George Eliot : Woman as Novelist – Beacon Lights of History, Volume VII : Great Women by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume VII : Great Women

Héloïse : Love

Joan of Arc : Heroic Women

Saint Theresa : Religious Enthusiasm

Madame de Maintenon : The Political Woman

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

Madame Récamier : The Woman of Society

Madame de Staël : Woman in Literature

Hannah More : Education of Woman

George Eliot : Woman as Novelist

Beacon Lights of History, Volume VII : Great Women

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Notable eras of modern civilization

Nineteenth Century, the age of novelists

Scott, Fielding, Dickens, Thackeray

Bulwer; women novelists

Charlotte Brontë, Harriet Beecher Stowe, George Eliot

Early life of Marian Evans

Appearance, education, and acquirements

Change in religious views; German translations; Continental travel

Westminster Review; literary and scientific men

Her alliance with George Henry Lewes

Her life with him

Literary labors

First work of fiction, “Amos Barton,” with criticism upon

her qualities as a novelist, illustrated by the story

“Mr. Gilfils Love Story”

“Adam Bede”

“The Mill on the Floss”

“Silas Marner”

“Romola”

“Felix Holt”

“Middlemarch”

“Daniel Deronda”

“Theophrastus Such”

General characteristics of George Eliot

Death of Mr. Lewes; her marriage with Mr. Cross

Lofty position of George Eliot in literature

Religious views and philosophical opinions

Her failure as a teacher of morals

Regret at her abandonment of Christianity

George Eliot : Woman as Novelist

A.D. 1819-1880.

Since the dawn of modern civilization, every age has been marked by some new development of genius or energy. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries we notice Gothic architecture, the rise of universities, the scholastic philosophy, and a general interest in metaphysical inquiries. The fourteenth century witnessed chivalric heroism, courts of love, tournaments, and amorous poetry. In the fifteenth century we see the revival of classical literature and Grecian art. The sixteenth century was a period of reform, theological discussions, and warfare with Romanism. In the seventeenth century came contests for civil and religious liberty, and discussions on the theological questions which had agitated the Fathers of the Church. The eighteenth century was marked by the speculations of philosophers and political economists, ending in revolution. The nineteenth century has been distinguished for scientific discoveries and inventions directed to practical and utilitarian ends, and a wonderful development in the literature of fiction. It is the age of novelists, as the fifteenth century was the age of painters. Everybody now reads novels,–bishops, statesmen, judges, scholars, as well as young men and women. The shelves of libraries groan with the weight of novels of every description,–novels sensational, novels sentimental, novels historical, novels philosophical, novels social, and novels which discuss every subject under the sun. Novelists aim to be teachers in ethics, philosophy, politics, religion, and art; and they are rapidly supplanting lecturers and clergymen as the guides of men, accepting no rivals but editors and reviewers.

This extraordinary literary movement was started by Sir Walter Scott, who made a revolution in novel-writing, introducing a new style, freeing romances from bad taste, vulgarity, insipidity, and false sentiment. He painted life and Nature without exaggerations, avoided interminable scenes of love-making, and gave a picture of society in present and past times so fresh, so vivid, so natural, so charming, and so true, and all with such inimitable humor, that he still reigns without a peer in his peculiar domain. He is as rich in humor as Fielding, without his coarseness; as inventive as Swift, without his bitterness; as moral as Richardson, without his tediousness. He did not aim to teach ethics or political economy directly, although he did not disguise his opinions. His chief end was to please and instruct at the same time, stimulating the mind through the imagination rather than the reason; so healthful that fastidious parents made an exception of his novels among all others that had ever been written, and encouraged the young to read them. Sir Walter Scott took off the ban which religious people had imposed on novel-reading.

Then came Dickens, amazingly popular, with his grotesque descriptions of life, his exaggerations, his impossible characters and improbable incidents: yet so genial in sympathies, so rich in humor, so indignant at wrongs, so broad in his humanity, that everybody loved to read him, although his learning was small and his culture superficial.

Greatly superior to him as an artist and a thinker was Thackeray, whose fame has been steadily increasing,–the greatest master of satire in English literature, and one of the truest painters of social life that any age has produced; not so much admired by women as by men; accurate in his delineation of character, though sometimes bitter and fierce; felicitous in plot, teaching lessons in morality, unveiling shams and hypocrisy, contemptuous of all fools and quacks, yet sad in his reflections on human life.

In the brilliant constellation of which Dickens and Thackeray were the greater lights was Bulwer Lytton,–versatile; subjective in genius; sentimental, and yet not sensational; reflective, yet not always sound in morals; learned in general literature, but a charlatan in scientific knowledge; worldly in his spirit, but not a pagan; an inquisitive student, seeking to penetrate the mysteries of Nature as well as to paint characters and events in other times; and leaving a higher moral impression when he was old than when he was young.

Among the lesser lights, yet real stars, that have blazed in this generation are Reade, Kingsley, Black, James, Trollope, Cooper, Howells, Wallace, and a multitude of others, in France and Germany as well as England and America, to say nothing of the thousands who have aspired and failed as artists, yet who have succeeded in securing readers and in making money.

And what shall I say of the host of female novelists which this age has produced,–women who have inundated the land with productions both good and bad; mostly feeble, penetrating the cottages of the poor rather than the palaces of the rich, and making the fortunes of magazines and news-vendors, from Maine to California? But there are three women novelists, writing in English, standing out in this group of mediocrity, who have earned a just and wide fame,–Charlotte Bronté, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Marian Evans, who goes by the name of George Eliot.

It is the last of these remarkable women whom it is my object to discuss, and who burst upon the literary world as a star whose light has been constantly increasing since she first appeared. She takes rank with Dickens, Thackeray, and Bulwer, and some place her higher even than Sir Walter Scott. Her fame is prodigious, and it is a glory to her sex; indeed, she is an intellectual phenomenon. No woman ever received such universal fame as a genius except, perhaps, Madame de Staël; or as an artist, if we except Madame Dudevant, who also bore a nom de plume,–Georges Sand. She did not become immediately popular, but the critics from the first perceived her remarkable gifts and predicted her ultimate success. For vivid description of natural scenery and rural English life, minute analysis of character, and psychological insight she has never been surpassed by men; while for learning and profundity she has never been equalled by women,–a deep, serious, sad writer, without vanity or egotism or pretension; a great but not always sound teacher, who, by common consent and prediction, will live and rank among the classical authors in English literature.

Marian Evans was born in Warwickshire, about twenty miles from Stratford-on-Avon,–the county of Shakspeare, one of the most fertile and beautiful in England, whose parks and lawns and hedges and picturesque cottages, with their gardens and flowers and thatched roofs, present to the eye a perpetual charm. Her father, of Welsh descent, was originally a carpenter, but became, by his sturdy honesty, ability, and abiding sense of duty, land agent to Sir Roger Newdigate of Arbury Hall. Mr. Evans’s sterling character probably furnished the model for Adam Bede and Caleb Garth.

Sprung from humble ranks, but from conscientious and religious parents, who appreciated the advantage of education, Miss Evans was allowed to make the best of her circumstances. We have few details of her early life on which we can accurately rely. She was not an egotist, and did not leave an autobiography like Trollope, or reminiscences like Carlyle; but she has probably portrayed herself, in her early aspirations, as Madame de Staël did, in the characters she has created. The less we know about the personalities of very distinguished geniuses, the better it is for their fame. Shakspeare might not seem so great to us if we knew his peculiarities and infirmities as we know those of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Carlyle; only such a downright honest and good man as Dr. Johnson can stand the severe scrutiny of after times and “destructive criticism.”

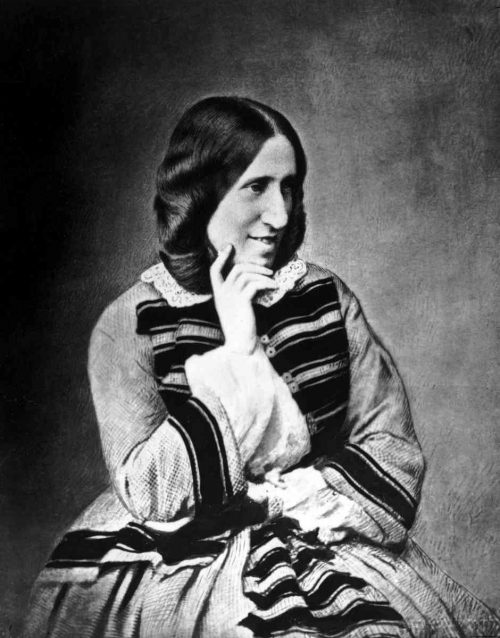

It would appear that Miss Evans was sent to a school in Nuneaton before she was ten, and afterwards to a school in Coventry, kept by two excellent Methodist ladies,–the Misses Franklin,–whose lives and teachings enabled her to delineate Dinah Morris. As a school-girl we are told that she had the manners and appearance of a woman. Her hair was pale brown, worn in ringlets; her figure was slight, her head massive, her mouth large, her jaw square, her complexion pale, her eyes gray-blue, and her voice rich and musical. She lost her mother at sixteen, when she most needed maternal counsels, and afterwards lived alone with her father until 1841, when they removed to Foleshill, near Coventry. She was educated in the doctrines of the Low or Evangelical Church, which are those of Calvin,–although her Calvinism was early modified by the Arminian views of Wesley. At twelve she taught a class in a Sunday-school; at twenty she wrote poetry, as most bright girls do. The head-master of the grammar school in Coventry taught her Greek and Latin, while Signor Brizzi gave her lessons in Italian, French, and German; she also played on the piano with great skill. Her learning and accomplishments were so unusual, and gave such indication of talent, that she was received as a friend in the house of Mr. Charles Bray, of Coventry, a wealthy ribbon-merchant, where she saw many eminent literary men of the progressive school, among whom were James Anthony Froude and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

At what period the change in her religious views took place I have been unable to ascertain,–probably between the ages of twenty-one and twenty-five, by which time she had become a remarkably well-educated woman, of great conversational powers, interesting because of her intelligence, brightness, and sensibility, but not for her personal beauty. In fact, she was not merely homely, she was even ugly; though many admirers saw great beauty in her eyes and expression when her countenance was lighted up. She was unobtrusive and modest, and retired within herself.

At this period she translated from the German the “Life of Jesus,” by Strauss, Feuerbach’s “Essence of Christianity,” and one of Spinoza’s works. Why should a young woman have selected such books to translate? How far the writings of rationalistic and atheistic philosophers affected her own views we cannot tell; but at this time her progressive and advanced opinions irritated and grieved her father, so that, as we are told, he treated her with intolerant harshness. With all her paganism, however, she retained the sense of duty, and was devoted in her attentions to her father until he died, in 1849. She then travelled on the Continent with the Brays, seeing most of the countries of Europe, and studying their languages, manners, and institutions. She resided longest in a boarding-house near Geneva, amid scenes renowned by the labors of Gibbon, Voltaire, and Madame de Staël, in sight of the Alps, absorbed in the theories of St. Simon and Proudhon,–a believer in the necessary progress of the race as the result of evolution rather than of revelation or revolution.

Miss Evans returned to England about the year 1857,–the year of the Great Exhibition,–and soon after became sub-editor of the “Westminster Review,” at one time edited by John Stuart Mill, but then in charge of John Chapman, the proprietor, at whose house, in the Strand, she boarded. There she met a large circle of literary and scientific men of the ultra-liberal, radical school, those who looked upon themselves as the more advanced thinkers of the age, whose aim was to destroy belief in supernaturalism and inspiration; among whom were John Stuart Mill, Francis Newman, Herbert Spencer, James Anthony Froude, G.H. Lewes, John A. Roebuck, and Harriet Martineau,–dreary theorists, mistrusted and disliked equally by the old Whigs and Tories, high-churchmen, and evangelical Dissenters; clever thinkers and learned doubters, but arrogant, discontented, and defiant.

It was then that the friendly attachment between Miss Evans and Mr. Lewes began, which ripened into love and ended in a scandal. Mr. Lewes was as homely as Wilkes, and was three years older than Miss Evans,–a very bright, witty, versatile, learned, and accomplished man; a brilliant talker, novelist, playwright, biographer, actor, essayist, and historian, whose “Life of Goethe” is still the acknowledged authority in Germany itself, as Carlyle’s “Frederic the Great” is also regarded. But his fame has since been eclipsed by that of the woman he pretended to call his wife, and with whom (his legal wife being still alive) he lived in open defiance of the seventh Commandment and the social customs of England for twenty years. This unfortunate connection, which saddened the whole subsequent life of Miss Evans, and tinged all her writings with the gall of her soul, excluded her from that high conventional society which it has been the aim of most ambitious women to enter. But this exclusion was not, perhaps, so great an annoyance to Miss Evans as it would have been to Hannah More, since she was not fitted to shine in general society, especially if frivolous, and preferred to talk with authors, artists, actors, and musical geniuses, rather than with prejudiced, pleasure-seeking, idle patricians, who had such attractions for Addison, Pope, Mackintosh, and other lights of literature, who unconsciously encouraged that idolatry of rank and wealth which is one of the most uninteresting traits of the English nation. Nor would those fashionable people, whom the world calls “great,” have seen much to attract them in a homely and unconventional woman whose views were discrepant with the established social and religious institutions of the land. A class that would not tolerate such a genius as Carlyle, would not have admired Marian Evans, even if the stern etiquette of English life had not excluded her from envied and coveted réunions; and she herself, doubtless, preferred to them the brilliant society which assembled in Mr. Chapman’s parlors to discuss those philosophical and political theories of which Comte was regarded as the high-priest, and his positivism the essence of all progressive wisdom.

How far the gloomy materialism and superficial rationalism of Lewes may have affected the opinions of Miss Evans we cannot tell. He was her teacher and constant companion, and she passed as his wife; so it is probable that he strengthened in her mind that dreary pessimism which appeared in her later writings. Certain it is that she paid the penalty of violating a fundamental moral law, in the neglect of those women whose society she could have adorned, and possibly in the silent reproaches of conscience, which she portrayed so vividly in the characters of those heroines who struggled ineffectually in the conflict between duty and passion. True, she accepted the penalty without complaint, and labored to the end of her days, with masculine strength, to enforce a life of duty and self-renunciation on her readers,–to live at least for the good of humanity. Nor did she court notoriety, like Georges Sand, who was as indifferent to reproach as she was to shame. Miss Evans led a quiet, studious, unobtrusive life with the man she loved, sympathetic in her intercourse with congenial friends, and devoted to domestic duties. And Mr. Lewes himself relieved her from many irksome details, that she might be free to prosecute her intense literary labors.

In this lecture on George Eliot I gladly would have omitted all allusion to a mistake which impairs our respect for this great woman. But defects cannot be unnoticed in an honest delineation of character; and no candid biographers, from those who described the lives of Abraham and David, to those who have portrayed the characters of Queen Elizabeth and Oliver Cromwell, have sought to conceal the moral defects of their subjects.

Aside from the translations already mentioned, the first literary efforts of Miss Evans were her articles in the “Westminster Review,” a heavy quarterly, established to advocate philosophical radicalism. In this Review appeared from her pen the article on Carlyle’s “Life of Sterling,” “Madame de la Sablière,” “Evangelical Teachings,” “Heine,” “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” “The Natural History of German Life,” “Worldliness and Unworldliness,”–all powerfully written, but with a vein of bitter sarcasm in reference to the teachers of those doctrines which she fancied she had outgrown. Her connection with the “Review” closed in 1853, when she left Mr. Chapman’s home and retired to a small house in Cambridge Terrace, Hyde Park, on a modest but independent income. In 1854 she revisited the Continent with Mr. Lewes, spending her time chiefly in Germany.

It was in 1857 that the first tales of Miss Evans were published in “Blackwood’s Magazine,” when she was thirty-eight, in the full maturity of her mind.

“The Sad Fortunes of Amos Barton” was the first of the series called “Scenes of Clerical Life” which appeared. Mr. Blackwood saw at once the great merit of the work, and although it was not calculated to arrest the attention of ordinary readers he published it, confident of its ultimate success. He did not know whether it was written by a man or by a woman; he only knew that he received it from the hand of Mr. Lewes, an author already well known as learned and brilliant. It is fortunate for a person in the conventional world of letters, as of society, to be well introduced.

This story, though gloomy in its tone, is fresh, unique, and interesting, and the style good, clear, vivid, strong. It opens with a beautiful description of an old-fashioned country church, with its high and square pews, in which the devout worshippers could not be seen by one another, nor even by the parson. This functionary went to church in top-boots, and, after his short sermon of platitudes, dined with the squire, and spent the remaining days of the week in hunting or fishing, and his evenings in playing cards, quietly drinking his ale, and smoking his pipe. But the hero of the story–Amos Barton–is a different sort of man from his worldly and easy rector. He is a churchman, and yet intensely evangelical and devoted to his humble duties,–on a salary of £80, with a large family and a sick wife. He is narrow, but truly religious and disinterested. The scene of the story is laid in a retired country village in the Midland Counties, at a time when the Evangelical movement was in full force in England, in the early part of last century, contemporaneous with the religious revivals of New England; when the bucolic villagers had little to talk about or interest them, before railways had changed the face of the country, or the people had been aroused to political discussions and reforms. The sorrows of the worthy clergyman centered in an indiscreet and in part unwilling hospitality which he gave to an artful, needy, pretentious, selfish woman, but beautiful and full of soft flatteries; which hospitality provoked scandal, and caused the poor man to be driven away to another parish. The tragic element of the story, however, centres in Mrs. Barton, who is an angel, radiant with moral beauty, affectionate, devoted, and uncomplaining, who dies at last from overwork and privations, and the cares of a large family of children.

There is no plot in this story, but its charm and power consist in a vivid description of common life, minute but not exaggerated, which enlists our sympathy with suffering and misfortune, deeply excites our interest in commonplace people living out their weary and monotonous existence. This was a new departure in fiction,–a novel without love-scenes or happy marriages or thrilling adventures or impossible catastrophes. But there is great pathos in this homely tale of sorrow; with no attempts at philosophizing, no digressions, no wearisome chapters that one wishes to skip, but all spontaneous, natural, free, showing reserved power,–the precious buds of promise destined to bloom in subsequent works, till the world should be filled with the aroma of its author’s genius. And there is also great humor in this clerical tale, of which the following is a specimen:–

“‘Eh, dear,’ said Mrs. Patten, falling back in her chair and lifting up her withered hands, ‘what would Mr. Gilfil say if he was worthy to know the changes as have come about in the church in these ten years? I don’t understand these new sort of doctrines. When Mr. Barton comes to see me he talks about my sins and my need of marcy. Now, Mr. Hackett, I’ve never been a sinner. From the first beginning, when I went into service, I’ve al’ys did my duty to my employers. I was as good a wife as any in the country, never aggravating my husband. The cheese-factor used to say that my cheeses was al’ys to be depended upon.'”

To describe clerical life was doubtless the aim which Miss Evans had in view in this and the two other tales which soon followed. In these, as indeed in all her novels, the clergy largely figure. She seems to be profoundly acquainted with the theological views of the different sects, as well as with the social habits of the different ministers. So far as we can detect her preference, it is for the Broad Church, or the “high-and-dry” clergy of the Church of England, especially those who were half squires and half parsons in districts where conservative opinions prevailed; for though she was a philosophical radical, she was reverential in her turn of mind, and clung to poetical and consecrated sentiments, always laying more stress on woman’s duties than on her rights.

The second of the Clerical series–“Mr. Gilfil’s Love Story”–is not so well told, nor is it so interesting as the first, besides being more after the fashion of ordinary stories. We miss in it the humor of good Mrs. Patten; nor are we drawn to the gin-and-water-drinking parson, although the description of his early unfortunate love is done with a powerful hand. The story throughout is sad and painful.

The last of the series, “Janet’s Repentance,” is, I think, the best. The hero is again a clergyman, an evangelical, whose life is one long succession of protracted martyrdoms,–an expiation to atone for the desertion of a girl whom he had loved and ruined while in college. Here we see, for the first time in George Eliot’s writings, that inexorable fate which pursues wrong-doing, and which so prominently stands out in all her novels. The singular thing is that she–at this time an advanced liberal–should have made the sinning young man, in the depth of his remorse, to find relief in that view of Christianity which is expounded by the Calvinists. But here she is faithful and true to the teaching of those by whom she was educated; and it is remarkable that her art enables her apparently to enter into the spiritual experiences of an evangelical curate with which she had no sympathy. She does not mock or deride, but seems to respect the religion which she had herself repudiated.

And the same truths which consoled the hard-working, self-denying curate are also made to redeem Janet herself, and secure for her a true repentance. This heroine of the story is the wife of a drunken, brutal village doctor, who dies of delirium tremens; she also is the slave of the same degrading habit which destroys her husband, but, unlike him, is a victim of remorse and shame. In her despair she seeks advice and consolation from the minister whom she had ridiculed and despised; and through him she is led to seek that divine aid which alone enables a confirmed drunkard to conquer what by mere force of will is an unconquerable habit. And here George Eliot–for that is the name she now goes by–is in accord with the profound experience of many.

The whole tale, though short, is a triumph of art and abounds with acute observations of human nature. It is a perfect picture of village life, with its gossip, its jealousies, its enmities, and its religious quarrels, showing on the part of the author an extraordinary knowledge of theological controversies and the religious movements of the early part of the nineteenth century. So vivid is her description of rural life, that the tale is really an historical painting, like the Dutch pictures of the seventeenth century, to be valued as an accurate delineation rather than a mere imaginary scene. Madonnas, saints, and such like pictures which fill the churches of Italy and Spain, works of the old masters, are now chiefly prized for their grace of form and richness of coloring,–exhibitions of ideal beauty, charming as creations, but not such as we see in real life; George Eliot’s novels, on the contrary, are not works of imagination, like the frescos in the Sistine Chapel, but copies of real life, like those of Wilkie and Teniers, which we value for their fidelity to Nature. And in regard to the passion of love, she does not portray it, as in the old-fashioned novels, leading to fortunate marriages with squires and baronets; but she generally dissects it, unravels it, and attempts to penetrate its mysteries,–a work decidedly more psychological than romantic or sentimental, and hence more interesting to scholars and thinkers than to ordinary readers, who delight in thrilling adventures and exciting narrations.

The “Scenes of Clerical Life” were followed the next year by “Adam Bede,” which created a great impression on the cultivated mind of England and America. It did not create what is called a “sensation.” I doubt if it was even popular with the generality of readers, nor was the sale rapid at first; but the critics saw that a new star of extraordinary brilliancy had arisen in the literary horizon. The unknown author entered, as she did in “Janet’s Repentance,” an entirely new field, with wonderful insight into the common life of uninteresting people, with a peculiar humor, great power of description, rare felicity of dialogue, and a deep undertone of serious and earnest reflection. And yet I confess, that when I first read “Adam Bede,” twenty-five years ago, I was not much interested, and I wondered why others were. It was not dramatic enough to excite me. Many parts of it were tedious. It seemed to me to be too much spun out, and its minuteness of detail wearied me. There was no great plot and no grand characters; nothing heroic, no rapidity of movement; nothing to keep me from laying the book down when the dinner-bell rang, or when the time came to go to bed. I did not then see the great artistic excellence of the book, and I did not care for a description of obscure people in the Midland Counties of England,–which, by the way, suggests a reason why “Adam Bede” cannot be appreciated by Americans as it is by the English people themselves, who every day see the characters described, and hear their dialect, and know their sorrows, and sympathize with their privations and labors. But after a closer and more critical study of the novel I have come to see merits that before escaped my eye. It is a study, a picture of humble English life, painted by the hand of a master, to be enjoyed most by people of critical discernment, and to be valued for its rare fidelity to Nature. It is of more true historical interest than many novels which are called historical,–even as the paintings of Rembrandt are more truly historical than those of Horace Vernet, since the former painted life as it really was in his day. Imaginative pictures are not those which are most prized by modern artists, or those pictures which make every woman look like an angel and every man like a hero,–like those of Gainsborough or Reynolds,–however flattering they may be to those who pay for them.

I need not dwell on characters so well known as those painted in “Adam Bede.” The hero is a painstaking, faithful journeyman carpenter, desirous of doing good work. Scotland and England abound in such men, and so did New England fifty years ago. This honest mechanic falls in love with a pretty but vain, empty, silly, selfish girl of his own class; but she had already fallen under the spell of the young squire of the village,–a good-natured fellow, of generous impulses, but essentially selfish and thoughtless, and utterly unable to cope with his duty. The carpenter, when he finds it out, gives vent to his wrath and jealousy, as is natural, and picks a quarrel with the squire and knocks him down,–an act of violence on the part of the inferior in rank not very common in England. The squire abandons his victim after ruining her character,–not an uncommon thing among young aristocrats,–and the girl strangely accepts the renewed attentions of her first lover, until the logic of events compels her to run away from home and become a vagrant. The tragic and interesting part of the novel is a vivid painting of the terrible sufferings of the ruined girl in her desolate wanderings, and of her trial for abandoning her infant child to death,–the inexorable law of fate driving the sinner into the realms of darkness and shame. The story closes with the prosaic marriage of Adam Bede to Dinah Morris,–a Methodist preacher, who falls in love with him instead of his more pious brother Seth, who adores her. But the love of Adam and Dinah for one another is more spiritualized than is common,–is very beautiful, indeed, showing how love’s divine elements can animate the human soul in all conditions of life. In the fervid spiritualism of Dinah’s love for Adam we are reminded of a Saint Theresa seeking to be united with her divine spouse. Dinah is a religious rhapsodist, seeking wisdom and guidance in prayer; and the divine will is in accordance with her desires. “My soul,” said she to Adam, “is so knit to yours that it is but a divided life if I live without you.”

The most amusing and finely-drawn character in this novel is a secondary one,–Mrs. Poyser,–but painted with a vividness which Scott never excelled, and with a wealth of humor which Fielding never equalled. It is the wit and humor which George Eliot has presented in this inimitable character which make the book so attractive to the English, who enjoy these more than the Americans,–the latter delighting rather in what is grotesque and extravagant, like the elaborate absurdities of “Mark Twain.” But this humor is more than that of a shrewd and thrifty English farmer’s wife; it belongs to human nature. We have seen such voluble sharp, sagacious, ironical, and worldly women among the farm-houses of New England, and heard them use language, when excited or indignant, equally idiomatic, though not particularly choice. Strike out the humor of this novel and the interest we are made to feel in commonplace people, and the story would not be a remarkable one.

“Adam Bede” was followed in a year by “The Mill on the Floss,” the scene of which is also laid in a country village, where are some well-to-do people, mostly vulgar and uninteresting. This novel is to me more powerful than the one which preceded it,–having more faults, perhaps, but presenting more striking characters. As usual with George Eliot, her plot in this story is poor, involving improbable incidents and catastrophes. She is always unfortunate in her attempts to extricate her heroes and heroines from entangling difficulties. Invention is not her forte; she is weak when she departs from realistic figures. She is strongest in what she has seen, not in what she imagines; and here she is the opposite of Dickens, who paints from imagination. There was never such a man as Pickwick or Barnaby Rudge. Sir Walter Scott created characters,–like Jeannie Deans,–but they are as true to life as Sir John Falstaff.

Maggie Tulliver is the heroine of this story, in whose intellectual developments George Eliot painted herself, as Madame De Staël describes her own restless soul-agitations in “Delphine” and “Corinne.” Nothing in fiction is more natural and life-like than the school-days of Maggie, when she goes fishing with her tyrannical brother, and when the two children quarrel and make up,–she, affectionate and yielding; he, fitful and overbearing. Many girls are tyrannized over by their brothers, who are often exacting, claiming the guardianship which belongs only to parents. But Maggie yields to her obstinate brother as well as to her unreasonable and vindictive father, governed by a sense of duty, until, with her rapid intellectual development and lofty aspiration, she breaks loose in a measure from their withering influence, though not from technical obligations. She almost loves Philip Wakem, the son of the lawyer who ruined her father; yet out of regard to family ties she refuses, while she does not yet repel, his love. But her real passion is for Stephen Gurst, who was betrothed to her cousin, and who returned Maggie’s love with intense fervor.

“Why did he love her? Curious fools, be still!

Is human love the fruit of human will?”

She knows she ought not to love this man, yet she combats her passion with poor success, allows herself to be compromised in her relations with him, and is only rescued by a supreme effort of self-renunciation,–a principle which runs through all George Eliot’s novels, in which we see the doctrines of Buddha rather than those of Paul, although at times they seem to run into each other. Maggie erred in not closing the gate of her heart inexorably, and in not resisting the sway of a purely “physiological law.” The vivid description of this sort of love, with its “strange agitations” and agonizing ecstasies, would have been denounced as immoral fifty years ago. The dénouement is an improbable catastrophe on a tidal river, in the rising floods of which Maggie and her brother are drowned,–a favorite way with the author in disposing of her heroes and heroines when she can no longer manage them.

The secondary characters of this novel are numerous, varied, and natural, and described with great felicity and humor. None of them are interesting people; in fact, most of them are very uninteresting,–vulgar, money-loving, material, purse-proud, selfish, such as are seen among those to whom money and worldly prosperity are everything, with no perception of what is lofty and disinterested, and on whom grand sentiments are lost,–yet kind-hearted in the main, and in the case of the Dobsons redeemed by a sort of family pride. The moral of the story is the usual one with George Eliot,–the conflict of duty with passion, and the inexorable fate which pursues the sinner. She brings out the power of conscience as forcibly as Hawthorne has done in his “Scarlet Letter.”

The “Mill on the Floss” was soon followed by “Silas Marner,” regarded by some as the gem of George Eliot’s novels, and which certainly–though pathetic and sad, as all her novels are–does not leave on the mind so mournful an impression, since in its outcome we see redemption. The principal character–the poor, neglected, forlorn weaver–emerges at length from the Everlasting Nay into the Everlasting Yea; and he emerges by the power of love,–love for a little child whom he has rescued from the snow, the storm, and death. Driven by injustice to a solitary life, to abject penury, to despair, the solitary miser, gloating over his gold pieces,–which he has saved by the hardest privation, and in which he trusts,–finds himself robbed, without redress or sympathy; but in the end he is consoled for his loss in the love he bestows on a helpless orphan, who returns it with the most noble disinterestedness, and lives to be his solace and his pride. Nothing more touching has ever been written by man or woman than this short story, as full of pathos as “Adam Bede” is full of humor.

What is remarkable in this story is that the plot is exactly similar to that of “Jermola the Potter,” the masterpiece of a famous Polish novelist,–a marvellous coincidence, or plagiarism, difficult to be explained. But Shakspeare, the most original of men, borrowed some of his plots from Italian writers; and Mirabeau appropriated the knowledge of men more learned than he, which by felicity of genius he made his own; and Webster, too, did the same thing. There is nothing new under the sun, except in the way of “putting things.”

After the publication of the various novels pertaining to the rural and humble life of England, with which George Eliot was so well acquainted, into which she entered with so much sympathy, and which she so marvellously portrayed, she took a new departure, entering a field with which she was not so well acquainted, and of which she could only learn through books. The result was “Romola,” the most ambitious, and in some respects the most remarkable, of all her works. It certainly is the most learned and elaborate. It is a philosophico-historical novel, the scene of which is laid in Florence at the time of Savonarola,–the period called the Renaissance, when art and literature were revived with great enthusiasm; a very interesting period, the glorious morning, as it were, of modern civilization.

This novel, the result of reading and reflection, necessarily called into exercise other faculties besides accurate observation,–even imagination and invention, for which she is not pre-eminently distinguished. In this novel, though interesting and instructive, we miss the humor and simplicity of the earlier works. It is overloaded with learning. Not one intelligent reader in a hundred has ever heard even the names of many of the eminent men to whom she alludes. It is full of digressions, and of reflections on scientific theories. Many of the chapters are dry and pedantic. It is too philosophical to be popular, too learned to be appreciated. As in some of her other stories, highly improbable events take place. The plot is not felicitous, and the ending is unsatisfactory. The Italian critics of the book are not, on the whole, complimentary. George Eliot essayed to do, with prodigious labor, what she had no special aptitude for. Carlyle in ten sentences would have made a more graphic picture of Savonarola. None of her historical characters stand out with the vividness with which Scott represented Queen Elizabeth and Mary, Queen of Scots, or with which even Bulwer painted Rienzi and the last of the Barons.

Critics do not admire historical novels, because they are neither history nor fiction. They mislead readers on important issues, and they are not so interesting as the masterpieces of Macaulay and Froude. Yet they have their uses. They give a superficial knowledge of great characters to those who will not read history. The field of history is too vast for ordinary people, who have no time for extensive reading even if they have the inclination.

The great historical personage whom George Eliot paints in “Romola” is Savonarola,–and I think faithfully, on the whole. In the main she coincides with Villani, the greatest authority. In some respects I should take issue with her. She makes the religion of the Florentine reformer to harmonize with her notions of self-renunciation. She makes him preach the “religion of humanity,” which was certainly not taught in his day. He preached duty, indeed, and appealed to conscience; but he preached duty to God rather than to man. The majesty of a personal God, fearful in judgment and as represented by the old Jewish prophets, was the great idea of Savonarola’s theology. His formula was something like this: “Punishment for sin is a divine judgment, not the effect of inexorable laws. Repentance is a necessity. Unless men repent of their sins, God will punish them. Unless Italy repents, it will be desolated by His vengeance.” Catholic theology, which he never departed from, has ever recognized the supreme allegiance of man to his Maker, because He demands it. Even among the Jesuits, with their corrupted theology, the motto emblazoned on their standard was, Ad majorem dei gloriam. But the great Dominican preacher is made by George Eliot to be “the spokesman of humanity made divine, not of Deity made human.” “Make your marriage vows,” said he to Romola, “an offering to the great work by which sin and sorrow are made to cease.”

But Savonarola is only a secondary character in the novel. He might as well have been left out altogether. The real hero and heroine are Romola and Tito; and they are identified with the life of the period, which is the Renaissance,–a movement more Pagan than Christian. These two characters may be called creations. Romola is an Italian woman, supposed to represent a learned and noble lady four hundred years ago. She has lofty purposes and aspirations; she is imbued with the philosophy of self-renunciation; her life is devoted to others,–first to her father, and then to humanity. But she is as cold as marble; she is the very reverse of Corinne. Even her love for Tito is made to vanish away on the first detection of his insincerity, although he is her husband. She becomes as hard and implacable as fate; and when she ceases to love her husband, she hates him and leaves him, and is only brought back by a sense of duty. Yet her hatred is incurable; and in her wretched disappointment she finds consolation only in a sort of stoicism. How far George Eliot’s notions of immortality are brought out in the spiritual experiences of Romola I do not know; but the immortality of Romola is not that which is brought to light by the gospel: it is a vague and indefinite sentiment kindred to that of Indian sages,–that we live hereafter only in our teachings or deeds; that we are absorbed in the universal whole; that our immortality is the living in the hearts and minds of men, not personally hereafter among the redeemed To quote her own fine thought,–

“Oh, may I join the choir invisible

In pulses stirred to generosity,

In deeds of daring rectitude, in scorn

For miserable aims that end in self,

In thoughts sublime that pierce the night like stars,

And, with their mild persistence, urge man’s search

To vaster issues!”

Tito is a more natural character, good-natured, kind-hearted, with generous impulses. He is interesting in spite of his faults; he is accomplished, versatile, and brilliant. But he is inherently selfish, and has no moral courage. He gradually, in his egotism, becomes utterly false and treacherous, though not an ordinary villain. He is the creature of circumstances. His weakness leads to falsehood, and falsehood ends in crime; which crime pursues him with unrelenting vengeance,–not the agonies of remorse, for he has no conscience, but the vindictive and persevering hatred of his foster father, whom he robbed. The vengeance of Baldassare is almost preternatural; it surpasses the wrath of Achilles and the malignity of Shylock. It is the wrath of a demon, from which there is no escape; it would be tragical if the subject of it were greater. Though Tito perishes in an improbable way, he is yet the victim of the inexorable law of human souls.

But if “Romola” has faults, it has remarkable excellences. In this book George Eliot aspires to be a teacher of ethics and philosophy. She is not humorous, but intensely serious and thoughtful. She sometimes discourses like Epictetus:–

“And so, my Lillo,” says she at the conclusion, “if you mean to act nobly, and seek to know the best things God has put within reach of man, you must learn to fix your mind on that end, and not on what will happen to you because of it. And remember, if you were to choose something lower, and make it the rule of your life to seek your own pleasure and escape what is disagreeable, calamity might come just the same; and it would be a calamity falling on a base mind,–which is the one form of sorrow that has no balm in it, and that may well make a man say, ‘It would have been better for me if I had never been born.'”

Three years elapsed between the publication of “Romola” and that of “Felix Holt,” which shows to what a strain the mind of George Eliot had been subjected in elaborating an historical novel. She now returns to her own peculiar field, in which her great successes had been made, and with which she was familiar; and yet even in her own field we miss now the genial humanity and inimitable humor of her earlier novels. In “Felix Holt” she deals with social and political problems in regard to which there is great difference of opinion; for the difficult questions of political economy have not yet been solved. Felix Holt is a political economist, but not a vulgar radical filled with discontent and envy. He is a mechanic, tolerably educated, and able to converse with intelligence on the projected reforms of the day, in cultivated language. He is high-minded and conscientious, but unpractical, and gets himself into difficulties, escaping penal servitude almost by miracle, for the crime of homicide. The heroine, Esther Lyon, is supposed to be the daughter of a Dissenting minister, who talks theology after the fashion of the divines of the seventeenth century; unknown to herself, however, she is really the daughter of the heir of large estates, and ultimately becomes acknowledged as such, but gives up wealth and social position to marry Felix Holt, who had made a vow of perpetual poverty. Such a self-renunciation is not common in England. Even a Paula would hardly have accepted such a lot; only one inspired with the philosophy of Marcus Aurelius would be capable of such a willing sacrifice,–very noble, but very improbable.

The most powerful part of the story is the description of the remorse which so often accompanies an illicit love, as painted in the proud, stately, stern, unbending, aristocratic Mrs. Transome. “Though youth has faded, and joy is dead, and love has turned to loathing, yet memory, like a relentless fury, pursues the gray-haired woman who hides within her breast a heavy load of shame and dread.” Illicit love is a common subject with George Eliot; and it is always represented as a mistake or crime, followed by a terrible retribution, sooner or later,–if not outwardly, at least inwardly, in the sorrows of a wounded and heavy-laden soul.

No one of George Eliot’s novels opens more beautifully than “Felix Holt,” though there is the usual disappointment of readers with the close. And probably no description of a rural district in the Midland Counties fifty years ago has ever been painted which equals in graphic power the opening chapter. The old coach turnpike, the roadside inns brilliant with polished tankards, the pretty bar-maids, the repartees of jocose hostlers, the mail-coach announced by the many blasts of the bugle, the green willows of the water-courses, the patient cart-horses, the full-uddered cows, the rich pastures, the picturesque milkmaids, the shepherd with his slouching walk, the laborer with his bread and bacon, the tidy kitchen-garden, the golden corn-ricks, the bushy hedgerows bright with the blossoms of the wild convolvulus, the comfortable parsonage, the old parish church with its ivy-mantled towers, the thatched cottage with double daisies and geraniums in the window-seats,–these and other details bring before our minds a rural glory which has passed away before the power of steam, and may never again return.

“Felix Holt” was published in 1866, and it was five years before “Middlemarch” appeared,–a very long novel, thought by some to be the best which George Eliot has written; read fifteen times, it is said, by the Prince of Wales. In this novel the author seems to have been ambitious to sustain her fame. She did not, like Trollope, dash off three novels a year, and all alike. She did not write mechanically, as a person grinds at a mill. Nor was she greedy of money, to be spent in running races with the rich. She was a conscientious writer from first to last. Yet “Middlemarch,” with all the labor spent upon it, has more faults than any of her preceding novels. It is as long as “The History of Sir Charles Grandison;” it has a miserable plot; it has many tedious chapters, and too many figures, and too much theorizing on social science. Rather than a story, it is a panorama of the doctors and clergymen and lawyers and business people who live in a provincial town, with their various prejudices and passions and avocations. It is not a cheerful picture of human life. We are brought to see an unusual number of misers, harpies, quacks, cheats, and hypocrites. There are but few interesting characters in it: Dorothea is the most so,–a very noble woman, but romantic, and making great mistakes. She desires to make herself useful to somebody, and marries a narrow, jealous, aristocratic pedant, who had spent his life in elaborate studies on a dry and worthless subject. Of course, she awakes from her delusion when she discovers what a small man, with great pretensions, her learned husband is; but she remains in her dreariness of soul a generous, virtuous, and dutiful woman. She does not desert her husband because she does not love him, or because he is uncongenial, but continues faithful to the end. Like Maggie Tulliver and Romola, she has lofty aspirations, but marries, after her husband’s death, a versatile, brilliant, shallow Bohemian, as ill-fitted for her serious nature as the dreary Casaubon himself.

Nor are we brought in sympathy with Lydgate, the fashionable doctor with grand aims, since he allows his whole scientific aspirations to be defeated by a selfish and extravagant wife. Rosamond Vincy is, however, one of the best drawn characters in fiction, such as we often see,–pretty, accomplished, clever, but incapable of making a sacrifice, secretly thwarting her husband, full of wretched complaints, utterly insincere, attractive perhaps to men, but despised by women. Caleb Garth is a second Adam Bede; and Mrs. Cadwallader, the aristocratic wife of the rector, is a second Mrs. Poyser in the glibness of her tongue and in the thriftiness of her ways. Mr. Bullstrode, the rich banker, is a character we unfortunately sometimes find in a large country town,–a man of varied charities, a pillar of the Church, but as full of cant as an egg is of meat; in fact, a hypocrite and a villain, ultimately exposed and punished.

The general impression left on the mind from reading “Middlemarch” is sad and discouraging. In it is brought out the blended stoicism, humanitarianism, Buddhism, and agnosticism of the author. She paints the “struggle of noble natures, struggling vainly against the currents of a poor kind of world, without trust in an invisible Rock higher than themselves to which they could entreat to be lifted up.”

In another five years George Eliot produced “Daniel Deronda,” the last and most unsatisfactory of her great novels, written in feeble health and with exhausted nervous energies, as she was passing through the shadows of the evening of her life. In this work she doubtless essayed to do her best; but she could not always surpass herself, any more than could Scott or Dickens. Nor is she to be judged by those productions which reveal her failing strength, but by those which were written in the fresh enthusiasm of a lofty soul. No one thinks the less of Milton because the “Paradise Regained” is not equal to the “Paradise Lost.” Many are the immortal poets who are now known only for two or three of their minor poems. It takes a Michael Angelo to paint his grandest frescos after reaching eighty years of age; or a Gladstone, to make his best speeches when past the age of seventy. Only people with a wonderful physique and unwasted mental forces can go on from conquering to conquer,–people, moreover, who have reserved their strength, and lived temperate and active lives.

Although “Daniel Deronda” is occasionally brilliant, and laboriously elaborated, still it is regarded generally by the critics as a failure. The long digression on the Jews is not artistic; and the subject itself is uninteresting, especially to the English, who have inveterate prejudices against the chosen people. The Hebrews, as they choose to call themselves, are doubtless a remarkable people, and have marvellously preserved their traditions and their customs. Some among them have arisen to the foremost rank in scholarship, statesmanship, and finance. They have entered, at different times, most of the cabinets of Europe, and have held important chairs in its greatest universities. But it was a Utopian dream that sent Daniel Deronda to the Orient to collect together the scattered members of his race. Nor are enthusiasts and proselytes often found among the Jews. We see talent, but not visionary dreamers. To the English they appear as peculiarly practical,–bent on making money, sensual in their pleasures, and only distinguished from the people around them by an extravagant love of jewelry and a proud and cynical rationalism. Yet in justice it must be confessed, that some of the most interesting people in the world are Jews.

In “Daniel Deronda” the cheerless philosophy of George Eliot is fully brought out. Mordecai, in his obscure and humble life, is a good representative of a patient sufferer, but “in his views and aspirations is a sort of Jewish Mazzini.” The hero of the story is Mordecai’s disciple, who has discovered his Hebrew origin, of which he is as proud as his aristocratic mother is ashamed The heroine is a spoiled woman of fashion, who makes the usual mistake of most of George Eliot’s heroines, in violating conscience and duty. She marries a man whom she knows to be inherently depraved and selfish; marries him for his money, and pays the usual penalty,–a life of silent wretchedness and secret sorrow and unavailing regret. But she is at last fortunately delivered by the accidental death of her detested husband,–by drowning, of course. Remorse in seeing her murderous wishes accomplished–though not by her own hand, but by pursuing fate–awakens a new life in her soul, and she is redeemed amid the throes of anguish and conscious guilt.

“Theophrastus Such,” the last work of George Eliot, is not a novel, but a series of character sketches, full of unusual bitterness and withering sarcasm. Thackeray never wrote anything so severe. It is one of the most cynical books ever written by man or woman. There is as much difference in tone and spirit between it and “Adam Bede,” as between “Proverbs” and “Ecclesiastes;” as between “Sartor Resartus” and the “Latter-Day Pamphlets.” And this difference is not more marked than the difference in style and language between this and her earlier novels. Critics have been unanimous in their admiration of the author’s style in “Silas Marner” and “The Mill on the Floss,”–so clear, direct, simple, natural; as faultless as Swift, Addison, and Goldsmith, those great masters of English prose, whose fame rests as much on their style as on their thoughts. In “Theophrastus Such,” on the contrary, as in some parts of “Daniel Deronda,” the sentences are long, involved, and often almost unintelligible.

In presenting the works of George Eliot, I have confined myself to her prose productions, since she is chiefly known by her novels. But she wrote poetry also, and some critics have seen considerable merit in it. Yet whatever merit it may have I must pass without notice. I turn from the criticism of her novels, as they successively appeared, to allude briefly to her closing days. Her health began to fail when she was writing “Middlemarch,” doubtless from her intense and continual studies, which were a severe strain on her nervous system. It would seem that she led a secluded life, rarely paying visits, but receiving at her house distinguished literary and scientific men. She was fond of travelling on the Continent, and of making short visits to the country. In conversation she is said to have been witty, tolerant, and sympathetic. Poetry, music, and art absorbed much of her attention. She read very little contemporaneous fiction, and seldom any criticisms on her own productions. For an unbeliever in historical Christianity, she had great reverence for all earnest Christian peculiarities, from Roman Catholic asceticism to Methodist fervor. In her own belief she came nearest to the positivism of Comte, although he was not so great an oracle to her as he was to Mr. Lewes, with whom twenty years were passed by her in congenial studies and labors. They were generally seen together at the opening night of a new play or the début of a famous singer or actor, and sometimes, within a limited circle, they attended a social or literary reunion.

In 1878 George Eliot lost the companion of her literary life. And yet two years afterward–at the age of fifty-nine–she surprised her friends by marrying John Walter Cross, a man much younger than herself. No one can fathom that mystery. But Mrs. Cross did not long enjoy the felicities of married life. In six months from her marriage, after a pleasant trip to the Continent, she took cold in attending a Sunday concert in London; and on the 22d of December, 1880, she passed away from earth to join her “choir invisible,” whose thoughts have enriched the world.

It is not extravagant to say that George Eliot left no living competitor equal to herself in the realm of fiction. I do not myself regard her as great a novelist as Scott or Thackeray; but critics generally place her second only to those great masters in this department of literature. How long her fame will last, who can tell? Admirers and rhetoricians say, “as long as the language in which her books are written.” She doubtless will live as long as any English novelist; but do those who amuse live like those who save? Will the witty sayings of Dickens be cherished like the almost inspired truths of Plato, of Bacon, of Burke? Nor is popularity a sure test of posthumous renown.

The question for us to settle is, not whether George Eliot as a writer is immortal, but whether she has rendered services that her country and mankind will value. She has undoubtedly added to the richness of English literature. She has deeply interested and instructed her generation. Thousands, and hundreds of thousands, owe to her a debt of gratitude for the enjoyment she has afforded them. How many an idle hour has she not beguiled! How many have felt the artistic delight she has given them, like those who have painted beautiful pictures! As already remarked, we read her descriptions of rural character and life as we survey the masterpieces of Hogarth and Wilkie.

It is for her delineation of character, and for profound psychological analysis, that her writings have permanent value. She is a faithful copyist of Nature. She recalls to our minds characters whom everybody of large experience has seen in his own village or town,–the conscientious clergyman, and the minister who preaches like a lecturer; the angel who lifts up, and the sorceress who pulls down. We recall the misers we have scorned, and the hypocrites whom we have detested. We see on her canvas the vulgar rich and the struggling poor, the pompous man of success and the broken-down man of misfortune; philanthropists and drunkards, lofty heroines and silly butterflies, benevolent doctors and smiling politicians, quacks and scoundrels and fools, mixed up with noble men and women whose aspirations are for a higher life; people of kind impulses and weak wills, of attractive personal beauty with meanness of mind and soul. We do not find exaggerated monsters of vice, or faultless models of virtue and wisdom: we see such people as live in every Christian community. True it is that the impression we receive of human life is not always pleasant; but who in any community can bear the severest scrutiny of neighbors? It is this fidelity to our poor humanity which tinges the novels of George Eliot with so deep a gloom.

But the sadness which creeps over us in view of human imperfection is nothing to that darkness which enters the soul when the peculiar philosophical or theological opinions of this gifted woman are insidiously but powerfully introduced. However great she was as a delineator of character, she is not an oracle as a moral teacher. She was steeped in the doctrines of modern agnosticism. She did not believe in a personal God, nor in His superintending providence, nor in immortality as brought to light in the gospel. There are some who do not accept historical Christianity, but are pervaded with its spirit. Even Carlyle, when he cast aside the miracles of Christ and his apostles as the honest delusions of their followers, was almost a Calvinist in his recognition of God as a sovereign power; and he abhorred the dreary materialism of Comte and Mill as much as he detested the shallow atheism of Diderot and Helvetius. But George Eliot went beyond Carlyle in disbelief. At times, especially in her poetry, she writes almost like a follower of Buddha. The individual soul is absorbed in the universal whole; future life has no certainty; hope in redemption is buried in a sepulchre; life in most cases is a futile struggle; the great problems of existence are invested with gloom as well as mystery. Thus she discourses like a Pagan. She would have us to believe that Theocritus was wiser than Pascal; that Marcus Aurelius was as good as Saint Paul.

Hence, as a teacher of morals and philosophy George Eliot is not of much account. We question the richness of any moral wisdom which is not in harmony with the truths that Christian people regard as fundamental, and which they believe will save the world. In some respects she has taught important lessons. She has illustrated the power of conscience and the sacredness of duty. She was a great preacher of the doctrine that “whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” She showed that those who do not check and control the first departure from virtue will, in nine cases out of ten, hopelessly fall.

These are great certitudes. But there are others which console and encourage as well as intimidate. The Te Domine Speravi of the dying Xavier on the desolate island of Sancian, pierced through the clouds of dreary blackness which enveloped the nations he sought to save. Christianity is full of promises of exultant joy, and its firmest believers are those whose lives are gilded with its divine radiance. Surely, it is not intellectual or religious narrowness which causes us to regret that so gifted a woman as George Eliot–so justly regarded as one of the greatest ornaments of modern literature–should have drifted away from the Rock which has resisted the storms and tempests of nearly two thousand years, and abandoned, if she did not scorn, the faith which has animated the great masters of thought from Augustine to Bossuet. “The stern mournfulness which is produced by most of her novels gives us the idea of one who does not know, or who has forgotten, that the stone was rolled away from the heart of the world on the morning when Christ arose from the tomb.”

Authorities.

Miss Blind’s Life of George Eliot. Mr. Cross’s Life of George Eliot, I regret to say, did not reach me until after the foregoing pages had gone to press. But as this lecture is criticism rather than history, the few additional facts that might have been gained would not be important; while, after tracing in that quasi-autobiography the development of her mental and moral nature, I see no reason to change my conclusions based on the outward facts of her life and on her works. The Nineteenth Century, ix.; London Quarterly Review, lvii. 40; Contemporary Review, xx. 29, 39; The National Review, xxxi. 23, 16; Blackwood’s Magazine, cxxix. 85-100, 112, 116, 103; Edinburgh Review, ex. 144, 124, 137, 150; Westminster Review, lxxi. 110, lxxxvi. 74, 80, 90, 112; Dublin Review, xlvii. 88, 89; Cornhill Magazine, xliii.; Atlantic Monthly, xxxviii. 18; Fortnightly Review, xxvi. 19; British Quarterly Review, lxiv. 57, 48, 45; International Review, iv. 10; Temple Bar Magazine, 49; Littell’s Living Age, cxlviii.; The North American Review, ciii. 116, 107; Quarterly Review, cxxxiv. 108; Macmillan’s Magazine, iii. 4; North British Review, xiv.