Under the Sunset and Other Stories by Bram Stoker

Under the Sunset and Other Stories

by

Bram Stoker

Under the Sunset and Other Stories Contents

Under the Sunset

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

The Rose Prince

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

The Invisible Giant

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

The Shadow Builder

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

How 7 Went Mad

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

Lies and Lilies

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

The Castle of the King

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

The Wondrous Child

First published 1881 : Under the Sunset and Other Stories

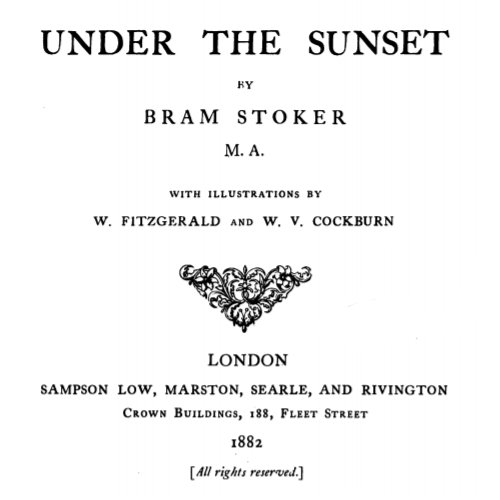

Under the Sunset. By Bram Stoker, MA. With Illustrations by W. Fitzgerald and W. V. Cockburn. London : Sampson Low and Co.

How much do children understand of the fanciful and often beautiful books that are written for their delectation at the present time?

To what extent do they appreciate them?

These are questions which our own experience cannot help us to answer, for, besides that the remembrance of one’s childhood is rarely vivid in these respects, there were no such books in those far past days. After Robinson Crusoe, and the few immortal stories, such as Jack the Giant Killer, Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, and some others which we can all remember, literature for children was poor stuff, mostly consisting of dreadful little moral tales of the Tommy-and-Harry order, relieved only by the ever-glorious exception of Peter Parley’s Annual. That was a book to make one rebel against the ordinance of Nature which decreed that Christmas should come only once a year. What a treat it was, and how we loved it! But even Peter Parley did not appeal to and cultivate the imagination of children as the writers of the present day do. Peter Parley gave only stories of sea and land, of sharks and whales, of deserts and their denizens, of fights and victories, of pleasant school-days, and the peaceful pursuits of home. “P. P.” was great in puzzles, and the farther one was from guessing them, the nicer they were; but in the purely imaginative, he did not deal. Then there was Gammer Grethel, a book for which the world can never be too grateful; but though it was fanciful, inasmuch as it dealt with dwarfs and sprites, wood-goblins, kings, queens, and princesses, it was realistic, too, in the matter-of-fact German way, and put upon the minds of its young readers none of the strain of high sentiment and ingenious allegory.

What a gulf divides the days of Ganuner Grethel, and even those of The Story Without an End (always, we fancy, over the heads of children, unless they were the spectacled sages of German nurseries), and those of Lilliput Levee, Alice in Wonderland, and the beautiful book which lies before us, Under the Sunset, by Mr. Bram Stoker, in whom the children of this year of grace have a new and generous friend! As, however, in that gulf lie buried our own childhood and youth, we ask,— Do the children of this generation appreciate the books that are written for them?

If they do, what a long way ahead of us they must be, at their very first start in reading and thinking life. There is an educational process for the eyes, a refining influence over the taste, in a book like this one, which are not to be lightly estimated, if we are inclined to take anything into consideration with regard to a book for children except whether it will please and amuse them. There is, we think, a test which may be depended upon by which to try the value of a volume of this kind to the little ones. Try it with the big. There are more ardent lovers or frequent quoters of Alice in Wonderland among grown men and women, than among the children to whom the Rabbit and the Jabberwock are quite real and possible; and, indeed, we do not think the humour of the Mock-turtle, or the Walrus and the Carpenter, is to be apprehended of the little people.

Under the Sunset may be tried with the grown-up world with perfect success. To its intellectual and critical perception, the literary charm of the stories—all strung upon a slender, gathering thread, like a pearl necklace or a daisy-chain—will commend themselves highly; while the hearts of the small readers of the chronicles of that beautiful, angel-guarded “Country under the Sunset” will surely respond to the touch of Prince Zaphir and Princess Bluebell.

Here is the introduction to the scene of the poetical and attractive stories which Mr. Bram Stoker tells, with such delightful skill that all children will accept them with entire good-faith, while if we, the wiser and the sadder ones, hear the minor music of them, it will be with no pain :—

“Far, far away there is a beautiful country which no human eye has ever seen in waking hours. Under the sunset it lies, where the distant horizon bounds the day, and where the clouds, splendid with light and colour, give a promise of the glory and beauty which encompass it. Sometimes it is given us to see it in dreams No one can leave the country Under the Sunset except in one direction. Those who go there in dreams, or who come in dreams to our world, come and go they know not how; but if an inhabitant tries to leave it, he cannot, except by one way This place is called the Portal, and there the angels keep guard.”

Pure and beautiful are the beings with whom the Country under the Sunset is peopled, odd and humorous, too; and the tale of their loves and their deeds is in the best style of imaginative narrative, with charming little touches of nature and reference to every-day things, so that the loftiness of its meaning (which is also quite simple) shall not be too sustained a strain upon the small reader, nor his attention be fatigued or puzzled. For instance, there is a delightful passage in the description of the little, motherless prince, Zaphir, about his faithful dog ‘Gomus,’ and about the talk of the angels on guard at the portal. “If we knew the no-language that the Angels were not-speaking, we should have heard thus,” says the author,— and could anything be more happily said in a story of the kind?

The angels, too, are such beautiful creatures in the illustrations to the book, so grand, calm, and powerful, their majestic might reducing the city, with its towers and battlements, its stately castle, and the grand dark portal, to insignificance. Then the giant whom Prince Zaphir slays is such a terrible creature in the story, and in the picture in the latter he resembles the powerful drawing of the monster in La Moison Forestiere, the grimmest conceit of the Erckmann-Charian Romans Populaires. And the old King is so noble and fatherly, the romance of love and war has rarely been so happily blended. In the story of the Prince and the Giant the author uses simple though poetical language; but one word occurs which we had never previously met with. “As the Giant fell, he gave a single cry, but a cry so loud that it rolled away over the hills and valleys like a peal of thunder. At the sound, the living things cowered again, and sagged with fear.” What is “to sag”?

Nothing in this charming book is better than the “knowledgeable” and sympathetic treatment of the “living things.” Animals are the friends and companions of the people in the stories; the small traits of their characters are dexterously indicated, and the sympathy between them and man is brought out with great skill. Mr. Bram Stoker has dedicated his book to his little son. It is well done to set such lessons, such illustrations of the precept,

before the baby mind, that they may sink into the child’s heart, and bear their fruit in the man’s practice. There is strife in these stories, fight for a good cause, sacrifice, bravery, and glory ; but there is not a line to inculcate the love of killing anything made to live by the Creator, or an opportunity lost of drawing out the sympathy of children with the beauty, the intelligence, and the purposes of the animal world. The dogs are very amusing, and admirably differentiated. There is ‘Gomus,’ quite a boy’s dog, who knows when his master is rather solitary in his thoughts, at the hour which is rest-time in the Country under the Sunset, and accordingly wags his tail to say :— “Here I am, prince; I am not asleep, either;” and there is ‘Smog,’ quite a girl’s dog, and ‘Bluebell’s’ property. “This dog,” the author tells us gravely, “was at first called ‘Sumog,’ because Zaphir’s dog was ‘Gomus,’ and this was the name spelled. backwards. But then it was called ‘Smg,’ because this was a name that could not be shouted out, but could only be spoken in a whisper. ‘Bluebell’ had no need for more than this, for ‘Smg’ was never far away, but always stayed close to his mistress, and watched her.”

The illustrations are all real works of art, and one, “The Castle of the King,” in the midst of a great waste, is of very rare beauty, as poetical and as solemn as the story of the poet and his lost love which it illustrates, and which is not, we should think, at all within the reach of childish readers. “The Shadow Builder” is another delicate, refined, and pathetic conceit, touched with a tenderness that never strays into affectation; but happily, the little ones lack the knowledge that will enable its readers of a larger growth to feel its solemn beauty and irresistible truth.

The element of fun, and the pure whimsicality in which Hans Christian Andersen’s stories abound, are abundantly present in Mr. Bram Stoker’s. “How 7 went Mad” might be ranked with the famous “Tin Soldier,” in pleasant unreason; and there is a raven in it—his name is “Mr. Daw “— the honour of whose acquaintance we should greatly like to have. “The Wondrous Child” is what may be called the youngest story in the volume. In its keen sympathy with the fancies, and perception of the absence of proportion in a child’s mind, it is also the cleverest. The volume is beautifully printed, and tastefully bound in white vellum, with red-and-gold lettering and edges; it is, as compared to the children’s books of our time, what the dolls of the period are to the Dutch darlings of the past.

The Spectator

(12th November 1881)