William of Wykeham : Gothic Architecture – Beacon Lights of History, Volume V : The Middle Ages by John Lord

Beacon Lights of History, Volume V : The Middle Ages

Mohammed : Saracenic Conquests

Charlemagne : Revival of Western Empire

Hildebrand : The Papal Empire

Saint Bernard : Monastic Institutions

Saint Anselm : Mediaeval Theology

Thomas Aquinas : The Scholastic Philosophy

Thomas Becket : Prelatical Power

The Feudal System

The Crusades

William of Wykeham : Gothic Architecture

John Wyclif : Dawn of the Reformation

Beacon Lights of History, Volume V : The Middle Ages

by

John Lord

Topics Covered

Roman architecture First form of a Christian church

The change to the Romanesque

Its peculiarities

Its connection with Monasticism

Gloomy aspect of the churches of the tenth and eleventh centuries

Effect of the Crusades on church architecture

Church architecture becomes cheerful

The Gothic churches of France and Germany

The English Mediaeval churches

Glories of the pointed arch

Effect of the Renaissance on architecture

Mongrel style of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

Revival of the pure gothic

Churches should be adapted to their uses

Incongruity of Protestantism with ritualistic architecture

Protestantism demands a church for preaching

Gothic vaults unfavorable to oratory

William of Wykeham : Gothic Architecture

William of Wykeham A.D. 1324-1404.

A.D. 1100-1400.

Church Architecture is the only addition which the Middle Ages made to Art; but even this fact is remarkable when we consider the barbarism and ignorance of the Teutonic nations in those dark and gloomy times. It is difficult to conceive how it could have arisen, except from the stimulus of religious ideas and sentiments,–like the vast temples of the Egyptians. The artists who built the hoary and attractive cathedrals and abbey churches which we so much admire are unknown men to us, and yet they were great benefactors. It is probable that they were practical and working architects, like those who built the temples of Greece, who quietly sought to accomplish their ends,–not to make pictures, but to make buildings,–as economically as they could consistently with the end proposed, which end they always had in view.

In this Lecture I shall not go back to classic antiquity, nor shall I undertake to enter upon any disquisition on Art itself, but simply present the historical developments of the Church architecture of the Middle Ages. It is a technical and complicated subject, but I shall try to make myself understood. It suggests, however, great ideas and national developments, and ought to be interesting.

The Romans added nothing to the architecture of the Greeks except the arch, and the use of brick and small stones for the materials of their stupendous structures. Now Christianity and the Middle Ages seized the arch and the materials of the Roman architects, and gradually formed from these a new style of architecture. In Roman architecture there was no symbolism, no poetry, nothing to represent consecrated sentiments. It was mundane in its ideas and ends; everything was for utility. The grandest efforts of the Romans were feats of engineering skill, rather than creations inspired by the love of the beautiful. What was beautiful in their edifices was borrowed from the Greeks; what was original was intended to accommodate great multitudes, whether they sought the sports of the amphitheatre or the luxury of the bath. Their temples were small, comparatively, and were Grecian.

The first stage in the development of Church architecture was reached amid the declining glories of Roman civilization, before the fall of the Empire; but the first model of a Christian church was not built until after the imperial persecutions. The early Christians worshipped God in upper chambers, in catacombs, in retired places, where they would not be molested, where they could hide in safety. Their assemblies were small, and their meetings unimportant. They did nothing to attract attention. The worshippers were mostly simple-minded, unlettered, plebeian people, with now and then a converted philosopher, or centurion, or lady of rank They met for prayer, exhortation, the reading of the Scriptures, the singing of sacred melodies, and mutual support in trying times. They did not want grand edifices. The plainer the place in which they assembled the better suited it was to their circumstances and necessities. They scarcely needed a rostrum, for the age of sermons had not begun; still less the age of litanies and music and pomps. For such people, in that palmy age of faith and courage, when the seeds of a new religion were planted in danger and watered with tears; when their minds were directed almost entirely to the soul’s welfare and future glory; when they loved one another with true Christian disinterestedness; when they stimulated each other’s enthusiasm by devotion to a common cause (one Lord, one faith, one baptism); when they were too insignificant to take any social rank, too poor to be of any political account, too ignorant to attract the attention of philosophers,–any place where they would be unmolested and retired was enough. In process of time, when their numbers had increased, and when and wherever they were tolerated; when money began to flow into the treasuries; and especially when some gifted leader (educated perhaps in famous schools, yet who was fervent and eloquent) desired a wider field for usefulness,–then church edifices became necessary.

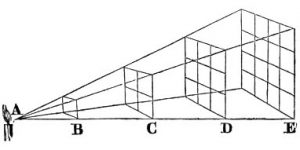

This original church was modelled after the ancient Basilica, or hall of justice or of commerce: at one end was an elevated tribunal, and back of this what was called the “apsis,”–a rounded space with arched roof. The whole was railed off or separated from the auditory, and was reserved for the clergy, who in the fourth century had become a class. The apsis had no window, was vaulted, and its walls were covered with figures of Christ and of the saints, or of eminent Christians who in later times were canonized by the popes. Between the apsis and the auditory, called the “nave,” was the altar; for by this time the Church was borrowing names and emblems from the Jews and the old religions. From the apsis to the extremity of the other end of the building were two rows of pillars supporting an upper wall, broken by circular arches and windows, called now the “clear story.” In the low walls of the side aisles were also windows. Both the nave and the aisles supported a framework of roof, lined with a ceiling adorned with painting.

For some time we see no marked departure, at this stage, from the ancient basilica. The church is simple, not much adorned, and adapted to preaching. The age in which it was built was the age of pulpit orators, when bishops preached,–like Basil, Chrysostom, Ambrose, Augustine, and Leo,–when preaching was an important part of the service, by the foolishness of which the world was to be converted. Probably there were but few what we should call fine churches, but there was one at Rome which was justly celebrated, built by Theodosius, and called St. Paul’s. It is now outside the walls of the modern city. The nave is divided into five aisles, and the main one, opening into the apsis, is spanned by a lofty arch supported by two colossal columns. The apsis is eighty feet in breadth. All parts of the church–one of the largest of Rome–are decorated with mosaics. It has two small transepts at the extremity of the nave, on each side of the apsis. The four rows of magnificent columns, supporting semicircular arches, are Corinthian. In this church the Greek and Roman architecture predominates. The essential form of the church is like a Pagan basilica. We see convenience, but neither splendor nor poetry. Moreover it is cheerful. It has an altar and an apsis, but it is adapted to preaching rather than to singing. The public dangers produce oratory, not chants. The voice of the preacher penetrates the minds of the people, as did that of Savonarola at Florence announcing the invasion of Italy by the French,–days of fear and anxiety, reminding us also of Chrysostom at Antioch, when in his spacious basilican church he roused the people to penitence, to avert the ire of Theodosius.

The first transition from the basilica to the Gothic church is called the Romanesque, and was made after the fall of the Empire, when the barbarians had erected new kingdoms on its ruins; when literature and art were indeed crushed, yet when universal desolation was succeeded by new forms of government and new habits of life; when the clergy had become an enormous power, greatly enriched by the contributions of Christian princes. This transition retained the traditions of the fallen Empire, and yet was adapted to a semi-civilized people, nominally converted to Christianity. It arose after the fall of the Merovingians, when Charlemagne was seeking to restore the glory of the Western Empire. Paganism had been suppressed by law; even heresies were extinguished in the West. Kings and people were alike orthodox, and bowed to the domination of the Church. Abbeys and convents were founded everywhere and richly endowed. The different States and kingdoms were poor, but the wealth that existed was deposited in sacred retreats. The powers of the State were the nobles, warlike and ignorant, rapidly becoming feudal barons, acknowledging only a nominal fealty to the Crown. Kings had no glory, defied by their own subjects and unsupported by standing armies. But these haughty barons were met face to face by equally haughty bishops, armed with spiritual weapons. These bishops were surrounded and supported by priests, secular and regular,–by those who ruled the people in small parishes, and those who ruled the upper classes in their monastic cells. Learning had fled to monasteries (what little there was), and the Church became a new attraction.

The architects of the Romanesque, who were probably churchmen, retained the nave of the basilica, but made it narrower, and used but two rows of columns. They introduced the transepts, or cross-enclosures, making them to project north and south of the nave, in the space separated from the apsis; and the apsis was expanded into the choir, filled with priests and choristers. The building now assumes the form of a cross. The choir is elevated several steps above the nave, and beneath it is the crypt, where the bishops and abbots and saints are buried. At the intersection of choir, nave, and transept,–an open, square place,–rises a square tower, at each corner of which is a massive pier supporting four arches. The windows are narrow, with semicircular arches. At the western entrance, at the end opposite the apse, is a small porch, where the consecrated water is placed, in an urn or basin, and this is inclosed between two towers. The old Roman atrium, or fore-court, entirely disappears. In its place is a grander façade; and the pillars–which are all internal, like those of an Egyptian temple, not external, as in the Greek temple–have no longer Grecian capitals, but new combinations of every variety, and the pillars are even more heavy and massive than the Doric. The flat wooden ceiling of the nave disappears, on account of frequent fires, and the eye rests on arches supporting a stone roof. All the arches are semicircular, like those of the Coliseum and of the Roman aqueducts and baths. They are built of small stones united by cement. The building is low and heavy, and its external beauty is in the west front or façade, with its square towers and circular window and ornamented portal. The internal beauty is from the pillars supporting the roof, and the tower which intersects the nave, choir, and transepts. Sometimes, instead of a tower there is a dome, reminding us of Byzantine workmanship.

But this Romanesque church is also connected with monastic institutions, whose extensive buildings join the church at the north or south. The church is wedded to monasticism; one supports the other, and both make a unity exceedingly efficient in the Middle Ages. The communication between the church and the convent is effected by a cloister,–a vaulted gallery surrounding a square, open space, where the brothers walk and meditate, but do not talk, except in undertone or whisper; for all the precincts are sacred, made for contemplation and silence,–a retreat from the noisy, barbaric world. Connected with the cloisters is a court opening into the refectory, where the brothers dine on herbs and eggs and a little meat,–also in silence, and, where the rule is strict, in gloom,–an ascetic, dreary discipline. The whole range of buildings is enclosed with walls, like a fortress. You see in this architecture the gloom and desolation which overspread the world. Churches are heavy and sombre; they are places for dreary meditation on the end of the world, on the failure of civilization, on the degradation of humanity,–and yet the only places where man may be brought in contact with the Deity who presides over a fallen world, exalting human hopes to heaven, where miseries end, and worship begins.

This style of architecture prevailed till the twelfth century, and was seen in its greatest perfection in Germany under the Saxon emperors, especially in the Rhenish provinces, as in the cathedrals of Spires, Mentz, Worms, and Nuremberg. Its general effect was gloomy and heavy; a separation from the outward world,–a world disgraced by feudal wars and peasants’ wrongs and general ignorance, which made men sad, morose, inhuman. It flourished in ages when the poor had no redress, and were trodden under the feet of hard feudal masters; when there was no law but of brute force; when luxuries were few and comforts rare,–an age of hardship, privation, poverty, suffering; an age of isolations and sorrows, when men were forced to look beyond the grave for peace and hope, when immortality through a Redeemer was the highest inspiration of life. Everybody was agitated by fears. The clergy made use of this universal feeling by presenting the terrors of the law,–the penalty of sin,–everlasting physical burnings, from which the tortured soul could be extricated only by penance and self-expiation, offerings to the Church, and entire subserviency to the will of the priest, who held the keys of heaven and hell. The men who lived when the Romanesque churches dotted every part in Europe looked upon society and saw nothing but grief,–heavy burdens, injustices, oppressions, cruel wrongs; and they hid their faces and wept, and said: “Let us retreat from this miserable world which discord ravages; let us hide ourselves in contemplation; let us prepare to meet God in judgment; let us bring to Him our offering; let us propitiate Him; let us build Him a house, where we may chant our mournful songs.” So the church arises,–in Germany, in France, in England,–solemn, mystical, massive, a type of sorrow, in the form of a cross, with “a sepulchral crypt like the man in the tomb, before the lofty spire pointed to the man who had risen to Heaven.” The church is still struggling, and is not jubilant, except in Gregorian chants, and is not therefore lofty or ornamental. It is a vault. It is more like a catacomb than a basilica, for the world is buried deep in sorrows and fears. Look to any of the Saxon churches of the period when the Romanesque prevailed, and they are low, gloomy, and damp, though massive and solemn. The church as an edifice ever represents the Church as an institution or a power, ever typifies prevailing sentiments and ideas. Perhaps the finest of the old Romanesque churches was that of Cluny, in Burgundy, destroyed during the French Revolution. It had five aisles, and was five hundred and twenty feet in length. It had a stately tower at the intersection of the transepts, and six other towers. It was early Norman, and loftier than the Saxon churches, although heavy and massive like them.

But the Romanesque church, with all its varieties, is still gloomy, dark, sepulchral, reminding us of the sorrows of the Middle Ages, and the dreary character of prevailing religious sentiments,–fervent, sincere, profound, but sad,–the sentiments of an age of ignorance and faith.

The Crusades came. A new era burst upon the world. The old ideas became modified; society became more cheerful, because more chivalric, adventurous, poetic. The world opened towards the East, and was larger than was before supposed. Liberality of mind began to dawn on the darkened ages; no longer were priests supreme. The gay Provençals began to sing; the universities began to teach and to question. The Scholastic philosophy sent forth such daring thinkers as Erigena and Abélard. Orthodoxy was still supreme before such mighty intellects as Anselm, Bernard, and Thomas Aquinas, but it was assailed. Abélard put forth his puzzling questions. The Schoolmen began to think for themselves, and the iron weight of Feudalism was less oppressive. Free cities and commerce began to enrich the people. Kings were becoming more powerful; grim spiritual despotism was less arrogant. The end of the world, it was found, had not come. A glorious future began to shed forth the beams of its coming day. It was the dawn of a new civilization.

So a lighter, more cheerful, and grander architecture, with symbolic beauties, appeared with changing ideas and sentiments. The Church, no longer a gloomy power, struggling with Saracens and barbarism, but dominant, triumphant, issues forth from darksome crypts and soars upward,–elevates her vaulted roofs. “The Oriental ogive appears…. The architects heap arcade on arcade, ogive on ogive, pyramid on pyramid, and give to all geometrical symmetry and artistic grace…. The Greek column is there, but dilated to colossal proportions, and exfoliated in a variegated capital.” The old Roman arch disappears, and the pointed arch is substituted,–graceful and elevated. The old Egyptian obelisk appears in the spire reaching to heaven, full of aspiration. The window becomes larger and encroaches on the naked wall, and radiates in mystic roses. The arches widen and the piers become more lofty. Stained glass appears and diffuses religious light. Every part of the church becomes decorated and symbolical and harmonious, though infinitely variegated. The altars have pictures over them. Shrines and monuments appear in the niches. The dresses of the priests are more gorgeous. The music of the choir peals forth hallelujahs. Christ is risen from the tomb. “The purple of his blood colors the windows.” The roof, like pinnacles and spires, seems to reach the skies. The pressure of the walls is downwards rather than lateral. The vertical lines of Cologne are as marked as the old horizontal lines of the Parthenon. The walls too are not so heavy, and are supported by buttresses, which give increased beauty to the exterior,–greater light and shade. “Every part of the church seems to press forward and strive for greater freedom, for outward manifestation.” Even the broad and expansive window presses to the outer surface of the walls, now broken by buttresses and pinnacles. The window–the eye of the edifice–is more cheerful and intelligent. More calm is the imposing façade, with its mighty towers and lofty spires, tapering like a pyramid, with its round oriel window rich in beautiful tracery, and its wide portal with sculptured saints and martyrs. And in all the churches you see geometrical proportions. “Even the cross of the church is deduced from the figure by which Euclid constructed the equilateral triangle,” The columns present the proportions of the Doric, as to diameter and height. The love of the true and beautiful meet. The natural and supernatural both appear. All parts symbolize the passion of Christ. If the crypt speaks of death, the lofty and vaulted roof and the beautiful pointed arches, and the cheerful window, and the jubilant chants speak of life. “The old church reminds one of the Christ that lay in the tomb; the new, of the Christ who arose the third day.” The old fosters meditation and silence; the new kindles the imagination, by its variety of perspective arrangement and mystic representation,–still reverential, still expressive of consecrated sentiments, yet more cheerful. The foliated shaft, the rich tracery of the window, the graceful pinnacle, the Arabian gorgeousness of the interior,–as if the crusaders had learned something from the East,–the innumerable shrines and pictures, the variegated marbles of the altar, with its vessels of silver and gold, the splendid dresses of the priests, the imposing character of the ritualism, the treasures lavished everywhere, all speak greater independence, wealth, and power. The church takes the place of all amusements. Its various attractions draw together the people from their farms and shops. They are gaily dressed, as if they were attending a festival. Their condition is so improved that they have time for holidays. And these the Church multiplies; for perpetual toil is the grave of intellect. The people must have rest, amusement, excitement. All these things the Catholic Church gives, and consecrates. Crusader, baron, knight, priest, peasant, all resort to the church for benedictions. Women too are there, and in greater numbers; and they linger for the confessional. When the time comes that women stay away from church, like busy, preoccupied, sceptical men, then let us be on the watch for some great catastrophe, since practical paganism will then be restored, and the angels of light will have left the earth.

Paris and its neighborhood was the cradle of this new development of architecture which we wrongly call the Gothic, even as Paris was the centre of the new-born intelligence of the era. The word “Gothic” suggests destructive barbarism: the English, French, and Germans descended chiefly from Normans, Saxons, and Burgundians. This form of church architecture rapidly spreads to Germany, England, and Spain. The famous Suger, the minister of a powerful king, built the abbey of St. Denis. The churches of Rheims, Paris, and Bourges arose in all their grandeur. The façade of Rheims is the most significant example of the wonderful architecture of the thirteenth century. In the church of Amiens you see the perfection of the so-called Gothic,–so graceful are its details, so dazzling is its height. The central aisle is one hundred and thirty-two feet in altitude,–only surpassed by that of Beauvais, which is fourteen feet higher. It was then that the cathedral of Rouen was built, with its elegant lightness,–a marvel to modern travellers. Soon after, the cathedral of Cologne appears, more grand than either,–but left unfinished,–with its central aisle forty-four feet in width, rising one hundred and forty feet into the air, with its colossal towers, intended to support the slender openwork spires, five hundred and twenty feet in height. The whole church is five hundred and thirty-two feet in length. I confess this church made a greater impression on my mind than did any Gothic church in Europe,–more, even, than Milan, with its unnumbered pinnacles and statues and its marble roof. I could not rest while surveying its ten thousand wonders,–so much lightness combined with strength; so grand, and yet so cheerful; so exquisitely proportioned, so complicated in details, and yet a grand unity; a glorious and fit temple for the reverential worship of the Deity. Oh, how grand are those monuments which were designed to last through ages, and which are consecrated, not to traffic, not to pleasure, not to material wealth, but to the worship of that Almighty God to whom every human being is personally responsible!

I cannot enumerate the churches of Mediaeval Europe,–built possibly by the Freemasons, certainly by men familiar with all that is practical in their art, with all that is hallowed and poetical. I glance at the English cathedrals, built during this epoch,–the period of the Crusades and the revival of learning.

And here I allude to the man who furnishes me with a text to my discourse,–William of Wykeham, chancellor and prime minister of Edward III., the contemporary of Chaucer and Wyclif,–who flourished in the fourteenth century, and who built Winchester Cathedral; a great and benevolent prelate, who also founded other colleges and schools. But I merely allude to him, since my subject is the art to which he gave an impulse, rather than any single individual. No one man represents church architecture any more appropriately than any one man represents the Feudal system, or Monasticism, or the Crusades, or the French Revolution.

I do not think the English cathedrals are equal to those of Cologne, Rheims, Amiens, and Rouen; but they are full of interest, and they have varied excellences. That of Salisbury is the only one which is of uniform style. Its glory is in its spire, as that of Lincoln is in its west front, and that of Westminster is in its nave. Gloucester is celebrated for its choir, and York for its tower. In all are beautiful vistas of pillars and arches. But they lack the inspiration of the Catholic Church. They are indeed hoary monuments, petrified mysteries, a “passion of stone,” as Michelet speaks of the marble histories which will survive his rhapsodies. They alike show the pilgrimage of humanity through gloomy centuries. If their great wooden screens were removed, which separate the choir from the nave, the cathedrals doubtless would appear to more advantage, and especially if they were filled with altars and shrines and pictures, and lighted candles on the altars,–filled also with crowds of worshippers, reverent before the gorgeously attired ministers of Divine Omnipotence, and excited by transporting chants, and the various appeals to sense and imagination. The reason must be assisted by the imagination, before the mind can revel in the glories of Gothic architecture. Imagination intensifies all our pleasures, even those of sense; and without imagination–yea, a memory stored with the pious deeds of saints and martyrs in bygone ages–a Gothic cathedral is as much a sealed book as Wordsworth is to Taine. The Protestant tourist from Michigan or Pennsylvania can “do” any cathedral in two hours, and wonder why they make such a fuss about a church not half so large as the New York Central Railroad station. The wonders of cathedrals must be studied, like the glories of a landscape, with an eye to the beautiful and the grand, cultured and practised by the contemplation of ideal excellence, when the mind summons the imagination to its aid, with all the poetry and all the history which have been learned in a life of leisure and study. How different the emotions of a Ruskin or a Tennyson, in surveying those costly piles, from those of a man fresh from a distillery or from a warehouse of cotton fabrics, or even from those of many fashionable women, whose only aesthetic accomplishment is to play languidly and mechanically on an instrument, and whose only intellectual achievement is to have devoured a dozen silly novels in the course of a summer spent in alternate sleep and dalliance! Nor does familiarity always give a zest to the pleasure which arises from the creations of art or the glories of nature. The Roman beggar passes the Coliseum or St. Peter’s without notice or enjoyment, as a peasant sees unmoved the snow-capped mountains of Switzerland or the beautiful lakes of Killarney. Said sorrowfully my guide up the Rhigi, “I wish I lived in Holland, for there are men there.” Yet there are those whom the ascent of Rhigi and the ruined monuments of ancient Rome would haunt for a lifetime, in whose memory they would be perpetually fresh, never to pass away, any more than the looks and the vows of early love from the mind of a sentimental woman.

The glorious old architecture whose peculiarity was the pointed arch, flourished only about three hundred years in its purity and matchless beauty. Then another change took place. The ideal became lost in meaningless ornaments. The human figure peoples the naked walls. “Man places his own image everywhere…. The tomb rises like a mausoleum in side chapels. Man is enthroned, not God.” The corruption of the art keeps pace with the corruption of the Papacy and the discords of society. In the fourteenth century the Mediaeval has lost its charm and faith.

And then sets in the new era, which begins with Michael Angelo. It is marked by the revival of Greek art and Greek literature. At Florence reign the Medici. On the throne of Saint Peter sits an Alexander VI. or a Julius II. Genoa is a city of merchant-palaces. Museums are collected of the excavated remains of Roman antiquity. Everybody kindles with the contemplation of the long-buried glories of a classic age; everybody reads the classic authors: Cicero is a greater oracle than Saint Augustine. Scholars flock to Italy. The popes encourage the growing taste for Pagan philosophy. Ancient art regains her long-abdicated throne, and wields her sceptre over the worshippers of the Parthenon and the admirers of Aeschylus and Thucydides. With the revived statues of Greece appear the most beautiful pictures ever produced by the hand of man; and with pictures and statues architecture receives a new development. It is the blending of the old Greek and Roman with the Gothic, and is called the Renaissance. Michael Angelo erects St. Peter’s, the heathen Pantheon, on the intersection of Gothic nave and choir and transept; a glorious dome, more beautiful than any Gothic spire or tower, rising four hundred and fifty feet into the air. And in the interior are classic circular arches and pillars, so vast that one is impressed as with great feats of engineering skill. All that is variegated in marbles adorns the altars; all that is bewitching in paintings is transferred to mosaics. And this new style of Italy spreads into France and England. Sir Christopher Wren builds St. Paul’s,–more Grecian than Gothic,–and fills London with new churches, not one of which is Gothic, and all different. The brain is bewildered in attempting to classify the new and ever-shifting forms of the revived Italian. And so for three hundred years the architects mingle the Gothic with the classical, until now a mongrel architecture is the disgrace of Europe; varied but not expressive, resting on no settled principles, neither on vertical nor on horizontal lines,–blended together, sometimes Grecian porticos on Elizabethan structures, spires resting not on towers but roofs, Byzantine domes on Grecian temples, Greek columns with Lombard arches, flamboyant panelling, pendant pillars from the roof, all styles mixed up together, Corinthian pilasters acting as Gothic buttresses, and pointed arches with Doric friezes,–a heap of diverse forms, alien alike from the principles of Wykeham and Vitruvius.

And this varied mongrel style of architecture corresponds with the confused civilization of the period,–neither Greek nor Gothic, but a mixture of both; intolerant priests wrangling with pagan sceptics and infidels,–Aquaviva with Pascal, the hierarchy of the French Church with Voltaire and Rousseau, Protestant divines with the Catholic clergy; Geneva and Rome compromising at Oxford, the authority of the Fathers made antagonistic to the authority of popes, new vernacular tongues supplanting Latin in the universities; everywhere war on the Middle Ages, without full emancipation from their dogmas, ancient paganism made to uphold the Church, an unbounded activity of intellect casting off all established rules, the revival of the old Greek republics, democracy asserting its claim against absolute power; nothing settled, nothing at rest, but motion in every direction,–science combating faith, faith spurning reason, humanity arrogating divinity, the confusion of races, Babel towers of vanity and pride in the new projected enterprises, Christian nations embroiled in constant wars, gold and silver set up as idols, the rise of new powers in the shapes of new industries and new inventions, commerce filling the world with wealth, armies contending for rights as well as for the aggrandizement of monarchies: was there ever such a simmering and boiling and fermenting period of activities since the world began? In such a wild and tumultuous agitation of passions and interests and ideas, how could Art reappear either in the classic severity of Greek temples or the hoary grandeur of Mediaeval cathedrals? In this jumble we look for new creations, but no creations in art appear, only fantastic imitations. There is no creation except in a new field, that of science and mechanical inventions,–where there is the most extraordinary and astonishing development of human genius ever seen on earth, but “of the earth earthy,” aiming at material good. Architecture itself is turned into great feats of engineering. It does not span the apsis of a church; it spans rivers and valleys. The church, indeed, passes out of mind, if not out of sight, in the new material age, in the multiplication of bridges and gigantic reservoirs,–old Rome brought back again in its luxuries.

And yet the exactness of science and the severity of criticism–begun fifty years ago, in the verification of principles–produce a better taste. Architects have sought to revive the purest forms of both Gothic and Grecian. If they could not create a new style, they would imitate the old: as in philosophy, they would go round in the old circles. As science revives the atoms of Democritus, so art would reproduce the ideas of Phidias and Vitruvius, and even the poetry and sanctity of the Middle Ages. Within fifty years Christendom has been covered with Gothic churches, some of which are as beautiful as those built by Freemasons. The cathedrals have been copied rigidly, even for village churches. The Parthenon reappears in the Madeleine. We no longer see, as in the eighteenth century, Gothic spires on Roman basilicas, or Grecian porticos ornamenting Norman towers. The various styles of two thousand years are not mixed up in the same building. We copy either the horizontal lines of Paganism or the vertical lines of the ages of Faith. No more harmonious Gothic edifice was ever erected than the new Catholic cathedral of New York.

The only absurdity is seen when radical Protestantism adopts the church of pomps and liturgies. When the Reformation was completed, men sought to build churches where they could hear the voice of the preacher; for the mission of Protestantism is to teach, not to sing. Protestantism glories in its sermons as much as Catholicism in its chants. If the people wish to return again to ritualism, let them have the Gothic church. If they wish to be electrified by eloquence, let them have a basilica, for the voice of the preacher is lost in high and vaulted roofs. If they wish to join in the prayers and the ceremonies of the altar, let them have the clustering pillars and the purple windows.

Everything turns upon what is meant by a church. What is it for? Is it for liturgical services, or is it for pulpit eloquence? Solve that question, and you solve the Reformation. “My house,” saith the Divine Voice, “shall be called the house of prayer.” It is “by the foolishness of preaching,” said Paul, that men are saved.

If you will have the prayers of the Middle Ages and the sermons of the Reformation both together, then let the architects invent a new style, which shall allow the blending of prayer and pulpit eloquence. You cannot have them both in a Grecian temple, or in a Gothic church. You must combine the Parthenon with Salisbury, which is virtually a new miracle of architecture. Will that miracle be wrought? I do not know. But a modern Protestant church, with all the wonders of our modern civilization, must be something new,–some new combination which shall be worthy of the necessity of our times. This is what the architect must now aspire to accomplish; he must produce a house in which one can both hear the sermon, and be stimulated by inspiring melodies,–for the Church must have both. The psalms of David and the chants of Gregory must be blended with the fervid words of a Chrysostom and a Chalmers.

This, at least, should be borne in mind: the church edifice must be adapted to the end designed. The Gothic architects adapted their vaults and pillars to the ceremonies of the Catholic ritual. If it is this you want, then copy Gothic cathedrals. But if it is preaching you want, then restore the Grecian temple,–or, better still, the Roman theatre,–where the voice of the preacher is not lost either in Byzantine domes or Gothic vaults, whose height is greater than their width. The preacher must draw by the distinctness of his tones; for every preacher has not the musical voice of Chrysostom, or the electricity of St. Bernard. He can neither draw nor inspire if he cannot be heard; he speaks to stones, not to living men or women. He loses his power, and is driven to chants and music to keep his audience from deserting him. He must make his choir an orchestra; he must hide himself in priestly vestments; he must import opera singers to amuse and not instruct. He cannot instruct when he cannot be heard, and heard easily. Unless the people catch every tone of his voice his electricity will be wasted, and he will preach in vain, and be tired out by attempting to prevent echoes. The voice of Saint Paul would be lost in some of our modern fashionable churches. Think of the absurdity of Baptists and Methodists and Presbyterians affecting to restore Gothic monuments, when the great end of sacred eloquence is lost in those devices which appeal to sense. Think of the folly of erecting a church for eight hundred people as high as Westminster Abbey. It is not the size of a church which prevents the speaker from being heard,–it is the disproportion of height with breadth and length, and the echoes produced by arcades. Spurgeon is heard easily by seven thousand people, and Talmage by six thousand, and Dr. Hall by four thousand, because the buildings in which they preach are adapted to public speaking. Those who erect theatres take care that a great crowd shall be able to catch even the whispers of actors. What would you think of the good sense and judgment of an architect who should construct a reservoir that would leak, in order to make it ornamental; or a schoolhouse without ventilation; or a theatre where actors could only be seen; or a hotel without light and convenient rooms; or a railroad bridge which would not support a heavy weight?

A Protestant church is designed, no matter what the sect may be to which it belongs, not for poetical or aesthetic purposes, not for the admiration of architectural expenditures, not even for music, but for earnest people to hear from the preacher the words of life and death, that they may be aroused by his enthusiasm, or instructed by his wisdom; where the poor are not driven to a few back seats in the gallery; where the meeting is cheerful and refreshing, where all are stimulated to duties. It must not be dark, damp, and gloomy, where it is necessary to light the gas on a foggy day, and where one must be within ten feet of the preacher to see the play of his features. Take away facilities for hearing and even for seeing the preacher, and the vitality of a Protestant service is destroyed, and the end for which the people assemble is utterly defeated. Moreover, you destroy the sacred purposes of a church if you make it so expensive that the poor cannot get sittings. Nothing is so dull, depressing, funereal, as a church occupied only by prosperous pew-holders, who come together to show their faces and prove their respectability, rather than to join in the paeans of redemption, or to learn humiliating lessons of worldly power before the altar of Omnipotence. To the poor the gospel is preached; and it is ever the common people who hear most gladly gospel truth. Ah, who are the common people? I fancy we are all common people when we are sick, or in bereavement, or in adversity, or when we come to die. But if advancing society, based on material wealth and epicurean pleasure, demands churches for the rich and churches for the poor,–if the lines of society must be drawn somewhere,–let those architects be employed who understand, at least, the first principles of their art. I do not mean those who learn to draw pictures in the back room of a studio, but conscientious men, if you cannot find sensible men. And let the pulpit itself be situated where the people can hear the speaker easily, without straining their eyes and ears. Then only will the speaker’s voice ring and kindle and inspire those who come together to hear God Almighty’s message; then only will he be truly eloquent and successful, since then only does his own electricity permeate the whole mass; then only can he be effective, and escape the humiliation of being only a part of a vain show, where his words are disregarded and his strength is wasted in the echoes of vaults and recesses copied from the gloomy though beautiful monuments of ages which can never, never again return, any more than can “the granite image worship of the Egyptians, the oracles of Dodona, or the bulls of the Mediaeval popes.”

Authorities.

Fergusson’s History of Architecture; Durand’s Parallels; Eastlake’s Gothic and Revival; Ruskin, Daly, and Penrose; Britton’s Cathedrals and Architectural Antiquities; Pugin’s Specimens and Examples of Gothic Architecture; Rickman’s Styles of Gothic Architecture; Street’s Gothic Architecture in Spain; Encyclopaedia Britannica (article Architecture).