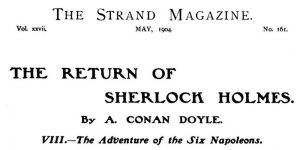

The Fate of the Evangeline by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Fate of the Evangeline I

The Fate of the Evangeline II

The Fate of the Evangeline III

The Fate of the Evangeline III

The moorings had been at the south end of the island, and as the wind was cast, we headed straight out to the Atlantic. I did not put up any more sail yet, for it would be seen by those we had left, and I wished at present to leave them under the impression that the yacht had drifted away by accident, so that if they found any means of communicating with the mainland they might start upon a wrong scent. After three hours, however, the island being by that time upon the extreme horizon, I hoisted the mainsail and jib.

I was busily engaged in tugging at the halliards, when Miss

Forrester, fully dressed, stepped out of her cabin and came upon deck. I shall never forget the expression of utter astonishment which came over her beautiful features when she realised that she was out at sea and with a strange companion. She gazed at me with, at first, terror as well as surprise. No doubt, with my long dark hair and beard, and tattered clothing, I was not a very reassuring object.

The instant I opened my lips to address her, however, she recognised me, and seemed to comprehend the situation.

“Mr. Gibbs,” she cried. “Jack, what have you done? You have carried me away from Ardvoe. Oh, take me back again! What will my poor father do?”

“He’s all right,” I said. “He is hardly so very thoughtful about you, and may not mind doing without you now for a little.” She was silent for a while, and leaned against the companion rail, endeavouring to collect herself.

“I can hardly realise it,” she said, at last. “How could you have come here, and why are we at sea? What is your object, Jack? What are you about to do?”

“My only object is this,” I said, tremblingly, coming up closer to her. “I wished to be able to have a chance of talking to you alone without interruption. The whole happiness of my life depends upon it. That is why I have carried you off like this. All I ask you to do is to answer one or two questions, and I will promise to do your bidding. Will you do so?”

“Yes,” she said, “I will.”

She kept her eyes cast down and seemed to avoid my gaze. “Do you love this man Scholefield?” I asked.

“No,” she answered, with decision.

“Will you ever marry him?”

“No,” she answered again.

“Now, Lucy,” I said, “speak the truth fearlessly, let me entreat you, for the happiness of both of us depends upon it. Do you still love me?”

She never spoke, but she raised her head and I read her answer in her eyes. My heart overflowed with joy.

“Then, my darling,” I cried, taking her hand, “if you love me and I love you, who is to come between us? Who dare part us?”

She was silent, but did not attempt to escape from my arm.

“Not your father,” I said. “He has no power or right over you. You know well that if one who was richer than Scholefield appeared to-morrow he would bid you smile upon him without a thought as to your own feelings. You can in such circumstances owe him no allegiance as to giving yourself for mere mercenary reasons to those you in heart abhor.”

“You are right, Jack. I do not,” she answered, speaking very gently, but very firmly. “I am sorry that I left you as I did in St. James’s Park. Many a time since I have bitterly regretted it. Still at all costs I should have been true to my father if he had been true to me. But he has not been so. Though he knows my dislike to Mr. Scholefield he has continually thrown us together as on this yachting excursion, which was hateful to me from the first. Jack,” she continued, turning to me, “you have been true to me through everything. If you still love me I am yours from this moment—yours entirely and for ever. I will place myself in their power no more.”

Then in that happy moment I was repaid for all the long months of weariness and pain. We sat for hours talking of our thoughts and feelings since our last sad parting, while the boat drifted aimlessly among the tossing waves, and the sails flapped against the spars above our heads. Then I told her how I had swum off and cut the cable of the Evangeline.

“But, Jack,” she said, “you are a pirate; you will be prosecuted for carrying off the boat.”

“They may do what they like now,” I said, defiantly; “I have gained you, in carrying off the boat.”

“But what will you do now?” she asked.

“I will make for the north of Ireland,” I said; “then I shall put you under the protection of some good woman until we can get a special licence and be able to defy your father. I shall send the Evangeline back to Ardvoe or to Skye. We are going to have some wind, I fear. You will not be afraid, dear?”

“Not while I am with you,” she answered, calmly.

The prospect was certainly not a reassuring one. The whole eastern horizon was lined by great dark clouds, piled high upon each other, with that lurid tinge about them which betokens violent wind. Already the first warning blasts came whistling down upon us, heeling our little craft over till her gunwale lay level with the water. It was impossible to beat back to the Scotch coast, and our best chance of safety lay in running before the gale. I took in the topsail and flying-jib, and reefed down the mainsail; then I lashed everything moveable in case of our shipping a sea. I wished Lucy to go below to her cabin, but she would not leave me, and remained by my side.

As the day wore on the occasional blasts increased into a gale, and the gale into a tempest. The night set in dark and dreary, and still we sped into the Atlantic. The Evangeline rose to the seas like a cork, and we took little or no water aboard. Once or twice the moon peeped out for a few moments between the great drifting cloud-banks. Those brief intervals of light showed us the great wilderness of black, tossing waters which stretched to the horizon. I managed to bring some food and water from the cabin while Lucy held the tiller, and we shared it together. No persuasions of mine could induce her to leave my side for a moment.

With the break of day the wind appeared to gain more force than ever, and the great waves were so lofty that many of them rose high above our masthead. We staggered along under our reefed sail, now rising upon a billow, from which we looked down on two great valleys before and behind us, then sinking down into the trough of the sea until it seemed as if we could never climb the green wall beyond. By dead reckoning I calculated that we had been blown clear of the north coast of Ireland. It would have been madness to run towards an unknown and dangerous shore in such weather, but I steered a course now two more points to the south, so as not to get blown too far from the west coast in case that we had passed Malin Head. During the morning Lucy thought that she saw the loom of a fishing-boat, but neither of us were certain, for the weather had become very thick. This must have been the boat of the man Mullins, who seems to have had a better view of us than we had of him.

All day (our second at sea) we continued to steer in a south-westerly direction. The fog had increased and become so thick that from the stern we could hardly see the end of the bowsprit. The little vessel had proved herself a splendid sea boat, and we had both become so reconciled to our position, and so confident in her powers, that neither of us thought any longer of the danger of our position, especially as the wind and sea were both abating. We were just congratulating each other upon this cheering fact, when an unexpected and terrible catastrophe overtook us.

It must have been about seven in the evening, and I had gone down to rummage in the lockers and find something to eat, when I heard Lucy give a startled cry above me. I sprang upon deck instantly. She was standing up by the tiller peering out into the mist.

“Jack,” she cried. “I hear voices, There is some one close to us.”

“Voices!” I said; “impossible. If we were near land we should hear the breakers.”

“Hist!” she cried, holding up her hand. “Listen!”

We were standing together straining our ears to catch every sound, when suddenly and swiftly there emerged from the fog upon our starboard bow a long line of Roman numerals with the figure of a gigantic woman hovering above them. There was no time for thought or preparation. A dark loom towered above us, taking the wind from our sails, and then a great vessel sprang upon us out of the mist as a wild beast might upon its prey. Instinctively, as I saw the monster surging down upon us, I flung one of the life-belts, which was hanging round the tiller, over Lucy’s head, and seizing her by the waist, I sprang with her into the sea.

What happened after that it is hard to tell. In such moments all idea of time is lost. It might have been minutes or it might have been hours during which I swam by Lucy’s side, encouraging her in every possible way to place full confidence in her belt and to float without struggling. She obeyed me to the letter, like a brave girl as she was. Every time I rose to the top of a wave I looked around for some sign of our destroyer, but in vain. We joined our voices in a cry for aid, but no answer came back except the howling of the wind. I was a strong swimmer, but hampered with my clothes my strength began gradually to fail me. I was still by Lucy’s side, and she noticed that I became feebler.

“Trust to the belt, my darling, whatever happens,” I said.

She turned her tender face towards me.

“If you leave me I shall slip it off,” she answered.

Again I came to the top of a great roller, and looked round. There was nothing to be seen. But hark! what was that? A dull clanking noise came on my ears, which was distinct from the splash of the sea. It was the sound of oars in rowlocks. We gave a last feeble cry for aid. It was answered by a friendly shout, and the next that either of us remember was when we came to our senses once more and found ourselves in warm and comfortable berths with kind anxious faces around us. We had both fainted while being lifted into the boat.

The vessel was a large Norwegian sailing barque, the Freyja, of five hundred tons, which had started five days before from Bergen, and was bound for Adelaide in Australia. Nothing could exceed the kindness of Captain Thorbjorn and his crew to the two unfortunates whom they had picked out of the Atlantic Ocean. The watch on deck had seen us, but too late to prevent a collision. They had at once dropped a boat, which was about to return to the ship in despair, when that last cry reached their ears.

Captain Thorbjorn’s wife was on board, and she at once took my dear companion under her care. We had a pleasant and rapid voyage to Adelaide, where we were duly married in the presence of Madame Thorbjorn and of all the officers of the Freyja.

After our marriage I went upcountry, and having taken a large farm there, I remained a happy and prosperous man. A sum of money was duly paid over to the firm of Scholefield, coming they knew not whence, which represented the value of the Evangeline.

One of the first English mails which followed us to Australia announced the death of Colonel Forrester, who fractured his skull by falling down the marble steps of a Glasgow hotel. Lucy was terribly grieved, but new associations and daily duties gradually overcame her sorrow.

Since then neither of us have anything to bind us to the old country, nor do we propose to return to it. We read the English periodicals, however, and have amused ourselves from time to time in noticing the stray allusions to the yacht Evangeline, and the sad fate of the young lady on board her. This short narrative of the real facts may therefore prove interesting to some few who have not forgotten what is now an old story, and some perhaps to whom the circumstances are new may care to hear a strange chapter in real life.

The Fate of the Evangeline by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Fate of the Evangeline I

The Fate of the Evangeline II

The Fate of the Evangeline III