Saint Paul : The Spread of Christianity – Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets

Abraham : Religious Faith

Joseph : Israel in Egypt

Moses : Jewish Jurisprudence

Samuel : Israel Under Judges

David : Israelitish Conquests

Solomon : Glory of The Monarchy

Elijah : Division of The Kingdom

Isaiah : National Degeneracy

Jeremiah : Fall of Jerusalem

Judas Maccabaeus : Restoration of The Jewish Commonwealth

Saint Paul : The Spread of Christianity

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Birth and early days of Saul

His Phariseeism

His persecution of the Christians

His wonderful conversion

His leading idea

Saul a preacher at Damascus

Saul’s visit to Jerusalem

Saul in Tarsus

Saul and Barnabas at Antioch

Description of Antioch

Contribution of the churches for Jerusalem

Saul and Barnabas at Jerusalem

Labors and discouragements

Saul and Barnabas at Cyprus

Saul smites Elymas the sorcerer

Missionary travels of Paul

Paul converts Timothy

Paul at Lystra and Derbe

Return of Paul to Antioch

Controversy about circumcision

Bigotry of the Jewish converts

Paul again visits Jerusalem

Paul and Barnabas quarrel

Paul chooses Silas for a companion

Paul and Silas visit the infant churches

Tact of Paul

Paul and Luke

The missionaries at Philippi

Paul and Silas at Thessalonica

Paul at Athens

Character of the Athenians

The success of Paul at Athens

Paul goes to Corinth

Paul led before Gallio

Mistake of Gallio

Paul’s Epistle to the Thessalonians

Paul at Ephesus

The Temple of Diana

Excessive labors of Paul at Ephesus

Paul’s first Epistle to the Corinthians

Popularity of Apollos

Second Epistle to the Corinthians

Paul again at Corinth

Epistles to the Galatians and to the Romans

The Pauline theology

Paul’s last visit to Jerusalem

His cold reception

His arrest and imprisonment

The trial of Paul before Felix

Character of Felix

Paul kept a prisoner by Felix

Paul’s defence before Festus

Paul appeals to Caesar

Paul preaches before Agrippa

His voyage to Italy

Paul’s life at Rome

Character of Paul

His magnificent services

His triumphant death

Saint Paul : The Spread of Christianity

DIED, ABOUT 67 A.D.

The Scriptures say but little of the life of Saul from the time he was a student, at the age of fifteen, at the feet of Gamaliel, one of the most learned rabbis of the Jewish Sanhedrim at Jerusalem, until he appeared at the martyrdom of Stephen, when about thirty years of age.

Saul, as he was originally named, was born at Tarsus, a city of Cilicia, about the fourth year of our era. His father was a Jew, a pharisee, and a man of respectable social position. In some way not explained, he was able to transmit to his son the rights of Roman citizenship,–a valuable inheritance, as it proved. He took great pains in the education of his gifted son, who early gave promise of great talents and attainments in rabbinical lore, and who gained also some knowledge, although probably not a very deep one, of the Greek language and literature. Saul’s great peculiarity as a young man was his extreme pharisaism,–devotion to the Jewish Law in all its minuteness of ceremonial rites. We gather from his own confessions that at that period, when he was engrossed in the study of the Jewish scriptures and religious institutions, he was narrow and intolerant, and zealous almost to fanaticism to perpetuate ritualistic conventionalities and the exclusiveness of his sect. He was austere and conscientious, but his conscience was unenlightened. He exhibited nothing of that large-hearted charity and breadth of mind for which he was afterward distinguished; he was in fact a bitter persecutor of those who professed the religion of Jesus, which he detested as an innovation. His morality being always irreproachable, and his character and zeal giving him great influence, he was sent to Damascus, with authority to bring to Jerusalem for trial or punishment those who had embraced the new faith. He is supposed to have been absent from Jerusalem during the ministry of our Lord, and probably never saw him who was despised and rejected of men. We are told that Saul, in the virulence of his persecuting spirit, consented to the death of Stephen, who was no ignorant Galilean, but a learned Hellenist; nor is there evidence that the bitter and relentless young pharisee was touched either by the eloquence or blameless life or terrible sufferings of the distinguished martyr.

The next memorable event in the life of Saul–at that time probably a member of the Jewish Sanhedrim–was his conversion to Christianity, as sudden and unexpected as it was profound and lasting, while on his way to Damascus on the errand already mentioned. The sudden light from heaven which exceeded in brilliancy the torrid midday sun, the voice of Jesus which came to the trembling persecutor as he lay prostrate on the ground, the blindness which came upon him–all point to the supernatural; for he was no inquirer after truth like Luther and Augustine, but bent on a persistent course of cruel persecution. At once he is a changed man in his spirit, in his aims, in his entire attitude toward the followers of the Nazarene. The proud man becomes as docile and humble as a child; the intolerant zealot for the Law becomes broad and charitable; and only one purpose animates his whole subsequent life,–which is to spend his strength, amid perils and difficult labors, in defence of the doctrines he had spurned. His leading idea now is to preach salvation, not by pharisaical works by which no man can be justified, but by faith in the crucified one who was sent into the world to save it by new teachings and by his death upon the cross. He will go anywhere in his sublime enthusiasm, among Jews or among Gentiles, to plant the precious seeds of the new faith in every pagan city which he can reach.

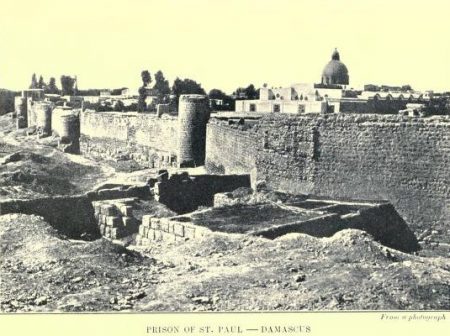

It is thought by Conybeare and Howson, Farrar and others that the new convert spent three years in retirement in Arabia, in profound meditation and communion with God, before the serious labors of his life began as a preacher and missionary. After his conversion it would seem that Saul preached the divinity of Christ with so much zeal that the Jews in Damascus were filled with wrath, and sought to take his life, and even guarded the gates of the city for fear that he might escape. The conspiracy being detected, the friends of Saul put him into a basket made of ropes, and let him down from a window in a house built upon the city wall, so that he escaped, and thereupon proceeded to Jerusalem to be indorsed as a Christian brother. He was especially desirous to see Peter, as the foremost man among the Christians, though James had greater dignity. Peter received him kindly, though not enthusiastically, for the remembrance of his relentless persecutions was still fresh in the minds of the Christians. It was impossible, however, that two such warmhearted, honest, and enthusiastic men should not love each other, when the common leading principle of their lives was mutually understood.

Among the disciples, however, it was only Peter who took Saul cordially by the hand. The other leaders held aloof; not one so much as spoke to him. He was regarded with general mistrust; even James, the Lord’s brother, the first bishop of Jerusalem, would hold no communion with him. At length Joseph, a Levite of Cyprus, afterward called Barnabas,–a man of large heart, who sold his possessions to give to the poor,–recognizing Saul’s sincerity and superior talents, extended to him the right hand of fellowship, and later became his companion in the missionary journeys which he undertook. He used his great influence in removing the prejudices of the brethren, and Saul henceforth was admitted to their friendship and confidence.

Saul at first did not venture to preach in Hebrew synagogues, but sought the synagogue of the Hellenists, in which the voice of Stephen had first been heard. But his preaching was again cut short by a conspiracy to murder him, so fierce was the animosity which his conversion had created among the Jews, and he was compelled to flee. The brethren conducted him to the little coast village of Caesarea, whence he sailed for his native city Tarsus, in Cilicia.

How long Saul remained in Tarsus, and what he did there, we do not know. Not long, probably, for he was sought out by Barnabas as his associate for missionary work in Antioch. It would seem that on the persecution which succeeded Stephen’s death, many of the disciples fled to various cities; and among others, to that great capital of the East,–the third city of the Roman Empire.

Thither Barnabas had gone as their spiritual guide; but he soon found out that among the Greeks of that luxurious and elegant city there were demanded greater learning, wisdom, and culture than he himself possessed. He turned his eyes upon Saul, then living quietly at Tarsus, whose superior tact and trained skill in disputation, large and liberal mind, and indefatigable zeal marked him out as the fittest man he could find as a coadjutor in his laborious work. Thus Saul came to Antioch to assist Barnabas.

No city could have been chosen more suitable for the peculiar talents of Saul than this great Eastern emporium, containing a population of five hundred thousand. I need not speak of its works of art,–its palaces, its baths, its aqueducts, its bridges, its basilicas, its theatres, which called out even the admiration of the citizens of the imperial capital. These were nothing to Saul, who thought only of the souls he could convert to the religion of Jesus; but they indicate the importance and wealth of the population. In this pagan city were half a million people steeped in all the vices of the Oriental world,–a great influx of heterogeneous races, mostly debased by various superstitions and degrading habits, whose religion, so far as they had any, was a crude form of Nature-worship. And yet among them were wits, philosophers, rhetoricians, poets, and satirists, as was to be expected in a city where Greek was the prevailing language. But these were not the people who listened to Saul and Barnabas. The apostles found hearers chiefly among the poor and despised,–artisans, servants, soldiers, sailors,–although occasionally persons of moderate independence became converts, especially women of the middle ranks. Poor as they were, the Christians at Antioch found means to send a large contribution in money to their brethren at Jerusalem, who were suffering from a grievous famine.

A year was spent by Barnabas and Saul at Antioch in founding a Christian community, or congregation, or “church,” as it was called. And it was in this city that the new followers of Christ were first called “Christians,” mostly made up as they were of Gentiles. The missionaries had not much success with the Jews, although it was their custom first to preach in the Jewish synagogues on the Sabbath. It was only the common people of Antioch who heard the word gladly, for it was to them tidings of joy, which raised them above their degradation and misery.

With the contributions which the Christians of Antioch, and probably of other cities, made to their poorer and afflicted brethren, Barnabas and Saul set out for Jerusalem, soon returning however to Antioch, not to resume their labors, but to make preparations for an extended missionary tour. Saul was then thirty-seven years of age, and had been a Christian seven years.

In spite of many disadvantages, such as ill-health, a mean personal appearance, and a nervous temperament, without a ready utterance, Saul had a tolerable mastery of Greek, familiarity with the habits of different classes, and a profound knowledge of human nature. As a widower and childless, he was unincumbered by domestic ties and duties; and although physically weak, he had great endurance and patience. He was courteous in his address, liberal in his views, charitable to faults, abounding in love, adapting himself to people’s weaknesses and prejudices,–a man of infinite tact, the loftiest, most courageous, most magnanimous of missionaries, setting an example to the Xaviers and Judsons of modern times. He doubtless felt that to preach the gospel to the heathen was his peculiar mission; so that his duty coincided with his inclination, for he seems to have been very fond of travelling. He made his journeys on foot, accompanied by a congenial companion, when he could not go by water, which was attended with less discomfort, and was freer from perils and dangers than a land journey.

The first missionary journey of Barnabas and Saul, accompanied by Mark, was to the isle of Cyprus. They embarked at Seleucia, the port of Antioch, and landed at Salamis, where they remained awhile, preaching in the Jewish synagogue, and then traversed the whole island, which is about one hundred miles in length. Whenever they made a lengthened stay, Saul worked at his trade as a sail and tent maker, so as not to be burdensome to any one. His life was very simple and inexpensive, thus enabling him to maintain that independence so essential to self-respect.

No notable incident occurred to the three missionaries until they reached the town of Nea-Paphos, celebrated for the worship of Venus, the residence of the Roman proconsul, Sergius Paulus,–a man of illustrious birth, who amused himself with the popular superstitions of the country. He sought, probably from curiosity, to hear Barnabas and Saul preach; but the missionaries were bitterly opposed by a Jewish sorcerer called Elymas, who was stricken with blindness by Saul, the miracle producing such an effect on the governor that he became a convert to the new faith. There is no evidence that he was baptized, but he was respected and beloved as a good man. From that time the apostle assumed the name of Paul; and he also assumed the control of the mission, Barnabas gracefully yielding the first rank, which till then he had himself enjoyed. He had been the patron of Saul, but now became his subordinate; for genius ever will work its way to ascendency. There are no outward advantages which can long compete with intellectual supremacy.

From Cyprus the missionaries went to Perga, in Pamphylia, one of the provinces of Asia Minor. In this city, famed for the worship of Diana, their stay was short. Here Mark separated from his companions and returned to Jerusalem, much to the mortification of his cousin Barnabas and the grief of Paul, since we have a right to infer that this brilliant young man was appalled by the dangers of the journey, or had more sympathy with his brethren at Jerusalem than with the liberal yet overbearing spirit of Paul.

From Perga the two travellers proceeded to Antioch in Pisidia, in the heart of the high table-lands of the Peninsula, and, according to their custom, went on Saturday to the Jewish synagogue. Paul, invited to address the meeting, set forth the mystery of Jesus, his death, his resurrection, and the salvation which he promised to believers. But the address raised a storm, and Paul retired from the synagogue to preach to the Gentile population, many of whom were favorably disposed, and became converted. The same thing subsequently took place at Philippi, at Alexandria, at Troas, and in general throughout the Roman colonies. But the influence of the Jews was sufficient to secure the expulsion of Paul and Barnabas from the city; and they departed, shaking off the dust from their feet, and turning their steps to Iconium, a city of Lycaonia, where a church was organized. Here the apostles tarried some time, until forced to leave by the orthodox Jews, who stirred up the heathen population against them. The little city of Lystra was the scene of their next labors, and as there were but few Jews there the missionaries not only had rest, but were very successful.

The sojourn at Lystra was marked by the miraculous cure of a cripple, which so impressed the people that they took the missionaries for divinities, calling Barnabas Jupiter, and Paul Mercury; and a priest of the city absolutely would have offered up sacrifices to the supposed deities, had he not been severely rebuked by Paul for his superstition.

At Lystra a great addition was made to the Christian ranks by the conversion of Timothy, a youth of fifteen, and of his excellent mother Eunice; but the report of these conversions reached Iconium and Antioch of Pisidia, which so enraged the Jews of these cities that they sent emissaries to Lystra, zealous fanatics, who made such a disturbance that Paul was stoned, and left for dead. His wounds, however, were not so serious as were supposed, and the next day he departed with Barnabas for Derbe, where he made a long stay. The two churches of Lystra and Derbe were composed almost wholly of heathen.

From Derbe the apostles retraced their steps, A.D. 46, to Antioch, by the way they had come,–a journey of one hundred and twenty miles, and full of perils,–instead of crossing Mount Taurus through the famous pass of the Cilician Gates, and then through Tarsus to Antioch, an easier journey.

One of the noticeable things which marked this first missionary journey of Paul, was the opposition of the Jews wherever he went. He was forced to turn to the Gentiles, and it was among them that converts were chiefly made. It is true that his custom was first to address the Jewish synagogues on Saturday, but the Jews opposed and hated and persecuted him the moment he announced the grand principle which animated his life,–salvation through Jesus Christ, instead of through obedience to the venerated Law of Moses.

On his return to Antioch with his beloved companion, Paul continued for a time in the peaceful ministration of apostolic duties, until it became necessary for him to go to Jerusalem to consult with the other apostles in reference to a controversy which began seriously to threaten the welfare of their common cause. This controversy was in reference to the rite of circumcision,–a rite ever held in supreme importance by the Jews. The Jewish converts to Christianity had all been previously circumcised according to the Mosaic Law, and they insisted on the circumcision of the Gentile converts also, as a mark of Christian fraternity. Paul, emancipated from Jewish prejudices and customs, regarded this rite as unessential; he believed that it was abrogated by Christ, with other technical observances of the Law, and that it was not consistent with the liberty of the Gospel to impose rites exclusively Jewish on the Pagan converts. The elders at Jerusalem, good men as they were, did not take this view; they could not bear to receive into complete Christian fellowship men who offended their prejudices in regard to matters which they regarded as sacred and obligatory as baptism itself. They would measure Christianity by their traditions; and the smaller the point of difference seemed to the enlightened Paul, the bitterer were the contests,–even as many of the schisms which subsequently divided the Church originated in questions that appear to us to be absolutely frivolous. The question very early arose, whether Christianity should be a formal and ritualistic religion,–a religion of ablutions and purifications, of distinctions between ceremonially pure and impure things,–or, rather, a religion of the spirit; whether it should be a sect or a universal religion. Paul took the latter view; declared circumcision to be useless, and freely admitted heathen converts into the Church without it, in opposition to those who virtually insisted on a Gentile becoming a Jew before he could become a Christian.

So, to settle this miserable dispute, Paul went to Jerusalem, taking with him Barnabas and Titus, who had never been circumcised,–eighteen years after the death of Jesus, when the apostles were old men, and when Peter, James, and John, having remained at Jerusalem, were the real leaders of the Jewish Church. James in particular, called the Just, was a strenuous observer of the law of circumcision,–a severe and ascetic man, and very narrow in his prejudices, but held in great veneration for his piety. Before the question was brought up in a general assembly of the brethren for discussion, Paul separately visited Peter, James, and John, and argued with them in his broad and catholic spirit, and won them over to his cause; so that through their influence it was decided that it was not essential for a Gentile to be circumcised on admission to the Church, only that he must abstain from meats offered to idols, and from eating the meat of any animal containing the blood (forbidden by Moses),–a sort of compromise, a measure by which most quarrels are finally settled; and the title of Paul as “Apostle to the Gentiles” was officially confirmed.

The controversy being settled amicably by the leaders of the infant Church, Paul and Barnabas returned to Antioch, and for a while longer continued their labors there, as the most important centre of missionary operations. But the ardent soul of Paul could not bear repose. He set about forming new plans; and the result was his second and more important missionary tour.

The relations between Paul and Barnabas had been thus far of the most intimate and affectionate kind. But now the two apostles disagreed,–Barnabas wishing to associate with them his cousin Mark, and Paul determining that the young man, however estimable, should not accompany them, because he had turned back on the former journey. It must be confessed that Paul was not very amiable and conciliatory in this matter; but his nature was earnest and stern, and he was resolved not to have a companion under his trying circumstances who had once put his hand to the plough and looked back. Neither apostle would yield, and they were obliged to separate,–reluctantly, doubtless,–Paul choosing Silas as his future companion, while Barnabas took Mark. Both were probably in the right, and both in the wrong; for the best of men have faults, and the strongest characters the most. Perhaps Paul thought that as he was now recognized as the leading apostle to the Gentiles, Barnabas should yield to him; and perhaps Barnabas felt aggrieved at the haughty dictation of one who was once his inferior in standing.

The choice of Paul, however, was admirable. Silas was a broad and liberal man, who had great influence at Jerusalem, and was entirely devoted to his superior.

“The first object of Paul was to confirm the churches he had already founded; and accordingly he began his mission by visiting the churches of Syria and Cilicia,” crossing the Taurus range by the famous Cilician Gates,–one of the most frightful mountain passes in the world,–penetrating thus into Lycaonia, and reaching Derbe, Lystra, and Iconium. At Lystra he found Timothy, whom he greatly loved, modest and timid, and made him his deacon and secretary, although he had never been circumcised. To prevent giving offence to Jewish Christians, Paul himself circumcised Timothy, in accordance with his custom of yielding to prejudices when no vital principles were involved,–which concession laid him open to the charge of inconsistency on the part of his enemies. Expediency was not disdained by Paul when the means were unobjectionable, but he did not use bad means to accomplish good ends. He always had tenderness and charity for the weaknesses of his brethren, especially intellectual weakness. What would have been intolerable to some was patiently submitted to by him, if by any means he could win even the feeble; so that he seemed to be all things to all men. No one ever exceeded him in tact.

After Paul had finished his visit to the principal cities of Galatia, he resolved to explore new lands. We next find him, after a long journey through Mysia of three hundred miles, travelling to the south of Mount Olympus, at Troas, near the ancient city of Troy. Here he fell in with Luke, a physician, who had received a careful Hellenic and Jewish education. Like Timothy, the future historian of the Acts of the Apostles was admirably fitted to be the companion of Paul. He was gentle, sympathetic, submissive, and devoted to his superior. Through Luke’s suggestion, Renan thinks, Paul determined to go to Macedonia.

So, without making a long stay at Troas, the four missionaries–Paul, Silas, Luke, and Timothy–took ship and landed at Neapolis, the seaport of Philippi on the borders of Thrace at the extreme northern shores of the Aegean Sea. They were now on European ground,–the most healthy region of the ancient world, where the people, largely of Celtic origin, were honest, earnest, and primitive in their habits. The travellers proceeded at once to Philippi, a city more Latin than Grecian, and began their work; making converts, chiefly women, among whom Lydia was the most distinguished, a wealthy woman who traded in purple. She and her whole household were baptized, and it was from her that Paul consented against his custom to accept pecuniary aid.

While the work of conversion was going on favorably, an incident occurred which hastened the departure of the missionaries. Paul exorcised a poor female slave, who brought, by her divinations and ventriloquism, great gain to her masters; and because of this destruction of the source of their income they brought suit against Paul and Silas before the magistrates, who condemned them to be beaten in the presence of the superstitious people, and then sent them to prison and put their feet fast in the stocks. The jailer and the duumvirs, however, ascertaining that the prisoners were Roman citizens and hence exempt from corporal punishment, released them, and hurried them out of the city.

Leaving Timothy and Luke at Philippi, Paul and Silas proceeded to Thessalonica, the largest and most important city of Macedonia, where there was a Jewish synagogue in which Paul preached for three consecutive Sabbaths. A few Jews were converted, but the converts were chiefly Greeks, of whom the larger part were women belonging to the best society of the city. By these converts the apostles were treated with extraordinary deference and devotion, and the church of Thessalonica soon rivalled that of Philippi in the piety and unity of its converts, becoming a model Christian church. As usual, however, the Jews stirred up animosities, and Paul and Silas were obliged to leave, spending several days at Berea and preaching successfully among the Greeks. These conquests were the most brilliant that Paul had yet made,–not among enervated Asiatics, but bright, elegant, and intelligent Europeans, where women were less degraded than in the Orient.

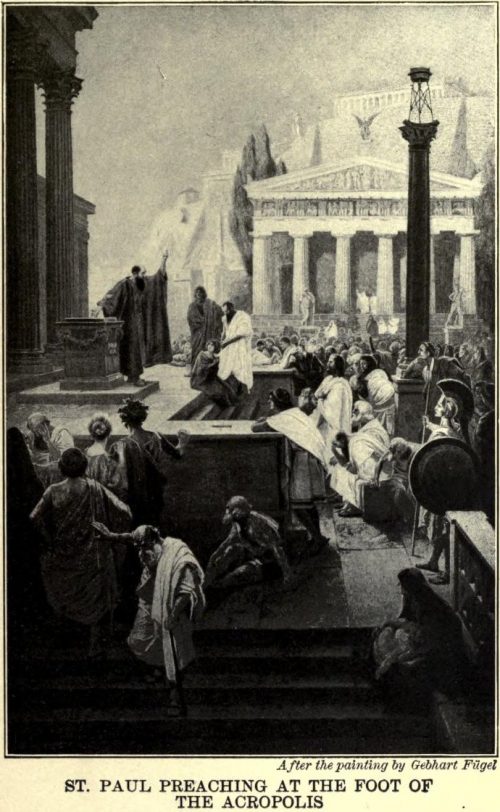

Leaving Timothy and Silas behind him, Paul, accompanied by some faithful Bereans, embarked for Athens,–the centre of philosophy and art, whose wonderful prestige had induced its Roman conquerors to preserve its ancient glories. But in the first century Athens was neither the fascinating capital of the time of Cicero, nor of the age of Chrysostom. Its temples and statues remained intact, but its schools could not then boast of a single man of genius. There remained only dilettante philosophers, rhetoricians, grammarians, pedagogues, and pedants, puffed up with conceit and arrogance, with very few real inquirers after truth, such as marked the times of Socrates and Plato. Paul, like Luther, cared nothing for art; and the thousands of statues which ornamented every part of the city seemed to him to be nothing but idols. Still, he was not mistaken in the intense paganism of the city, the absence of all earnestness of character and true religious life. He was disappointed, as afterward Augustine was when he went to Rome. He expected to find intellectual life at least, but the pretenders to superior knowledge in that degenerate university town merely traded on the achievements of their ancestors, repeating with dead lips the echo of the old philosophies. They were marked only by levity, mockery, sneers, and contemptuous arrogance; idlers were they, in quest of some new amusement.

The utter absence of sympathy among all classes given over to frivolities made Paul exceedingly lonely in Athens, and he wrote to Timothy and Silas to join him with all haste. He wandered about the streets distressed and miserable. There was no field for his labors. Who would listen to him? What ear could he reach? He was as forlorn and unheeded as a temperance lecturer would be on the boulevards of Paris. His work among the Jews was next to nothing, for where trade did not flourish there were but few Jews. Still, amid all this discouragement, it would seem that Paul attracted sufficient notice, from his conversation with the idlers and chatterers of the Agora, to be invited to address the Athenians at the Areopagus. They listened with courtesy so long as they thought he was praising their religious habits, or was making a philosophical argument against the doctrines of rival sects; but when he began to tell them of that Cross which was to them foolishness, and of that Resurrection from the dead which was alien to all their various beliefs, they were filled with scorn or relapsed into indifference. Paul’s masterly discourse on Mars Hill was an obvious failure, so far as any immediate impression was concerned. The Pagans did not persecute him,–they let him alone; they killed him with indifference. He could stand opposition, but to be laughed at as a fanatic and neglected by bright and intellectual people was more than even Paul could stand. He left Athens a lonely man, without founding a church. It was the last city in the world to receive his doctrines,–that city of grammarians, of pedants, of gymnasts, of fencing masters, of play-goers, and babblers about words. “As well might a humanitarian socialist declaim against English prejudices to the proud and exclusive fellows of Oxford and Cambridge.”

Paul, disappointed and disgusted, without waiting for Timothy, then set out for Corinth,–a much wickeder and more luxurious city than Athens, but not puffed up with intellectual pride. Here there were sailors and artisans, and slaves bearing heavy burdens, who would gladly hear the tidings of a salvation preached to the poor and miserable. Not yet was the alliance to be formed between Philosophy and Christianity. Not to the intellect was the apostolic appeal to be made, but to the conscience and the heart of those who knew and owned that they were sinners in need of forgiveness.

Paul instinctively perceived that Corinth, with its gross and shameless immoralities, was the place for him to work in. He therefore decided on a long stay, and went to live with Aquila and Priscilla, converted Jews, who followed the same trade as himself, that of tent and sail making,–a very humble calling, but one which was well patronized in that busy mart of commerce. Timothy soon joined him, with Silas. As usual, Paul preached to the Jews until they repulsed him with insults and blasphemy, when he turned to the heathen, among whom he had great success, converting the common people, including some whose names have been preserved,–Titus, Justius, Crispus, Chloe, and Phoebe. He remained in Corinth eighteen months, not without difficulties and impediments. The Jews, unable to vent their wrath upon him as fully as they wished in a city under the Roman government, appealed to the governor of the province of which Corinth was the capital. This governor is best known to us as Gallio,–a man of fine intellect, and a friend of scholars.

When Sosthenes, chief of the synagogue, led Paul before Gallio’s tribunal, accusing him of preaching a religion against the law, the proconsul interrupted him with this admirable reply: “If it were a matter of wrong, or moral outrage, it would be reasonable in me to hear you; but if it be a question of words and names and of your Law, look ye to it, for I will be no judge of such matters.” He thus summarily and contemptuously dismissed the complaint, without however taking any notice of Paul. The mistake of Gallio was that he did not comprehend that Christianity was a subject infinitely greater than a mere Jewish sect, with which, in common with educated Romans, he confounded it. In his indifference however he was not unlike other Roman governors, of whom he was one of the justest and most enlightened. In reference to the whole scene, Canon Farrar forcibly remarks that this distinguished and cultivated Gallio “flung away the greatest opportunity of his life, when he closed the lips of the haggard Jewish prisoner whom his decision had rescued from the clutches of his countrymen;” for Paul was prepared with a speech which would have been more valued, and would have been more memorable, than all the acts of Gallio’s whole government.

While Paul was pursuing his humble labors with the poor converts of Corinth, about the year 53 A.D., a memorable event took place in his career, which has had an immeasurable influence on the Christian world. Being unable personally to visit, as he desired, the churches he had founded, Paul began to write to them letters to instruct and confirm them in the faith.

The apostle’s first epistle was to his beloved brethren, in Thessalonica,–the first of that remarkable series of theological essays which in all subsequent ages have held their position as fundamentally important in the establishment of Christian doctrine. They are luminous, profound, original, remarkable alike for vigor of style and depth of spiritual significance. They are not moral essays like those of Confucius, nor mystic and obscure speculations like those of Buddha, but grand treatises on revealed truth, written, as it were, with his heart’s blood, and vivid as fire in a dark night. In these epistles we see also Paul’s intense personality, his frank egotism, his devotion to his work, his sincerity and earnestness, his affectionate nature, his tolerant and catholic spirit, and also his power of sarcasm, his warm passions, and his unbending will. He enjoins the necessity of faith, which is a gift, with the practice of virtues that appeal to consciousness and emanate from love and purity of heart. These letters are exhortations to a lofty life and childlike acceptance of revealed truths. The apostle warns his little flock against the evils that surrounded them, and which so easily beset them,–especially unchastity and drunkenness, and strifes, bickerings, slanders, and retaliations. He exhorts them to unceasing prayer, the feeling of constant dependence, and hence the supreme need of divine grace to keep them from falling, and to enable them to grow in spiritual strength. He promises as the fruit of spiritual victories immeasurable joys, not only amid present evils, but in the glorious future when the mortal shall put on immortality. Especially and repeatedly does he urge them to “have also that mind which was in Christ Jesus,” showing itself in humility, willingness to serve others, unselfish consideration of others, even the preference of others’ interests before their own,–a combination of the homely practical with the divinely ideal, such as the world had never learned from any earlier philosophy of life.

Paul at last felt that he must revisit the earlier churches, especially those of Syria. It was three years since he had left Antioch. But more than all, he wished to consult with his brethren in Jerusalem, and to be present at the feast of the Passover. Bidding an affectionate adieu to his Christian friends, he set out for the little seaport of Cenchrea, accompanied by Aquila and his wife Priscilla, and then set sail for Ephesus, on his way to Jerusalem. In his haste to reach the end of his journey he did not tarry at Ephesus, but took another vessel, and arrived at Caesarea without any recorded accident. Nor did he make a long visit at Jerusalem, probably to avoid a rupture with James, the head of the church in that city, whose views about Jewish ceremonials, as already noted, differed from his.

Paul returned again to Ephesus, where he made a sojourn of three years, following his trade for a living, while he founded a church in that city of necromancers, sorcerers, magicians, courtesans, mimics, flute-players,–a city abandoned to Asiatic sensualities and superstitious rites; an exceedingly wicked and luxurious city, yet famous for arts, especially for the grandest temple ever erected by the Greeks, one of the seven wonders of the world. It was in the most abandoned capitals, with mixed populations, that the greatest triumphs of Christianity were achieved. Antioch, Corinth, and Ephesus were more favorable to the establishment of Christian churches than Jerusalem and Athens.

But the trials of Paul in Ephesus, the capital of Asia Minor, the most celebrated of all the Ionian cities,–“more Hellenic than Antioch, more Oriental than Corinth, more wealthy than Thessalonica, more populous than Athens,”–were incessant and discouraging, since it was the headquarters of pagan superstitions, and of all forms of magical imposture. As usual, he was reviled and slandered by the Jews; but he was also at this time an object of intense hatred to the priests and image-makers of the Temple of Diana, troubled in mind by evil reports concerning the converts he had made in other cities, physically weak and depressed by repeated attacks of sickness, oppressed by cares and labors, exposed to constant dangers, his life an incessant mortification and suffering, “killed all the day long,” carrying about him wherever he went “the deadness of the crucified Christ.”

Paul’s labors in Ephesus were nevertheless successful. He made many converts and exercised an extraordinary influence,–among other things causing magicians voluntarily to burn their own costly books, as Savonarola afterward made a bonfire of vanities at Florence. His sojourn was cut short at length by the riot which was made by the various persons who were directly or indirectly supported by the revenues of the Temple,–a mongrel mob, brought to terms by the tact of the town clerk, who reminded the howling dervishes and angry silversmiths of the punishment which might be inflicted on them by the Roman proconsul for raising a disturbance and breaking the law.

Yet Paul with difficulty escaped from Ephesus and departed again for Greece, not however until he had written his extraordinary Epistles to the Corinthians, who had sadly departed from his teachings both in morals and doctrine, either through ignorance, or in consequence of the depravity which they had but imperfectly conquered. The infant churches were deplorably split into factions, “the result of the visits from various teachers who succeeded Paul, and who built on his foundations very dubious materials by way of superstructure,”–even Apollos himself, an Alexandrian Jew baptized by the Apostle John, the most eloquent and attractive preacher of the day, who turned everybody’s head. In the churches women rose to give their opinions without being veiled, as if they were Greek courtesans; the Agapae, or love-feasts, had degenerated into luxurious banquets; and unchastity, the peculiar vice of the Corinthians, went unrebuked. These evils Paul rebukes, and lays down rules for the faithful in reference to marriage, to the position of women, to the observance of the Lord’s Supper, and sundry other things, enjoining forbearance and love. His chapter in reference to charity is justly regarded by all writers and commentators as the nearest approach in Christian literature to the Sermon on the Mount. Scarcely less remarkable is the chapter on death and the resurrection, shedding more light on that great subject than all other writers combined in heathen and Christian annals,–one of the profoundest treatises ever written by mortal man, and which can be explained only as the result of a supernatural revelation.

Paul’s second sojourn in Macedonia lasted only six months; this time he spent in going from city to city confirming the infant churches, remaining longest in Thessalonica and Philippi, where his most faithful converts were found. Here Titus joined him, bringing good news from Corinth. Still, there were dissensions and evils in that troublesome church which called for a second letter. In this letter he sets forth, not in the spirit of egotism, the various sufferings and perils he had endured, few of which are alluded to by Luke: “Of the Jews five times received I forty stripes save one; thrice was I beaten with rods; once was I stoned; thrice I suffered shipwreck; a night and a day have I spent in the deep; in journeyings often; in perils of rivers, in perils of robbers, in perils from my own race, in perils from the Gentiles, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness, in perils in the sea, in perils among false brethren; in toil and weariness, in sleeplessness often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often; besides anxiety for all the churches.”

It was probably at the close of the year 57 A.D. that Paul set out for Corinth, with Titus, Timothy, Sosthenes, and other companions. During the three months he remained in that city he probably wrote his Epistle to the Galatians and his Epistle to the Romans,–the latter the most profound of all his writings, setting forth the sum and substance of his theology, in which the great doctrine of justification by faith is severely elaborated. The whole epistle is a war on pagan philosophy, the insufficiency of good works without faith,–the lever by which in later times Wyclif, Huss, Luther, Calvin, Knox, and Saint Cyran overthrew a pharisaic system of outward righteousness. In the Epistle to the Galatians Paul speaks with unusual boldness and earnestness, severely rebuking them for their departure from the truth, and reiterating with dogmatic ardor the inutility of circumcision as of the Law abrogated by Christ, with whom, in the liberty which he proclaimed, there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither bond nor free, neither male nor female, but all are one in Him. And Paul reminds them,–a bitter pill to the Jews,–that this is taught in the promise made to Abraham four hundred and fifty years before the Law was declared by Moses, by which promise all races and tribes and people are to be blessed to remotest generations. This epistle not only breathes the largest Christian liberty,–the equality of all men before God,–but it asserts, as in the Epistle to the Romans, with terrible distinctness, that salvation is by faith in Christ and not by deeds of the Law, which is only a schoolmaster to prepare the way for the ascendency of Jesus.

I need not dwell on these two great epistles, which embody the substance of the Pauline theology received by the Church for eighteen hundred years, and which can never be abrogated so long as Paul is regarded as an authority in Christian doctrine.

I return to a brief notice of Paul’s last visit to Jerusalem, which was made against the expostulations of his friends and disciples in Ephesus, who gathered around him weeping, knowing well that they never would see his face again. But he was inflexible in his resolution, declaring that he had no fear of chains, and was ready to die at Jerusalem for the name of Jesus. Why he should have persisted in his resolution, so full of danger; why he should again have thrown himself into the hands of his bitterest enemies, thirsty for his blood,–we do not know, for he had no new truth to declare. But the brethren were forced to yield to his strong will, and all they could do was to provide him with a sufficient escort to shield him from ordinary dangers on the way.

The long voyage from Ephesus was prosperous but tedious, and on the last day before the Pentecostal feast, in May, in the year 58 A.D., Paul for the fifth time entered Jerusalem. His meeting with the elders, under the presidency of James,–“the stern, white-robed, ascetic, mysterious prophet,”–was cold. His personal friends in Jerusalem were few, and his enemies were numerous, powerful, and bitter; for he had not only emancipated himself from the Jewish Law, with all its rites and ceremonies, but had made it of no account in all the churches he had founded. What had he naturally to expect from the zealots for that Law but a renewed persecution? Even the Jewish Christians gave no thanks for the splendid contribution which Paul had gathered in Asia for the relief of their poor. Nor was there any exultation among them when Paul narrated his successful labors among the Gentiles. They pretended to rejoice, but added, “You observe, brother, how many myriads of the Jews there are that have embraced the faith, and they are all zealots for the Law. And we are informed that thou teachest all the Jews that are among the Gentiles to forsake Moses.” There was no cordiality among the Jewish elders of the Christian community, and deadly hostility among the unconverted Jews, for they had doubtless heard of Paul’s marvellous career.

Jerusalem was then full of strangers, and the Jews of Asia recognizing Paul in the Temple, raised a disturbance, pretending that he was a profaner of the sacred edifice. The crowd of fanatics seized him, dragged him out of the Temple, and set about to kill him. But the Roman authorities interfered, and rescuing him from the hands of the infuriated mob, bore him to the castle, the tower of Antonia. When they arrived at the stairs of the tower, Paul begged the tribune to be allowed to speak to the angry and demented crowd. The request was granted, and he made a speech in Hebrew, narrating his early history and conversion; but when he came to his mission to the Gentiles, the uproar was renewed, the people shouting, “Away with such a fellow from the earth, for it is not fit that he should live!” And Paul would have been bound and scourged, had he not proclaimed that he was a Roman citizen.

On the next day the Roman magistrate summoned the chief priests and the Sanhedrim, to give Paul an opportunity to make his defence in the matter of which he was accused. Ananias the high-priest presided, and the Roman tribune was present at the proceedings, which were tumultuous and angry. Paul seeing that the assembly was made up of Pharisees, Sadducees, and hostile parties, made no elaborate defence, and the tribune dissolved the assembly; but forty of the most hostile and fanatical formed a conspiracy, and took a solemn oath not to eat or drink until they had assassinated him. The plot reached the ears of a nephew of Paul, who revealed it to the tribune. The officer listened attentively to all the details, and at once took his resolution to send Paul to Caesarea, both to get him out of the hands of the Jews, and to have him judged by the procurator Felix. Accordingly, accompanied by an escort of two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, and two hundred spearmen of the guard, Paul was sent by night, secretly, to the Roman capital of the Province. He entered the city in the course of the next day, and was at once led to the presence of the governor.

Felix, as procurator, ruled over Judaea with the power of a king. He had been a freedman of the Emperor Claudius, and was allied by marriage to Claudius himself,–an ambitious, extortionate, and infamous governor. Felix was obliged to give Paul a fair trial, and after five days the indomitable missionary was confronted with accusers, among whom appeared the high-priest Ananias. They associated with them a lawyer called Tertullus, of oratorical gifts, who conducted the case. The principal charges made against Paul were that he was a public pest and leader of seditions; that he was a ringleader of the Nazarenes (the contemptuous name which the Jews gave to the Christians); and that he had attempted to profane the Temple, which was a capital offence according to the Jewish law. Paul easily refuted these charges, and had Felix been an upright judge he would have dismissed the case; but supposing the apostle to be rich because of the handsome contributions he had brought from Asia Minor for the poor converts at Jerusalem, Felix retained Paul in the hope of a bribe. A few days after, Drusilla, a young woman of great beauty and accomplishments, who had eloped from her husband to be married to Felix, was desirous to hear so famous a man as Paul explain his faith; and Felix, to gratify her curiosity, summoned his distinguished prisoner to discourse before them. Paul eagerly embraced the opportunity; but instead of explaining the Christian mysteries, he reasoned about righteousness, self-control, and retribution,–moral truths which even intelligent heathen accepted, and as to which the consciences of both, his hearers must have tingled; indeed, he discoursed with such matchless boldness and power that Felix trembled with fear as he remembered the arts by which he had risen from the condition of a slave, and the extortions and cruelties by which he had become enriched, to say nothing of the lusts and abominations which had disgraced his career. However, he did not set Paul free, but kept him a prisoner for two years, in order to gain favor with the Jews, or to receive a bribe.

Porcius Festus, the successor of Felix, was a just and inflexible man, who arrived at Caesarea in the year 60 A.D., when Paul was fifty-eight years of age. Immediately the enemies of Paul, especially the Sadducees, renewed their demands to have him again tried; and Festus, wishing to be just, ordered the second trial. Again Paul defended himself with masterly ability, proving that he had done nothing against the Jewish law or Temple, or against the Roman Emperor. Festus, probably not seeing the aim of the conspirators, was disposed to send Paul back to Jerusalem to be tried by a Jewish court. To prevent this, as at Jerusalem condemnation and death would be certain, Paul, remembering that he was a Roman citizen, fell back on his privilege, and at once appealed to Caesar himself. The governor, at first surprised by such an unexpected demand, consulted with his assistants for a moment, and then replied: “Thou hast appealed unto Caesar, and unto Caesar shalt thou go.” Thus ended the trial of Paul; and thus providentially was the way open to him, without expense to himself, to go to Rome, which of all cities he wished to visit, and where he hoped to continue, even under bonds and restrictions, his missionary labors.

In the meantime, before a ship could be got in readiness to transport him and other prisoners to Rome, Herod Agrippa II., with his sister Bernice, came to Caesarea to pay a visit to the new governor. Conversation naturally turned upon the late extraordinary trial, and Agrippa expressed a desire to hear the prisoner speak, for he had heard much about him. Festus willingly acceded to this wish, and the next day Paul was again summoned before the king and the procurator. Agrippa and Bernice appeared in great pomp with their attendants; all the officers of the army and the principal men of the city were also present. It was the most splendid audience that Paul had ever addressed. He was equal to the occasion, and delivered a discourse on his familiar topics,–his own miraculous conversion and his mission to the Gentiles to preach the crucified and risen Christ,–things new to Festus, who thought that Paul was visionary, and had lost his balance from excess of learning. Agrippa, however, familiar with Jewish law and the prophecies concerning the Messiah, was much impressed with Paul’s eloquence, and exclaimed: “Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian!” When the assembly broke up, Agrippa said, “This man might have been set at liberty, if he had not appealed unto Caesar.” Paul, however, did not wish to be set at liberty among bitter and howling enemies; he preferred to go to Rome, and would not withdraw his appeal. So in due time he embarked for Italy under the charge of a centurion, accompanied with other prisoners and his friends Timothy, Luke, and Aristarchus of Thessalonica.

The voyage from Caesarea to Italy was a long one, and in the autumn was a dangerous one, as in Paul’s case it unfortunately proved.

The following spring, however, after shipwreck and divers perils and manifold fatigues, Paul arrived at Rome, in the year 61 A.D., in the seventh year of the Emperor Nero. Here the centurion handed Paul over to the prefect of the praetorian guards, by whom he was subjected to a merely nominal custody, although, according to Roman custom, he was chained to a soldier. But he was treated with great lenity, was allowed to have lodgings, to receive his friends freely, and to hold Christian meetings in his own house; and no one molested him. For two years Paul remained at Rome, a fettered prisoner it is true, but cheered by friendly visits, and attended by Luke, his “beloved physician” and biographer, by Timothy and other devoted disciples. During this second imprisonment Paul could see very little outside the praetorian barracks, but his friends brought him the news, and he had ample time to write letters. He had no intercourse with gifted and fortunate Romans; his acquaintance was probably confined to the praetorian soldiers, and some of the humbler classes who sought Christian instruction. But from this period we date many of his epistles, on which his fame and influence largely rest as a theologian and man of genius. Among those which he wrote from Rome were the Epistles to the Colossians, the Ephesians, and many pastoral letters like those written to Philemon, Titus, and Timothy. We know but little of the life of Paul after his arrival at Rome, for at this point Saint Luke closes his narrative, and all after this is conjecture and tradition.[4] But the main part of Paul’s work was accomplished when he was first sent to Rome as a prisoner to be tried in the imperial courts; and there is but little doubt that he finally met the death he so heroically contemplated, at the hands of the monster Nero, who martyred such a vast multitude of Paul’s fellow-Christians.

[4] There has been much doubt as to whether Paul was martyred during the three years of this imprisonment, or whether he was acquitted, left Rome, visited his beloved churches in Macedonia and Asia Minor, went to preach the gospel in Spain, and was again arrested, taken to Rome, and there beheaded. The earliest authorities seem to have been agreed upon the second hypothesis; and this is based chiefly upon a statement made by Paul’s disciple Clement to the effect that the apostle had preached in “the extremity of the West” (an expression of Roman writers to denote Spain), and also on the impossibility of placing certain facts mentioned in the second letter to Timothy and the one to Titus in the period of the first imprisonment. He was certainly tried, defended himself, and he may have been at first acquitted.

At Jerusalem and at Antioch he had vindicated the freedom of the Gentile from the yoke of the Levitical Law; in his letters to the Romans and Galatians he had proclaimed both to Jew and Gentile that they were not under the law, but under grace. During the space of twenty years Paul had preached the gospel of Jesus as the Christ in the chief cities of the world, and had formulated the truths of Christianity. What marvellous labors! But it does not appear that this apostle’s extraordinary work was fully appreciated in his day, certainly not by the Jewish Christians at Jerusalem; nor does it appear even that his pre-eminence among the apostles was conceded until the third and fourth centuries. He himself was often sad and discouraged in not seeing a larger success, yet recognized himself as a layer of foundations. Like our modern missionaries, Paul simply sowed the seed; the fruit was not to be gathered in until centuries after his death. Before he died, as is seen in his second letter to Timothy, many of his friends and disciples deserted him, and he was left almost alone. He had to defend himself single-handed against the capricious tyrant who ruled the world, and who wished to cast on the Christians the stain of his greatest crime, the conflagration of his capital. As we have said, all details pertaining to the life of Paul after his arrival at Rome are simply conjectural, and although interesting, they cannot give us the satisfaction of certainty.

But in closing, after enumerating the labors and writings of this great apostle, it is not inopportune to say a few words about his remarkable character, although I have now and again alluded to his personal traits in the course of this narrative.

Paul is the most prominent figure of all the great men who have adorned, or advanced the interest of, the Christian Church. Great pulpit orators, renowned theologians, profound philosophers, immortal poets, successful reformers, and enlightened monarchs have never disputed his intellectual ascendency; to all alike he has been a model and a marvel. The grand old missionary stands out in history as a matchless example of Christian living, a sure guide in Christian doctrine. No more favored mortal is ever likely to appear; he is the counterpart of Moses as a divine teacher to all generations. The popes may exalt Saint Peter as the founder of their spiritual empire, but when their empire as an institution shall crumble away, as all institutions must which are not founded on the “Rock” which it was the mission of apostles to proclaim, Paul will stand out the most illustrious of all Christian teachers.

As a man Paul had his faults, but his virtues were transcendent; and these virtues he himself traced to divine grace, enabling him to conquer his infirmities and prejudices, and to perform astonishing labors, and to endure no less marvellous sufferings. His humanity was never lost in his discouraging warfare; he sympathized with human sorrows and afflictions; he was tolerant, after his conversion, of human infirmities, while enjoining a severe morality. He was a man of native genius, with profound insight into spiritual truth. Trained in philosophy and disputation, his gentleness and tact in dealing with those who opposed him are a lesson to all controversialists. His voluntary sufferings have endeared him to the heart of the world, since they were consecrated to the welfare of the world he sought to enlighten. As an encouragement to others, he enumerates the calamities which happened to him from his zeal to serve mankind, but he never complains of them or regards them as a mystery, or as anything but the natural result of unappreciated devotion. He was more cheerful than Confucius, who felt that his life had been a failure; more serene than Plato when surrounded by admiring followers. He regarded every Christian man as a brother and a friend. He associated freely with women, without even calling out a sneer or a reproach. He taught principles of self-control rather than rules of specific asceticism, and hence recommended wine to Timothy and encouraged friendship between men and women, when intemperance and unchastity were the scandal and disgrace of the age; although so far as himself was concerned, he would not eat meat, if thereby he should give offence to the weakest of his weak-minded brethren. He enjoined filial piety, obedience to rulers, and kindness to servants as among the highest duties of life. He was frugal, but independent and hospitable; he had but few wants, and submitted patiently to every inconvenience. He was the impersonation of gentleness, sympathy, and love, although a man of iron will and indomitable resolution. He claimed nothing but the right to speak his honest opinions, and the privilege to be judged according to the laws. He magnified his office, but only the more easily to win men to his noble cause. To this great cause he was devoted heart and soul, without ever losing courage, or turning back for a moment in despondency or fear. He was as courageous as he was faithful; as indifferent to reproach as he was eager for friendship. As a martyr he was peerless, since his life was a protracted martyrdom. He was a hero, always gallantly fighting for the truth whatever may have been the array and howling of his foes; and when wounded and battered by his enemies he returned to the fight for his principles with all the earnestness, but without the wrath, of a knight of chivalry. He never indulged in angry recriminations or used unseemly epithets, but was unsparing in his denunciation of sin,–as seen in his memorable description of the vices of the Romans. Self-sacrifice was the law of his life. His faith was unshaken in every crisis and in every danger. It was this which especially fitted him, as well as his ceaseless energies and superb intellect, to be a leader of mankind. To Paul, and to Paul more than to any other apostle, was given the exalted privilege of being the recognized interpreter of Christian doctrine for both philosophers and the people, for all coming ages; and at the close of his career, worn out with labor and suffering, yet conscious of the services which he had rendered and of the victories he had won, and possibly in view of approaching martyrdom, he was enabled triumphantly to say: “I have fought a good fight; I have finished my course; I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, shall give me at that day.”

Beacon Lights of History, Volume II : Jewish Heroes and Prophets