George IV : Toryism – Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

Mirabeau : The French Revolution

Edmund Burke : Political Morality

Napoleon Bonaparte : The French Empire

Prince Metternich : Conservatism

Chateaubriand : The Restoration and Fall of the Bourbons

George IV : Toryism

The Greek Revolution

Louis Philippe : The Citizen King

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Condition of England in 1815

The aristocracy

The House of Commons

The clergy

The courts of law

The middle classes

The working classes

Ministry of Lord Liverpool

Lord Castlereagh

George Canning

Mr. Perceval

Regency of the Prince of Wales

His scandalous private life

Caroline of Brunswick

Death of George III

Canning, Prime Minister

His great services

His death

His character

Popular agitations

Catholic association

Great political leaders

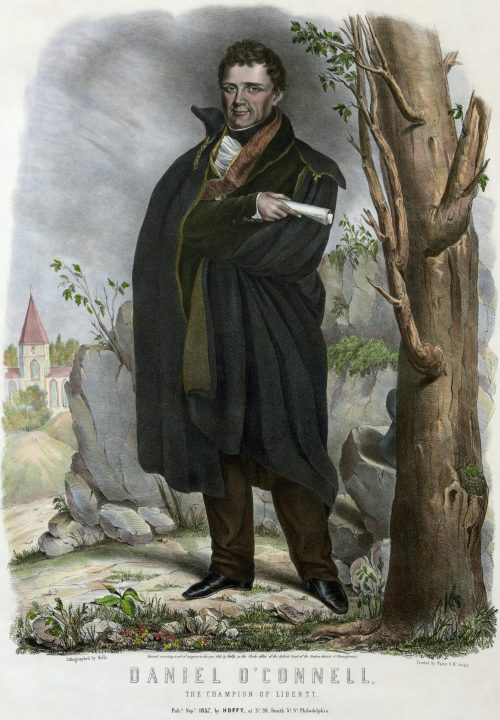

O’Connell

Duke of Wellington

Catholic emancipation

Latter days of George IV

His death

Brilliant constellation of great men

George IV : Toryism

1762-1830.

Where an intelligent and cultivated though superficial traveller to recount his impressions of England in 1815, when the Prince of Wales was regent of the kingdom and Lord Liverpool was prime minister, he probably would note his having been struck with the splendid life of the nobility (all great landed proprietors) in their palaces at London, and in their still more magnificent residences on their principal estates. He would have seen a lavish if not an unbounded expenditure, emblazoned and costly equipages, liveried servants without number, and all that wealth could purchase in the adornment of their homes. He would have seen a perpetual round of banquets, balls, concerts, receptions, and garden parties, to which only the élite of society were invited, all dressed in the extreme of fashion, blazing with jewels, and radiant with the smiles of prosperity. Among the lions of this gorgeous society he would have seen the most distinguished statesmen of the day, chiefly peers of the realm, with the blue ribbon across their shoulders, the diamond garter below their knees, and the heraldic star upon their breasts. Perhaps he might have met some rising orator, like Canning or Perceval, whose speeches were in every mouth,–men destined to the highest political honors, pets of highborn ladies for the brilliancy of their genius, the silvery tones of their voices, and the courtly elegance of their manners; Tories in their politics, and aristocrats in their sympathies.

The traveller, if admitted as a stranger to these grand assemblages, would have seen but few lawyers, except of the very highest distinction, perhaps here and there a bishop or a dean with the paraphernalia of clerical rank, but no physician, no artist, no man of science, no millionaire banker, no poet, no scholar, unless his fame had gone out to all the world. The brilliancy of the spectacle would have dazzled him, and he would unhesitatingly have pronounced those titled men and women to be the most fortunate, the most favored, and perhaps the most happy of all people on the face of the globe, since, added to the distinctions of rank and the pride of power, they had the means of purchasing all the pleasures known to civilization, and–more than all–held a secure social position, which no slander could reach and no hatred could affect.

Or if he followed these magnates to their country estates after the “season” had closed and Parliament was prorogued, he would have seen the palaces of these lordly proprietors of innumerable acres filled with a retinue of servants that would have called out the admiration of Cicero or Crassus,–all in imposing liveries, but with cringing manners,–and a crowd of aristocratic visitors, filling perhaps a hundred apartments, spending their time according to their individual inclinations; some in the magnificent library of the palace, some riding in the park, others fox-hunting with the hounds or shooting hares and partridges, others again flirting with ennuied ladies in the walks or boudoirs or gilded drawing-rooms,–but all meeting at dinner, in full dress, in the carved and decorated banqueting-hall, the sideboards of which groaned under the load of gold and silver plate of the rarest patterns and most expensive workmanship. Everywhere the eye would have rested on priceless pictures, rare tapestries, bronze and marble ornaments, sumptuous sofas and lounges, mirrors of Venetian glass, chandeliers, antique vases, bric-à-brac of every description brought from every corner of the world. The conversation of these titled aristocrats,–most of them educated at Oxford and Cambridge, cultivated by foreign travel, and versed in the literature of the day,–though full of prejudices, was generally interesting; while their manners, though cold and haughty, were easy, polished, courteous, and dignified. It is true, most of them would swear, and get drunk at their banquets; but their profanity was conventional rather than blasphemous, and they seldom got drunk till late in the evening, and then on wines older than their children, from the most famous vineyards of Europe. During the day they were able to attend to business, if they had any, and seldom drank anything stronger than ale and beer. Their breakfasts were light and their lunches simple. Living much in the open air, and fond of the pleasures of the chase, they were generally healthy and robust. The prevailing disease which crippled them was gout; but this was owing to champagne and burgundy rather than to brandy and turtle-soups, for at that time no Englishman of rank dreamed that he could dine without wine. William Pitt, it is said, found less than three bottles insufficient for his dinner, when he had been working hard.

Among them all there was great outward reverence for the Church, and few missed its services on Sundays, or failed to attend family prayers in their private chapels as conducted by their chaplains, among whom probably not a Dissenter could be found in the whole realm. Both Catholics and Dissenters were alike held in scornful contempt or indifference, and had inferior social rank. On the whole, these aristocrats were a decorous class of men, though narrow, bigoted, reserved, and proud, devoted to pleasure, idle, extravagant, and callous to the wrongs and miseries of the poor. They did not insult the people by arrogance or contumely, like the old Roman nobles; but they were not united to them by any other ties than such as a master would feel for his slaves; and as slaves are obsequious to their masters, and sometimes loyal, so the humbler classes (especially in the country) worshipped the ground on which these magnates walked. “How courteous the nobles are!” said a wealthy plebeian manufacturer to me once, at Manchester. “I was to show my mill to Lord Ducie, and as my carriage drove up I was about to mount the box with the coachman, but my lord most kindly told me to jump in.”

So much for the highest class of all in England, about the year 1815. Suppose the attention of the traveller were now turned to the legislative halls, in which public affairs were discussed, particularly to the House of Commons, supposed to represent the nation. He would have seen five or six hundred men, in plain attire, with their hats on, listless and inattentive, except when one of their leaders was making a telling speech against some measure proposed by the opposite party,–and nearly all measures were party measures. Who were these favored representatives? Nearly all of them were the sons or brothers or cousins or political friends of the class to which I have just alluded, with here and there a baronet or powerful county squire or eminent lawyer or wealthy manufacturer or princely banker, but all with aristocratic sympathies,–nearly all conservative, with a preponderance of Tories; scarcely a man without independent means, indifferent to all questions except such as affected party interests, and generally opposed to all movements which had in view the welfare of the middle classes, to which they could not be said to belong. They did not represent manufacturing towns nor the shopkeepers, still less the people in their rugged toils,–ignorant even when they could read and write. They represented the great landed interests of the country for the most part, and legislated for the interests of landlords and the gentry, the Established Church and the aristocratic universities,–indeed, for the wealthy and the great, not for the nation as a whole, except when great public dangers were imminent.

At that time, however, the traveller would have heard the most magnificent bursts of eloquence ever heard in Parliament,–speeches which are immortal, classical, beautiful, and electrifying. On the front benches was Canning, scarcely inferior to Pitt or Fox as an orator; stately, sarcastic, witty, rhetorical, musical, as full of genius as an egg is full of meat. There was Castlereagh,–not eloquent, but gifted, the honored plenipotentiary and negotiator at the Congress of Vienna; the friend of Metternich and the Czar Alexander; at that time perhaps the most influential of the ministers of state, the incarnation of aristocratic manners and ultra conservative principles. There was Peel, just rising to fame and power; wealthy, proud, and aristocratic, as conservative as Wellington himself, a Tory of the Tories. There were Perceval, the future prime minister, great both as lawyer and statesman; and Lord Palmerston, secretary of state for war. On the opposite benches sat Lord John Russell, timidly maturing schemes for parliamentary reform, lucid of thought, and in utterance clear as a bell. There, too, sat Henry Brougham, not yet famous, but a giant in debate, and overwhelming in his impetuous invectives. There were Romilly, the law reformer, and Tierney, Plunkett, and Huskisson (all great orators), and other eminent men whose names were on every tongue. The traveller, entranced by the power and eloquence of these leaders, could scarcely have failed to feel that the House of Commons was the most glorious assembly on earth, the incarnation of the highest political wisdom, the theatre and school of the noblest energies, worthy to instruct and guide the English nation, or any other nation in the world.

From the legislature we follow our traveller to the Church,–the Established Church of course, for non-conformist ministers, whatever their learning and oratorical gifts, ranked scarcely above shopkeepers and farmers, and were viewed by the aristocracy as leaders of sedition rather than preachers of righteousness. The higher dignitaries of the only church recognized by fashion and rank were peers of the realm, presidents of colleges, dons in the universities, bishops with an income of £10,000 a year or more, deans of cathedrals, prebendaries and archdeacons, who wore a distinctive dress from the other clergy. I need not say that they were the most aristocratic, cynical, bigoted, and intolerant of all the upper ranks in the social scale, though it must be confessed that they were generally men of learning and respectability, more versed, however, in the classics of Greece and Rome than in Saint Paul’s epistles, and with greater sympathy for the rich than for the poor, to whom the gospel was originally preached. The untitled clergy of the Church in their rural homes,–for the country and not the city was the paradise of rectors and curates, as of squires and men of leisure,–were also for the most part classical scholars and gentlemen, though some thought more of hunting and fishing than of the sermons they were to preach on Sundays. Nothing to the eye of a cultivated traveller was more fascinating than the homes of these country clergymen, rectories and parsonages as they were called,–concealed amid shrubberies, groves, and gardens, where flowers bloomed by the side of the ivy and myrtle, ever green and flourishing. They were not large but comfortable, abodes of plenty if not of luxury, freeholds which could not be taken away, suggestive of rest and repose; for the favored occupant of such a holding, supported by tithes, could neither be ejected nor turned out of his “living,” which he held for life, whether he preached well or poorly, whether he visited his flock or buried himself amid his books, whether he dined out with the squire or went up to town for amusement, whether he played lawn tennis in the afternoon with aristocratic ladies, or cards in the evening with gentlemen none too sober. He had an average stipend of £200 a year, equal to £400 in these times,–moderate, but sufficient for his own wants, if not for those of his wife and daughters, who pined of course for a more exciting life, and for richer dresses than he could afford to give them. His sermons, it must be confessed, were not very instructive, suggestive, or eloquent,–were, in fact, without point, delivered in a drawling monotone; but then his hearers were not used to oratorical displays or learned treatises in the pulpit, and were quite satisfied with the glorious liturgy, if well intoned, and pious chants from surpliced boys, if it happened to be a church rich and venerable in which they worshipped.

Not less imposing and impressive than the Church would the traveller have found the courts of law. The House of Lords was indeed, in a general sense, a legislative assembly, where the peers deliberated on the same subjects that occupied the attention of the Commons; but it was also the supreme judicial tribunal of the realm,–a great court of appeals of which only the law lords, ex-chancellors and judges, who were peers, were the real members, presided over by the lord chancellor, who also held court alone for the final decision of important equity questions. The other courts of justice were held by twenty-four judges, in different departments of the law, who presided in their scarlet robes in Westminster Hall, and who also held assizes in the different counties for the trial of criminals,–all men of great learning and personal dignity, who were held in awe, since they were the representatives of the king himself to decree judgments and punish offenders against the law. Even those barristers who pleaded at these tribunals quailed before the searching glance of these judges, who were the picked men of their great profession, whom no sophistry could deceive and no rhetoric could win,–men held in supreme honor for their exalted station as well as for their force of character and acknowledged abilities. In no other country were judges so well paid, so independent, so much feared, and so deserving of honors and dignities. And in no other country were judges armed with more power, nor were they more bland and courteous in their manners and more just in their decisions. It was something to be a judge in England.

Turning now from peers, legislators, judges, and bishops,–the men who composed the governing class,–all equally aristocratic and exclusive, let us with our traveller survey the middle class, who were neither rich nor poor, living by trade, chiefly shopkeepers, with a sprinkling of dissenting ministers, solicitors, surgeons, and manufacturers. Among these, the observer is captivated by the richness and splendor of their shops, over which were dark and dingy chambers used as residences by their plebeian occupants, except such as were rented as lodgings to visitors and men of means. These people of business were rarely ambitious of social distinction, for that was beyond their reach; but they lived comfortably, dined on roast beef and Yorkshire pudding on Sunday, with tolerable sherry or port to wash it down, went to church or chapel regularly in silk or broadcloth, were good citizens, had a horror of bailiffs, could converse on what was going on in trade and even in politics to a limited extent, and generally advocated progressive and liberal sentiments,–unless some of their relatives were employed in some way or other in noble houses, in which case their loyalty to the crown and admiration of rank were excessive and amusing. They read good books when they read at all, educated their children, some of whom became governesses, travelled a little in the summer, were hospitable to their limited circle of friends, were kind and obliging, put on no airs, and were on the whole useful and worthy people, if we can not call them “respectable members of society.” They were, perhaps, the happiest and most contented of all the various classes, since they were virtuous, frugal, industrious, and thought more of duties than they did of pleasures. These were the people who were soon to discuss rights rather than duties, and whom the reform movement was to turn into political enthusiasts.

Such was the bright side of the picture which a favored traveller would have seen at the close of the Napoleonic wars,–on the whole, one of external prosperity and grandeur, compared with most Continental countries; an envied civilization, the boast of liberty, for there was no regal despotism. The monarch could send no one to jail, or exile him, or cut off his head, except in accordance with law; and the laws could deprive no one of personal liberty without sufficient cause, determined by judicial tribunals.

And yet this splendid exterior was deceptive. The traveller saw only the rich or favored or well-to-do classes; there were toiling and suffering millions whom he did not see. Although the laws were made to favor the agricultural interests, yet there was distress among agricultural laborers; and the dearer the price of corn,–that is, the worse the harvests,–the more the landlords were enriched, and the more wretched were those who raised the crops. In times of scarcity, when harvests were poor, the quartern loaf sold sometimes for two shillings, when the laborer could earn on an average only six or seven shillings a week. Think of a family compelled to live on seven shillings a week, with what the wife and children could additionally earn! There was rent to pay, and coals and clothing to buy, to say nothing of a proper and varied food supply; yet all that the family could possibly earn would not pay for bread alone. And the condition of the laboring classes in the mines and the mills was still worse; for not half of them could get work at all, even at a shilling a day. The disbanding of half a million of soldiers, without any settled occupation, filled every village and hamlet with vagrants and vagabonds demoralized by war. During the war with France there had been a demand for every sort of manufactures; but the peace cut off this demand, and the factories were either closed or were running on half-time. Then there was the dreadful burden of taxation, direct and indirect, to pay the interest of a national debt swelled to the enormous amount of £800,000,000, and to meet the current expenses of the government, which were excessive and frequently unnecessary,–such as sinecures, pensions, and grants to the royal family. This debt pressed upon all classes alike, and prevented the use of all those luxuries which we now regard as necessities,–like sugar, tea, coffee, and even meat. There were import duties, almost prohibitory, on many articles which few could do without, and worst of all, on corn and all cereals. Without these it was possible for the laboring class to live, even when they earned only a shilling a day; but when these were retained to swell the income of that upper class whose glories and luxuries I have already mentioned, there was inevitable starvation.

To any kind of popular sorrow and misery, however, the government seemed indifferent; and this was followed of course by discontent and crime, riots and incendiary conflagrations, murders and highway robberies,–an incipient pandemonium, disgusting to see and horrible to think of. At the best, what dens of misery and filth and disease were the quarters of the poor, in city and country alike, especially in the coal districts and in manufacturing towns. And when these pallid, half-starved miners and operatives, begrimed with smoke and dirt, issued from their infernal hovels and gathered in crowds, threatening all sorts of violence, and dispersed only at the point of the bayonet, there was something to call out fear as well as compassion from those who lived upon their toils.

At last, good men became aroused at the injustice and wretchedness which filled every corner of the land, and sent up their petitions to Parliament for reform,–not for the mere alleviation of miseries, but for a reform in representation, so that men might be sent as legislators who would take some interest in the condition of the poor and oppressed. Yet even to these petitions the aristocratic Commons paid but little heed. The sigh of the mourner was unheard, and the tear of anguish was unnoticed by those who lived in their lordly palaces. What was desperate suffering and agitation for relief they called agrarian discontent and revolutionary excess, to be put down by the most vigorous measures the government could devise. O tempora! O mores! the Roman orator exclaimed in view of social evils which would bear no comparison with those that afflicted a large majority of the human beings who struggled for a miserable existence in the most lauded country in Europe. In their despair, well might they exclaim, “Who shall deliver us from the body of this death?”

I often wonder that the people of England were as patient and orderly as they were, under such aggravated misfortunes. In France the oppressed would probably have arisen in a burst of frenzy and wrath, and perhaps have unseated the monarch on his throne. But the English mobs erected no barricades, and used no other weapons than groans and expostulations. They did not demand rights, but bread; they were not agitators, but sufferers. Promises of relief disarmed them, and they sadly returned to their wretched homes to see no radical improvement in their condition. Their only remedy was patience, and patience without much hope. Nothing could really relieve them but returning prosperity, and that depended more on events which could not be foreseen than on legislation itself.

Such was the condition, in general terms, of high and low, rich and poor, in England in the year 1815, and I have now to show what occupied the attention of the government for the next fifteen years, during the reign of George IV. as regent and as king. But first let us take a brief review of the men prominent in the government.

Lord Liverpool was the prime minister of England for fifteen years, from 1812 (succeeding to Perceval upon the latter’s assassination) to 1827. He was a man of moderate abilities, but honest and patriotic; this chief merit was in the tact by which he kept together a cabinet of conflicting political sentiments; but he lived in comparatively quiet times, when everybody wanted rest and repose, and when he had only to combat domestic evils. The lord chancellor, Lord Eldon, had been seated on the woolsack from nearly the beginning of the century, and was the “keeper of the king’s conscience” for twenty-five years, enjoying his great office for a longer period than any other lord chancellor in English history. He was doubtless a very great lawyer and a man of remarkable sagacity and insight, but the narrowest and most bigoted of all the great men who controlled the destinies of the nation. He absolutely abhorred any change whatever and any kind of reform. He adhered to what was already established, and because it was established; therefore he was a good churchman and a most reliable Tory.

The most powerful man in the cabinet at this time, holding the second office in the government, that of foreign secretary, was Lord Castlereagh,–no very great scholar or orator or man of business, but an inveterate Tory, who played into the hands of all the despots of Europe, and who made captive more powerful minds than his own by the elegance of his manners, the charm of his conversation, and the intensity of his convictions. William Pitt never showed greater sagacity than when he bought the services of this gifted aristocrat (for he was then a Whig), and introduced him into Parliament. He was the most prominent minister of the crown until he died, directing foreign affairs with ability, but in the wrong direction,–the friend and ally of Metternich, Chateaubriand, Hardenberg, and the monarchs whom they represented.

But foremost in genius among the great statesmen of the day was George Canning, who, however, did not reach the summit of his ambition until the latter part of the reign of George IV. But after the death of Castlereagh in 1822, he was the leading spirit of the cabinet, holding the great office of foreign secretary, second in rank and power only to that of the premier. Although a Tory,–the follower and disciple of Pitt,–it was Canning who gave the first great blow to the narrow and selfish conservatism which marked the government of his day, and entered the first wedge which was to split the Tory ranks and inaugurate reform. For this he acquired the greatest popularity that any statesman in England ever enjoyed, if we except Fox and Pitt, and at the same time incurred the bitterest wrath which the Metternichs of the world have ever cherished toward the benefactors of mankind.

Canning was born in London, in the year 1770, in comparatively humble life,–his father being a dissipated and broken-down barrister, and his mother compelled by poverty to go upon the stage. But he had a wealthy relative who took the care of his education. In 1788 he entered Christ Church College, where he won the prize for the best Latin poem that Oxford had ever produced. After he had graduated with distinguished honors, he entered as a law student at Lincoln’s Inn; but before he wore the gown of a barrister Pitt had sought him out, as he had Castlereagh, having heard of his talents in debating societies. Pitt secured him a seat in Parliament, and Canning made his first speech on the 31st of January, 1794. The aid which he brought to the ministry secured his rapid advancement. In a year after his maiden speech he was made under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, at the age of twenty-five. On the death of Pitt, in 1806, when the Whigs for a short period came into power, Canning was the recognized leader of the opposition; and in 1807, when the Tories returned to power, he became foreign secretary in the ministry of the Duke of Portland, of which Mr. Perceval was the leading member. It was then that Canning seized the Danish fleet at Copenhagen, giving as his excuse for this bold and high-handed measure that Napoleon would have taken it if he had not. It was through his influence and that of Lord Castlereagh that Sir Arthur Wellesley, afterward the Duke of Wellington, was sent to Spain to conduct the Peninsular War.

On the retirement of the Duke of Portland as head of the government in 1809, Mr. Perceval became minister,–an event soon followed by the insanity of George III. and the entrance of Robert Peel into the House of Commons. In 1812 Mr. Perceval was assassinated, and the long ministry of Lord Liverpool began, supported by all the eloquence and influence of Canning, between whom and his chief a close friendship had existed since their college days. The foreign secretaryship was offered to Canning; but he, being comparatively poor, preferred the Lisbon embassy, on the large salary of £14,000. In 1814 he became president of the Board of Control, and remained in that office until he was appointed governor-general of India. On the death of Castlereagh (1822) by his own hand, Canning resumed the post of foreign secretary, and from that time was the master spirit of the government, leader of the House of Commons, the most powerful orator of his day, and the most popular man in England. He had now become more liberal, showing a sympathy with reform, acknowledging the independence of the South American colonies, and virtually breaking up the Holy Alliance by his disapprobation of the policy of the Congress of Vienna, which aimed at the total overthrow of liberty in Europe, and which (under the guidance of Metternich and with the support of Castlereagh) had already given Norway to Sweden, the duchy of Genoa to Sardinia, restored to the Pope his ancient possessions, and made Italy what it was before the French Revolution. The most mischievous thing which the Holy Alliance had in view was interference in the internal affairs of all the Continental States, under the guise of religion. England, under the leadership of Castlereagh, would have upheld this foreign interference of Russia, Prussia, and Austria; but Canning withdrew England from this intervention,–a great service to his country and to civilization. In fact, the great principle of his political life was non-intervention in the internal affairs of other nations. Hence he refused to join the great Powers in re-seating the king of Spain on his throne, from which that monarch had been temporarily ejected by a popular insurrection. But for him, the great Powers might have united with Spain to recover her lost possessions in South America. To him the peace of the world at that critical period was mainly owing. In one of his most famous speeches he closed with the oft-quoted sentence, “I called the New World into existence to redress the balance of the Old.”

Canning, like Peel,–and like Gladstone in our own time,–grew more and more liberal as he advanced in years, in experience, and in power, although he never left the Tory ranks. His commercial policy was identical with that of his friend Huskisson, which was that commerce flourished best when wholly unfettered by restrictions. He held that protection, in the abstract, was unsound and unjust; and thus he opened the way for free-trade,–the great boon which Sir Robert Peel gave to the nation under the teachings of Cobden. He also was in favor of Catholic emancipation and the repeal of the Test Act, which the Duke of Wellington was compelled against his will ultimately to give to the nation.

At the head of all this array of brilliant statesmen stood the king, or in this case the regent, who was a man of very different character from most of the ministers who served him.

It was in January, 1811, that the Prince of Wales became regent in consequence of the insanity of his father, George III.; it was during the Peninsular War, when Wellington, then Sir Arthur Wellesley, was wearing out the French in Spain. But the reign of this prince as regent is barren of great political movements. There is scarcely anything to record but riots and discontent among the lower classes, and the incendiary speeches and writings of demagogues. Measures of relief were proposed in Parliament, also for parliamentary reform and the removal of Catholic disabilities; but they were all alike opposed by the Tory government, and came to nothing. Four years after the beginning of the regency saw the overthrow of Napoleon, and the nation was so wearied of war and all great political excitement that it had sunk to inglorious repose. It was the period of reaction, of ultra conservatism, and hatred of progressive and revolutionary ideas, when such men as Cobbett and Hunt (Henry) were persecuted, fined, and imprisoned for their ideas. Cobbett, the most popular writer of the day, was forced to fly to America. Government was utterly intolerant of all political agitation, which was chiefly confined to men without social position.

But of all the magnates who were opposed to reform, the prince regent was the most obstinate. He was wholly devoted to pleasure. His court at the Carleton palace was famous for the assemblage of wits and beauties and dandies, reminding us of the epicureanism which marked Versailles during the reign of Louis XV. It was the most scandalous period in England since the times of Charles II. The life of the regent was a perpetual scandal, especially in his heartless treatment of women, and the disgraceful revels in which he indulged.

The companions of the prince were mostly dissipated and ennuied courtiers, as impersonated in that incarnation of dandyism who went by the name of Beau Brummell,–a contemptible character, who yet, it seems, was the leader of fashion, especially in dress, of which the prince himself was inordinately fond. This boon companion of royalty required two different artists to make his gloves, and he went home after the opera to change his cravat for succeeding parties. His impertinence and audacity exceeded anything ever recorded of men of fashion,–as when he requested his royal master to ring the bell. Nothing is more pitiable than his miserable end, deserted by all his friends, a helpless idiot in a lunatic asylum, having exhausted all his means. Lord Yarmouth, afterward the Marquis of Hertford, infamous for his debaucheries and extravagance, was another of the prince’s companions in folly and drunkenness. So was Lord Fife, who expended £80,000 on a dancer; and a host of others, who had, however, that kind of wit which would “set the table on a roar,”–but all gamblers, drunkards, and sensualists, who gloried in the ruin of those women whom they had made victims of their pleasures.

But I pass by the revelries and follies of “the first gentleman” in the realm, as he was called, to allude to one event which has historical importance, and which occupied the attention of the whole country,–and that was the persecution of his wife, who was also his cousin, Caroline Amelia Elizabeth, daughter of the Duke of Brunswick. He drove her from the nuptial bed, and from his palace. He sought also to get a divorce, which failed by reason of the transcendent talents and eloquence of Brougham and Denman, eminent lawyers whom she employed in her defence, and which brought them out prominently before the eyes of the nation,–for the great career of Brougham, especially, began with the trial of Caroline of Brunswick, the unhappy woman whom the Prince of Wales married to get relief from his pecuniary necessities, and whom he insulted as soon as he saw her, although she was a princess of considerable accomplishments, and as amiable as she was beneficent. The only palliation of his infamous treatment of this woman was that he never loved her, and was even disgusted with her. No sooner was the marriage solemnized, than she was treated on every occasion with studied contumely, and scarcely had she recovered from illness incident to the birth of the Princess Charlotte, when the “first gentleman of the age” was pleased to intimate that it suited his disposition that they should hereafter live apart. Never allowed to be crowned as queen, driven from the shelter of her husband’s roof, surrounded with spies, accused of crimes of which there was no proof, even excluded from the public prayers, and finally forced into exile, she sank under her accumulated wrongs, and was carried off by a fatal illness at the age of fifty-three.

On the death of the old king in 1820, the Prince of Wales became George IV., after having been regent for nine years. As he was inflexibly opposed to all reforms, no great measures had been carried through Parliament except from urgent necessity and fear of revolution. But the State was being prepared for reforms in the next reign. In 1820 the agitation, which finally ended in the Reform Bill, set in with great earnestness. Henry Brougham had become a great power in the House of Commons, and poured out the vials of his wrath on the Tory government. Lord John Russell busily employed himself in forging the weapons by which he, more than any other man, afterward broke the power of the Tories. The voice of Wilberforce was also heard in demanding the abolition of negro slavery. Romilly was advocating a reform in criminal law. Macaulay was making those brilliant speeches which would have elevated him to the highest rank among debaters had he not cherished other ambitions.

The only things which stand out as memorable and of political importance in this reign were a change in the foreign policy of England, the discontents and agitations of the people, the removal of Catholic disabilities, and the repeal of the Test Acts.

On the first I shall not dwell, since I have already alluded to it as the great work of Canning. As foreign minister he divorced England from the Holy Alliance, and insisted on maintaining non-intervention in the internal affairs of other nations, and a peace policy which raised his country to the highest pinnacle of power she ever attained, and brought about a development of wealth and industry entirely unprecedented. Had he lived he would have carried out those reforms that later were the glory of Lord John Russell and Sir Robert Peel, for he was emancipated from the ideas which made the Tories obnoxious. His spirit was liberal and progressive, and hence he incurred bitter hostilities. The government, however, could not be carried on without him, and the king was forced unwillingly to accept him as minister. His magnificent services as foreign secretary had mollified the hostilities of George IV., who became anxious to retain him in power at the head of the foreign department, after the retirement of Lord Liverpool. But Canning felt that the premiership was his due, and would accept nothing short of it, and the king was forced to give it to him in spite of the howl of the Tory leaders. He enjoyed that dignity, however, but two months, being worn out with labors, and embittered by the hostilities of his political enemies, who hounded him to death with the most cruel and unrelenting hatred. His sensitive and proud nature could not stand before such unjust attacks and savage calumnies. He rapidly sank, in the prime of his life and in the height of his fame. Canning’s death in 1827 was a marked event in the reign of George IV.; it filled England with mourning, and never was grief for a departed statesman more sincere and profound. He was buried with great pomp in Westminster Abbey. The sculptor Chantry was intrusted with the execution of his statue,–a memorial which he did not need, for his fame is imperishable. The day after the funeral his wife was made a peeress, an annuity was granted to his sons, and every honor that it was possible for a grateful nation to bestow was lavished on his memory.

Canning left only £20,000,–a less sum than he had received from his wife upon his marriage. His domestic life was singularly happy. He was also happy in the brilliant promises of his sons, one of whom became governor-general of India, and was created a peer for his services. His only daughter married the Marquis of Clanricarde. His children thus entered the ranks of the nobility,–a distinction which he himself did not covet. It was his chief ambition to rule the nation through the House of Commons.

Some authorities have regarded Canning as the greatest of English parliamentary orators; but his speeches to me are disappointing, although elaborate, argumentative, logical, and full of fancy and wit. They were too rhetorical to suit the taste of Lord Brougham. Rhetorical exhibitions, however brilliant, are not those which posterity most highly value, and lose their charm when the occasions which produced them have passed away. Canning’s presence was commanding and dignified, his articulation delicate and precise, his voice clear and musical; while the curl of his lip and the glance of his eye would silence almost any antagonist. In cabinet meetings he was habitually silent, having already made up his mind. He could not gracefully bear contradiction, and made many enemies by his pride and sarcasm. In private life he was courteous and gentlemanly, fond of society, but fonder of domestic life, pure in his moral character, devoted to his family,–especially to his mother, whom he treated with extraordinary deference and affection.

The next subject of historical importance in the reign of George IV. was the perpetual agitation among the people growing out of their misery and discontent. There were no great insurrections to overturn the throne, as in Spain and Italy and France; but there was a fierce demand for the removal of evils which were intolerable; and this was manifested in monster petitions to Parliament, in incendiary speeches like those made by “Orator Hunt” and other agitators, in such political tracts as Cobbett wrote and circulated in every corner of the land, in occasional uprisings among agricultural laborers and factory operatives, in angry mobs destroying private property,–all impelled by hunger and despair. To these discontents and angry uprisings the government was haughty and cold, looking upon them as revolutionary and dangerous, and putting them down by sheriffs and soldiers, by coercion bills and the suspension of the Act of habeas corpus. Some speeches were made in Parliament in favor of education, and some efforts in behalf of law reforms,–especially the removal of the death penalty for small offences, more than two hundred of which were punishable with death. Numerous were the instances where men and boys were condemned to the gallows for stealing a coat or shooting a hare; but the sentences of judges were often not enforced when unusually severe or unjust. Moreover, large charities were voted for the poor, but without materially relieving the general distress.

On the whole, however, the country increased in wealth and prosperity in consequence of the long and uninterrupted peace; and the only great drawback was the mercantile crisis of 1825, resulting from the mania of speculation, and followed by the contraction of the currency,–the effect of which was the failure of banks and the ruin of thousands who had calculated on being suddenly enriched. Alison estimates the shrinkage of property in Great Britain alone as at least £100,000,000. Men worth £100,000 could not at one time raise £100. The banks were utterly drained of gold and silver. Nothing prevented universal bankruptcy but the issue of small bills by the Bank of England. There was a lull of political excitement after the trial of Queen Caroline, and Parliament confined itself chiefly to legal, economical, and commercial questions; although occasionally there were grand debates on the foreign policy, on Catholic emancipation, and on the disfranchisement of corrupt boroughs. Ireland obtained considerable parliamentary attention, owing to the failure of the potato crop and its attendant agricultural distress, which produced a state bordering on rebellion, and to the formation of the Catholic Association.

But the great event in the political history of England during the reign of George IV. was unquestionably the removal of Catholic disabilities,–ranking next in importance and interest with the Reform Bill and the repeal of the Corn Laws. Catholic disability had existed ever since the reign of Elizabeth, and was the standing injustice under which Ireland labored. Catholic peers were not admitted to the House of Lords, nor Catholics to a seat in the House of Commons,–which was a condition of extremely unequal representation. In reality, only the Protestants were represented in Parliament, and they composed only about one tenth of the whole population.

In addition to this injustice, the Irish, who were mostly Roman Catholics, were ground down by such oppressive laws that they were really serfs to those landlords who owned the soil on which they toiled for a mere pittance,–about fourpence a day,–resulting in a general poverty such as has never before been seen in any European country, with its attendant misery and crime. The miserable Irish peasantry lived in mud huts or cabins, covered partially with thatch, but not enough to keep out the rain. No furniture and no comforts were to be seen in these huts. There were no chairs or tables, only a sort of dresser for laying a plate upon; no cooking utensils but a cast-metal pot to boil potatoes,–almost the only food. There were no bedsteads, and but few blankets. The people slept in their clothes, the whole family generally in one room,–the only room in the cabin. For fuel they burned peat. In order to pay their rent, they sold their pigs. Beggars infested every road and filled every village. No one was certain of employment, even at twopence a day. Everybody was controlled by the priests, whose power rested on their ability to stimulate religious fears, and who were supported by such contributions as they were able to extort from the superstitious and ignorant people,–by nature brave and generous and joyous, but improvident and reckless. It was the wonder of O’Connell how they could remain cheerful amid such privations and such wrongs, with the government seemingly indifferent, with none to pity and few to help. Nor could they vote for the candidates for any office whatever unless they had freeholds, or life-rent possessions, for which they paid a rent of forty shillings. The landlords of this wretched tenantry, unable to face the misery they saw and which they could not relieve, or fearful of assassination, left the country to spend their incomes in the great cities of Europe, not being united with their people by any ties, social or religious.

What wonder that such a wretched people, urged by the priests, should form associations for their own relief, especially when famine pressed and landlords exacted the uttermost farthing,–when the crimes to which they were impelled by starvation were punished with the most inexorable severity by Protestant magistrates in whose appointment they had no hand!

The result was the rise of the Catholic Association, the declared object of which was to forward petitions to Parliament, to support an independent Press, to aid emigration to America,–all worthy, and unobjectionable on the surface, but with the real intent (as affirmed by the Tories and believed by a large majority of the nation) of securing the control of elections, of bringing about the repeal of the Union with England (which, enacted in 1801, had done away with the separate Irish parliament), the resumption of the Church property by the Catholic clergy, and the restoration of the Catholic faith as the dominant religion of the land. Such an Association, embracing most of the Roman Catholic population, was regarded with great alarm by the government; and they determined to put it down as seditious and dangerous, against the expostulation of such men as Brougham, Mackintosh, and Sir Henry Parnell. Then arose the great figure of O’Connell in the history of Ireland (whose eloquence, tact, and ability have no parallel in that country of orators), defending the cause of his countrymen with masterly power, leading them like a second Moses according to his will,–in fact, uniting them in a movement which it was hopeless to oppose except with an army bent on the depopulation of the country; so that George IV. is reported to have said, with considerable bitterness, “Canning is king of England, O’Connell is king of Ireland, and I am Dean of Windsor.”

Such, however, was the hostility of Parliament to the Irish Catholics that a bill was carried by a great majority in both Houses to suppress the Association, supported powerfully by the Duke of York as well as by the ministers of the crown, even by Canning himself and Sir Robert Peel.

Then followed renewed disturbances, riots, and murders; for the condition of the Roman Catholics in Ireland was desperate as well as gloomy. The Association was dissolved, for O’Connell would do nothing unlawful; but a new one took its place, which preached peace and unity, but which meant the repeal of the Union,–the grand object that from first to last O’Connell had at heart. Of course, this scheme was utterly impracticable without a revolution that would shake England to its centre; but it was followed by an immense emigration to America,–so great that the population of Ireland declined from eight and a half to four and a half millions. The Irish Catholics, however, were comparatively quiet during the administration of Mr. Canning, whose liberal tendencies had given them hope; but on his death they became more restive. The coalition ministry under Lord Goderich was much embarrassed how to act, or was too feeble to act with vigor,–not for want of individual abilities, but by reason of dissensions among the ministers. It lasted only a short time, and was succeeded by that of the Duke of Wellington, with Sir Robert Peel for his lieutenant; both of whom had shown an intense prejudice and dislike of the Irish Catholics, and had voted uniformly for their repression. On the return of the Tories to power, the Irish disturbances were renewed and increased. Hitherto the landlords had directed the votes of their tenantry,–the forty-shilling freeholders; but now the elections were determined by the direction of the Catholic Association, which was controlled by the priests, and by O’Connell and his associates. In addition, O’Connell himself was elected to represent in the English Parliament the County of Clare, against the whole weight of the government,–which was a bitter pill for the Tories to swallow, especially as the great agitator declared his intention to take his seat without submitting to the customary oath. It was in reality a defiance of the government, backed by the whole Irish nation. The Catholics became so threatening, they came together so often and in such enormous masses, that the nation was thoroughly alarmed. The king and a majority of his ministers urged the most violent coercive measures, even to the suspension of habeas corpus.

O’Connell was not admitted to Parliament; but his case precipitated an intense turmoil, which settled the question forever; for then the great general who had defeated Napoleon, and was the idol of the nation, seeing the difficulties of coercion as no other statesman did, and influenced by Sir Robert Peel (for whom he had unbounded respect), made one of his masterly retreats, by which he averted revolution and bloodshed. Wellington hated the Catholics, and was a most loyal member of the Church of England; moreover, he was a Tory and an ultra-conservative. But at last even his eyes were opened, not to the injustices and wrongs which ground Ireland to the dust, but to the necessity of conciliation. Like Peel, he could face facts; and when his path was clear he would walk therein, whatever kings or ministers or peers or people might think or say. He resolved to emancipate the Catholics, as Sir Robert Peel afterward repealed the Corn Laws, against all his antecedents and affiliations and sympathies, and more than all against the declared wishes and resolutions of the monarch whom he nominally served, yet whom he controlled by his iron will. Sir Robert Peel, as obstinate a Tory as his chief, had been for some time convinced of the necessity of conciliation, and at once resigned his seat as the representative of Oxford University, which he felt he could no longer honorably hold. In March, 1829, he brought forward his bill for the removal of Catholic disabilities, which was read the third time, and passed the Commons by a majority of 178. In the House of Peers, it was carried by a majority of 104,–so great was the influence of Wellington and Peel, so impressed at last were both Houses of the necessity for the measure.

The difficulty now was to obtain the signature of the king, although he had promised it as the probable alternative of revolution,–a great State necessity, which his ministers had made him at last perceive, but to which he reluctantly yielded. He was somewhat in the position of Pope Clement XIV. when obliged, against his will and against the interests of the Catholic Church, to sign the bull for the revocation of the charter of the Jesuits. Compulsus feci! compulsus feci! he exclaimed, with mental agony. George IV. could have said the same. He procrastinated; he lay all day in bed to avoid seeing his ministers; he talked of his feelings; he threatened to abdicate, and go to Hanover; he would not violate his conscience; he would be faithful to the traditions of his house and the memory of his father,–and so on, until the patience of Wellington and Peel was exhausted, and they told him he must sign the bill at once, or they would immediately resign. “The king could no longer wriggle off the hook,” and surrendered. O’Connell was instantly re-elected, and took his seat in Parliament,–a position which he occupied for the rest of his life. George IV. was the last of the monarchs of England who attempted to rule by personal government. Henceforward the monarch’s duty was simply to register the decrees of Parliament.

But the admission of Catholics to Parliament did not heal the disorders of Ireland as had been hoped. The Irish clamored for still greater privileges. The cry for repeal of the Union succeeded that for the removal of disabilities. Their poverty and miseries remained, while their monster meetings continued to shake the kingdom to its centre.

The historical importance of Catholic emancipation consists in this,–that it was the first great victory over the aristocratic powers of the empire, and was an entrance wedge to the reform of Parliament effected in the next reign. It threw forty or fifty members of the House of Commons into the ranks of opposition to the Tory side, which with a few brief intervals had governed England for a century. “The reform movement was the child of Catholic agitation; the anti-corn law league that of the triumph of reform.” Brougham was the legitimate successor of O’Connell. A foresight of such consequences was the real cause of the movement being so bitterly opposed by the king and Lord Eldon. It was not jealousy of the Catholics that moved them,–that was only the pretence; it was really fear of the blow aimed against Toryism. They had sagacity enough to see the inevitable result,–the advancing power of the Liberal party, and the impossibility of longer ruling the country without ceding privileges to the people. The repeal of the Test Act by the previous administration, which removed the disabilities of Dissenters from the Established Church to hold public office, was only another act in the great drama of national development which was to give ascendency to the middle class in matters of legislation, rather than to the favored classes who had hitherto ruled. The movement was political and not religious, whatever might be the hatred of the Tories for both Catholics and Dissenters.

Nothing further of political importance marked the administration of the Duke of Wellington except the increasing agitations for parliamentary reform, which will be hereafter considered. Wellington was elevated to his exalted post from the influence and popularity which followed his military achievements. His fame, like that of General Grant, rests on his military and not on his civil services, although his great experience as a diplomatist and general made him far from contemptible as a statesman. It was his misfortune to hold the helm of state in stormy times, amid riots, agitations, insurrections, and party dissensions, amid famines and public distresses of every kind; when England was going through a transition state, when there was every shade of opinion among political leaders. The duke, like Canning before him, was isolated, and felt the need of a friend. He was not like a commander-in-chief surrounded with a band of devoted generals, but with ministers held together by a rope of sand. He had no real colleagues in his cabinet, and no party in the House of Commons. The chief troubles in England were financial rather than political, and he had no head for finance like Huskisson and Sir Robert Peel.

In the midst of the difficulties with which the great duke had to contend, George IV. died, June 26, 1830. He was in his latter days a great sufferer from the gout and other diseases brought about by the debaucheries of his earlier days; and he was a disenchanted man, living long enough to see how frail were the supports on which he had leaned,–friends, pleasures, and exalted rank.

All authorities are agreed as to the character of George IV., though some in their immeasurable contempt have painted him worse than he really was, like Brougham and Thackeray. All are agreed that he was selfish and pleasure-seeking in his ordinary life, though courteous in his manners and kind to those who shared his revels. As dissipated habits obtained the mastery over him, and the unbounded flattery of his boon companions stultified his conscience, he became heartless and even brutal. He was proud and overbearing; was fond of pomp and ceremony, and ultra-conservative in all his political views. He was outrageously extravagant and reckless in his expenditures, and then appealed to Parliament to pay his debts. He liked to visit his favorites, and received visits from them in return so long as his physical forces remained; but when these were hopelessly undermined by self-indulgence, he buried himself in his palaces, and rarely appeared in public. Indeed, in his latter days he shunned the sight of the people altogether. His character appears better in his letters than in the verdicts of historians. Those written to his Chancellor Eldon, to the Duke of Wellington, to Lord Liverpool, to Sir William Knighton, keeper of the privy purse, and others, show great cordiality, frankness, and the utter absence of the stiffness and pride incident to his high rank. They abound in expressions of kindness and even affection, whether sincere or not. They are all well written, and would do credit, from a literary point of view, to any private person. His talents and conversation, his wit and repartee, and his felicitous description of character are undeniable. He is said to have had the talent of telling stories to perfection. His powers of mimicry were remarkable, and he was fond of singing songs at his banquets. Had he been simply a private person or an ordinary nobleman, he would have been far from contemptible.

The latter days of George IV. were sad, and for a king he was left comparatively alone. He had neither wife nor children to lean upon and to cheer him,–only mercenary courtiers and physicians. His tastes were refined, his manners affable, and his conversation interesting. He was intelligent, sagacious, and well-informed; yet no English monarch was ever more cordially despised. The governing principle of his life was a love of ease and pleasure, which made him negligent of his duties; and there never yet lived a man, however exalted his sphere, who had not imperative duties to perform, without the performance of which his life was a failure and a reproach. So it was with this unhappy king, who died like Louis XV. without any one to mourn his departure; and a new king reigned in his stead.

And yet the reign of the fourth George as king was marked by returning national prosperity,–owing not to the efforts of statesmen and legislators, but to the marvellous spread of commerce and manufactures, resulting from the establishment of peace, thus opening a market for British goods in all parts of the world.

This period of the fourth George’s rule, as regent and king, was also remarkable for the appearance of men of genius in all departments of human thought and action. As the lights of a former generation sank beneath the horizon, other stars arose of increased brilliancy. In poetry alone, Byron, Scott, Rogers, Coleridge, Southey, Wordsworth, Moore, Campbell, Keats, would have made the age illustrious,–a constellation such as has not since appeared. In fiction, Sir Walter Scott introduced a new era, soon followed by Bulwer, Dickens, and Thackeray. In the law there were Brougham, Eldon, Lyndhurst, Ellenborough, Denman, Plunkett, Erskine, Wetherell,–all men of the first class. In medicine and surgery were Abernethy, Cooper, Holland. In the Church were Parr, Clarke, Hampden, Scott, Sumner, Hall, Arnold, Irving, Chalmers, Heber, Whately, Newman. Sir Humphry Davy was presiding at the Royal Society, and Sir Thomas Lawrence at the Royal Academy. Herschel was discovering planets. Bell was lecturing at the new London University, and Dugald Stewart in the University of Edinburgh. Captain Ross was exploring the Northern Seas, and Lander the wilds of Africa. Lancaster was founding a new system of education; Bentham and Ricardo were unravelling the tangled web of political economy; Hallam, Lingard, Mitford, Mills, were writing history; Macaulay, Carlyle, Smith, Lockhart, Jeffrey, Hazlitt, were giving a new stimulus to periodical literature; while Miss Edgeworth, Jane Porter, Mrs. Hemans, were entering the field of literature as critics, poets, and novelists, instead of putting their inspired thoughts into letters, as bright women did one hundred years before. Into everything there were found some to cast their searching glances, creating an intellectual activity without previous precedent, if we except the great theological discussions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Even shopkeepers began to read and think, and in their dingy quarters were stirred to discuss their rights; while William Cobbett aroused a still lower class to political activity by his matchless style. All philanthropic, educational, and religious movements received a wonderful stimulus; while improvements in the use of steam, mechanical inventions, chemical developments and scientific discoveries, were rapidly changing the whole material condition of mankind.

In 1820, when the regent became George IV., a new era opened in English history, most observable in those popular agitations which ushered in reforms under his successor William IV. These it will be my object to present in another volume.

Authorities.

Croly’s Life of George IV.; Thackeray’s Four Georges; Annual Register; Life of the Duke of Wellington; Life of Canning; Life of Lord Liverpool; Life of Lord Brougham; Miss Martineau’s History of England; Life of Mackintosh; Life of Sir Robert Peel; Alison’s History of Europe; Life of Lord Eldon; Life of O’Connell; Molesworth’s History of England.