Prince Metternich : Conservatism – Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

Mirabeau : The French Revolution

Edmund Burke : Political Morality

Napoleon Bonaparte : The French Empire

Prince Metternich : Conservatism

Chateaubriand : The Restoration and Fall of the Bourbons

George IV : Toryism

The Greek Revolution

Louis Philippe : The Citizen King

Beacon Lights of History, Volume IX : European Statesmen

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Europe in the Napoleonic Era

Birth and family of Metternich

University Life

Metternich in England

Marriage of Metternich

Ambassador at Dresden

Ambassador at Berlin

Austrian aristocracy

Metternich at Paris

Metternich on Napoleon

Metternich, Chancellor and Prime Minister

Designs of Napoleon

Napoleon marries Marie Louise

Hostility of Metternich

Frederick William III

Coalition of Great Powers

Congress of Vienna

Subdivision of Napoleon conquests

Holy Alliance

Burdens of Metternich

His political aims

His hatred of liberty

Assassination of von Kotzebue

Insurrection of Naples

Insurrection of Piedmont

Spanish Revolution

Death of Emperor Francis

Tyranny of Metternich

His character

His services

Prince Metternich : Conservatism

1773-1859.

In the later years of Napoleon’s rule, when he had reached the summit of power, and the various German States lay prostrate at his feet, there arose in Austria a great man, on whom the eyes of Europe were speedily fixed, and who gradually became the central figure of Continental politics. This remarkable man was Count Metternich, who more than any other man set in motion the secret springs which resulted in a general confederation to shake off the degrading fetters imposed by the French conqueror. In this matter he had a powerful ally in Baron von Stein, who reorganized Prussia, and prepared her for successful resistance, when the time came, against the common enemy. In another lecture I shall attempt to show the part taken by Von Stein in the regeneration of Germany; but it is my present purpose to confine attention to the Austrian chancellor and diplomatist, his various labors, and the services he rendered, not to the cause of Freedom and Progress, but to that of Absolutism, of which he was in his day the most noted champion.

Metternich, in his character as diplomatist, is to be contemplated in two aspects: first, as aiming to enlist the great powers in armed combination against Napoleon; and secondly, as attempting to unite them and all the German States to suppress revolutionary ideas and popular insurrections, and even constitutional government itself. Before presenting him in this double light, however, I will briefly sketch the events of his life until he stood out as the leading figure in European politics,–as great a figure as Bismarck later became.

Clemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Count von Metternich, was born at Coblentz, on the Rhine, May 15, 1773. His father was a nobleman of ancient family. I will not go into his pedigree, reaching far back in the Middle Ages,–a matter so important in the eyes of German and even English biographers, but to us in America of no more account than the genealogy of the Dukes of Edom. The count his father was probably of more ability than an ordinary nobleman in a country where nobles are so numerous, since he was then, or soon after, Austrian ambassador to the Netherlands. Young Metternich was first sent to the University of Strasburg, at the age of fifteen, about the time when Napoleon was completing his studies at a military academy. In 1790, a youth of seventeen, he took part in the ceremonies attending the coronation of Emperor Leopold at Frankfort, and made the acquaintance of the archduke, who two years later succeeded to the imperial dignity as Francis II. We next see him a student of law in the University of Mainz, spending his vacations at Brussels, in his father’s house.

Even at that time Metternich attracted attention for his elegant manners and lively wit,–a born courtier, a favorite in high society, and so prominent for his intelligence and accomplishments that he was sent to London as an attaché to the Netherlands embassy, where it seems that he became acquainted with the leading statesmen of England. There must have been something remarkable about him to draw, at the age of twenty, the attention of such men as Burke, Pitt, Fox, and Sheridan. What interested him most in England were the sittings of the English Parliament and the trial of Warren Hastings. At the early age of twenty-one he was appointed minister to the Hague, but was prevented going to his post by the war, and retired to Vienna, which he now saw for the first time. Soon after, he married a daughter of Prince Kaunitz, eldest son of the great chancellor who under three reigns had controlled the foreign policy of the empire. He thus entered the circle of the highest nobility of Austria,–the proudest and most exclusive on the face of the whole earth.

At first the young count–living with his bride at the house of her father, and occupying the highest social position, with wealth and ease and every luxury at command, fond equally of books, of music, and of art, but still fonder of the distinguished society of Vienna, and above all, enamored of the charms of his beautiful and brilliant wife–wished to spend his life in elegant leisure. But his remarkable talents and accomplishments were already too well known for the emperor to allow him to remain in his splendid retirement, especially when the empire was beset with dangers of the most critical kind. His services were required by the State, and he was sent as ambassador to Dresden, after the peace of Luneville, 1801, when his diplomatic career in reality began.

Dresden, where were congregated at this time some of the ablest diplomatists of Europe, was not only an important post of observation for watching the movements of Napoleon, but it was itself a capital of great attractions, both for its works of art and for its society. Here Count Metternich resided for two years, learning much of politics, of art, and letters,–the most accomplished gentleman among all the distinguished people that he met; not as yet a man of power, but a man of influence, sending home to Count Stadion, minister of foreign affairs, reports and letters of great ability, displaying a sagacity and tact marvellous for a man of twenty-eight.

Napoleon was then engaged in making great preparations for a war with Austria, and it was important for Austria to secure the alliance of Prussia, her great rival, with whom she had never been on truly friendly terms, since both aimed at ascendency in Germany. Frederick William III. was then on the throne of Prussia, having two great men among his ministers,–Von Stein and Hardenberg; the former at the head of financial affairs, and the latter at the head of the foreign bureau. To the more important post of Berlin, Metternich was therefore sent. He found great difficulty in managing the Prussian king, whose jealousy of Austria balanced his hatred of Napoleon, and who therefore stood aloof and inactive, indisposed for war, in strict alliance with Russia, who also wanted peace.

The Czar Alexander I., who had just succeeded his murdered father Paul, was a great admirer of Napoleon. His empire was too remote to fear French encroachments or French ideas. Indeed, he started with many liberal sentiments. By nature he was kind and affectionate; he was simple in his tastes, truthful in his character, philanthropic in his views, enthusiastic in his friendships, and refined in his intercourse,–a broad and generous sovereign. And yet there was something wanting in Alexander which prevented him from being great. He was vacillating in his policy, and his judgment was easily warped by fanciful ideas. “His life was worn out between devotion to certain systems and disappointment as to their results. He was fitful, uncertain, and unpractical. Hence he made continual mistakes. He meant well, but did evil, and the discovery of his errors broke his heart. He died of weariness of life, deceived in all his calculations,” in 1825.

Metternich spent four years in Berlin, ferreting out the schemes of Napoleon, and striving to make alliances against him; but he found his only sincere and efficient ally to be England, then governed by Pitt. The king of Prussia was timid, and leaned on Russia; he feared to offend his powerful neighbor on the north and east. Nor was Prussia then prepared for war. As for the South German States, they all had their various interests to defend, and had not yet grasped the idea of German unity. There was not a great statesman or a great general among them all. They had their petty dynastic prejudices and jealousies, and were absorbed in the routine of court etiquette and pleasures, stagnant and unenlightened. The only brilliant court life was at Weimar, where Goethe reigned in the circle of his idolaters. The great men of Germany at that time were in the universities, interested in politics, like the Humboldts at Berlin, but not taking a prominent part. Generals and diplomatists absorbed the active political field. As for orators, there were none; for there were no popular assemblies,–no scope for their abilities. The able men were in the service of their sovereigns as diplomatists in the various courts of Europe, and generally were nobles. Diplomacy, in fact, was the only field in which great talents were developed and rewarded outside the realm of literature.

In this field Metternich soon became pre-eminently distinguished. He was at once the prompting genius and the agent of an absolute sovereign who ruled over the most powerful State, next to France, on the continent of Europe, and the most august. The emperor of Austria was supposed to be the heir of the Caesars and of Charlemagne. His territories were more extensive than that of France, and his subjects more numerous than those of all the other German States combined, except Prussia. But the emperor himself was a feeble man, sickly in body, weak in mind, and governed by his ministers, the chief of whom was Count Stadion, minister of foreign affairs. In Austria the aristocracy was more powerful and wealthy than the nobility of any other European State. It was also the most exclusive. No one could rise by any talents into their favored circle. They were great feudal landlords; and their ranks were not recruited, as in England, by men of genius and wealth. Hence, they were narrow, bigoted, and arrogant; but they had polished and gracious manners, and shone in the stiff though elegant society of Vienna,–not brilliant as in Paris or London, but exceedingly attractive, and devoted to pleasure, to grand hunting-parties on princely estates, to operas and balls and theatres. Probably Vienna society was dull, if it was elegant, from the etiquette and ceremonies which marked German courts; for what was called society was not that of distinguished men in letters and art, but almost exclusively that of nobles. A learned professor or wealthy merchant could no more get access to it than he could climb to the moon. But as Vienna was a Catholic city, great ecclesiastical dignitaries, not always of noble birth, were on an equality with counts and barons. It was only in the Church that a man of plebeian origin could rise. Indeed, there was no field for genius at all. The musician Haydn was almost the only genius that Austria at that time possessed outside of diplomatic or military ranks.

Napoleon had now been crowned emperor, and his course had been from conquering to conquer. The great battles of Austerlitz and Jena had been fought, which placed Austria and Prussia at the mercy of the conqueror. It was necessary that some one should be sent to Paris capable of fathoming the schemes of the French emperor, and in 1806 Count Metternich was transferred from Berlin to the French capital. No abler diplomatist could be found in Europe. He was now thirty-three years of age, a nobleman of the highest rank, his father being a prince of the empire. He had a large private fortune, besides his salary as ambassador. His manners were perfect, and his accomplishments were great. He could speak French as well as his native tongue. His head was clear; his knowledge was accurate and varied. Calm, cold, astute, adroit, with infinite tact, he was now brought face to face with Talleyrand, Napoleon’s minister of foreign affairs, his equal in astuteness and dissimulation, as well as in the charms of conversation and the graces of polished life. With this statesman Metternich had the pleasantest relations, both social and diplomatic. Yet there was a marked difference between them. Talleyrand had accepted the ideas of the Revolution, but had no sympathy with its passions and excesses. He was the friend of law and order, and in his heart favored constitutional government. On this ground he supported Napoleon as the defender of civilization, but afterward deserted him when he perceived that the Emperor was resolved to rule without constitutional checks. His nature was selfish, and he made no scruple of enriching himself, whatever master he served; but he was not indifferent to the welfare and glory of France. Metternich, on the other hand, abhorred the ideas of the Revolution as much as he did its passions. He saw in absolutism the only hope of stability, the only reign of law. He distrusted constitutional government as liable to changes, and as unduly affected by popular ideas and passions. He served faithfully and devotedly his emperor as a sacred personage, ruling by divine right, to whom were intrusted the interests of the nation. He was comparatively unselfish, and was prepared for any personal sacrifices for his country and his sovereign.

Metternich was treated with distinguished consideration at Paris, not only because he was the representative of the oldest and proudest sovereignty in Europe,–still powerful in the midst of disasters,–but also on account of his acknowledged abilities, independent attitude, and stainless private character. All the other ambassadors at Paris were directed to act in accordance with his advice. In 1807 he concluded the treaty of Fontainebleau, which was most favorable to Austrian interests. He was the only man at court whom Napoleon could not browbeat or intimidate in his affected bursts of anger. Personally, Napoleon liked him as an accomplished and agreeable gentleman; as a diplomatist and statesman the Emperor was afraid of him, knowing that the Austrian was at the bottom of all the intrigues and cabals against him. Yet he dared not give Metternich his passports, nor did he wish to quarrel with so powerful a man, who might defeat his schemes to marry the daughter of the Austrian emperor,–the light-headed and frivolous Marie Louise. So Metternich remained in honor at Paris for three years, studying the character and aims of Napoleon, watching his military preparations, and preparing his own imperial master for contingencies which would probably arise; for Napoleon was then meditating the conquest of Spain, as well as the invasion of Russia, and Metternich as well as Talleyrand knew that this would be a great political blunder, diverting his armies from the preservation of the conquests he had already made, and giving to the German States the hope of shaking off their fetters at the first misfortune which should overtake him. No man in Europe so completely fathomed the designs of Napoleon as Metternich, or so profoundly measured and accurately estimated his character. And I here cannot forbear to quote his own language, both to show his sagacity and to reproduce the portrait he drew of Napoleon.

“He became,” says Metternich, “a great legislator and administrator, as he became a great soldier, by following out his instincts. The turn of his mind always led him toward the positive. He disliked vague ideas, and hated equally the dreams of visionaries and the abstractions of idealists. He treated as nonsense everything that was not clearly and practically presented to him. He valued only those sciences which can be verified by the senses, or which rest on experience and observation. He had the greatest contempt for the false philosophy and false philanthropy of the eighteenth century. Among its teachers, Voltaire was the special object of his aversion. As a Catholic, he recognized in religion alone the right to govern human societies. Personally indifferent to religious practices, he respected them too much to permit the slightest ridicule of those who followed them; and yet religion with him was the result of an enlightened policy rather than an affair of sentiment. He was persuaded that no man called to public life could be guided by any other motive than that of interest.

“He was gifted with a particular tact in recognizing those men who could be useful to him. He had a profound knowledge of the national character of the French. In history he guessed more than he knew. As he always made use of the same quotations, he must have drawn from a few books, especially abridgments. His heroes were Alexander, Caesar, and Charlemagne. He laid great stress on aristocratic birth and the antiquity of his own family. He had no other regard for men than a foreman in a manufactory feels for his work-people. In private, without being amiable, he was good-natured. His sisters got from him all they wanted. Simple and easy in private life, he showed himself to little advantage in the great world. Nothing could be more awkward than he in a drawing-room. He would have made great sacrifices to have added three inches to his height. He walked on tiptoe. His costumes were studied to form a contrast with the circle which surrounded him, by extreme simplicity or extreme elegance. Talma taught him attitudes.

“Having but one passion,–that of power,–he never lost either his time or his means in those objects which deviated from his aims. Master of himself, he soon became master of events. In whatever period he had appeared, he would have played a prominent part. His prodigious successes blinded him; but up to 1812 he never lost sight of the profound calculations by which he so often conquered. He never recoiled from fear of the wounds he might cause. As a war-chariot crushes everything it meets on its way, he thought of nothing but to advance. He could sympathize with family troubles; he was indifferent to political calamities.

“Disinterested generosity he had none; he only dispensed his favors in proportion to the value he put on the utility of those who received them. He was never influenced by affection or hatred in his public acts. He crushed his enemies without thinking of anything but the necessity of getting rid of them.

“In his political combinations he did not fail to reckon largely on the weakness or errors of his adversaries. The alliance of 1813 crushed him because he was not able to persuade himself that the members of the coalition could remain united, and persevere in a given course of action. The vast edifice he constructed was exclusively the work of his own hands, and he was the keystone of the arch; but the gigantic construction was essentially wanting in its foundations, the materials of which were nothing but the ruins of other buildings.”

Such is the verdict of one of the acutest and most dispassionate men that ever lived. Napoleon is not painted as a monster, but as a supremely selfish man bent entirely on his own exaltation, making the welfare of France subservient to his own glory, and the interests of humanity itself secondary to his pride and fame. History can add but little to this graphic sketch, although indignant and passionate enemies may dilate on the Corsican’s hard-heartedness, his duplicity, his treachery, his falsehood, his arrogance, and his diabolic egotism. On the other hand, weak and sentimental idolaters will dwell on his generosity, his courage, his superhuman intellect, and the love and devotion with which he inspired his soldiers,–all which in a sense is true. The philosophical historian will enumerate the services Napoleon rendered to his country, whatever were his virtues or faults; but of these services the last person to perceive the value was Metternich himself, even as he would be the last to acknowledge the greatness of those revolutionary ideas of which Napoleon was simply the product. It was the French Revolution which produced Napoleon, and it was the French Revolution which Metternich abhorred, in all its aspects, beyond any other event in the whole history of the world. But he was not a rhetorician, as Burke was, and hence confined himself to acts, and not to words. He was one of those cool men who could use decent and temperate language about the Devil himself and the Pandemonium in which he reigns.

On the breaking up of diplomatic relations between Austria and France in 1809, Metternich was recalled to Vienna to take the helm of state in the impending crisis. Count von Stadion, though an able man, was not great enough for the occasion. Only such a consummate statesman as Metternich was capable of taking the reins intrusted to him with unbounded confidence by his feeble master, whose general policy and views were similar to those of his trusted minister, but who had not the energy to carry them out. Metternich was now made a prince, with large gifts of land and money, and occupied a superb position,–similar to that which Bismarck occupied later on in Prussia, as chancellor of the empire. It was Metternich’s policy to avert actual hostilities until Austria could recover from the crushing defeat at Austerlitz, and until Napoleon should make some great mistake. He succeeded in arranging another treaty with France within the year.

The object which Napoleon had in view at this time was his marriage with Marie Louise, from which he expected an heir to his vast dominions, and a more completely recognized position among the great monarchs of Europe. He accordingly divorced Josephine,–some historians say with her consent. Ten years earlier his offers would, of course, have been indignantly rejected, or three years later, after the disasters of the Russian campaign. But Napoleon was now at the summit of his power,–the arbiter of Europe, the greatest sovereign since Julius Caesar, with a halo of unprecedented glory, a prodigy of genius as well as a recognized monarch. Nothing was apparently beyond his aspirations, and he wanted the daughter of the successor of Charlemagne in marriage. And her father, the proud Austrian emperor, was willing to give her up to his conqueror from reasons of state, and from policy and expediency. To all appearance it was no sacrifice to Marie Louise to be transferred from the dull court of Vienna to the splendid apartments of the Tuileries, to be worshipped by the brilliant marshals and generals who had conquered Europe, and to be crowned as empress of the French by the Pope himself. Had she been a nobler woman, she might have hesitated and refused; but she was vain and frivolous, and was overwhelmed by the glory with which she was soon to be surrounded.

Napoleon Informs Empress Josephine of His Intention to Divorce Her After the painting by Eleuterio Pagliano

And yet the marriage was a delicate affair, and difficult to be managed. It required all the tact of an arch-diplomatist. So Prince Metternich was sent to Paris to bring it about. In fact, it was he more than any one else who for political reasons favored this marriage. Napoleon was exceedingly gracious, while Metternich had his eyes and ears open. He even dared to tell the Emperor many unpleasant truths. The affair, however, was concluded; and after Napoleon’s divorce from Josephine, in 1810, the Austrian princess became empress of the French.

One thing was impressed on the mind of Metternich during the festivities of this second visit to Paris; and that was that during the year 1811 the peace of Europe would not be disturbed. Napoleon was absorbed with the preparations for the invasion of Russia,–the only power he had not subdued, except England, and a power in secret coalition with both Prussia and Austria. His acquisitions would not be secure unless the Colossus of the North was hopelessly crippled. Metternich saw that the campaign could not begin till 1812, and that the Emperor had need of all the assistance he could get from conquered allies. He saw also the mistakes of Napoleon, and meant to profit by them. He anticipated for that daring soldier nothing but disaster in attempting to battle the powers of Nature at such a distance from his capital. He perceived that Napoleon was alienating, in his vast schemes of aggrandizement, even his own ministers, like Talleyrand and Fouché, who would leave him the moment they dared, although his marshals and generals might remain true to him because of the enormous rewards which he had lavished upon them for their military services. He knew the discontent of Italy and Poland because of unfulfilled promises. He knew the intense hatred of Prussia because of the humiliations and injuries Napoleon had inflicted on her. Metternich was equally aware of the hostility of England, although Pitt had passed away; and he despised the arrogance of a man who looked upon himself as greater than destiny. “It is an evidence of the weakness of the human understanding,” said the infatuated conqueror, “for any one to dream of resisting me.”

So Metternich, after the marriage ceremony and its attendant festivities, foreseeing the fall of the conqueror, retired to his post at Vienna to complete his negotiations, and make his preparations for the renewal of the conflict, which he now saw was inevitable. His work was to persuade Prussia, Russia, and the lesser Powers, of the absolute necessity of a sincere and cordial alliance to make preparations for the conflict to put down, or at least successfully to resist, the common enemy,–the ruthless and unscrupulous disturber of the peace of Europe; not to make war, but to prepare for war in view of contingencies; and this not merely to preserve the peace of Europe, but to save themselves from ruin. All his confidential letters to his sovereign indicate his conviction that the throne of Austria was in extreme danger of being subverted. All his despatches to ambassadors show that affairs were extremely critical. His policy, in general terms, was pacific; he longed for peace on a settled basis. But his policy in the great crisis of 1811 and 1812 was warlike,–not for immediate hostilities, but for war as soon as it would be safe to declare it. It was his profound conviction that a lasting peace was utterly impossible so long as Napoleon reigned; and this was the conviction also of Pitt and Castlereagh of England and of the Prussian Hardenberg.

The main trouble was with Prussia. Frederick William III. was timid, and considering the intense humiliation of his subjects and the overpowering ascendency of Napoleon, saw no hope but in submission. He was afraid to make a move, even when urged by his ministers. Indeed, he had in 1808 exiled the greatest of them, Stein, at the imperious demand of the French emperor,–sending him to a Rhenish city, whence he was soon after compelled to lead a fugitive life as an outlaw. It is true the king did not like Stein, and saw him go without regret. He could not endure the overshadowing influence of that great man, and was offended by his brusque manners and his plain speech. But Stein saw things as Metternich saw them, and had when prime minister devoted himself to administrative and political reforms. Prince Hardenberg, the successor of Stein, was easily convinced of Metternich’s wisdom; for he was a patriot and an honest man, though loose in his private morals in some respects. Metternich had an ally, too, in Schornhurst, who was remodelling the whole military system of Prussia.

The king, however, persisted in his timid policy until the Russian campaign,–a course which, singularly enough, proved the wisest in his circumstances. When at last the king yielded, all Prussia arose with unbounded enthusiasm to engage in the war of liberation; Prussia needed no urging when actually invaded; Austria openly threw off her conservative appearance of armed neutrality: and the coalition for which Metternich had long been laboring, and of which he was the life and brain, became a reality. The battle of Leipsic settled the fate of Napoleon.

Even before that fatal battle was fought, however, Napoleon, had he been wise, might have saved himself. If he had been content in 1812 to spend the winter in Smolensk, instead of hurrying on to Moscow, the enterprise might not have been disastrous; but after his retreat from Russia, with the loss of the finest army that Europe ever saw, he was doomed. Yet he could not brook further humiliation. He resolved still to struggle. “It may cost me my throne,” said he, “but I will bury the world beneath its ruins.” He marched into Germany, in the spring of 1813, with a fresh army of three hundred and fifty thousand men, replacing the half million he had squandered in Russia. Metternich shrank from further bloodshed, but clearly saw the issue. “You may still have peace,” said he in an audience with Napoleon. “Peace or war lie in your own hands; but you must reduce your power, or you will fail in the contest.” “Never!” replied Napoleon; “I shall know how to die, but I will not yield a handbreadth of soil.” “You are lost, then,” said the Austrian chancellor, and withdrew. “It is all over with the man,” said Metternich to Berthier, Napoleon’s chief of staff; and he turned to marshal the forces of his empire. A short time was given Napoleon to reconsider, but without effect. At twelve o’clock, Aug. 10, 1813, negotiations ceased; the beacon fires were lighted, and hostilities recommenced. During the preparations for the Russian campaign, Austria had been neutral and the rest of Germany submissive; but now Russia, Prussia, and Austria were allied, by solemn compact, to fight to the bitter end,–not to ruin France, but to dethrone Napoleon.

The allied monarchs then met at Toplitz, with their ministers, to arrange the plan of the campaign,–the Austrian armies being commanded by Prince Schwartzenberg, and the Prussians by Blücher. Then followed the battle of Leipsic, on the 16th to the 18th of October, 1813,–“the battle of the nations,” it has been called,–and Napoleon’s power was broken. Again the monarchs, with their ministers, met at Basle to consult, and were there joined by Lord Castlereagh, who represented England, the allied forces still pursuing the remnants of the French army into France. From Basle the conference was removed to the heights of the Vosges, which overlooked the plains of France. On the 1st of April, 1814, the allied sovereigns took up their residence in the Parisian palaces; and on April 4 Napoleon abdicated, and was sent to Elba. He still had twelve thousand or fifteen thousand troops at Fontainebleau; but his marshals would have shot him had he made further resistance. On the 4th of May Louis XVIII. was seated on the throne of his ancestors, and Europe was supposed to be delivered.

Considering the evils and miseries which Napoleon had inflicted on the conquered nations, the allies were magnanimous in their terms. No war indemnity was even asked, and Napoleon in Elba was allowed an income of six million francs, to be paid by France.

After the leaders of the allies had settled affairs at Paris, they reassembled at Vienna,–ostensibly to reconstruct the political system of Europe and secure a lasting peace; in reality, to divide among the conquerors the spoils taken from the vanquished. The Congress of Vienna,–in session from November, 1814, to June, 1815,–of which Prince Metternich was chosen president by common consent, was one of the grandest gatherings of princes and statesmen seen since the Diet of Worms. There were present at its deliberations the Czar of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the kings of Prussia, Denmark, Bavaria, and Würtemberg, and nearly every statesman of commanding eminence in Europe. Lord Castlereagh represented England; Talleyrand represented the Bourbons of France; and Hardenberg, Prussia. Von Stein was also present, but without official place. Besides these was a crowd of petty princes, each with attachés. Metternich entertained the visitors in the most lavish and magnificent manner. The government, though embarrassed and straitened by the expense of the late wars, allowed £10,000 a day, equal perhaps in that country and at that time to £50,000 to-day in London. Nothing was seen but the most brilliant festivities, incessant balls, fêtes, and banquets. The greatest actors, the greatest singers, and the greatest dancers were allured to the giddy capital, never so gay before or since. Beethoven was also there, at the height of his fame, and the great assembly rooms were placed at his disposal.

The sittings of the Congress, in view of the complicated questions which had to be settled, did not regularly begin till November. The meetings at first were harmonious; but ere long they became acrimonious, as the views of the representatives of the four great powers–Russia, Austria, England, and Prussia–were brought to light. They all, except England, claimed enormous territories as a compensation for the sacrifices they had made. Talleyrand at first was excluded from the conferences; but his wonderful skill as a diplomatist soon made his power felt. He was the soul of intrigue and insincerity. All the diplomatists were at first wary and prudent, then greedy and unscrupulous. Violent disputes arose. The Emperor Alexander openly quarrelled with Metternich, and refused to be present at his parties, although they had been on the most friendly terms.

In the division of the spoils, the Czar claimed the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, to be nominally under the rule of a sovereign, but really to be incorporated with his vast empire. Metternich resisted this claim with all the ability he had, as bringing Russia too dangerously near the frontiers of Austria; but Alexander had laid Prussia under such immense obligations that Frederick William supported his claims,–with the mutual understanding, however, that Prussia should annex the kingdom of Saxony, since Saxony had supported Napoleon. The plenipotentiaries were in such awe of the vast armies of the Czar, that they were obliged to yield to this wicked annexation; and Poland–once the most powerful of the mediaeval kingdoms of Europe–was wiped out of the map of independent nations. This acquisition by far outbalanced all the expenses which Alexander had incurred during the war of liberation. It made Russia the most powerful military empire in the world.

Although Prussia and Austria had been, since the times of Frederic the Great, in perpetual rivalry, the greatness of the common danger from such a warlike neighbor now induced Metternich to make every overture to Prussia to prevent a possible calamity to Germany; but Frederick William was obstinate, and his league with Alexander could not be broken. It appears, from the memoirs of Metternich, that it had been for a long time his desire to unite Prussia and Austria in a firm alliance, in order to protect Germany in case of future wars. That was undoubtedly his true policy. It was the policy fifty years later of Bismarck, although he was obliged to fight and humble Austria before he could consummate it. With Russia on one side and France on the other, the only hope of Germany is in union. But this aim of the great Austrian statesman was defeated by the stupidity and greed of the Prussian king, and by his interested friendship with “the autocrat of all the Russias.” Alexander got Poland, with an addition of about four million subjects to his empire.

A greater resistance was made to the outrageous claims of Prussia. She wanted to annex the whole of Saxony and important provinces on the Rhine, which would have made her more powerful than Austria. Neither Metternich nor Talleyrand nor Castlereagh would hear of this crime; and so angry and threatening were the disputes in the Congress that a treaty was signed by England, France, and Austria for an offensive and defensive alliance against Prussia and Russia, in case the claims of Prussia were persisted in. After the combination of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and England against Napoleon, there was imminent danger of war breaking out between these great Powers in the matter of a division of spoils. In rapacity and greed they showed themselves as bad as Napoleon himself.

Prussia, however, was the most greedy and insatiable of all the contracting parties. She always has been so since she was erected into a kingdom. The cruel terms exacted by Bismarck and Moltke in their late contest with France indicate the real animus of Prussia. The conquerors would have exacted ten milliards instead of five, as a war indemnity, if they had thought that France could pay it. They did not dare to carry away the pictures of the Louvre, nor perhaps did those iron warriors care much for them; but they did want money and territory, and were determined to get all they could. Prussia was a poor country, and must be enriched any way by the unexpected spoils which the fortune of war threw into her hands.

This same rapacity was seen at the Congress of Vienna; but the opposition to it was too great to risk another war, and Prussia, at the entreaty of Alexander, abated some of her demands, as did also Russia her own. The result was that only half of Saxony was ceded to Prussia, raising the subjects of Prussia to ten millions. The tact and firmness of Talleyrand and Castlereagh had prevented the utter absorption of Saxony in the new military monarchy. Talleyrand, whose designs could never be fathomed by the most astute of diplomatists, had succeeded also in isolating Russia and Prussia from the rest of Europe, and raising France into a great power, although her territories were now confined to the limits which had existed in 1792. He had succeeded in detaching Austria and the southern States of Germany from Prussia. He had split Germany into two rival powers, just what Louis Napoleon afterwards aspired to do, hoping to derive from their mutual jealousies some great advantage to France in case of war. Neither of them, however, realized the intense common love of both Austria and Prussia, and indeed of all the German States at heart, for “Fatherland,” needing only the genius of a very great man finally to unite them together in one great nation, impossible to be hereafter vanquished by any single power.

Austria retained for her share Lombardy, Venice, Parma, Placentia,–the finest part of Italy, that which was known in the time of Julius Caesar as Cisalpine Gaul. She did not care for the Low Countries, which formed a part of the old empire of Charles V., since to keep that territory would cost more than it would pay. She also received from Bavaria the Tyrol. As further results of the Congress of Vienna, the Netherlands and Holland were united in one kingdom, under a prince of the house of Nassau; Naples returned to the rule of the Bourbons; Genoa became a part of Piedmont. The petty independent States of Germany (some three hundred) were united into a confederation of thirty-seven, called the German Confederacy, to afford mutual support in time of war, and to be directed by a Diet, in which Austria and Prussia were to have two votes each, while Bavaria, Würtemberg, and Hanover were to have one vote each. Thus, Prussia and Austria had four votes out of seven; which practically gave to these two powers, if they chose to unite, the control of all external relations. As to internal affairs, the legislative power was vested in representatives from all the States, both small and great. It will be seen that the higher interests of Germany were not considered in this Congress at all, attention being directed solely to a division of spoils.

But while the Congress was dividing between the princes who composed it its acquisition of territory by conquest, and quarrelling about their respective shares like the members of a family that had come into a large fortune, news arrived of the escape of Napoleon from Elba, after a brief ten months’ detention, the adherence to him of the French army, and the consequent dethronement of Louis XVIII. The Congress at once dispersed, forgetting all its differences, while the great monarchs united once more in pouring such an avalanche of troops into France and Belgium that Napoleon stood no chance of retaining his throne, whatever military genius he might display. After his defeat at Waterloo the allies occupied Paris, and this time exacted a large war indemnity of £40,000,000, and left an army of occupation of one hundred and fifty thousand men in France until the money should be paid. They also returned to their owners the pictures of the Louvre which Napoleon had taken in his various conquests.

It was while the allies were in Paris settling the terms of the second peace, that what is called the “Holy Alliance” was formed between Alexander, Frederick William, and Francis (to whom were afterward added the kings of France, Naples, and Spain), which had for its object the suppression of liberal ideas throughout the Continent, in the name of religion. Some of these monarchs were religious men in their way,–especially the Czar, who had been much interested in the spread of Christianity, and the king of Prussia; but even these men thought more of putting down revolutionary ideas than they did of the triumphs of religion.

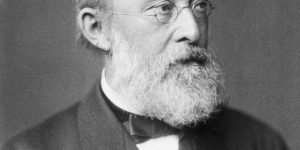

Prince Clemens Wenzel von Metternich, painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence

We must, however, turn our attention to Metternich as the administrator of a large empire, rather than as a diplomatist, although for thirty years after this his hand was felt, if not seen, in all the political affairs of Europe. He was now forty-four years of age, in the prime of his strength and the fulness of his fame,–a prince of the empire, chancellor and prime minister to the Emperor Francis. On his shoulders were imposed the burdens of the State. He ruled with delegated powers indeed, but absolutely. The master whom he served was weak, but was completely in accord with Metternich on all political questions. He of course submitted all important documents to the emperor, and requested instructions; but all this was a matter of form. He was allowed to do as he pleased. He was always exceedingly deferential, and never made himself disagreeable to his sovereign, who could not do without him. From first to last they were on the most friendly terms with each other, and there was no jealousy of his power on the part of the emperor. The chancellor was a gentleman, and had extraordinary tact. But his labors were prodigious, and gave him no time for pleasure, or even social intercourse, which finally became irksome to him. He was too busy with public affairs to be a great scholar, and was not called upon to make speeches, as there was no deliberative assembly to address. Nor was he a national idol. He lived retired in his office, among ministers and secretaries, and appeared in public as little as possible.

After the final dethronement of Napoleon, the policy of Metternich with reference to foreign powers was pacific. He had seen enough of war, and it had no charm for him. War had brought Germany to the verge of political ruin. All his efforts as chancellor were directed to the preservation of peace and the balance of power among all nations. At the close of the great European struggle the finances of all the German States were alike disordered, and their industries paralyzed. Compared with France and England Germany was poor, and wages for all kinds of labor were small. It became Metternich’s aim to develop the material resources of the empire, which could be best done in time of peace. Austria, accordingly, took part in no international contest for fifty years, except to preserve her own territories. Metternich did not seem to be ambitious of further territorial aggrandizement for his country; it required all his talents to preserve what she had. Indeed, the preservation of the status quo everywhere was his desire, without change, and without progress. He was a conservative, like the English Lord Eldon, who supported established institutions because they were established; and any movement or any ideas which interrupted the order of things were hateful to him, especially agitations for greater political liberty. A constitutional government was his abhorrence.

Hence, the policy of Metternich’s home rule was fatal to all expansion, to all emancipating movements, to all progress, to everything which looked like popular liberty. Men might smoke, drink beer, attend concerts and theatres, amuse themselves in any way they pleased, but they should not congregate together to discuss political questions; they should not form clubs or societies with political intent of any kind; they should not even read agitating tracts and books. He could not help their thinking, but they should not criticise his government. They should be taught in schools directed by Roman Catholic priests, who were good classical scholars, good mathematicians, but who knew but little and cared less about theories of political economy, or even history unless modified to suit religious bigots of the Mediaeval type. He maintained that men should be contented with the sphere in which they were born; that discontent was no better than rebellion against Providence; that any change would be for the worse. He had no liking for universities, in which were fomented liberal ideas; and those professors who sought to disturb the order of things, or teach new ideas,–anything to make young scholars think upon anything but ordinary duties,–were silenced or discharged or banished. The word “rights” was an abomination to him; men, he thought, had no rights,–only duties. He disliked the Press more than he did the universities. It was his impression that it was antagonistic to all existing governments; hence he fettered the Press with restrictions, and confined it to details of little importance. He would allow no comments which unsettled the minds of readers. In no country was the censorship of the Press more inexorable than in Austria and its dependent States. All that spies and a secret police and priests could do to ferret out associations which had in view a greater liberty, was done; all that soldiers could do to suppress popular insurrection was effected,–and all in the name of religion, since he looked upon free inquiry as logically leading to scepticism, and scepticism to infidelity, and infidelity to revolution.

In the Catholic sense Metternich was a religious man, since he recognized in the Roman Catholic Church the conservation of all that is valuable in society, in government, and even in civilization. He brought Catholics to his aid in cementing political despotism, for “Absolutism and Catholicism,” as Sir James Stephen so well said, “are but convertible terms.” Accordingly, he brought back the Jesuits, and restored them to their ancient power and wealth. He formed the strictest union with the Pope. He rewarded ecclesiastics, and honored the great dignitaries of the established church as his most efficient and trusted lieutenants in the war he waged on human liberty.

But I must allude to some of the things which gave this great man trouble. Of course nothing worried him so much as popular insurrections, since they endangered the throne, and opposed the cherished ends of his life. As early as 1817, what he called “sects” disturbed central Europe. These were a class of people who resembled the Methodists of England, and the followers of Madam von Krüdener in Russia,–generally mystics in religion, who practised the greatest self-denial in this world to make sure of the promises of the next. The Kingdom of Würtemberg, the Grand Duchy of Baden, and Suabia were filled with these people,–perfectly harmless politically, yet with views which Metternich considered an innovation, to be stifled in the beginning. So of Bible societies; he was opposed to these as furnishing a class of subjects for discussion which brought up to his mind the old dissertations on “the rights of man.” “The Catholic Church,” he writes to Count Nesselrode, the Russian minister, “does not encourage the universal reading of the Bible, which should be confined to persons who are calm and enlightened.” But he goes on to say that he himself at forty-five reads daily one or two chapters, and finds new beauties in them, while at the age of twenty he was a sceptic, and found it difficult not to think that the family of Lot was unworthy to be saved, Noah unworthy to have lived, Saul a great criminal, and David a terrible man; that he had tried to understand everything, but that now he accepts everything without cavil or criticism. Truly, a Catholic might say, “See the glorious peace and repose which our faith brings to the most intellectual of men!”

In 1819 an event occurred, of no great importance in itself, but which was made the excuse for increased stringency in the suppression of liberal sentiments throughout Germany. This was the assassination of Von Kotzebue, the dramatic author, at Manheim, at the hands of a fanatic by the name of Sand. Kotzebue had some employment under the Russian government, and was supposed to be a propagandist of the views of the Czar, who had lately become exceedingly hostile to all emancipating movements. In the early part of his reign Alexander was called a Jacobin by Metternich, who despised his philanthropical and sentimental theories, and his energetic labors in behalf of literature, educational institutions, freer political conditions, etc.; but when Napoleon was sent to St. Helena, the Russian ruler, wearied with great events and dreading revolutionary tendencies, changed his opinions, and was now leagued with the King of Prussia and the Emperor of Austria in supporting the most stringent measures against all reformers. Sand was a theological student in the University of Jena, who thought he was doing God’s service by removing from the earth with his assassin’s dagger a vile wretch employed by the Russian tyrant to propagate views which mocked the loftiest aspirations of mankind. The murder of Kotzebue created an immense sensation throughout Europe, and was followed by increased rigor on the part of all despotic governments in muzzling the press, in the suppression of public meetings of every sort, and especially in expelling from the universities both students and professors who were known or even supposed to entertain liberal ideas. Metternich went so far as to write a letter to the King of Prussia urging him to disband the gymnasia, as hotbeds of mischief. His influence on this monarch was still further seen in dissuading him to withhold the constitution promised his subjects during the war of liberation. He regarded the meeting of a general representation of the nation as scarcely less evil than democratic violence, and his hatred of constitutional checks on a king was as great as of intellectual independence in a professor at a gymnasium. Universities and constituent assemblies, to him, were equally fatal to undisturbed peace and stability in government.

In the midst of these efforts to suppress throughout Germany all agitating political ideas and movements, the news arrived of the revolution in Naples, July, 1820, effected by the Carbonari, by which the king was compelled to restore the constitution of 1813, or abdicate. Metternich lost no time in assembling the monarchs of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, with their principal ministers, to a conference or congress at Troppau, with a view of putting down the insurrection by armed intervention. The result is well known. The armies of Austria and Russia–170,000 men–restored the Neapolitan tyrant to his throne; while he, on his part, revoked the constitution he had sworn to defend, and affairs at Naples became worse than they were before. In no country in the world was there a more execrable despotism than that exercised by the Bourbon Ferdinand. The prisons were filled with political prisoners; and these prisons were filthy, without ventilation, so noisome and pestilential that even physicians dared not enter them; while the wretched prisoners, mostly men of culture, chained to the most abandoned and desperate murderers and thieves, dragged out their weary lives without trial and without hope. And this was what the king, supported and endorsed by Metternich, considered good government to be.

The following year saw an insurrection in Piedmont, when the patriotic party hoped to throw all Northern Italy upon the rear of the Austrians, but which resulted, as will be treated elsewhere, in a sad collapse. The victory of absolutism in Italy was complete, and all people seeking their liberties became the object of attack from the three great Powers, who obeyed the suggestions of the Austrian chancellor,–now unquestionably the most prominent figure in European politics. He had not only suppressed liberty in the country which he directly governed, but he had united Austria, Prussia, and Russia in a war against the liberties of Europe, and this under the guise of religion itself.

Metternich now thought he had earned a vacation, and in the fall of 1821 he made a visit to Hanover. He had previously visited Italy with the usual experience of cultivated Germans,–unbounded admiration for its works of art and sunny skies and historical monuments. He was as enthusiastic as Madame de Staël over St. Peter’s and the Pantheon. In his private letters to his wife and children, so simple, so frank, so childlike in his enjoyment, no one would suppose he was the arch and cruel enemy of all progress, with monarchs for his lieutenants, and governors for his slaves. His journey to Hanover was a triumphant procession. The King George IV. embraced him with that tenderness which is usual with monarchs when they meet one another, and in the fulsomeness of his praises compared him to all the great men of antiquity and of modern times,–Caesar, Cato, Gustavus Adolphus, Marlborough, Pitt, Wellington, and the whole catalogue of heroes. On his return journey to Vienna, Metternich stopped to rest himself a while at Johannisberg, the magnificent estate on the Rhine which the emperor had given him, near where he was born, and where he had stored away forty huge casks of his own vintage, worth six hundred ducats a cask, for the use of monarchs and great nobles alone. From thence he proceeded to Frankfort, a beautiful but to him a horrible town, I suppose, because it was partially free; and while there he took occasion to visit five universities, at all of which he was received as a sort of deity,–the students following his carriage with uncovered heads, and with cheers and shouts, curious to see what sort of a man it was who had so easily suppressed revolution in Italy, and who ruled Germany with such an iron hand.

And yet while Metternich so completely extinguished the fires of liberty in the countries which he governed, he was doomed to see how hopeless it was to do the same in other lands by mere diplomatic intrigues. In 1822 the Spanish revolution broke out; and a year after came the Greek revolution, with all its complications, ending in a war between Russia and Turkey. From this he stood aloof, since if he helped the Turks to put down insurrection he would offend the Emperor Alexander, thus far his best ally, and commit Austria to a war from which he shrank. It was his policy to preserve his country from entangling wars. It was as much as he could do to preserve order and law in the various States of Germany, at the cost of all intellectual progress. But he watched the developments of liberty in other parts of Europe with the keenest interest, and his correspondence with the different potentates–whether monarchs or their ministers–is very voluminous, and was directed to the support of absolutism, in which alone he saw hope for Europe. The liberal views of the English Canning gave Metternich both solicitude and disgust; and he did all he could to undermine the influence of Capo D’Istrias, the Greek diplomatist, with his imperial master the Czar. He hated any man who was politically enlightened, and destroyed him if he could. The event in his long reign which most perplexed him and gave him the greatest solicitude was the revolution in France in 1830, which unseated the Bourbons, and established the constitutional government of Louis Philippe; and this was followed by the insurrection of the Netherlands, revolts in the German States, and the Polish revolution. With the year 1830 began a new era in European politics,–a period of reform, not always successful, but enough to show that the spirit of innovation could no longer be suppressed; that the subterranean fires of liberty would burst forth when least expected, and overthrow the strongest thrones.

But amid all the reforms which took place in England, in France, in Belgium, in Piedmont, Austria remained stationary, so cemented was the power of Metternich, so overwhelming was his influence,–the one central figure in Germany for eighteen years longer. In 1835 the Emperor Francis died, recommending to his son and successor Ferdinand to lean on the powerful arm of the chancellor, and continue him in great offices. Nor was it until the outbreak in Vienna in 1848, when emperor and minister alike fled from the capital, that the official career of Metternich closed, and he finally retired to his estates at Johannisberg to spend his few declining years in leisure and peace.

For forty years Metternich had borne the chief burdens of the State. For forty years his word was the law of Germany. For forty years all the cabinets of continental Europe were guided more or less by his advice; and his advice, from first to last, was uniform,–to put down popular movements and uphold absolutism at any cost, and severely punish all people, of whatever rank or character, who tempted the oppressed to shake off their fetters, or who dared to give expression to emancipating ideas, even in the halls of universities.

In view of the execrable tyranny, both political and religious, which Metternich succeeded in establishing for thirty years, it is natural for an ordinary person to look upon him as a monster,–hard, cruel, unscrupulous, haughty, gloomy; a sort of Wallenstein or Strafford, to be held in abhorrence; a man to be assassinated as the enemy of mankind.

But Metternich was nothing of the sort. As a man, in all his private relations he was amiable, gentle, and kind to everybody, and greatly revered by domestic servants and public functionaries. By his imperial master he was treated as a brother or friend, rather than as a minister; while on his part he never presumed on any liberties, and seemed simply to obey the orders of his sovereign,–orders which he himself suggested, with infinite tact and politeness; unlike Stein and Bismarck, who were overbearing and rude even in the presence of the sovereign and court. Metternich had better manners and more self-control. Indeed, he was the model of a gentleman wherever he went. He was the hardest worked man in the empire; and he worked from the stimulus of what he conceived to be his duty, and for the welfare of the country, as he understood it. Though one of the richest men in Austria, and of the highest social rank, he lived in frugal simplicity, despising pomp and extravagance alike. His highest enjoyment, outside the society of his family, was music. The whole realm of art was his delight; but he loved Nature more even than art. He enjoyed greatly the repose of his own library,–an apartment eighteen feet high, and containing fifteen thousand volumes. The only unamiable thing about Metternich was his fear of being bored. He maintained that it was impossible to find over six interesting men in any company whatever. With people whom he trusted he was unusually frank and free-spoken. With diplomatists he wore a mask, and made it a point to conceal his thoughts. He deceived even Napoleon. No one could penetrate his intentions. Under a smooth and placid countenance, unruffled and calm on all occasions, he practised when he pleased the profoundest dissimulation; and he dissimulated by telling the truth oftener than by concealing it. He knew what the ars celare artem meant. When he could find leisure he was fond of travelling, especially in Italy; but he hated and avoided the discomforts of travel. If he made distant journeys he travelled luxuriously, and wherever he went he was received with the greatest honors. At Rome the Pope treated him as a sovereign. The Czar Alexander commanded his magnates to give to him the same deference that they gave to himself.

While the world regarded Metternich as the most fortunate of men, he yet had many sorrows and afflictions, which saddened his life. He lost two wives and three of his children, to all of whom he was devotedly attached, yet bore the loss with Christian resignation. He found relief in work, and in his duties. There were no scandals in his private life. He professed and seemed to feel the greatest reverence for religion, in the form which had been taught him. He detested vulgarity in every shape, as he did all ordinary vices, from which he was free. He was self-conscious, and loved attention and honors, but was not a slave to them, like most German officials. Nothing could be more tender and affectionate than his letters to his mother, to his wife, and to his daughters. His father he treated with supreme reverence. No public man ever gave more dignity to domestic pleasures. “The truest friends of my life,” said he, “are my family and my master;” and to each he was equally devoted. On the death of his second wife, in 1829, he writes,–

“I feel this misfortune most deeply. I have lost everything for the remainder of my days. The other world is daily more and more peopled with beings to whom I am united by the closest ties of affection. I too shall take my place there, and I shall disengage myself from this life with all the less regret. My only relief is in work. I am at my desk by nine in the morning. I leave it at five, and return to it at half-past six, and work till half-past ten, when I receive visitors till midnight.”

Time, however, brought its relief, and in 1831 he married the Princess Melanie, and his third marriage was as happy as the others appear to have been. In the diary of this wife, December 31, I read:–

“We supped at midnight, and exchanged good wishes for the new year. May God long preserve to me my good, kind Clement, and illuminate him with His divine light. It touches me to see the pleasure it gives him to talk with me on business, and read to me what he writes.”

Such was the great Austrian statesman in his private life,–a dutiful son, a loving and devoted husband, an affectionate father, a faithful servant to his emperor, a kind master to his dependants, a courteous companion, a sincere believer in the doctrines of his church, a man conscientious in the discharge of duties, and having at heart the welfare of his country as he understood it, amid innumerable perils from foreign and domestic foes. As a statesman he was vigilant, sagacious, experienced, and devoted to the interests of his imperial master.

But what were Metternich’s services, by which great men claim to be judged? He could say that he was the promoter of law and order; that he kept the nation from entangling alliances with foreign powers; that he was the friend of peace, and detested war except upon necessity; that he developed industrial resources and wisely regulated finances; that he secured national prosperity for forty years after desolating wars; that he never disturbed the ordinary vocations of the people, or inflicted unnecessary punishments; and that he secured to Austria a proud pre-eminence among the nations of Europe.

But this was all. Metternich did nothing for the higher interests of Germany. He kept it stagnant for forty years. He neither advanced education, nor philanthropy, nor political economy. He was the unrelenting foe of all political reforms, and of all liberal ideas. What we call civilization, beyond amusements and pleasures and the ordinary routine of business, owes to him nothing,–not even codes of law, or enlightened principles of government. Judged by his services to humanity, Metternich was not a great man. His highest claims to greatness were in a vigorous administration of public affairs and diplomatic ability in his treatment of foreign powers, but not in far-reaching views or aims. As a ruler he ranks no higher than Mazarin or Walpole or Castlereagh, and far below Canning, Peel, Pitt, or Thiers. Indeed, Metternich takes his place with the tyrants of mankind, yet showing how benignant, how courteous, how interesting, and even religious and beloved, a tyrant can be; which is more than can be said of Richelieu or Bismarck, the only two statesmen with whom he can be compared,–all three ruling with absolute power delegated by irresponsible and imperial masters, like Mordecai behind the throne of Xerxes, or Maecenas at the court of Augustus.

Authorities.

The greatest authority is the Autobiography of Metternich; but Alison’s History, though dull and heavy, and marked by Tory prejudices, is reliable. Fyffe may be read with profit in his recent history of Modern Europe; also Müller’s Political History of Recent Times. The Annual Register is often quoted by Alison. Schlosser’s History of Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is a good authority.