Daniel Webster : The American Union – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders by John Lord

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders

Andrew Jackson : Personal Politics

Henry Clay : Compromise Legislation

Daniel Webster : The American Union

John C. Calhoun : The Slavery Question

Abraham Lincoln : Civil War and Preservation of the Union

Robert E. Lee : The Southern Confederacy

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Leaders

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

General character and position of Webster

Birth and early life

Begins law-practice; enters Congress

His legal career

His oratory

Congressional services; finance

Industrial questions

Defender of the Constitution

Reply to Hayne of South Carolina

Webster’s ambition

His political relations to the South

The antislavery agitation

Webster’s 7th of March Speech

His loyalty to the Constitution and the Union

His political errors

Greatness and worth of his career

His death

His defects of character

His counterbalancing virtues

Permanence of his ideas and his fame

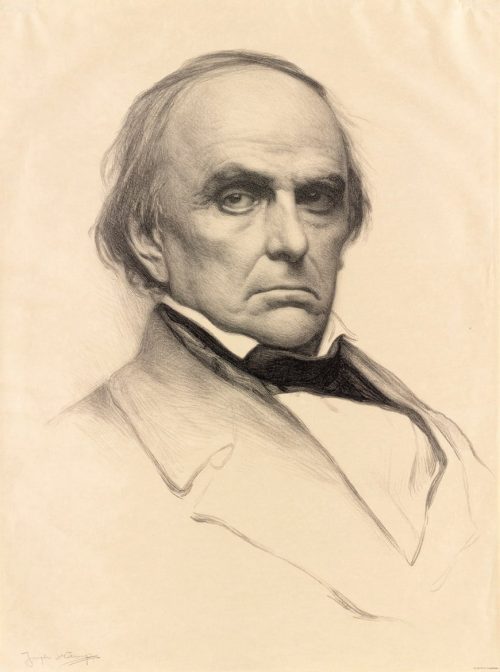

Daniel Webster : The American Union

A.D. 1782-1852.

If I were required to single out the most prominent political genius in the history of the United States, after the death of Hamilton, I should say it was Daniel Webster. He reigned for thirty years as a political dictator to his party, and at the same time was the acknowledged head of the American Bar. He occupied two spheres, in each of which he gained pre-eminence. But for envy, and the enemies he made, he probably would have reached the highest honor that the nation had to bestow. His influence was vast, until those discussions arose which provoked one of the most gigantic wars of modern times. For a generation he was the object of universal admiration for his eloquence and power. In political wisdom and experience he had no contemporaneous superior; there was no public man from 1820 to 1850 who had so great a prestige, and whose name and labors are so well remembered. His speeches and forensic arguments are more often quoted than those of any other statesman and lawyer the country has produced. His works are in every library, and are still read. His fame has not waned, in spite of the stirring events which have taken place since his death. Great generals have arisen and passed out of mind, but the name and memory of Webster are still fresh. Amid the tumults and parties of the war he foresaw and dreaded, his glory may have passed through an eclipse, but his name is to-day one of the proudest connected with our history. Living men, occupying great official positions, are of course more talked about and thought of than he; but of those illustrious characters who figured in public affairs a generation ago, no one has so great a posthumous fame and influence as the distinguished senator from Massachusetts. No man since the days of Jefferson is seated on a loftier pedestal; and no one is likely to live longer, if not in the nation’s heart, yet in its admiration for intellectual superiority and respect for political services. While he reigned as a political oracle for more than thirty years,–almost an idol in the eyes of his constituents,–it was his misfortune to be dethroned and reviled, in the last ten years of his life, by the very people who had exalted and honored him, and at last to die broken-hearted, from the loss of his well-earned popularity and the failure of his ambitious expectations. His life is sad as well as proud, like that of so many other great men who at one time led, and at another time opposed, popular sentiments. Their names stand out on every page of history, examples of the mutability of fortune,–alike joyous and saddened men, reaping both glory and shame; and sometimes glory for what is evil, and shame for what is good.

When Daniel Webster was born,–1782, in Salisbury, New Hampshire, near the close of our Revolutionary struggle,—there were very few prominent and wealthy families in New England, very few men more respectable than the village lawyers, doctors, and merchants, or even thrifty and intelligent farmers. Very few great fortunes had been acquired, and these chiefly by the merchants of Boston, Salem, Portsmouth, and other seaports whose ships had penetrated to all parts of the world Webster sprang from the agricultural class,–larger then in proportion to the other classes than now at the East,–at a time when manufactures were in their infancy and needed protection; when travel was limited; when it was a rare thing for a man to visit Europe; when the people were obliged to practise the most rigid economy; when everybody went to church; when religious scepticism sent those who avowed it to Coventry; when ministers were the leading power; when the press was feeble, and elections were not controlled by foreign immigrants; when men drank rum instead of whiskey, and lager beer had never been heard of, nor the great inventions and scientific wonders which make our age an era had anywhere appeared. The age of progress had scarcely then set in, and everybody was obliged to work in some way to get an honest living; for the Revolutionary War had left the country poor, and had shut up many channels of industry. The farmers at that time were the most numerous and powerful class, sharp, but honest and intelligent; who honored learning, and enjoyed discussions on metaphysical divinity. Their sons did not then leave the paternal acres to become clerks in distant cities; nor did their daughters spend their time in reading French novels, or sneering at rustic duties and labors. This age of progress had not arisen when everybody looks forward to a millennium of idleness and luxury, or to a fortune acquired by speculation and gambling rather than by the sweat of the brow,–an age, in many important respects, justly extolled, especially for scientific discoveries and mechanical inventions, yet not remarkable for religious earnestness or moral elevation.

The life of Daniel Webster is familiar to all intelligent people. His early days were spent amid the toils and blessedness of a New England farm-house, favored by the teachings of intelligent, God-fearing parents, who had the means to send him to Phillips Academy in Exeter, then recently founded, where he fitted for college, and shortly after entered Dartmouth, at the age of fifteen. In connection with Webster, I do not read of any remarkable precocity, at school or college, such as marked Cicero, Macaulay, and Gladstone; but it seems that he won the esteem of both teachers and students, and was regarded as a very promising youth. After his graduation he taught an academy at Fryeburg, for a time, and then began the study of the law,–first at Salisbury, and subsequently in Boston, in the office of the celebrated Governor Gore. He was admitted to the bar in 1805, and established himself in Boscawen, but soon afterwards removed to Portsmouth, where he entered on a large practice, encountering such able lawyers as Jeremiah Mason and Jeremiah Smith, who both became his friends and admirers, for Webster’s legal powers were soon the talk of the State. At the early age of thirty-one he entered Congress (1813), and took the whole House by surprise with his remarkable speeches, during the war with Great Britain,–on such topics as the enlargement of the navy, the repeal of the embargo, and the complicated financial questions of the day. In 1815 he retired awhile from public life, and removed to Boston, where he enjoyed a lucrative practice. In 1822 he re-entered Congress. So popular was he at this time, that, on his re-election to Congress in 1824, he received four thousand nine hundred and ninety votes out of five thousand votes cast. In 1827 he entered the Senate, where he was to reign as one of its greatest chiefs,–the idol of his party in New England, practising his profession at the same time, a leader of the American Bar, and an oracle in politics on all constitutional questions.

With this rapid sketch, I proceed to enumerate the services of Daniel Webster to his country, since on these enduring fame and gratitude are based. And first, I allude to his career as a lawyer,–not a narrow, technical lawyer, seeking to gain his case any way he can, with an eye on pecuniary rewards alone, but a lawyer devoting himself to the study of great constitutional questions and fundamental principles. In his legal career, when for nearly forty years he discussed almost every issue that can arise between individuals and communities, some half-a-dozen cases have become historical, because of the importance of the principles and interests involved. In the Gibbons and Ogden case he assumed the broad ground that the grant of power to regulate commerce was exclusively the right of the General Government. William Wirt, his distinguished antagonist,–then at the height of his fame,–relied on the coasting license given by States; but the lucid and luminous arguments of the young lawyer astonished the court, and made old Judge Marshall lay down his pen, drop back in his chair, turn up his coat-cuffs, and stare at the speaker in amazement at his powers.

The first great case which gave Webster a national reputation was that pertaining to Dartmouth College, his alma mater, which he loved as Newton loved Cambridge. The college was in the hands of politicians, and Webster recovered the college from their hands and restored it to the trustees, laying down such broad principles that every literary and benevolent institution in this land will be grateful to him forever. This case, which was argued with consummate ability, and with words as eloquent as they were logical and lucid, melting a cold court into tears, placed Webster in the front rank of lawyers, which he kept until he died. In the Ogden and Saunders case he settled the constitutionality of State bankrupt laws; in that of the United States Bank he maintained the right of a citizen of one State to perform any legal act in another; in that which related to the efficacy of Stephen Girard’s will, he demonstrated the vital importance of Christianity to the success of free institutions,–so that this very college, which excluded clergymen from being teachers in it, or even visiting it, has since been presided over by laymen of high religious character, like Judge Jones and Doctor Allen. In the Rhode Island case he proved the right of a State to modify its own institutions of government. In the Knapp murder case he brought out the power of conscience–the voice of God to the soul–with such terrible forensic eloquence that he was the admiration of all Christian people. No better sermon was ever preached than this appeal to the conscience of men.

In these and other cases he settled very difficult and important questions, so that the courts of law will long be ruled by his wisdom. He enriched the science of jurisprudence itself by bringing out the fundamental laws of justice and equity on which the whole science rests. He was not as learned as he was logical and comprehensive. His greatness as a lawyer consisted in seeing and seizing some vital point not obvious, or whose importance was not perceived by his opponent, and then bringing to bear on this point the whole power of his intellect. His knowledge was marvellous on those points essential to his argument; but he was not probably learned, like Kent, in questions outside his cases,–I mean the details and technicalities of law. He did, however, know the fundamental principles on which his great cases turned, and these he enforced with much eloquence and power, so that his ablest opponents quailed before him. Perhaps his commanding presence and powerful tones and wonderful eye had something to do with his success at the Bar as well as in the Senate,–a brow, a voice, and an eye that meant war when he was fairly aroused; although he appealed generally to reason, without tricks of rhetoric. If he sometimes intimidated, he rarely resorted to exaggerations, but confined himself strictly to the facts, so that he seemed the fairest of men. This moderation had great weight with an intelligent jury and with learned judges. He always paid great deference to the court, and was generally courteous to his opponents. Of all his antagonists at the Bar, perhaps it was Jeremiah Mason and Rufus Choate whom he most dreaded; yet both of these great men were his warm friends. Warfare at the Bar does not mean personal animosity,–it is generally mutual admiration, except in the antagonism of such rivals as Hamilton and Burr. Webster’s admiration for Wirt, Pinkney, Curtis, and Mason was free from all envy; in fact, Webster was too great a man for envy, and great lawyers were those whom he loved best, whom he felt to be his brethren, not secret enemies. His admiration for Jeremiah Mason was only equalled by that for Judge Marshall, who was not a rival. Webster praised Marshall as he might have Erskine or Lyndhurst.

Mr. Webster, again, attained to great eminence in another sphere, in which lawyers have not always succeeded,–that of popular oratory, in the shape of speeches and lectures and orations to the people directly. In this sphere I doubt if he ever had an equal in this country, although Edward Everett, Rufus Choate, Wendell Phillips, and others were distinguished for their popular eloquence, and in some respects were the equals of Webster. But he was a great teacher of the people, directly,–a sort of lecturer on the principles of government, of finance, of education, of agriculture, of commerce. He was superbly eloquent in his eulogies of great men like Adams and Jefferson. His Bunker Hill and Plymouth addresses are immortal. He lectured occasionally before lyceums and literary institutions. He spoke to farmers in their agricultural meetings, and to merchants in marts of commerce. He did not go into political campaigns to any great extent, as is now the custom with political leaders on the eve of important elections. He did not seek to show the people how they should vote, so much as to teach them elemental principles. He was the oracle, the sage, the teacher,–not the politician.

In the popular assemblies–whether for the discussion of political truths or those which bear on literature, education, history, finance, or industrial pursuits–Mr. Webster was pre-eminent. What audiences were ever more enthusiastic than those that gathered to hear his wisdom and eloquence in public halls or in the open air? It is true that in his later years he lost much of his wonderful personal magnetism, and did not rise to public expectation except on great occasions; but in middle life, in the earlier part of his congressional career, he had no peer as a popular orator. Edward Everett, on some occasions, was his equal, so far as manner and words were concerned; but, on the whole, even in his grandest efforts, Everett was cold compared with Webster in his palmy days. He never touched the heart and reason as did Webster; although it must be conceded that Everett was a great rhetorician, and was master of many of the graces of oratory.

The speeches and orations of Webster were not only weighty in matter, but were wonderful for their style,–so clear, so simple, so direct, that everybody could understand him. He rarely attempted to express more than one thought in a single sentence; so that his sentences never wearied an audience, being always logical and precise, not involved and long and complicated, like the periods of Chalmers and Choate and so many of the English orators. It was only in his grand perorations that he was Ciceronian. He despised purely extemporary efforts; he did not believe in them. He admits somewhere that he never could make a good speech without careful preparation. The principles embodied in his famous reply to Colonel Hayne of South Carolina, in the debate in the Senate on the right of “nullification,” had lain brooding in his mind for eighteen months. To a young minister he said, There is no such thing as extemporaneous acquisition.

Webster’s speeches are likely to live for their style alone, outside their truths, like those of Cicero and Demosthenes, like the histories of Voltaire and Macaulay, like the essays of Pascal and Rousseau; and they will live, not only for both style and matter, but for the exalted patriotism which burns in them from first to last, for those sentiments which consecrate cherished institutions. How nobly he recognizes Christianity as the bulwark of national prosperity! How delightfully he presents the endearments of home, the certitudes of friendship, the peace of agricultural life, the repose of all industrial pursuits, however humble and obscure! It was this fervid patriotism, this public recognition of what is purest in human life, and exalted in aspirations, and profound in experience,–teaching the value of our privileges and the glory of our institutions,–which gave such effect to his eloquence, and endeared him to the hearts of the people until he opposed their passions. If we read any of these speeches, extending over thirty years, we shall find everywhere the same consistent spirit of liberty, of union, of conciliation, the same moral wisdom, the same insight into great truths, the same recognition of what is sacred, the same repose on what is permanent, the same faith in the expanding glories of this great nation which he loved with all his heart. In all his speeches one cannot find a sentence which insults the consecrated sentiments of religion or patriotism. He never casts a fling at Christianity; he never utters a sarcasm in reference to revealed truths; he never flippantly aspires to be wiser than Moses or Paul in reference to theological dogmas. “Ah, my friends,” said he, in 1825, “let us remember that it is only religion and morals and knowledge that can make men respectable and happy under any form of government; that no government is respectable which is not just; that without unspotted purity of public faith, without sacred public principle, fidelity, and honor, no mere form of government, no machinery of laws, can give dignity to political society.”

Thus did he discourse in those proud days when he was accepted as a national idol and a national benefactor,–those days of triumph and of victory, when the people gathered around him as they gather around a successful general. Ah! how they thronged to the spot where he was expected to speak,–as the Scotch people thronged to Edinboro’ and Glasgow to hear Gladstone:–

“And when they saw his chariot but appear,

Did they not make an universal shout,

That Tiber trembled underneath her banks

To hear the replication of their sounds

Made in her concave shores?”

But it is time that I allude to those great services which Webster rendered to his country when he was a member of Congress,–services that can never be forgotten, and which made him a national benefactor.

There were three classes of subjects on which his genius pre-eminently shone,–questions of finance, the development of American industries, and the defence of the Constitution.

As early as 1815, Mr. Webster acquired a national reputation by his speech on the proposition to establish a national bank, which he opposed, since it was to be relieved from the necessity of redeeming its notes in specie. This was at the close of the war with Great Britain, when the country was poor, business prostrated, and the finances disordered. To relieve this pressure, many wanted an inflated paper currency, which should stimulate trade. But all this Mr. Webster opposed, as certain to add to the evils it was designed to cure. He would have a bank, indeed, but he insisted it should be established on sound financial principles, with notes redeemable in gold and silver. And he brought a great array of facts to show the certain and utter failure of a system of banking operations which disregarded the fundamental financial laws. He maintained that an inflated currency produced only temporary and illusive benefits. Nor did he believe in hopes which were not sustained by experience. “Banks,” said he, “are not revenue. They may afford facilities for its collection and distribution, but they cannot be sources of national income, which must flow from deeper fountains. Whatever bank-notes are not convertible into gold and silver, at the will of the holder, become of less value than gold and silver. No solidity of funds, no confidence in banking operations, has ever enabled them to keep up their paper to the value of gold and silver any longer than they paid gold and silver on demand.” Similar sentiments he advanced, in 1816, in his speech on the legal currency, and also in 1832, when he said that a disordered currency is one of the greatest of political evils,–fatal to industry, frugality, and economy. “It fosters the spirit of speculation and extravagance. It is the most effectual of inventions to fertilize the rich man’s field by the sweat of the poor man’s brow.” In these days, when principles of finance are better understood, these remarks may seem like platitudes; but they were not so fifty or sixty years ago, for then they had the force of new truth, although even then they were the result of political wisdom, based on knowledge and experience; and his views were adopted, for he appealed to reason.

Webster’s financial speeches are very calm, like the papers of Hamilton and Jay in “The Federalist,” but as interesting and persuasive as those of Gladstone, the greatest finance-minister of modern times. They are plain, simple, direct, without much attempt at rhetoric. He spoke like a great lawyer to a bench of judges. The solidity and soundness of his views made him greatly respected, and were remarkable in a young man of thirty-four. The subsequent financial history of the country shows that he was prophetic. All his predictions have come to pass. What is more marked in our history than the extravagance and speculation attending the expansion of paper money irredeemable in gold and silver? What misery and disappointment have resulted from inflated values! It was doubtless necessary to do without gold and silver in our life-and-death struggle with the South; but it was nevertheless a misfortune, seen in the gambling operations and the wild fever of speculation which attended the immense issue of paper money after the war. The bubble was sure to burst, sooner or later, like John Law’s Mississippi scheme in the time of Louis XV. How many thousands thought themselves rich, in New York and Chicago, in fact everywhere, when they were really poor,–as any man is poor when his house or farm is not worth the mortgage. As soon as we returned to gold and silver, or it was known we should return to them, then all values shrunk, and even many a successful merchant found he was really no richer than he was before the war. It had been easy to secure heavy mortgages on inflated values, and also to get a great interest on investments; but when these mortgages and investments shrank to what they were really worth, the holders of them became embarrassed and impoverished. The fit of commercial intoxication was succeeded by depression and unhappiness, and the moral evils of inflated values were greater than the financial, since of all demoralizing things the spirit of speculation and gambling brings, at last, the most dismal train of disappointments and miseries. Inflation and uncertainty in values, whether in stocks or real estate, alternating with the return of prosperity, seem to have marked the commercial and financial history of this country during the last fifty years, more than that of any other nation under the sun, and given rise to the spirit of extravagant speculations, both disgraceful and ruinous.

Equally remarkable were Mr. Webster’s speeches on tariffs and protective industries. He here seemed to borrow from Alexander Hamilton, who is the father of our protective system. Here he co-operated with Henry Clay; and the result of his eloquence and wisdom on those great principles of political economy was the adherence to a policy–against great opposition–which built up New England and did not impoverish the West. Where would the towns of Lowell, Manchester, and Lawrence have been without the aid extended to manufacturing interests? They made the nation comparatively independent of other nations; they enriched the country, even as manufactures enriched Great Britain and France. What would England be if it were only an agricultural country? It would have been impossible to establish manufactures of textile fabrics, without protection. Without aid from governments, this branch of American industry would have had no chance to contend with the cheap labor of European artisans. I do not believe in cheap labor. I do not believe in reducing intelligent people to the condition of animals. I would give them the chance to rise; and they cannot rise if they are doomed to labor for a mere pittance. The more wages men can get for honest labor, the better is the condition of the whole country. Withdraw protection from infant industries, and either they perish, or those who work in them sink to the condition of the laboring classes of Europe. Nor do I believe it is a good thing for a nation to have all its eggs in one basket. I would not make this country exclusively agricultural because we have boundless fields and can raise corn cheap, any more than I would recommend a Minnesota farmer to raise nothing but wheat. Insects and mildews and unexpected heats may blast a whole harvest, and the farmer has nothing to fall back upon. He may make more money, for a time, by raising wheat exclusively; but he impoverishes his farm. He should raise cattle and sheep and grass and vegetables, as well as wheat or corn. Then he is more independent and more intelligent, even as a nation is by various industries, which call out all kinds of talent.

I know that this is a controverted point. Everything is controverted in political economy. There is scarcely a question which is settled in its whole range of subjects; and I know that many intellectual and enlightened men are in favor of what they call free-trade, especially professors in colleges. But there is no such thing as free-trade, strictly, in any nation, or in the history of nations. No nation legislates for universal humanity on philanthropic principles; it legislates for itself. There is no country where there are not high duties on some things, not even England. No nation can be governed on abstract principles and in disregard of its necessities. When it was for the interest of England to remove duties on corn, in order that manufactures might be stimulated, they took off duties on corn, because the laboring-classes in the mills had to be fed. Agricultural interests gave way, for a time, to manufacturing interests, because the wealth of the country was based on them rather than on lands, and because landlords did not anticipate that bread-stuffs brought from this country would interfere with the value of their rents. But England, with all her proud and selfish boasts about free-trade, may yet have to take a retrograde course, like France and Prussia, or her landed interests may be imperilled. The English aristocracy, who rule the country, cannot afford to have the value of their lands reduced one-half, for those lands are so heavily mortgaged that such a reduction of value would ruin them; nor will they like to be forced to raise vegetables rather than wheat, and turn themselves into market-gardeners instead of great proprietors. The landlords of Great Britain may yet demand protection for themselves, and, as they control Parliament, they will look out for themselves by enacting measures of protection, unless they are intimidated by the people who demand cheap bread, or unless they submit to revolution. It is eternal equity and wisdom that the weak should be protected. There may be industries strong enough now to dispense with protection; but unless they are assisted when they are feeble, they will cease to exist at all. Take our shipping, for instance, with foreign ports,–it is not merely crippled, it is almost annihilated. Is it desirable to cut off that great arm of national strength? Shall we march on to our destiny, blind and lame and halt? What will we do if England and other countries shall find it necessary to protect themselves from impoverishment, and reintroduce duties on bread-stuffs high enough to make the culture of wheat profitable? Where then will our farmers find a market for their superfluous corn, except to those engaged in industries which we should crush by removing protection?

I maintain that Mr. Webster, in defending our various industries with so much ability, for the benefit of the nation on the whole, rendered very important services, even as Hamilton and Clay did; although the solid South, wishing cheap labor, and engaged exclusively in agriculture, was opposed to him. The independent South would have established free-trade,–as Mr. Calhoun advocated, and as any enlightened statesman would advocate, when any interest can stand alone and defy competition, as was the case with the manufactures of Great Britain fifty years ago. The interests of the South and those of the North, under the institution of slavery, were not identical; indeed, they had been in fierce opposition for more than fifty years. Mr. Webster was, in his arguments on tariffs and cognate questions, the champion of the North, as Mr. Calhoun was of the South; and this opposition and antagonism gave great force to Webster’s eloquence at this time. His sentences are short, interrogative, idiomatic. He is intensely in earnest. He grapples with sophistries and scatters them to the winds; both reason and passion vivify him.

This was the period of Webster’s greatest popularity, as the defender of Northern industries. This made him the idol of the merchants and manufacturers of New England. He made them rich; no wonder they made him presents. They ought, in gratitude, to have paid his debts over and over again. What if he did, in straitened circumstances, accept their aid? They owed to him more than he owed to them; and with all their favor and bounty Webster remained poor. He was never a rich man, but always an embarrassed man, because he had expensive tastes, like Cicero at Rome and Bacon in England. This, truly, was not to his credit; it was a flaw in his character; it involved him in debt, created enemies, and injured his reputation. It may have lessened his independence, and it certainly impaired his dignity. But there were also patriotic motives which prompted him, and which kept him poor. Had he devoted his great talents exclusively to the law, he might have been rich; but he gave his time to his country.

His greatest services to his country, however, were as the defender of the Constitution. Here he soared to the highest rank of political fame. Here he was a statesman, having in view the interests of the whole country. He never was what we call a politician. He never was such a miserable creature as that. I mean a mere politician, whose calling is the meanest a man can follow, since it seeks only spoils, and is a perpetual deception, incompatible with all dignity and independence, whose only watchword is success.

Not such was Webster. He was too proud and too dignified for that form of degradation; and he perhaps sacrificed his popularity to his intellectual dignity, and the glorious consciousness of being a national benefactor,–as a real statesman seeks to be, and is, when he falls back on the elemental principles of justice and morality, like a late Premier of England, one of the most conscientious statesmen that ever controlled the destinies of a nation. Webster, like Burke, was haughty, austere, and brave; but such a man is not likely to remain the favorite of the people, who prefer an Alcibiades to a Cato, except in great crises, when they look to a man who can save them, and whom they can forget.

I cannot enumerate the magnificent bursts of eloquence which electrified the whole country when Webster stood out as the defender of the Constitution, when he combated secession and defended the Union. How noble and gigantic he was when he answered the aspersions of the Southern orators,–great men as they were,–and elaborately showed that the Union meant something more than a league of sovereign States! The great leaders of secession were overthrown in a contest which they courted, and in which they expected victory. His reply to Hayne is, perhaps, the most masterly speech in American political history. It is one of the immortal orations of the world, extorting praise and admiration from Americans and foreigners alike. In his various encounters with Hayne, McDuffee, and Calhoun, he taught the principles of political union to the rising generation. He produced those convictions which sustained the North in its subsequent contest to preserve the integrity of the Nation. There can be no estimate of the services he rendered to the country by those grand and patriotic efforts. But for these, the people might have succumbed to the sophistries of Calhoun; for he was almost as great a giant as Webster, and was more faultless in his private life. He had an immense influence; he ruled the whole South; he made it solid. The speeches of Webster in the Senate made him the oracle of the North. He was not only the great champion of the North, and of Northern interests, but he was the teacher of the whole country. He expounded the principles of the Constitution,–that this great country is one, to be forever united in all its parts; that its stars and stripes were to float over every city and fortress in the land, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the river St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, and “bearing for their motto no such miserable interrogatory as, What are all these worth? nor those other words of delusion and folly, Liberty first and Union afterwards; but that other sentiment, dear to every American heart, Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

It was after his memorable speech in reply to Hayne that I saw Webster for the first time. I was a boy in college, and he had come to visit it; and well do I remember the unbounded admiration, yea, the veneration, felt for him by every young man in that college and throughout the town,–indeed, throughout the whole North, for he was the pride and glory of the land. It was then that they called him godlike, looking like an Olympian statue, or one of the creations of Michael Angelo when he wished to represent majesty and dignity and power in repose,–the most commanding human presence ever seen in the Capitol at Washington.

When we recall those patriotic and noble speeches which were read and admired by every merchant and farmer and lawyer in the country, and by which he produced great convictions and taught great lessons, we cannot but wonder why his glory was dimmed, and he was pulled down from his pedestal, and became no longer an idol. It is affirmed by many that it was his famous 7th of March speech which killed him, which disappointed his friends and alienated his constituents. I am therefore compelled to say something about that speech, and of his history at that time.

Mr. Webster was doubtless an ambitious man. He aspired to the presidency. And why not? It is and will be a great dignity, such as ought to be conferred on great ability and patriotism. Was he not able and patriotic? Had he not rendered great services? Was he not universally admired for his genius and experience and wisdom? Who was more prominent than he, among the statesmen of the country, or more thoroughly fitted to fulfil the duties of that high office? Was it not natural that he should have aspired to be one of the successors of Washington and Adams and Jefferson? He comprehended the honor and the dignity of that office. He did not seek it in order to divide its spoils, or to reward his friends; but he did wish to secure the highest prize that could be won by political services; he did desire to receive the highest honor in the gift of the people, even as Cicero sought the consulate at Rome; he did believe himself capable of representing the country in its most exacting position. It is nothing against a man that he is ambitious, provided his ambition is lofty. Most of the illustrious men of history have been ambitious,–Cromwell, Pitt, Thiers, Guizot, Bismarck,–but ambitious to be useful to their country, as well as to receive its highest rewards. Webster failed to reach the position he desired, because of his enemies, and, possibly, from jealousy of his towering height,–just as Clay failed, and Aaron Burr, and Alexander Hamilton, and Stephen Douglas, and William H. Seward. The politicians, who control the people, prefer men in the presidential chair whom they think they can manage and use, not those to whom they will be forced to succumb. Webster was not a man to be controlled or used, and so the politicians rejected him. This he deeply felt, and even resented. His failure saddened his latter days and embittered his soul, although he was too proud to make loud complaints.

I grant he did not here show magnanimity. He thought that the presidency should be given to the ablest and most experienced statesman. He did not appear to see that this proud position is too commanding to be bestowed except for the most exalted services, and such services as attract the common eye, especially in war. Presidents in so great a country as this reign, like the old feudal kings, by the grace of God. They are selected by divine Providence, as David was from the sheepfold. No American, however great his genius, except the successful warrior, can ever hope to climb to this dizzy height, unless personal ambition is lost sight of in public services. This is wisely ordered, to defeat unscrupulous ambition. It is only in England that a man can rise to supreme power by force of genius, since he is selected virtually by his peers, and not by the popular voice. He who leads Parliament is the real king of England for the time, since Parliament is omnipotent. Had Webster been an Englishman, and as powerful in the House of Commons as he was in Congress at one time, he might have been prime minister. But he could not be president of the United States, although the presidential power is much inferior to that exercised by an English premier. It is the dignity of the office, not its power, which constitutes the value of the presidency. And Webster loved dignity even more than power.

In order to arrive at this coveted office,–although its duties probably would have been irksome,–it is possible that he sought to conciliate the South and win the favor of Southern leaders. But I do not believe he ever sought to win their favor by any abandonment of his former principles, or by any treachery to the cause he had espoused. Yet it is this of which he has been accused by his enemies,–many of those enemies his former friends. The real cause of this estrangement, and of all the accusations against him, was this,–he did not sympathize with the Abolition party; he was not prepared to embark in a crusade against slavery, the basal institution of the South. He did not like slavery; but he knew it to be an institution which the Constitution, of which he was the great defender, had accepted,–accepted as a compromise, in those dark days which tried men’s souls. Many of the famous statesmen who deliberated in that venerated hall in Philadelphia also disliked and detested slavery; but they could not have had a constitution, they could not have had a united country, unless that institution was acknowledged and guaranteed. So they accepted it as the lesser evil. They made a compromise, and the Constitution was signed. Now, everybody knows that the Abolitionists of the North, about the year 1833, attacked slavery, although it was guaranteed by the Constitution; attacked it, not as an evil merely, but as a sin; attacked it, by virtue of a higher law than constitutional provision. And as an evil, as a stain on our country, as an insult to the virtue and intelligence of the age, as a crime against humanity, these people of the North declared that slavery ought to be swept away. Mr. Webster, as well as Mr. Fillmore, Mr. Lincoln, Mr. Everett, and many other acknowledged patriots, was for letting slavery alone, as an evil too great to be removed without war; which, moreover, could not be removed without an infringement on what the South considered as its rights. He was for conciliation, in order to preserve the Constitution as well as the Union. The Abolitionists were violent in their denunciations. And although it took many years to permeate the North with their leaven, they were in earnest; and under persecutions and mobs and ostracism and contempt they persevered until they created a terrible public opinion. The South had early taken the alarm, and in order to protect their peculiar and favorite institution, had at various times attempted to extend it into newly acquired territories where it did not exist, claiming the protection of the Constitution. Mr. Webster was one of their foremost opponents in this, contesting their right to do it under the Constitution. But in 1848 the Antislavery opinion at the North crystallized in a political organization,–the Free-Soil Party; and on the other hand the South proposed to abrogate the Missouri Compromise of 1820 as an offset to the admission of California as a free State, and at the same time asked in further concession the passage of the Fugitive Slave Bill; and, in anticipation of failing to get these, threatened secession, which of course meant war.

It was at this crisis that Mr. Webster delivered his celebrated 7th of March speech,–in many respects his greatest,–in which he advocated conciliation and adherence to the Constitution, but which was represented to support Southern interests, which all his life he had opposed; and more, to advocate these interests, in order to secure Southern votes for the presidency. Some of the rich and influential men of Boston who disliked Webster for other reasons,–for he used to snub them, even after they had lent him money,–made the most they could of that speech, to alienate the people. The Abolitionists, at last hostile to Mr. Webster, who stood in their way and would not adopt their dictation or advice, also bitterly denounced this speech, until it finally came to be regarded by the common people, few of whom ever read it, as a very unpatriotic production, entirely at variance with the views that Webster formerly advanced; and they forsook him.

Now, what is the real gist and spirit of that speech? The passions which agitated the country when it was delivered have passed away, and not only can we now calmly criticise it, but people will listen to the criticism with all the attention it deserves.

It is my opinion, shared by Peter Harvey and other friends of Mr. Webster, that in no speech he ever made are patriotic and Union sentiments more fully avowed. Said he, with fiery emphasis:–

“I hear with distress and anguish the word ‘secession.’ Secession! peaceable secession! Sir, your eyes and mine are never destined to see that miracle. The dismemberment of this great country without convulsion! The breaking up the fountains of the great deep without ruffling the surface! There can be no such thing as peaceable secession. It is an utter impossibility. Is this great Constitution, under which we live, to be melted and thawed away by secession, as the snows on the mountains are melted away under the influence of the vernal sun? No, sir; I see as plainly as the sun in the heavens what that disruption must produce. I see it must produce war.”

“Peaceable secession! peaceable secession! What would be the result? Where is the line to be drawn? What States are to secede? What is to remain American? What am I to be? Am I to be an American no longer,–a sectional man, a local man, a separatist, with no country in common? Heaven forbid! Where is the flag of the Union to remain? Where is the eagle still to tower? What is to become of the army? What is to become of the navy? What is to become of the public lands? How is each of the thirty States to defend itself? Will you cut the Mississippi in two, leaving free States on its branches and slave States at its mouth? Can any one suppose that this population on its banks can be severed by a line that divides them from the territory of a foreign and alien government, down somewhere,–the Lord knows where,–upon the lower branches of the Mississippi? Sir, I dislike to pursue this subject. I have utter disgust for it. I would rather hear of national blasts and mildews and pestilence and famine, than hear gentlemen talk about secession. To break up this great government! To dismember this glorious country! To astonish Europe with an act of folly, such as Europe for two centuries has never beheld in any government! No, sir; such talk is enough to make the bones of Andrew Jackson turn round in his coffin.”

Now, what are we to think of these sentiments, drawn from the 7th of March speech, so disgracefully misrepresented by the politicians and the fanatics? Do they sound like bidding for Southern votes? Can any Union sentiments be stronger? Can anything be more decided or more patriotic? He warns, he entreats, he predicts like a prophet. He proves that secession is incompatible with national existence; he sees nothing in it but war. And of all things he dreaded and hated, it was war. He knew what war meant. He knew that a civil war would be the direst calamity. He would ward it off. He would be conciliating. He would take away the excuse of war, by adhering to the Constitution,–the written Constitution which our fathers framed, and which has been the admiration of the world, under which we have advanced to prosperity and glory as no nation ever before advanced.

But a large class regarded the Constitution as unsound, in some respects a wicked Constitution, since it recognized slavery as an institution. By “the higher law,” they would sweep slavery away, perhaps by moral means, but by endless agitations, until it was destroyed. Mr. Webster, I confess, did not like those agitations, since he knew they would end in war. He had a great insight, such as few people had at that time. But his prophetic insight was just what a large class of people did not like, especially in his own State. He uttered disagreeable truths,–as all prophets do,–and they took up stones to stone him,–to stone him for the bravest act of his whole life, in which a transcendent wisdom appeared, and which will be duly honored when the truth shall be seen.

The fact was, at that time Mr. Webster seemed to be a croaker, a Jeremiah, as Burke at one time seemed to his generation, when he denounced the recklessness of the French Revolution. Very few people at the North dreamed of war. It was never supposed that the Southern leaders would actually become rebels. And they, on the other hand, never dreamed that the North would rise up solidly and put them down. And if war were to happen, it was supposed that it would be brief. Even so great and sagacious a statesman as Seward thought this. The South thought that it could easily whip the Yankees; and the North thought that it could suppress a Southern rebellion in six weeks. Both sides miscalculated. And so, in spite of warnings, the nation drifted into war; but as it turned out in the end it seems a providential event, –the way God took to break up slavery, the root and source of all our sectional animosities; a terrible but apparently necessary catastrophe, since more than a million of brave men perished, and more than five thousand millions of dollars were spent. Had the North been wise, it would have compensated the South for its slaves. Had the South been wise, it would have accepted the compensation and set them free, But it was not to be. That issue could only be settled by the most terrible contest of modern times.

I will not dwell on that war, which Webster predicted and dreaded. I only wish to show that it was not for want of patriotism that he became unpopular, but because he did not fall in with the prevailing passions of the day, or with the public sentiment of the North in reference to slavery, not as to its evils and wickedness, but as to the way in which it was to be opposed. The great reforms of England, since the accession of William III., have been effected by using constitutional means,–not violence, not revolution, not war; but by an appeal to reason and intelligence and justice. No reforms in any nation have been greater and more glorious than those of the nineteenth century,–all effected by constitutional methods. Mr. Webster vainly attempted constitutional means. He was a lawyer. He reverenced the Constitution, with all its compromises. He would observe the law of contracts. Yet no man in the nation was more impatient than he at the threats of secession. He foretold that secession would lead to war. And if Mr. Webster had lived to see the war of which he had such anxious prescience, I firmly believe that he would have marched under the banner of the North with patriotism equal to any man. He would have been where Mr. Everett was. One of his own sons was slain in that war. He was not a Northern man with Southern principles; his whole life attested his Northern principles. There never was a time when he was not hated and mistrusted by the Southern leaders. It is not a proof that he was Southern in his sympathies because he was not an Abolitionist; and by an Abolitionist I mean what was meant thirty years ago,–one who was unscrupulously bent on removing slavery by any means, good or bad; since slavery, in his eyes, was a malum per se, not a misfortune, an evil, a sin, but a crime to be washed out by the besom of destruction.

Mr. Webster did not sympathize with these extreme views. He was not a reformer; but that does not show that he was unpatriotic, or a Southern man in his heart. “The higher law,” to him, was the fulfilment of a contract; the maintenance of promises made in good faith, whether those promises were wise or foolish; the observance of laws so long as they were laws. There was, undeniably, a great evil and shame to be removed, but he was not responsible for it; and he left that evil in the hands of Him who said, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay,”–as He did repay in four years’ devastations, miseries, and calamities, and these so awful, so unexpected, so ill-prepared for, that a thoughtful and kind-hearted person, in view of them, will weep rather than rejoice; for it is not pleasant to witness chastisements and punishments, even if necessary and just, unless the people who suffer are fiends and incarnate devils, as very few men are. Human nature is about the same everywhere, and individuals and nations peculiarly sinful are generally made so by their surroundings and circumstances. The reckless people of frontier mining districts are not naturally worse than adventurers in New York or Philadelphia; nor is any vulgar and ignorant man, in any part of the country, suddenly made rich, probably any coarser in his pleasures, or more sensual in his appearance, or more profane in his language, than was Vitellius, or Heliogabalus, or Otho, on an imperial throne.

But even suppose Mr. Webster, in the decline of his life, intoxicated by his magnificent position or led astray by ambition, made serious political errors. What then? All great men have made errors, both in judgment and in morals,–Caesar, when he crossed the Rubicon; Theodosius, when he slaughtered the citizens of Thessalonica; Luther, when he quarrelled with Zwingli; Henry IV., when he stooped at Canossa; Elizabeth, when she executed Mary Stuart; Cromwell, when he bequeathed absolute power to his son; Bacon, when he took bribes; Napoleon, when he divorced Josephine; Hamilton, when he fought Burr. The sun itself passes through eclipses, as it gives light to the bodies which revolve around it. Even David and Peter stumbled. Because Webster professed to know as much of the interests of the country as the shoemakers of Lynn, and refused to be instructed in his political duties by Garrison and Wendell Phillips, does he deserve eternal reprobation? Because he opposed the public sentiments of his constituents on one point, when perhaps they were right, is he to be hurled from his lofty pedestal? Are all his services to be forgotten because he did not lift up his trumpet voice in favor of immediate emancipation? And even suppose he sought to conciliate the South when the South was preparing for rebellion,–is peace-making such a dreadful thing? Go still farther: suppose he wished to conciliate the South in order to get Southern support for the presidency–which I grant he wanted, and possibly sought,–is he to be unforgiven, and his name to be blasted, and he held up to the rising generation as a fallen man? Does a man fall hopelessly because he stumbles? Is a man to be dethroned because he is not perfect? When was Webster’s vote ever bought and sold? Who ever sat with more dignity in the councils of the nation? Would he have voted for “back pay”? Would he have bought a seat in the Senate, even if he had been as rich as a bonanza king?

Consider how few errors Webster really committed in a public career of nearly forty years. Consider the beneficence and wisdom of the measures which he generally advocated, and which would have been lost but for his eloquence and power. Consider the greatness and lustre of his congressional career on the whole. Who has proved a greater benefactor to this nation, on the floor of Congress, than he? I do not wish to eulogize, still less to whitewash, so great a man, but only to render simple justice to his memory and deeds. The time has come to lift the veil which for thirty years has concealed his noble political services. The time has come to cry shame on those boys who mocked a prophet, and said, “Go up, thou bald-head!”–although no bears were found to devour them. The time has come for this nation to bury the old slanders of an exciting political warfare, and render thanks for the services performed by the greatest intellectual giant of the past generation,–services rendered not on the floor of the Senate alone, not in the national legislature for thirty years, but in one of the great offices of State, when he made a treaty with England which saved us from an entangling war. The Ashburton treaty is the brightest gem in the coronet with which he should be crowned. It was the proudest day in Webster’s life when Rufus Choate announced to him one evening that the Senate had confirmed the treaty. It was not when he closed his magnificent argument in behalf of Dartmouth College, not when he addressed the intelligence of New England at Bunker Hill, not when he demolished Governor Hayne, not when he sat on the woolsack with Lord Brougham, not when he was entertained by Louis Philippe, that the proudest emotions swelled in his bosom, but when he learned that he had prevented a war with England,–for he knew that England and America could not afford to fight; that it would be a fight where gain is loss and glory is shame.

At last, worn out with labor and disease, and perhaps embittered by disappointment, and saddened to see the increasing tendency to elevate little men to power,–the “grasshoppers, who make the field ring with their importunate chinks, while the great cattle chew the cud and are silent,”–Webster died at Marshfield, Oct. 24, 1852, at seventy years of age. At the time he was Secretary of State. He died in the consolations of a religion in which he believed, surrounded with loving friends; and even his enemies felt that a great man in Israel had fallen. Nothing then was said of his defects, for great defects he had,–a towering intellectual pride like Chatham, an austerity like Gladstone, passions like those of Mirabeau, extravagance like that of Cicero, indifference to pecuniary obligations, like Pitt and Fox and Sheridan; but these were overbalanced by the warmth of his affections for his faithful friends, simplicity of manners and taste, courteous treatment of opponents, dignity of character, kindness to the poor, hospitality, enjoyment of rural scenes and sports, profound religious instincts, devotion to what he deemed the welfare of his country, independence of opinions and boldness in asserting them at any hazard and against all opposition, and unbounded contempt of all lies and shams and tricks. These traits will make his memory dear to all who knew him. And as Florence, too late, repented of her ingratitude to Dante, and appointed her most learned men to expound the “Divine Comedy” when he was dead, so will the writings of Webster be more and more a study among lawyers and statesmen. His fame will spread, and grow wider and greater, like that of Bacon and Burke, and of other benefactors of mankind; and his ideas will not pass away until the glorious fabric of American institutions, whose foundations were laid by God-fearing people, shall be utterly destroyed, and the Capitol, where his noblest efforts were made, shall become a mass of broken and prostrate columns beneath the débris of the nation’s ruin! No, not then shall they perish, even if such gloomy changes are possible, any more than the genius of Cicero has faded among the ruins of the Eternal City; but they shall shine upon the most distant works of man, since they are drawn from the wisdom of all preceding generations, and are based on those principles which underlie all possible civilizations!

Authorities.

The Works of Daniel Webster, in eight octavo volumes, including his speeches, addresses, orations, and legal arguments; Life of Daniel Webster, by G.T. Curtis; Private Correspondence, edited by F. Webster; Private Life, by C. Lanman; C.W. March’s Reminiscences of Congress; Peter Harvey’s Reminiscences and Anecdotes; Edward Everett’s Oration on the Unveiling of the Statue in Boston; R.C. Winthrop and Evarts, on the same occasion in New York; Contemporaneous Lives of Clay, Calhoun, and Benton; the great Oration on Webster by Rufus Choate at Dartmouth College; J. Barnard’s Life and Character of Daniel Webster; E.P. Whipple’s Essay on Webster; Eulogies on the Death of Webster, especially those by G.S. Hillard, L. Woods, A. Taft, R.D. Hitchcock, and Theodore Parker, also Addresses and Orations on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Webster’s Birth, too numerous to mention,—especially the address of Senator Bayard at Dartmouth College. The complete and exhaustive Life of Webster is yet to be written, although the most prominent of his contemporaries have had something to say.

John C. Calhoun : The Slavery Question

John Lord – Beacon Lights of History, Volume XII : American Founders