain the fatigues of this second journey. He was worn out with disease, labors, and austerities; and he died at Comono, in Pontus,–near the place where Henry Martin died,–in the sixtieth year of his age, a martyr, like greater men than he.

Nevertheless this martyrdom, and at the hands of a Christian emperor, filled the world with grief. It was only equalled in intensity by the martyrdom of Becket in after ages. The voice of envy was at last hushed; one of the greatest lights of the Church was extinguished forever. Another generation, however, transported his remains to the banks of the Bosporus, and the emperor–the second Theodosius–himself advanced to receive them as far as Chalcedon, and devoutly kneeling before his coffin, even as Henry II. kneeled at the shrine of Becket, invoked the forgiveness of the departed saint for the injustice and injuries he had received. His bones were interred with extraordinary pomp in the tomb of the apostles, and were afterwards removed to Rome, and deposited, still later, beneath a marble mausoleum in a chapel of Saint Peter, where they still remain.

Such were the life and death of the greatest pulpit orator of Christian antiquity. And how can I describe his influence? His sermons, indeed, remain; but since we have given up the Fathers to the Catholics, as if they had a better right to them than we, their writings are not so well known as they ought to be,–as they will be, when we become broader in our views and more modest of our own attainments. Few of the Protestant divines, whom we so justly honor, surpassed Chrysostom in the soundness of his theology, and in the learning with which he adorned his sermons. Certainly no one of them has equalled him in his fervid, impassioned, and classic eloquence. He belongs to the Church universal. The great divines of the seventeenth century made him the subject of their admiring study. In the Middle Ages he was one of the great lights of the reviving schools. Jeremy Taylor, not less than Bossuet, acknowledged his matchless services. One of his prayers has entered into the beautiful liturgy of Cranmer. He was a Bernard, a Bourdaloue, and a Whitefield combined, speaking in the language of Pericles, and on themes which Paganism never comprehended and the Middle Ages but imperfectly discussed.

The permanent influence of such a man can only be measured by the dignity and power of the pulpit itself in all countries and in all ages. So far as pulpit eloquence is an art, its greatest master still speaketh. But greater than his art was the truth which he unfolded and adorned. It is not because he held the most cultivated audiences of his age spell-bound by his eloquence, but because he did not fear to deliver his message, and because he magnified his office, and preached to emperors and princes as if they were ordinary men, and regarded himself as the bearer of most momentous truth, and soared beyond human praises, and forgot himself in his cause, and that cause the salvation of souls,–it is for these things that I most honor him, and believe that his name will be held more and more in reverence, as Christianity becomes more and more the mighty power of the world.

Authorities.

Theodoret; Socrates; Sozomen; Gregory Nazianzen’s Orations; the Works of Chrysostom; Baronius’s Annals; Epistle of Saint Jerome; Tillemont’s Ecclesiastical History; Mabillon; Fleury’s Ecclesiastical History; Life of Chrysostom by Monard,–also a Life, by Frederic M. Perthes, translated by Professor Hovey; Neander’s Church History; Gibbon; Milman; Du Pin; Stanley’s Lectures on the Eastern Church. The Lives of the Fathers have been best written by Frenchmen, and by Catholic historians.