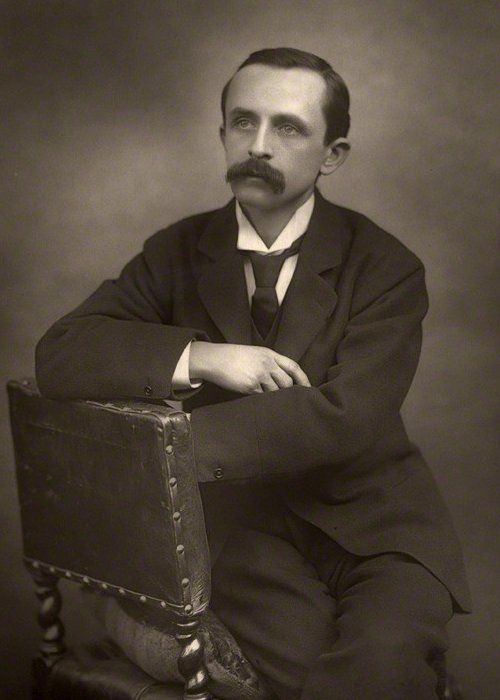

Half an Hour Play by James Matthew Barrie

HALF AN HOUR PLAY

First performance: 1913

First publication: 1928

HALF AN HOUR PLAY CHARACTERS

Garson

Lady Lilian

Hugh Paton

Susie

Dr. Brodie

Withers

Redding

Mrs. Redding

NOTE : The list of characters is provided for the convenience of readers, but was not included in the original book.

HALF AN HOUR PLAY

Mr. Garson, who is a financier, and his young wife, the lovely Lady Lilian, are in their mansion near Park Lane, but they are not at home this evening to the public eye; they are in the midst of a brawl which, it may be hoped, does not show them at their best. There is such a stirring time before them, and only half an hour for it, that we must not keep them waiting. Indeed they have so much to do that we challenge them to do it.

Lady Lilian (a frozen flower). Why don’t you strike me, Richard? I am a woman, and there is no one within call.

Garson. A woman! You useless thing, that is just what you are not.

(It is evidently his honest if mistaken opinion, and he pushes her from him so roughly that she lies on the couch as she fell, in a touching but perhaps rather impertinent little heap.)

Lilian (who, though a dear woman to some, has a genius for putting her finger on the raw of those she does not favour). How strong you are, husband mine! No wonder I love you! Now as I have told you why I love you, won’t you tell me why you love me?

(He fumes inarticulately while she takes off her hat and coat, perhaps in search of that homey feeling.)

How you have ruffled me! (She considers her frock.) You know, I can’t make up my mind whether green is really my colour. What do you think? Which colour do you like best to knock me about in, Richard?

Garson (with his fists clenched though they are not upraised). You take care!

Lilian (as he stamps the floor). Do you mind telling me what all this scene has been about?

Garson. You have me there. But how does it matter what it is that sets a pair like you and me saying what we think of each other?

Lilian. True. But we knew what we thought of each other before.

Garson. We did. And I’ve said to that father of yours——

Lilian. By the way, I never heard how much you paid Pops for me?

Garson. One way or another, a good twenty thousand.

Lilian. I can’t help feeling proud.

Garson. If I could have got you for half I wouldn’t have had you.

Lilian. How like you to say that, Richard! Still, there are other pretties for whom you could have had the satisfaction of paying more. There must have been some—dear reason—why you flung the handkerchief to me?

Garson. Your rotten old families, all so poor and so well turned out. The come-on look in the melting eyes of you, and the disdain of you. I suppose they went to my head. You were the worst, so I chose you.

Lilian (clapping her hands). I won!

Garson. Oh, you didn’t need to come to me unless you liked.

Lilian (shivering). I admit that. It was your money that brought me.

Garson. Quite so.

Lilian (with a sincerity that makes us hopeful of her). I’m sorry, Richard, for both of us.

Garson. Pooh!

Lilian. You must at least allow that I never pretended it was anything but your wealth that drew me.

Garson. I never wanted it to be anything else.

Lilian. How like you again! Perhaps that is even some little excuse—though not very much—for me.

Garson (sneering). Soft sawder!

Lilian. I dare say. (Surveying the man with curiosity). Why don’t we end it?

Garson (bellowing). Do you know whom you are talking to? With my name in the City——

Lilian. Of course. But if you won’t, Richard, has it never struck you that some day I——

Garson (grinning). Never!

Lilian. You have a mighty faith in me.

Garson. Mighty.

Lilian. May I ask why?

(He comes up to her and taps her bodice.)

Garson. In this expensive little breast you know why. (In case there should be any misunderstanding he slaps his pocket.)

Lilian. I see.

Garson. Tragic lot yours, isn’t it?

Lilian. More tragic than you understand.

Garson. Bought when you were too young to know what you were doing!

Lilian. Not so young but that I should have known.

Garson. Such a rare exquisite creature, too, as you know yourself to be.

Lilian (with abnegation). As I know I am not. But as I long to be. As I think I could be.

Garson. As you think you could be, had you married a better man.

Lilian. Mock me, you have some right, but it may be truer than you think.

Garson. It is what they tell you, I don’t doubt.

Lilian. Who tell me?

Garson. The live-on-papa cubs.

Lilian (shrugging her shoulders). If I were to let them tell me what they would like to say——

Garson (possibly with some penetration). You do, my pet, and when they have finished you tell them they mustn’t say it; and your lip trembles and one sad tear sits on your sweet eyes, the same little tear that comes when you have overdrawn your bank account.

Lilian. How you read me!

Garson. I think so. I think I know the stuff you are made of. I wouldn’t try heroics, Lilian; you can’t live up to them.

Lilian. I haven’t the courage, I suppose?

Garson. You have the pluck that let the French Jack-a-dandies go tripping to the guillotine; and perhaps my breed hasn’t. But when it comes to living you’ve got to live on us, my girl.

Lilian (rising and facing him). Oh, if—if——

Garson. If—if you were to show me! I am not nervous. In the end you will always be true to Number One. I have thought you out.

Lilian (on fire). If I did?

Garson. If you did—if you tried to play any game on me——

(He takes grip of her by the wrist.)

Lilian (in her earlier manner). Would it be the knife, Richard, or Desdemona’s pillow?

Garson. If you brought any shame on me, before I put you to the door I would—I would break you!

Lilian. If I did it I wouldn’t be here to break.

Garson. By the powers, it would be as well for you.

Lilian. Unless you wish to do the breaking now, please let go my wrist.

(He throws it from him, and their colloquy ends with these terrible words:)

Garson. Dinner at half-past, I suppose?

Lilian. I suppose so.

(When she is alone we see some great resolution struggling into life in her and adorning her. It means among other things, we may conclude, that she does not purpose joining him at dinner. She writes a brief letter, puts her wedding-ring in the envelope and deposits the explosive in the nearest drawer of his desk. On top of it she throws all the jewellery she is wearing and closes the drawer. She puts on her hat and coat, and after a last look in a glass at the face she is leaving behind her—the only face of her that Garson knows—she leaves his house.

Two hundred yards away is a mews, where odd brainy people—afterwards sorry for themselves—have here and there made romantic homes, all tiny but not all over the garages that have supplanted stables. This one where Hugh Paton lodges is a complete house, and we find him in a snug room, though it is only reached by a brief ladder which he frequently jumps. At present the room is in disorder, the fire extinguished by the masses of paper he has dumped on it, and he himself is tousled and in disarray. He has not quite finished an extensive packing, and has reached the point of wondering whether he should reopen that bulging bag to put those old football boots in it, or leave them for the good of the house. He is whistling gaily, with broken intervals in which his pipe is in his mouth, and he has a very honest face.

To him enters with a rush the little daughter of the house, whose heart he has won by lifting his hat to her in the mews. She has walked with more dignity ever since, and she is twelve.)

Susie. You will be stamping at me, sir, but there is a lady, and though I told her you were just putting on your muffler to start for Egypt, up she would come.

(Up she does come, and she is Lilian. When Susie sees how these two look at each other she knows all, and indeed more, and out of respect for Love she goes down the ladder on her tiptoes.)

Hugh (surprised, but with outstretched arms). You! Oh, my dear!

(She will not let him embrace her yet.)

Lilian (the soft-eyed, the tremulous). No, Hugh. Please listen to me first. You see I have changed my mind, and come after all. Yes, I am here to go with you, if you will have me still. But oh, my Hugh, let there be no mistake. Don’t have me, dear, if you would rather—rather not.

(He clasps her to him, and of course she was sure he would.)

It isn’t really a shock to you, is it? Hugh, you don’t despise me in your heart for coming?

Hugh. Dear, my dear!

Lilian (merely playing with the idea). You are so fond of Egypt—perhaps it would be lovelier for you to go back to it alone.

(We are sorry she says this, for she has put it into our own heads. They are about the same age, but as they sit there on one of his trunks he looks younger.)

Hugh (who is far from agreeing with us). Egypt, without you? Horrible!

Lilian. Was it seeming horrible before I came up the ladder?

Hugh (abashed). Inconceivable if it wasn’t.

Lilian. You were able to smoke.

Hugh. Mechanically. (He remembers guiltily that he was even whistling.) Lilian, that man packing wasn’t me. I only began to be again when you lit up the doorway. Tell me, what made you change your mind so suddenly?

Lilian. Not suddenly. I longed to go to you, but I was his wife. Hugh, did you hear me say I was his wife? What a lovely way of putting it!

Hugh. My wife now and always.

Lilian. The things he said to-night!

Hugh. There, there, that is all over. You wrote the letter?

Lilian. Yes, and left it for him.

Hugh. You said in it that it was to me you were coming? I asked that of you because I want it all to be above-board. I am not afraid of him.

Lilian. Yes, I said in it that I was going away with you, and I put his wedding-ring inside it. I have burned all my boats. Oh, Hugh, if it had turned out that you would rather not!

Hugh. A nice sort of gent I’d be.

Lilian. He thinks me a rotten, shallow creature. No, don’t interrupt. Perhaps I was so with him, dear. What was bad in each of us seemed to call to the other.

Hugh. If yours ever calls to me I won’t recognise the voice.

Lilian. He said that in any test I would always go where my bread was best buttered.

Hugh. He will see his mistake when he finds you have come to me. (He starts up) I say! We mustn’t be late. Not another word if you love me. Try to make these catches snap, while I sit on the trunk. What are you smiling at?

Lilian. I have just remembered, Hugh, that there were people coming to dinner to-night!

Hugh (rising triumphant from his struggle with the trunk). I have just remembered something more important. (With accusing finger) Woman, where is your trousseau?

Lilian. I have only what you see, my dear. Here is all the riches I bring you—four and sixpence. Please take care of my dowry for me, Hugh!

Hugh. You poor one! But what fun to buy you a trousseau at Brindisi—if not before.

(He rings.)

Lilian (catching his gaiety). Are you proposing to send out a servant to get a trousseau for me?

Hugh. What a capital idea! (As the little maid arrives) Susie, skip across to the nearest draper’s and buy me a trousseau.

Susie. A what, sir?

Hugh. I can only give you ten minutes—lots of time—sure to have them in stock—need of the age—all ready in Christmas hampers. (Looking Lilian over) Size five and a half by one and a quarter—hurry, old ‘un, fly.

Susie. Whatever do he mean?

Lilian. He only means that he wants a taxi.

Susie. Oh, that! Mother’s gone out, and you know what father is, sir, but I’ll get it myself.

Hugh. No, you don’t, Susie, not in the rain. Back in a jiffy, Lilian.

(He is gone, and they hear his boisterous leap of the ladder.)

Susie. He is just bubbling over, and all because he is going off to make dams.

Lilian (asking too much). Has he been bubbling over for long, Susie?

Susie (innocently giving it). For days and days. I used to think of him out in Egypt in a very dirty state till I saw a picture of him, all in laundry white, and riding on a camel.

Lilian. The camel goes on its knees to him, Susie.

Susie (heartily). I don’t wonder at it. (She is on her own knees giving those finishing touches to the baggage which she knows can only come from a woman’s hands.) There was a thing about him in the paper, and it said ‘The ball is at his feet.’

Lilian. And it is. A great career.

Susie (looking sometimes six and sometimes sixty). For him. But I have just to make ready for another lodger. That is all the great career there is for the likes of me. (Wistfully) I’m thinking there is a great career for you.

Lilian (smiling). How, Susie?

Susie. Him. (She rises.) I wonder would you let me see it. I have never seen them except in shop windows.

Lilian. What?

Susie. Fine you know. The thing that is on the third finger of your left hand.

Lilian (showing a bare finger). Nothing, you see.

Susie (sharp). You haven’t landed him yet?

(She is so disappointed that Lilian is kind.)

Lilian. All is lovely, Susie.

Susie (who must have it plainer than that). You’ve got him?

Lilian. I’ve got him.

Susie. Lucky you!

Lilian. Yes, lucky me. You mustn’t grudge him to me, Susie. I haven’t always been lucky with men.

Susie. Men—oh, men! Most men deserves all they gets. (She screws up her eyes and opens them to explain.) I was just seeing you and him on your camels.

(There is a knocking on the outer door.)

Lilian. There he is.

Susie. I haven’t got back his key. (She knows the familiar sounds of the mews.) It’s not him. There is something wrong.

Lilian. Quick, Susie.

(The child is gone for a moment, and Lilian is conscious of some disturbance in the passage below.)

Susie (reappearing, terrified). Oh, miss!

Lilian. Tell me.

Susie. They are carrying him into his bedroom.

Lilian. Not Mr. Paton? Speak!

Susie. It’s him! He was run over.

(She disappears again, but the tramp of feet is heard through the open door. A grave man comes up the ladder. He is wearing an overcoat and muffler and he closes the door.)

Dr. Brodie. Poor lady! I suppose you——

Lilian. Tell me!

Dr. Brodie. He was run over by a motor bus. It is very serious.

Lilian. Tell me!

Dr. Brodie. I must tell you. He is dead.

Lilian. No, he isn’t.

Dr. Brodie. He died as they picked him up.

Lilian. It isn’t true.

Dr. Brodie. A Mr. Paton, they tell me. I don’t know him. I am a doctor and I happened to be passing. He only spoke one word.

Lilian. My name?

Dr. Brodie. The word was Egypt.

Lilian. He is going there. He had gone out for a taxi. So you see it can’t be true.

Dr. Brodie. It is true, alas. (He gets her into a chair.) Mrs. Paton, I want to help you in any way possible. There seems to be no one in the house but a very useless man and a child. If you can give me the address of any male relative——

Lilian (starting up.) You mustn’t bring anyone here.

Dr. Brodie. Just to help you with—I don’t quite—Excuse me, are you Mrs. Paton? (The pitiful look she gives him makes him avert his troubled eyes.) I am sure you will understand that I have no wish to intrude. But someone must communicate with the relatives. And of course an inquiry——

Lilian. You mean, I have no right to be here?

Dr. Brodie. I don’t know whether you have a right or not. But you must know. (As she shrinks from him) Pardon me, I won’t disturb you any longer.

Lilian. Don’t go. What am I to do?

Dr. Brodie. If it is well for him to have it publicly known that you were here you will of course remain; but if it would not be well for him, my advice to you—as you ask for it, unhappy lady, is to go at once.

Lilian (throwing out her arms). Where am I to go?

Dr. Brodie. I know nothing of the circumstances. I am only telling you what I think might be best for him.

Lilian (dry-eyed). Is there to be no thought of what would be best for me?

Dr. Brodie (gently). Might it not be best for you also?

Lilian. I have nowhere to go—nowhere.

(Perhaps he does not quite believe her, but if his manner hardens it is only to gain his point.)

Dr. Brodie. Better that I should know nothing.

Lilian. I am not what you think me.

Dr. Brodie. No one is. But prove it, madam, by going.

Lilian. What is to become of me? (He shakes his head.) I loved him—I risked everything for him—I am lost.

Dr. Brodie. Those who risk all and lose have to face the consequences.

Lilian. I was going with him.

(He might say, “You can go with him still, unfortunate one, if you choose,” but of course he does not. Instead he opens the door respectfully. She bows, gives him a pitiful smile of thanks and goes away.

Let us return to Garson’s house and see how his little dinner is faring.

As Mr. Garson enters the room in evening dress, his bad temper removed with his clothes, he meets his butler.)

Garson. Have I time to write a note, Withers?

Withers. It is two minutes short of the half-hour, sir.

Garson (going to his desk). Her ladyship not down yet?

Withers. I believe not, sir.

Garson. She isn’t usually late. I didn’t hear her in her room.

Withers. Shall I send up to inquire, sir?

Garson. Oh, no, she will be down directly, no doubt.

(He sits at a desk and unlocks a drawer with his keys. It is the fatal drawer. Stretching out his hand for some papers he knows to be there, it encounters something metallic, which he draws out. Without rising he feels for further jewellery, but there is evidently no more. He has recognised his find but has no suspicions, and is sitting there chuckling over it when Withers announces two guests, Mr. and Mrs. Redding, both exuding opulence.)

Redding. You seem to be having a little joke all to yourself, Garson.

Garson. Ah, welcome both.

Mrs. Redding. But the joke?

(For reply their host holds up the jewels.)

Redding. My eye! No joke for the party that footed the bill.

Garson. I put my hand into that drawer for some papers, and it found these instead.

Redding. All I can say is “Halves.”

Mrs. Redding. Silly man, they are Lady Lilian’s. I know them quite well.

Garson. The joke, Redding, is that I now see why my wife is late for dinner.

Mrs. Redding. It is we who are early; but tell us.

Garson. She must have shoved them in there—(with a certain pride) her set are more careless than ours—and then forgotten where she put them. I bet she is searching high and low for them at this moment.

Mrs. Redding (who would like to say that her set can be fashionably careless also). The poor dear! But suppose some servant, the awful man who winds the clocks——

Garson. Oh, they were safe enough. She had happened to find the drawer unlocked but she had the sense to shut it, and all these drawers lock when they shut. (He shuts the drawer and it clicks, perhaps an effort to tell its master something.) I have the only key. (He puts the jewels into his pocket and greets another guest.)

Withers. Dr. Brodie.

Garson. Very pleased to see you, Brodie, in my little place.

Dr. Brodie. Thank you, Garson. (He presumes that Mrs. Redding is his hostess) Lady Lilian, I am——

Garson. No, no, that isn’t Lady Lilian.

Mrs. Redding (archly). Would that it were, Dr. Brodie!

Redding (equally ready). Oh, come!

Garson. Dr. Brodie—Mrs. Redding. You have met at the club, Redding.

Redding. To be sure.

Garson. I forgot you don’t know my wife, Brodie. She will be down in a moment. I must apologise for her being late.

Mrs. Redding. Don’t fuss, Mr. Garson. Dr. Brodie knows what women are.

Dr. Brodie. Not I, Mrs. Redding. But I was afraid I should be late myself.

Redding. Something professional?

Dr. Brodie. Accident in the street. Man knocked over by a motor bus—killed.

Garson. Rough luck. I can’t think what is keeping Lady Lilian.

Redding. Someone you knew, doctor?

Dr. Brodie. No, but he seems to have done good work in India. Paton is the name.

Garson. Paton? There was a Paton we met once at dinner who—no, Egypt was his place.

Dr. Brodie. It was Egypt she said. Probably your man.

Mrs. Redding. Was he married?

Dr. Brodie. No, not married. (He sighs.) Poor devil!

Redding. Surely better in the circumstances that he wasn’t married.

Dr. Brodie. Oh, much better.

Mrs. Redding. You said “poor devil.”

Dr. Brodie. Did I? I was thinking of something else.

Mrs. Redding. Of the lady?

Dr. Brodie (not delighting in her). Did I say there was a lady?

Mrs. Redding (smartly). You are saying it now.

Redding. Got you, my friend!

Dr. Brodie. Hm! (His desire is to drop the subject.) Beast of a night, Garson.

Garson. Wet?

Dr. Brodie. Drizzle. The most dismal sort of London night.

Mrs. Redding. And the poor devil is out in it?

Dr. Brodie. She is out in it, right enough.

(Lady Lilian is not, however, out in it. She now sweeps in from upstairs in a delicious evening confection. She must have dressed in record time, for no doubt she lost a moment trying to open that drawer. She must even have raced her brain, which may be conceived by the fanciful as descending the stairs in pursuit of her.)

Garson. You are terribly late, Lilian.

(She knows at once that nothing has been discovered as yet, and her wits make up on her.)

Lilian. Dear Mrs. Redding, I am so ashamed. Forgive me, kind Mr. Redding.

Redding (a courtier when approached infantilely). All I can say, Lady Lilian, is that you were worth waiting for.

(Then she sees the doctor, and the recognition is mutual.)

Garson. Brodie, my wife at last. I forget, Lilian, whether I mentioned that Dr. Brodie had kindly promised to take pot-luck with us.

Lilian. No, but I am so pleased, Dr. Brodie—any friend of my husband.

Dr. Brodie. Thank you, Lady Lilian.

Mrs. Redding. He has been telling us such a shocking story.

Redding. It will spoil my dinner.

Garson. Not quite, I hope, Redding.

Redding. No, not quite.

(They have both a gift for this sort of talk, and have sunny times together.)

Mrs. Redding. A man killed in the street. Tell her, Dr. Brodie.

Dr. Brodie. It wouldn’t interest Lady Lilian.

Garson. Yes, by the way it would. You will remember him, Lil.

Lilian. Someone I know?

Garson. Paton is the name. I think it was at the Rossiters’ we met him.

Lilian. A barrister?

Garson. No, an engineer—abroad—in a small way.

Lilian. A dark man, wasn’t he?

Dr. Brodie. No, fair. Evidently if you ever knew him, Lady Lilian, you have forgotten him.

Lilian. One meets so many.

Dr. Brodie. Just so.

Mrs. Redding. There was a woman in it, Lady Lilian. Do get him to tell us.

Lilian (boldly). Why not?

Dr. Brodie. Very well. I assure you I pitied her when I thought she was his wife, and still more when I found she wasn’t.

Garson. That sort of woman!

Lilian. What sort of woman, Richard?

Garson (with delicacy). Oh, come!

Dr. Brodie. She kept crying, what could she do.

Garson. She knew what she could do!

Lilian. What could she do, Richard?

Garson. Pooh! They don’t all get run over by motor buses, my dear.

Dr. Brodie. I thought she might find a job—women do nowadays—and live on, true to the dead. After all, it was the test of her.

Lilian. I suppose it was.

Garson. What a sentimental fellow you are, Brodie! That kind can look after themselves all right. I say, Redding, suppose she is a married woman and has bolted back to unsuspecting No. 1!

Redding. Lordy!

Dr. Brodie. When she left the house at my request I couldn’t have thought so despicably of her as that.

Lilian. Is it more abject than my husband’s other end for her?

Dr. Brodie. I should say, yes.

Redding. It’s quite possible, you know, Garson. Makes a pretty chump of the husband, though.

Garson. No doubt. And yet there is humour in it. You don’t see, Brodie, that it has its humorous side?

Dr. Brodie. Oh, yes, I do, Garson. But as I walked here I was picturing her in dire desolation.

Lilian. Don’t you think she may be in dire desolation still?

Dr. Brodie. Thinking it over, Lady Lilian, I have come to the conclusion that your husband is right, and that I was a sentimental fellow, wasting my sympathy on that lady.

Garson (who is not unsusceptible to praise). Exactly.

(Dinner is announced, and he is indicating to Brodie to take in Lady Lilian, when Mrs. Redding, the only one who has remembered the jewellery, touches her throat and wrists significantly. He gives her and her husband a private wink.)

Hullo, Lil, where are those emeralds? Didn’t you get ’em out of me specially for that frock?

(Only one of the company, a new acquaintance, notices his hostess go rigid for a moment. So her husband has found the jewels! Something inside her that is clamouring for utterance is about to betray her, when she sees a glance pass from her husband to the drawer. She is uncertain how much has been found out, but she cannot believe that if this man knows everything he could have had the self-control to play cat to her for so long.)

Lilian (taking a risk). I took them off down here and left them for safety in one of your drawers.

Garson. Which drawer?

Lilian (crossing to it). This one.

Garson (making a sign with his fingers behind his back to the Reddings). Best put them on; I like you in ’em.

(He tosses her his keys, and as she opens the drawer he has another gleeful moment with his accomplices. Brodie, whose attention is confined to her, understands that somehow a crisis has been reached, and oddly enough he does not want her to be caught.)

Lilian (turning round, aghast). They are gone!

Garson (histrionically). Gone?

Lilian. Richard, what is to be done? My emeralds!

Garson. Gone! The police——

Lilian. Yes, yes!

Mrs. Redding. Mr. Garson, how can you keep it up? Don’t you see she is nearly fainting, and so should I be. Emeralds!

Garson (with the conqueror’s good nature). Come, come, Lil, calm yourself. This should be a lesson to you, though. But it’s all right—just a trick I was playing on you. I found them in the drawer.

Redding (admiringly). Never was such a masterpiece at a trick as Garson!

Garson (producing the jewels from his pocket like a wizard). Here they are!

(He gallantly places them on her person, and even gives her a peck, which brings him very near to something she is holding in her hand beneath her handkerchief. Garson takes in Mrs. Redding, and Redding has to go without a lady. Before Lilian and Brodie follow them she throws a letter into the fire, and as the little spitfire turns to ashes she puts on her finger a wedding-ring that she has taken out of it. She reels for a moment, then looks to Brodie for his commentary. He has none, but as a medical man he feels her pulse.)