Sanditon by Jane Austen

Sanditon

by

Jane Austen

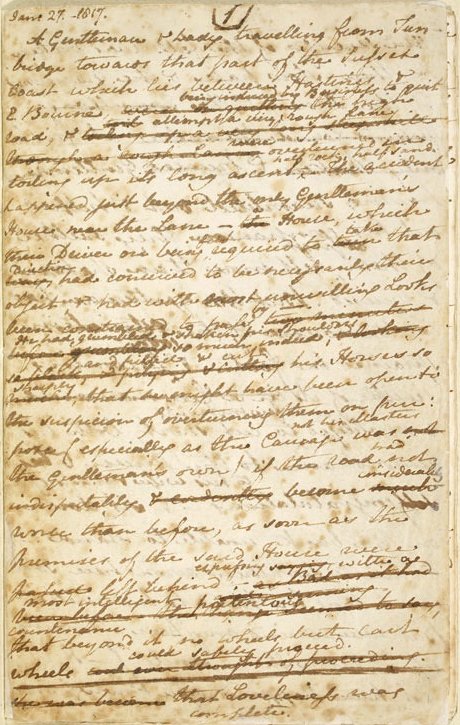

Sanditon (1817) is an unfinished novel by the English writer Jane Austen. In January 1817, Austen began work on a new novel she called The Brothers, later titled Sanditon upon its first publication in 1925, and completed twelve chapters before stopping work in mid-March 1817, probably because her illness prevented her from continuing.

Sanditon Contents

Sanditon Chapter I

Sanditon Chapter II

Sanditon Chapter III

Sanditon Chapter IV

Sanditon Chapter V

Sanditon Chapter VI

Sanditon Chapter VII

Sanditon Chapter VIII

Sanditon Chapter IX

Sanditon Chapter X

Sanditon Chapter XI

Sanditon Chapter XII

Jane Austen Sanditon : Chapter I

A gentleman and a lady travelling from Tunbridge towards that part of the Sussex coast which lies between Hastings and Eastbourne, being induced by business to quit the high road and attempt a very rough lane, were overturned in toiling up its long ascent, half rock, half sand. The accident happened just beyond the only gentleman’s house near the lane—a house which their driver, on being first required to take that direction, had conceived to be necessarily their object and had with most unwilling looks been constrained to pass by. He had grumbled and shaken his shoulders and pitied and cut his horses so sharply that he might have been open to the suspicion of overturning them on purpose (especially as the carriage was not his master’s own) if the road had not indisputably become worse than before, as soon as the premises of the said house were left behind—expressing with a most portentous countenance that, beyond it, no wheels but cart wheels could safely proceed. The severity of the fall was broken by their slow pace and the narrowness of the lane; and the gentleman having scrambled out and helped out his companion, they neither of them at first felt more than shaken and bruised. But the gentleman had, in the course of the extrication, sprained his foot—and soon becoming sensible of it, was obliged in a few moments to cut short both his remonstrances to the driver and his congratulations to his wife and himself—and sit down on the bank, unable to stand.

“There is something wrong here,” said he, putting his hand to his ankle. “But never mind, my dear—” looking up at her with a smile, “it could not have happened, you know, in a better place—Good out of evil. The very thing perhaps to be wished for. We shall soon get relief. There, I fancy, lies my cure—” pointing to the neat-looking end of a cottage, which was seen romantically situated among wood on a high eminence at some little distance—”Does not that promise to be the very place?”

His wife fervently hoped it was; but stood, terrified and anxious, neither able to do or suggest anything, and receiving her first real comfort from the sight of several persons now coming to their assistance. The accident had been discerned from a hayfield adjoining the house they had passed. And the persons who approached were a well-looking, hale, gentlemanlike man, of middle age, the proprietor of the place, who happened to be among his haymakers at the time, and three or four of the ablest of them summoned to attend their master—to say nothing of all the rest of the field—men, women and children, not very far off.

Mr. Heywood, such was the name of the said proprietor, advanced with a very civil salutation, much concern for the accident, some surprise at anybody’s attempting that road in a carriage, and ready offers of assistance. His courtesies were received with good breeding and gratitude, and while one or two of the men lent their help to the driver in getting the carriage upright again, the traveller said, “You are extremely obliging, sir, and I take you at your word. The injury to my leg is, I dare say, very trifling. But it is always best in these cases, you know, to have a surgeon’s opinion without loss of time; and as the road does not seem in a favourable state for my getting up to his house myself, I will thank you to send off one of these good people for the surgeon.”

“The surgeon, sir!” exclaimed Mr. Heywood. “I am afraid you will find no surgeon at hand here, but I dare say we shall do very well without him.”

“Nay sir, if he is not in the way, his partner will do just as well, or rather better. I would rather see his partner. Indeed I would prefer the attendance of his partner. One of these good people can be with him in three minutes, I am sure. I need not ask whether I see the house,” (looking towards the cottage) “for excepting your own, we have passed none in this place which can be the abode of a gentleman.”

Mr. Heywood looked very much astonished, and replied: “What, sir! Are you expecting to find a surgeon in that cottage? We have neither surgeon nor partner in the parish, I assure you.”

“Excuse me, sir,” replied the other. “I am sorry to have the appearance of contradicting you, but from the extent of the parish or some other cause you may not be aware of the fact. Stay. Can I be mistaken in the place? Am I not in Willingden? Is not this Willingden?”

“Yes, sir, this is certainly Willingden.”

“Then, sir, I can bring proof of your having a surgeon in the parish, whether you may know it or not. Here, sir,” (taking out his pocket book) “if you will do me the favor of casting your eye over these advertisements which I cut out myself from the Morning Post and the Kentish Gazette, only yesterday morning in London, I think you will be convinced that I am not speaking at random. You will find in it an advertisement of the dissolution of a partnership in the medical line in your own parish—extensive business, undeniable character respectable references wishing to form a separate establishment. You will find it at full length, sir,”—offering the two little oblong extracts.

“Sir,” said Mr. Heywood with a good humoured smile, “if you were to show me all the newspapers that are printed in one week throughout the kingdom, you would not persuade me of there being a surgeon in Willingden,” said Mr. Heywood with a good-humoured smile. “Having lived here ever since I was born, man and boy fifty-seven years, I think I must have known of such a person. At least I may venture to say that he has not much business. To be sure, if gentlemen were to be often attempting this lane in post-chaises, it might not be a bad speculation for a surgeon to get a house at the top of the hill. But as to that cottage, I can assure you, sir, that it is in fact, in spite of its spruce air at this distance, as indifferent a double tenement as any in the parish, and that my shepherd lives at one end and three old women at the other.”

He took the pieces of paper as he spoke, and, having looked them over, added, “I believe I can explain it, sir. Your mistake is in the place. There are two Willingdens in this country. And your advertisement refers to the other, which is Great Willingden or Willingden Abbots, and lies seven miles off on the other side of Battle—quite down in the Weald. And we, sir,” he added, speaking rather proudly, “are not in the Weald.”

“Not down in the weald, I am sure,” replied the traveller pleasantly. “It took us half an hour to climb your hill. Well, I dare say it is as you say and I have made an abominably stupid blunder—all done in a moment. The advertisements did not catch my eye till the last half hour of our being in town—when everything was in the hurry and confusion which always attend a short stay there. One is never able to complete anything in the way of business, you know, till the carriage is at the door. And, accordingly satisfying myself with a brief inquiry, and finding we were actually to pass within a mile or two of a Willingden, I sought no farther…My dear,” (to his wife) “I am very sorry to have brought you into this scrape. But do not be alarmed about my leg. It gives me no pain while I am quiet. And as soon as these good people have succeeded in setting the carriage to rights and turning the horses round, the best thing we can do will be to measure back our steps into the turnpike road and proceed to Hailsham, and so home, without attempting anything farther. Two hours take us home from Hailsham. And once at home, we have our remedy at hand, you know. A little of our own bracing sea air will soon set me on my feet again. Depend upon it, my dear, it is exactly a case for the sea. Saline air and immersion will be the very thing. My sensations tell me so already.”

In a most friendly manner Mr. Heywood here interposed, entreating them not to think of proceeding till the ankle had been examined and some refreshment taken, and very cordially pressing them to make use of his house for both purposes.

“We are always well stocked,” said he, “with all the common remedies for sprains and bruises. And I will answer for the pleasure it will give my wife and daughters to be of service to you in every way in their power.”

A twinge or two, in trying to move his foot, disposed the traveller to think rather more than he had done at first of the benefit of immediate assistance; and consulting his wife in the few words of “Well, my dear, I believe it will be better for us,” he turned again to Mr. Heywood, and said: “Before we accept your hospitality sir, and in order to do away with any unfavourable impression which the sort of wild-goose chase you find me in may have given rise to, allow me to tell you who we are. My name is Parker, Mr. Parker of Sanditon; this lady, my wife, Mrs. Parker. We are on our road home from London. My name perhaps, though I am by no means the first of my family holding landed property in the parish of Sanditon, may be unknown at this distance from the coast. But Sanditon itself—everybody has heard of Sanditon. The favourite for a young and rising bathing-place, certainly the favourite spot of all that are to be found along the coast of Sussex—the most favoured by nature, and promising to be the most chosen by man.”

“Yes, I have heard of Sanditon,” replied Mr. Heywood. “Every five years, one hears of some new place or other starting up by the sea and growing the fashion. How they can half of them be filled is the wonder! Where people can be found with money and time to go to them! Bad things for a country—sure to raise the price of provisions and make the poor good for nothing—as I dare say you find, sir.”

“Not at all, sir, not at all,” cried Mr. Parker eagerly. “Quite the contrary, I assure you. A common idea, but a mistaken one. It may apply to your large, overgrown places like Brighton or Worthing or Eastbourne but not to a small village like Sanditon, precluded by its size from experiencing any of the evils of civilization. While the growth of the place, the buildings, the nursery grounds, the demand for everything and the sure resort of the very best company whose regular, steady, private families of thorough gentility and character who are a blessing everywhere, excited the industry of the poor and diffuse comfort and improvement among them of every sort. No sir, I assure you, Sanditon is not a place—”

“I do not mean to take exception to any place in particular,” answered Mr. Heywood. “I only think our coast is too full of them altogether. But had we not better try to get you—”

“Our coast too full!” repeated Mr. Parker. “On that point perhaps we may not totally disagree. At least there are enough. Our coast is abundant enough. It demands no more. Everybody’s taste and everybody’s finances may be suited. And those good people who are trying to add to the number are, in my opinion, excessively absurd and must soon find themselves the dupes of their own fallacious calculations. Such a place as Sanditon, sir, I may say was wanted, was called for. Nature had marked it out, had spoken in most intelligible characters. The finest, purest sea breeze on the coast—acknowledged to be so—excellent bathing—fine hard sand—deep water ten yards from the shore—no mud—no weeds—no slimy rocks. Never was there a place more palpably designed by nature for the resort of the invalid—the very spot which thousands seemed in need of! The most desirable distance from London! One complete, measured mile nearer than Eastbourne. Only conceive, sir, the advantage of saving a whole mile in a long journey. But Brinshore, sir, which I dare say you have in your eye—the attempts of two or three speculating people about Brinshore this last year to raise that paltry hamlet lying as it does between a stagnant marsh, a bleak moor and the constant effluvia of a ridge of putrefying seaweed—can end in nothing but their own disappointment. What in the name of common sense is to recommend Brinshore? A most insalubrious air—roads proverbially detestable—water brackish beyond example—impossible to get a good dish of tea within three miles of the place. And as for the soil it is so cold and ungrateful that it can hardly be made to yield a cabbage. Depend upon it, sir, that this is a most faithful Brinshore—not in the smallest degree exaggerated—and if you have heard it differently spoken of—”

“Sir, I never heard it spoken of in my life before,” said Mr. Heywood. “I did not know there was such a place in the world.”

“You did not! There, my dear,” turning with exultation to his wife, “you see how it is. So much for the celebrity of Brinshore! This gentleman did not know there was such a place in the world. Why, in truth, sir, I fancy we may apply to Brinshore that line of the poet Cowper in his description of the religious cottager, as opposed to Voltaire—She, never heard of half a mile from home.”

“With all my heart, sir, apply any verses you like to it. But I want to see something applied to your leg. And I am sure by your lady’s countenance that she is quite of my opinion and thinks it a pity to lose any more time. And here come my girls to speak for themselves and their mother.” (Two or three genteel-looking young women, followed by as many maid servants, were now seen issuing from the house.) “I began to wonder the bustle should not have reached them. A thing of this kind soon makes a stir in a lonely place like ours. Now, sir, let us see how you can be best conveyed into the house.”

The young ladies approached and said everything that was proper to recommend their father’s offers, and in an unaffected manner calculated to make the strangers easy. And, as Mrs. Parker was exceedingly anxious for relief, and her husband by this time not much less disposed for it, a very few civil scruples were enough; especially as the carriage, being now set up, was discovered to have received such injury on the fallen side as to be unfit for present use. Mr. Parker was therefore carried into the house and his carriage wheeled off to a vacant barn.