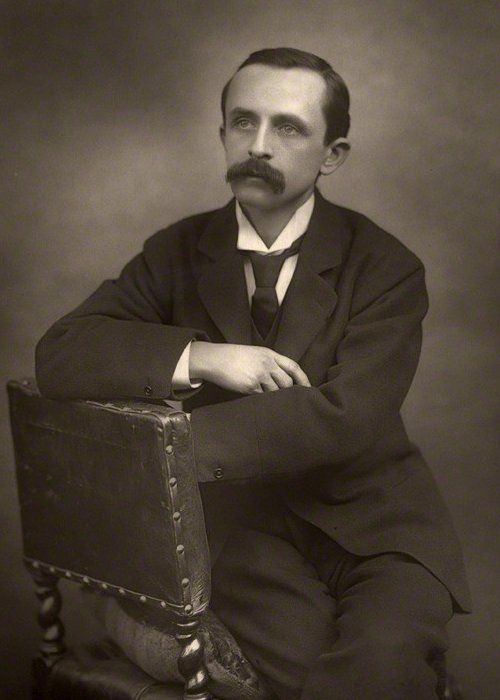

Shall We Join the Ladies? Play by James Matthew Barrie

SHALL WE JOIN THE LADIES? PLAY

For the past week the hospitable Sam Smith has been entertaining a country house party, and we choose to raise the curtain on them towards the end of dinner. They are seated thus, the host facing us:

| Host (Mr. Dion Boucicault) |

||

| Lady Jane (Miss Fay Compton) |

Lady Wrathie (Miss Sybil Thorndike) |

|

| Sir Joseph (Mr. Cyril Maude) |

Mr. Preen (Sir Charles Hawtrey) |

|

| Mrs. Preen (Lady Tree) |

O |

Miss Vaile (Miss Marie Lohr) |

| Mr. Vaile (Mr. Nelson Keys) |

Mrs. Bland (Miss Madge Titheradge) |

|

| Mr. Gourlay (Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson) |

Capt. Jennings Mr. Leon Quartermaine) Miss Isit (Miss Irene Vanbrugh) |

|

| Mrs. Castro (Miss Lillah McCarthy) |

||

| Butler (Sir Gerald du Maurier) |

||

| Maid (Miss Hilda Trevelyan) |

This is the first act of an unfinished play originally produced at the opening of the Royal Dramatic Academy’s Theatre, which accounts for the brilliancy of the cast, and the brilliancy of the cast excuses the proud author for giving it in full.

Smith is a little old bachelor, and sits there beaming on his guests like an elderly cupid. So they think him, but they are to be undeceived. Though many of them have not met until this week, they have at present that genial regard for each other which steals so becomingly over really nice people who have eaten too much.

Dolphin, the butler, is passing round the fruit. The only other attendant is a maid in the background, as for an emergency, and she is as interested in the conversation as he is indifferent to it. If one of the guests were to destroy himself, Dolphin would merely sign to her to remove the debris while he continued to serve the fruit.

In the midst of hilarity over some quip that we are just too late to catch, the youthful Lady Jane counts the company and is appalled.

Lady Jane. We are thirteen, Lady Wrathie.

(Many fingers count.)

Lady Wrathie. Fourteen.

Capt. Jennings. Twelve.

Lady Jane. We are thirteen.

Host. Oh dear, how careless of me. Is there anything I can do?

Sir Joseph (of the city). Leave this to me. All keep your seats.

Mrs. Preen (perhaps rather thankfully). I am afraid Lady Jane has risen.

(Lady Jane subsides.)

Lady Wrathie. Joseph, you have risen yourself.

(Sir Joseph subsides.)

Mrs. Castro (a mysterious widow from Buenos Ayres). Were we thirteen all those other nights?

Mrs. Preen. We always had a guest or two from outside, you remember.

Miss Isit (whose name obviously needs to be queried). All we have got to do is to make our number fourteen.

Vaile. But how, Miss Isit?

Miss Isit. Why, Dolphin, of course.

Mrs. Preen. It’s too clever of you, Miss Isit. Mr. Smith, Dolphin may sit down with us, mayn’t he?

Mrs. Castro. Please, dear Mr. Smith; just for a moment. That breaks the spell.

Sir Joseph. We won’t eat you, Dolphin. (But he has crunched some similar ones.)

Host. Let me explain to him. You see, Dolphin, there is a superstition that if thirteen people sit down at table something staggering will happen to one of them before the night is out. That is it, isn’t it?

Mrs. Bland (darkly). Namely, death.

Host (brightly). Yes, namely, death.

Lady Jane. But not before the night is out, you dear; before the year is out.

Host. I thought it was before the night is out.

(Dolphin is reluctant.)

Gourlay. Sit here, Dolphin.

Miss Vaile. No, I want him.

Miss Isit. It was my idea, and I insist on having him.

Mrs. Castro (moving farther to the left). Yes, here between us.

(Dolphin obliges.)

Mrs. Preen (with childish abandon). Saved.

Host. As we are saved, and he does not seem happy, may he resume his duties?

Lady Wrathie. Yes, yes; and now we ladies may withdraw.

Preen (the most selfish of the company, and therefore perhaps the favourite). First, a glass of wine with you, Dolphin.

Vaile (ever seeking to undermine Preen’s popularity). Is this wise?

Preen (determined to carry the thing through despite this fellow). To the health of our friend Dolphin.

(Dolphin’s health having been drunk, he withdraws his chair and returns to the sideboard. As Miss Isit and Mrs. Castro had made room for him between them exactly opposite his master, and the space remains empty, we have now a better view of the company. Can this have been the author’s object?)

Sir Joseph (pleasantly detaining the ladies). One moment. Another toast. Fellow-guests, to-morrow morning, alas, this party has to break up, and I am sure you will all agree with me that we have had a delightful week. It has not been an eventful week; it has been too happy for that.

Capt. Jennings. I rise to protest. When I came here a week ago I had never met Lady Jane. Now, as you know, we are engaged. I certainly call it an eventful week.

Lady Jane. Yes, please, Sir Joseph.

Sir Joseph. I stand corrected. And now we are in the last evening of it; we are drawing nigh to the end of a perfect day.

Preen (who is also an orator). In seconding this motion——

Vaile. Pooh. (He is the perfect little gentleman, if socks and spats can do it.)

Sir Joseph. Though I have known you intimately for but a short time, I already find it impossible to call you anything but Sam Smith.

Mrs. Castro. In our hearts, Mr. Smith, that is what we ladies call you also.

Preen. If I might say a word——

Vaile. Tuts.

Sir Joseph. Ladies and gentlemen, is he not like a pocket edition of Mr. Pickwick?

Gourlay (an artist). Exactly. That is how I should like to paint him.

Mrs. Blank. Mr. Smith, you love, we think that if you were married you could not be quite so nice.

Sir Joseph. At any rate, he could not be quite so simple. For you are a very simple soul, Sam Smith. Well, we esteem you the more for your simplicity. Friends all, I give you the toast of Sam Smith.

(The toast is drunk with acclamation, and Dolphin, who has paid no attention to it, again hovers round with wine.)

Host (rising in answer to their appeals and warming them with his Pickwickian smile). Ladies and gentlemen, you are very kind, and I don’t pretend that it isn’t pleasant to me to be praised. Tell me, have you ever wondered why I invited you here?

Miss Isit. Because you like us, of course, you muddle-headed darling.

Host. Was that the reason?

Sir Joseph. Take care, Sammy, you are not saying what you mean.

Host. Am I not? Kindly excuse. I dare say I am as simple as Sir Joseph says. And yet, do you really know me? Does any person ever know another absolutely? Has not the simplest of us a secret drawer inside him with—with a lock to it?

Miss Isit. If you have, Mr. Smith, be a dear and open it to us.

Mrs. Castro. How delicious. He is going to tell us of his first and only love.

Host. Ah, Mrs. Castro, I think I had one once, very nice, but I have forgotten her name. The person I loved best was my brother.

Preen. I never knew you had a brother.

Host. I suppose none of you knew. He died two years ago.

Sir Joseph. Sorry, Sam Smith.

Mrs. Preen (drawing the chocolates nearer her). We should like to hear about him if it isn’t too sad.

Host. Would you? He was many years my junior, and as attractive as I am commonplace. He died in a foreign land. Natural causes were certified. But there were suspicious circumstances, and I went out there determined to probe the matter to the full. I did, too.

Preen. You didn’t say where the place was.

Host. It was Monte Carlo.

(He pauses here, as if to give time for something to happen, but nothing does happen except that Miss Isit’s wine-glass slips from her hand to the floor.)

Dolphin, another glass for Miss Isit.

Lady Jane. Do go on.

Host. My inquiries were slow, but I became convinced that my brother had been poisoned.

Mrs. Bland. How dreadful. You poor man.

Gourlay. I hope, Sam Smith, that you got on the track of the criminals?

Host. Oh, yes.

(A chair creaks.)

Did you speak, Miss Isit?

Miss Isit. Did I? I think not. What did you say about the criminals?

Host. Not criminals; there was only one.

Preen. Man or woman?

Host. We are not yet certain. What we do know is that my brother was visited in his rooms that night by someone who must have been the murderer. It was someone who spoke English and who was certainly dressed as a man, but it may have been a woman. There is proof that it was someone who had been to the tables that night. I got in touch with every “possible,” though I had to follow some of them to distant parts.

Lady Wrathie. It is extraordinarily interesting.

Host. Outwardly many of them seemed to be quite respectable people.

Sir Joseph. Ah, one can’t go by that, Sam Smith.

Host. I didn’t. I made the most exhaustive inquiries into their private lives. I did it so cunningly that not one of them suspected why I was so anxious to make his or her acquaintance; and then, when I was ready for them, I invited them to my house for a week, and they are all sitting round my table this evening.

(As the monstrous significance of this sinks into them, there is a hubbub at the table.)

You wanted to know why I had asked you here, and I am afraid that in consequence I have wandered a little from the toast; but I thank you, Sir Joseph, I thank you all, for the too kind way in which you have drunk my health.

(He sits down as modestly as he had risen, but the smile has gone from his face; and the curious—which includes all the diners—may note that he is licking his lips. In the babel that again breaks forth, Dolphin, who has remained stationary and vacuous for the speech, goes the round of the table refilling glasses.)

Preen (the first to be wholly articulate). In the name of every one of us, Mr. Smith, I tell you that this is an outrage.

Host. I was afraid you wouldn’t like it.

Sir Joseph. May I ask, sir, whether all this week you have been surreptitiously ferreting into our private affairs, perhaps even rummaging our trunks?

Host (brightening). That was it. You remember how I pressed you all to show your prowess on the tennis courts and the golf links while I stayed at home? That was my time for the trunks.

Lady Jane. Was there ever such a man? Did you open our letters?

Host. Every one of them. And there were some very queer things in them. There was one about a luncheon at the Ritz. “You will know me,” the man wrote, “by the gardenia I shall carry in my hand.” Perhaps I shouldn’t have mentioned that. But the lady who got that letter need not be frightened. She is married, and her husband is here with her, but I won’t tell you any more.

Miss Isit. I think he should be compelled to tell.

Preen. Wrathie, there are only two ladies here with their husbands.

Sir Joseph. Yours and mine, Preen.

Lady Wrathie. Joseph, I don’t need to tell you it wasn’t your wife.

Mrs. Preen. It certainly wasn’t yours, Willie.

Preen. Of that I am well assured.

Sir Joseph. Take care what you say, Preen. That is very like a reflection on my wife.

Gourlay. Let that pass. The other is the serious thing—so serious that it is a nightmare. Whom do you accuse of doing away with your brother, sir? Out with it.

Host. You are not all turning against me, are you? I assure you I don’t accuse any of you yet. I know that one of you did it, but I am not sure which one. I shall know soon.

Vaile. Soon? How soon?

Host. Soon after the men join the ladies to-night. I ought to tell you that I am to try a little experiment to-night, something I have thought out which I have every confidence will make the guilty person fall into my hands like a ripe plum. (He indicates rather horribly how he will squeeze it.)

Lady Jane (hitting his hand). Don’t do that.

Sir Joseph (voicing the general unrest). We insist, Smith, on hearing what this experiment is to be.

Host. That would spoil it. But I can tell you this. My speech had a little pit in it, and all the time I was talking I was watching whether any of you would fall into that pit.

Mrs. Preen (rising). I didn’t notice any pit.

Host. You weren’t meant to, Mrs. Preen.

Preen. May I ask, without pressing the personal note, did any one fall into your pit?

Host. I think so.

Capt. Jennings. Smith, we must have the name of this person.

Lady Wrathie. Mrs. Preen has fainted.

(Preen hurries slowly to his wife’s assistance, and there is some commotion.)

Mrs. Preen. Why—what—who—I am all right now. Willie, go back to your seat. Why are you all staring at me so?

Miss Isit. Dear Mrs. Preen, we are so glad that you are better. I wonder what upset you?

Preen (imprudently). I never knew her faint before.

Miss Isit. I expect it was the heat.

Preen (nervous). Say it was the heat, Emily.

Mrs. Preen. No, it wasn’t the heat, Miss Isit. It was Mr. Smith’s talk of a pit.

Preen. My dear.

Mrs. Preen. I suddenly remembered how, as soon as that man mentioned that the place of the crime was Monte Carlo, some lady had let her wine-glass fall. That was why I fainted. I can’t remember who she was.

Lady Wrathie. It was Miss Isit.

Mrs. Preen. Really?

Miss Isit. There is a thing called the law of libel. If Lady Wrathie and Mrs. Preen will kindly formulate their charges——

Gourlay. Oh, come, let us keep our heads.

Host. That’s what I say.

Gourlay. What about a motive? Scotland Yard always seeks for that first.

Host. I see two possible motives. If a woman did it—well, they tended to run after my brother, and you all know of what a woman scorned is capable.

Preen (reminiscent). Rather.

Host. Then, again, my brother had a large sum of money with him, which disappeared.

Sir Joseph. If you could trace that money it might be a help.

Host. All sorts of things are a help. The way you are all pretending to know nothing about the matter is a help. It might be a help if I could find out which of you has a clammy hand that at this moment wants to creep beneath the table.

(Not a hand creeps.)

I’ll tell you something more. Murderers’ hearts beat differently from other hearts. (He raises his finger.) Listen.

(They listen.)

Whose was it?

(A cry from Miss Vaile brings her into undesired prominence.)

Miss Vaile (explaining). I thought I heard it. It seemed to come from across the table.

(This does not give universal satisfaction.)

Please don’t think because this man made me scream that I did it. I never was on a yacht in my life, at Monte Carlo or anywhere else.

(Nor does even this have the desired effect.)

Vaile (sharply). Bella!

Miss Vaile. Have I said—anything odd?

Gourlay. A yacht? There has been no talk about a yacht.

Miss Vaile (shrinking). Hasn’t there?

Host. Perhaps there should have been. It was on his yacht that my brother died.

Mrs. Castro. You said in his rooms.

Host. Yes, that is what I said. I wanted to find out which of you knew better.

Lady Jane. And Miss Vaile——

Miss Vaile. I can explain it all if—if——

Miss Isit. Yes, give her a little time.

Host. Perhaps you would all like to take a few minutes.

Miss Vaile. I admit that I was at Monte Carlo—with my brother—when an Englishman died there rather mysteriously on a yacht. When Mr. Smith told us of his brother’s death, I concluded that it was probably the same person.

Vaile. I presume that you accept my sister’s statement?

Miss Isit. Ab-sol-ute-ly.

Host. She is not the only one of you who knew that yacht. You all admit having been at Monte Carlo two years ago, I suppose?

Capt. Jennings. One of us wasn’t. Lady Jane was never there.

Host (with beady eyes). What do you say to that, Lady Jane?

(Lady Jane falters.)

Capt. Jennings. Tell him, Jane.

Host. Yes, tell me.

Capt. Jennings. You never were there; say so.

Lady Jane. Why shouldn’t I have been there?

Capt. Jennings. No reason. But when I happened to mention Monte Carlo to you the other day I certainly understood—— Jane, I never forget a word you say, and you did say you had never been there.

Lady Jane. So you—you, Jack—you accuse me—you—me——

Capt. Jennings. I haven’t, I haven’t.

Lady Jane. You have all heard that Captain Jennings and I are engaged. I want you to understand that we are so no longer.

Capt. Jennings. Jane!

(She removes the engagement ring from her finger and hesitates how to transfer it to the donor, who is many seats apart from her. The ever-resourceful Dolphin goes to her with a tray on which she deposits the ring, and it is thus conveyed to the unhappy Jennings. Next moment Dolphin has to attend to the maid, who makes an audible gurgle of sympathy with love, which is a breach of etiquette. He opens the door for her, and she makes a shameful exit. He then fills the Captain’s glass.)

Host (in one of his nicer moods). Take comfort, Captain. If Lady Jane should prove to be the person wanted—mind you, perhaps she isn’t—why, then the ring is a matter of small importance, because you would be parted in any case. I mean by the handcuffs. I forgot to say that I have them here. (He gropes at his feet, where other people merely have a table-napkin.) Pass them round, Dolphin. Perhaps some of you have never seen them before.

Preen. A pocket edition of Pickwick we called him; he is more like a pocket edition of the devil.

Host. Please, a little courtesy. After all, I am your host.

(Dolphin goes the round of the table with the handcuffs on the tray that a moment ago contained a lover’s ring. They meet with no success.)

Do take a look at them, Mrs. Castro; they are an adjustable pair in case they should be needed for small wrists. Would you like to try them on, Sir Joseph? They close with a click—a click.

Sir Joseph (pettishly). We quite understand.

(Mrs. Bland rises.)

Mrs. Bland. How stupid of us. We have all forgotten that he said the murderer may have been a woman in man’s clothes, and I have just remembered that when we played the charade on Wednesday he wanted the ladies to dress up as men. Was it to see whether one of us looked as if she could have passed for a man that night at Monte Carlo?

Host. You’ve got it, Mrs. Bland.

Sir Joseph. Well, none of you did dress up, at any rate.

Mrs. Bland (distressed). Oh, Sir Joseph. Some of us did dress up, in private, and we all agreed that—of course there’s nothing in it, but we all agreed that the only figure which might have deceived a careless eye was Lady Wrathie’s.

Preen. I say!

Lady Wrathie. Joseph, do you sit there and permit this?

Host. Now, now, there is nothing to be touchy about. Have I not been considerate?

Sir Joseph. Smith, I hold you to be an impudent scoundrel.

Host. May not I, who lost a brother in circumstances so painful, appeal for a little kindly consideration from those of you who are innocent—shady characters though you be?

Preen. I must say that rather touches me. Some of us might have reasons for being reluctant to have our past at Monte inquired into without being the person you are asking for.

Host. Precisely. I am presuming that to be the position of eleven of you.

Lady Wrathie. Joseph, I must ask you to come upstairs with me to pack our things.

Miss Isit. For my part, after poor Mr. Smith’s appeal I think it would be rather heartless not to stay and see the thing out. Especially, Mr. Smith, if you would give us just an inkling of what your—little experiment—in the drawing-room—is to be?

Host. I can’t say anything about it except that it isn’t to take place in the drawing-room. You ladies are to go this evening to Dolphin’s room, where we shall join you presently.

(Even Dolphin is taken aback.)

Mrs. Preen. Why should we go there?

Host. Because I tell you to, Mrs. Preen.

Lady Wrathie. I go to no such room. I leave this house at once.

Mrs. Preen. I also.

Lady Jane. All of us. I want to go home.

Lady Wrathie. Joseph, come.

Mrs. Preen. Willie, I am ready. I wish you a long good-bye, Mr. Smith.

(Their dignified advance upon the door is spoilt on opening it by their finding a policeman (Mr. Norman Forbes) standing there. They glare at Mr. Smith.)

Host. The ladies will now adjourn to Dolphin’s room.

Lady Wrathie. I say no.

Mrs. Castro. Let us. Why shouldn’t the innocent ones help him?

(She gives Smith her hand with a disarming smile.)

Host. I knew you would be on my side, Mrs. Castro. Cold hand—warm heart. That is the saying, isn’t it?

(She shrinks.)

Lady Wrathie. Those who wish to leave this man’s house, follow me.

Host (for her special benefit). My brother’s cigarette-case was of faded green leather, and a hole had been burned in the back of it.

(For some reason this takes the fight out of her, and she departs for Dolphin’s room, tossing her head, and followed by the other ladies.)

Vaile (seeing Smith drop a word to Miss Vaile as she goes). What did you say to my sister?

Host. I only said to her that she isn’t your sister. (The last lady to go is Miss Isit.) So you never met my brother, Miss Isit?

Miss Isit. Not that I know of, Mr. Smith.

Host. I have a photograph of him that I should like to show you.

Miss Isit. I don’t care to see it.

Host. You are going to see it. (It is in his pocket, and he suddenly puts it before her eyes.)

Miss Isit (surprised). That is not—— (She checks herself.)

Host. No, that is not my brother. That is someone you have never seen. But how did you know it wasn’t my brother?

(She makes no answer.)

I rather think you knew Dick, Miss Isit.

Miss Isit (dropping him a curtsey). I rather think I did, Mr. Sam. What then?

(She goes impudently. Now that the ladies have left the room, the men don’t quite know what to do except stare at their little host. Decanter in one hand and a box of cigarettes in the other, he toddles down to what would have been the hostess’s chair had there been a hostess.)

Host. Draw up closer, won’t you?

(They don’t want to, but they do, with the exception of Vaile, who is studying a picture very near the door.)

You are not leaving us, Vaile?

Vaile. I thought——

Host (sharply). Sit down.

Vaile. Oh, quite.

Host. You are not drinking anything, Gourlay. Captain, the port is with you.

(The wine revolves, but no one partakes.)

Preen (heavily). Smith, there are a few words that I think it my duty to say. This is a very unusual situation.

Host. Yes. You’ll have a cigarette, Preen?

(The cigarettes are passed round and share the fate of the wine.)

Gourlay. I wonder why Mrs. Bland—she is the only one of them that there seems to be nothing against.

Vaile. A bit fishy, that.

Preen (murmuring). It was rather odd my wife fainting.

Capt. Jennings (who has been a drooping figure since a recent incident). I dare say the ladies are saying the same sort of thing about us. (He lights a cigarette—one of his own. Dolphin is offering them liqueurs.)

Preen (sulkily). No, thanks. (But he takes one.) Smith, I am sure I speak for all of us when I say we would esteem it a favour if you ask Dolphin to withdraw.

Host. He has his duties.

Gourlay (pettishly, to Dolphin). No, thanks. He gets on my nerves. Can nothing disturb this man?

Capt. Jennings (also refusing). No, thanks. Evidently nothing.

Sir Joseph (reverting to a more hopeful subject). Everything seems to point to its being a woman—wouldn’t you say, Smith?

Host. I wouldn’t say everything, Sir Joseph. Dolphin thinks it was a man.

Sir Joseph. One of us here?

(Smith nods, and they survey their friend Dolphin with renewed distaste.)

Gourlay. Did he know your brother?

Host. He was my brother’s servant out there.

Vaile (rising). What? He wasn’t the fellow who——?

Host. Who what, Vaile?

Preen. I say!

Vaile (hotly). What do you say?

Preen. Nothing (doggedly). But I say!

(Though Dolphin is now a centre of interest, no one seems able to address him personally.)

Gourlay. Are we to understand that you have had Dolphin spying on us here?

Host. That was the idea. And he helped me by taking your finger-prints.

Vaile. How can that help?

Host. He sent them to Scotland Yard.

Sir Joseph (vindictively). Oh, he did, did he?

Preen. What shows finger-marks best?

Host. Glass, I believe.

Preen (putting down his glass). Now I see why the Americans went dry.

Sir Joseph. Smith, how can you be sure that Dolphin wasn’t the man himself?

(Mr. Smith makes no answer. Dolphin picks up Sir Joseph’s napkin and returns it to him.)

Preen. Somehow I still cling to the hope that it was a woman.

Vaile. If it is a woman, Smith, what will you do?

Host. She shall hang by the neck until she is dead. You won’t try the benedictine, Vaile?

Vaile. No, thanks.

(The maid returns with coffee, which she presents under Dolphin’s superintendence. Most of them accept. The cups are already full.)

Sir Joseph (in his lighter manner). Did you notice what the ladies are doing in Dolphin’s room, Lucy?

Maid (in a tremble, and wishing she could fly from this house). Yes, Sir Joseph, they are wondering, Sir Joseph, which of you it was that did it.

Preen. How like women!

Gourlay. By the way, Smith, do you know how the poison was administered?

Host. Yes, in coffee. (He is about to help himself.)

Maid. You are to take the yellow cup, sir.

Host. Who said so?

Maid. The lady who poured out this evening, sir.

Preen. Aha, who was she?

Maid. Lady Jane Wraye, sir.

Preen. I don’t like it.

Gourlay. Smith, don’t drink that coffee.

Capt. Jennings (in wrath). Why shouldn’t he drink it?

Gourlay. Well, if it was she—a desperate woman—it was given in coffee the other time, remember. But stop, she wouldn’t be likely to do it in the same way a second time.

Vaile. I’m not so sure. Perhaps she doesn’t suspect that Smith knows how it was given the first time. We didn’t know till the ladies had left the room.

Preen (admiring him at last). I say, Vaile, that’s good.

Capt. Jennings. I have no doubt she merely meant that she had sugared it to his taste.

Vaile (smiling). Sugar!

Preen (pinning his faith to Vaile). Sugar!

Gourlay. Couldn’t we analyse it?

Capt. Jennings (the one who is at present looking most like a murderer). Smith, I insist on your drinking that coffee.

Vaile. Lady Jane! Who would have thought it!

Preen (become a mere echo of Vaile). Lady Jane! Who would have thought it!

Capt. Jennings. Give me the yellow cup. (He drains it to the dregs.)

Sir Joseph. Nobly done, in any case. Look here, Jennings—you are among friends—it hadn’t an odd taste, had it?

Capt. Jennings. Not a bit.

Vaile. He wouldn’t feel the effects yet.

Preen. He wouldn’t feel them yet.

Host. Vaile ought to know.

Preen. Vaile knows.

Sir Joseph. Why ought Vaile to know, Smith?

Host. He used to practise as a doctor.

Sir Joseph. You never mentioned that to me, Vaile.

Vaile. Why should I?

Host. Why should he? He is not allowed to practise now.

(We now see that Vaile has unpleasant teeth.)

Preen. A doctor—poison—ease of access.

(His passion for Vaile is shattered. He gives him back the ring, as Capt. Jennings might say, and wanders the room despondently.)

Sir Joseph. We are where we were again.

(Dolphin escorts out the maid, who is not in a condition to go alone.)

Capt. Jennings. At any rate that fellow has gone.

Gourlay (the first to laugh for some time). Excuse me. I suddenly remembered that Wrathie had called this the end of a perfect day.

Host. It isn’t ended yet.

(Mr. Preen in his wanderings towards the sideboard encounters a very large glass and a small bottle of brandy. He introduces them to each other. He swirls the contents in the glass as if hopeful it may climb the rim and so escape without his having to drink it. This is a trick which has become so common with him that when lost in thought he sometimes goes through the motion though there is no glass in his hand.)

Preen (communing with himself). I feel I am not my old bright self. (Sips.) I can’t believe for a moment that it was my wife. (Sips.) And yet—(sips)—that fainting, you know. (Sips.) I should go away for a bit until it blew over. (Sips.) I don’t think I should ever marry again. (Sips and sips, and becomes perhaps a little more like his old bright self.)

Gourlay. There is something shocking about sitting here, suspecting each other in this way. Let us go to that room and have it out.

Host. I am quite ready. Nothing more to drink, anyone? Bring your cigarette, Captain.

Sir Joseph (hoarsely). Smith—Sam—before we go, can I have a word with you alone?

Host. Sorry, Joseph. And now, shall we join the ladies?

(As they rise, a dreadful scream is heard from the direction of Dolphin’s room—a woman’s scream. Next moment Dolphin reappears in the doorway. He is no longer the imperturbable butler. He is livid. He tries to speak, but no words will come out of his mouth. Capt. Jennings dashes past him, and the others follow. Dolphin looks at his master with mingled horror and appeal, and then goes. Smith sits down again to take one glass of brandy. Where he sits we cannot see his face, but his rigid little back is merciless. As he rises to follow the others the curtain falls on Act One.)