Buried Treasures by Bram Stoker

Buried Treasures Chapter I The Old Wreck

Buried Treasures Chapter II Wind and Tide

Buried Treasures Chapter III The Iron Chest

Buried Treasures Chapter IV Lost and Found

Buried Treasures Chapter III The Iron Chest

The days that intervened were long to both men.

To Robert they were endless; even the nepenthe of continued hard work could not quiet his mind. Distracted on one side by his forbidden love for Ellen, and on the other by the expected fortune by which he might win her, he could hardly sleep at night. When he did sleep he always dreamed, and in his dreams Ellen and the wreck were always associated. At one time his dream would be of unqualified good fortune – a vast treasure found and shared with his love; at another, all would be gloom, and in the search for the treasure he would endanger his life, or, what was far greater pain, forfeit her love.

However, it is one consolation, that, whatever else may happen in the world, time wears on without ceasing, and the day longest expected comes at last.

On the evening of the 24th December, Tom and Robert took their way to Dollymount in breathless excitement.

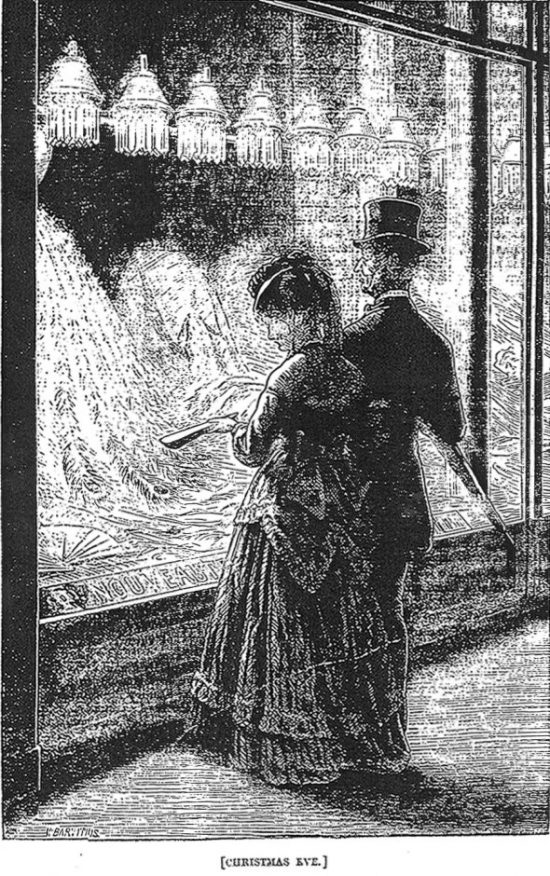

As they passed through town, and saw the vast concourse of people all intent on one common object – the preparation for the greatest of all Christian festivals – the greatest festival, which is kept all over the world, wherever the True Light has fallen, they could not but feel a certain regret that they, too, could not join in the throng. Robert’s temper was somewhat ruffled by seeing Ellen leaning on the arm of Tomlinson, looking into a brilliantly-lighted shop window, so intently, that she did not notice him passing. When they had left the town, and the crowds, and the overflowing stalls, and brilliant holly-decked shops, they did not so much mind, but hurried on.

So long as they were within city bounds, and even whilst there were brightly-lit shop windows, all seemed light enough. When, however, they were so far from town as to lose the glamour of the lamplight in the sky overhead, they began to fear that the night would indeed be too dark for work.

They were prepared for such an emergency, and when they stood on the slope of sand, below the dunnes, they lit a dark lantern and prepared to cross the sands. After a few moments they found that the lantern was a mistake. They saw the ground immediately before them so far as the sharp triangle of light, whose apex was the bulls-eye, extended, but beyond this the darkness rose like a solid black wall. They closed the lantern, but this was even worse, for after leaving the light, small though it was, their eyes were useless in the complete darkness. It took them nearly an hour to reach the wreck.

At last they got to work, and with hammer and chisel and saw commenced to open the treasure ship.

The want of light told sorely against them, and their work progressed slowly despite their exertions. All things have an end, however, and in time they had removed several planks so as to form a hole some four feet wide, by six long – one of the timbers crossed this; but as it was not in the middle, and left a hole large enough to descend by, it did not matter.

It was with beating hearts that the two young men slanted the lantern so as to turn the light in through the aperture. All within was black, and not four feet below them was a calm glassy pool of water that seemed like ink. Even as they looked this began slowly to rise, and they saw that the tide had turned, and that but a few minutes more remained. They reached down as far as they could, plunging their arms up to their shoulders in the water, but could find nothing. Robert stood up and began to undress.

“What are you going to do?” said Tom.

“Going to dive – it is the only chance we have.”

Tom did not hinder him, but got the piece of rope they had brought with them and fastened it under Robert’s shoulders and grasped the other end firmly. Robert arranged the lamp so as to throw the light as much downwards as possible, and then, with a silent prayer, let himself down through the aperture and hung on by the beam. The water was deadly cold – so cold, that, despite the fever heat to which he was brought through excitement, he felt chilled. Nevertheless he did not hesitate, but, letting go the beam, dropped into the black water.

“For Ellen,” he said, as he disappeared.

In a quarter of a minute he appeared again, gasping, and with a convulsive effort climbed the short rope, and stood beside his friend.

“Well?” asked Tom, excitedly.

“Oh-h-h-h! good heavens, I am chilled to the heart. I went down about six feet, and then touched a hard substance. I felt round it, and so far as I can tell it is a barrel. Next to it was a square corner of a box, and further still something square made of iron.”

“How do you know it is iron?”

“By the rust. Hold the rope again, there is no time to lose; the tide is rising every minute, and we will soon have to go.”

Again he went into the black water and this time stayed longer. Tom began to be frightened at the delay, and shook the rope for him to ascend. The instant after he appeared with face almost black with suffused blood. Tom hauled at the rope, and once more he stood on the bottom of the vessel. This time he did not complain of the cold. He seemed quivering with a great excitement that overcame the cold. When he had recovered his breath he almost shouted out –

“There’s something there. I know it – I feel it.”

“Anything strange?” asked Tom, in fierce excitement.

“Yes, the iron box is heavy – so heavy that I could not stir it. I could easily lift the end of the cask, and two or three other boxes, but I could not stir it.”

Whilst he was speaking, both heard a queer kind of hissing noise, and looking down in alarm saw the water running into the pool around the vessel. A few minutes more and they would be cut off from shore by some of the tidal streams. Tom cried out:

“Quick, quick! or we shall be late. We must put down the beams before the tide rises or it will wash the hold full of sand.”

Without waiting even to dress, Robert assisted him and they placed the planks on their original position and secured them with a few strong nails. Then they rushed away for shore. When they had reached the sand-hill, Robert, despite his exertions, was so chilled that he was unable to put on his clothes.

To bathe and stay naked for half an hour on a December night is no joke.

Tom drew his clothes on him as well as he could, and after adding his overcoat and giving him a pull from the flask, he was something better. They hurried away, and what with exercise, excitement, and hope were glowing when they reached home.

Before going to bed they held a consultation as to what was best to be done. Both wished to renew their attempt as they could begin at half-past seven o’clock; for although the morrow was Christmas Day, they knew that any attempt to rescue goods from the wreck should be made at once. There were now two dangers to be avoided – rough weather and the drifting of the sand – and so they decided that not a moment was to be lost.

At the daybreak they were up, and the first moment that saw the wreck approachable found them wading out towards it. This time they were prepared for wet and cold. They had left their clothes on the beach and put on old ones, which, even if wet, would still keep off the wind, for a strong, fitful breeze was now blowing in eddies, and the waves were beginning to rise ominously. With beating hearts they examined the closed-up gap; and, as they looked, their hopes fell. One of the timbers had been lifted off by the tide, and from the deposit of sand in the crevices, they feared that much must have found its way in. They had brought several strong pieces of rope with them, for their effort to-day was to be to lift out the iron chest, which both fancied contained a treasure.

Robert prepared himself to descend again. He tied one rope round his waist, as before, and took the other in his hands. Tom waited breathlessly till he returned. He was a long time coming up, and rose with his teeth chattering, but had the rope no longer with him. He told Tom that he had succeeded in putting it under the chest. Then he went down again with the other rope, and when he rose the second time, said that he had put it under also, but crossing the first. He was so chilled that he was unable to go down a third time. Indeed, he was hardly able to stand so cold did he seem; and it was with much shrinking of spirit that his friend prepared to descend to make the ropes fast, for he knew that should anything happen to him Robert could not help him up. This did not lighten his task or serve to cheer his spirits as he went down for the first time into the black water. He took two pieces of rope; his intention being to tie Robert’s ropes round the chest, and then bring the spare ends up. When he rose he told Robert that he had tied one of the ropes round the box, but had not time to tie the others. He was so chilled that he could not venture to go down again, and so both men hurriedly closed the gap as well as they could, and went on shore to change their clothes. When they had dressed, and got tolerably warm, the tide had begun to turn, and so they went home, longing for the evening to come, when they might make the final effort.