The First Book of Lucan Translated by Christopher Marlowe

THE FIRST BOOK OF LUCAN.

Translated by Christopher Marlowe

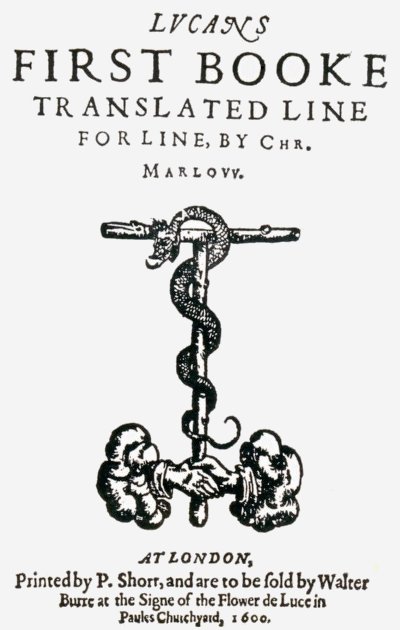

Lucans First Booke Translated Line for Line, By Chr. Marlow. At London, the Flower de Luce in Paules Churchyard, 1600, 4to.

TO HIS KIND AND TRUE FRIEND, EDWARD BLUNT.[576]

Blunt,[577] I propose to be blunt with you, and, out of my dulness, to encounter you with a Dedication in memory of that pure elemental wit, Chr. Marlowe, whose ghost or genius is to be seen walk the Churchyard,[578] in, at the least, three or four sheets. Methinks you should presently look wild now, and grow humorously frantic upon the taste of it. Well, lest you should, let me tell you, this spirit was sometime a familiar of your own, Lucan’s First Book translated; which, in regard of your old right in it, I have raised in the circle of your patronage. But stay now, Edward: if I mistake not, you are to accommodate yourself with some few instructions, touching the property of a patron, that you are not yet possessed of; and to study them for your better grace, as our gallants do fashions. First, you must be proud, and think you have merit enough in you, though you are ne’er so empty; then, when I bring you the book, take physic, and keep state; assign me a time by your man to come again; and, afore the day, be sure to have changed your lodging; in the meantime sleep little, and sweat with the invention of some pitiful dry jest or two, which you may happen to utter with some little, or not at all, marking of your friends, when you have found a place for them to come in at; or, if by chance something has dropped from you worth the taking up, weary all that come to you with the often repetition of it; censure, scornfully enough, and somewhat like a traveller; commend nothing, lest you discredit your (that which you would seem to have) judgment. These things, if you can mould yourself to them, Ned, I make no question that they will not become you. One special virtue in our patrons of these days I have promised myself you shall fit excellently, which is, to give nothing; yes, thy love I will challenge as my peculiar object, both in this, and, I hope, many more succeeding offices. Farewell: I affect not the world should measure my thoughts to thee by a scale of this nature: leave to think good of me when I fall from thee.

Thine in all rights of perfect friendship,

THOMAS THORPE.

FOOTNOTES:

[576] A well-known bookseller.

[577] Old ed. “Blount.”

[578] Paul’s churchyard, the Elizabethan “Booksellers’ Row.”

THE FIRST BOOK OF LUCAN.

Wars worse than civil on Thessalian plains,

And outrage strangling law, and people strong,

We sing, whose conquering swords their own breasts lancht,[579]

Armies allied, the kingdom’s league uprooted,

Th’ affrighted world’s force bent on public spoil,

Trumpets and drums, like[580] deadly, threatening other,

Eagles alike display’d, darts answering darts,

Romans, what madness, what huge lust of war,

Hath made barbarians drunk with Latin blood?

Now Babylon, proud through our spoil, should stoop,

While slaughter’d Crassus’ ghost walks unreveng’d,

Will ye wage war, for which you shall not triumph?

Ay me! O, what a world of land and sea

Might they have won whom civil broils have slain!

As far as Titan springs, where night dims heaven,

I, to the torrid zone where mid-day burns,

And where stiff winter, whom no spring resolves,

Fetters the Euxine Sea with chains of ice;

Scythia and wild Armenia had been yok’d,

And they of Nilus’ mouth, if there live any.

Rome, if thou take delight in impious war,

First conquer all the earth, then turn thy force

Against thyself: as yet thou wants not foes.

That now the walls of houses half-reared totter,

That, rampires fallen down, huge heaps of stone

Lie in our towns, that houses are abandon’d,

And few live that behold their ancient seats;

Italy many years hath lien untill’d

And chok’d with thorns; that greedy earth wants hinds;—

Fierce Pyrrhus, neither thou nor Hannibal

Art cause; no foreign foe could so afflict us:

These plagues arise from wreak of civil power.

But if for Nero, then unborn, the Fates

Would find no other means, and gods not slightly

Purchase immortal thrones, nor Jove joy’d heaven

Until the cruel giants’ war was done;

We plain not, heavens, but gladly bear these evils

For Nero’s sake: Pharsalia groan with slaughter,

And Carthage souls be glutted with our bloods!

At Munda let the dreadful battles join;

Add, Cæsar, to these ills, Perusian famine,

The Mutin toils, the fleet at Luca[s] sunk,

And cruel[581] field near burning Ætna fought!

Yet Rome is much bound to these civil arms,

Which made thee emperor. Thee (seeing thou, being old,

Must shine a star) shall heaven (whom thou lovest)

Receive with shouts; where thou wilt reign as king,

Or mount the Sun’s flame-bearing chariot,

And with bright restless fire compass the earth,

Undaunted though her former guide be chang’d;

Nature and every power shall give thee place,

What god it please thee be, or where to sway.

But neither choose the north t’erect thy seat,

Nor yet the adverse reeking[582] southern pole,

Whence thou shouldst view thy Rome with squinting[583] beams.

If any one part of vast heaven thou swayest,

The burden’d axes[584] with thy force will bend:

The midst is best; that place is pure and bright;

There, Cæsar, mayst thou shine, and no cloud dim thee.

Then men from war shall bide in league and ease,

Peace through the world from Janus’ face shall fly,

And bolt the brazen gates with bars of iron.

Thou, Cæsar, at this instant art my god;

Thee if I invocate, I shall not need

To crave Apollo’s aid or Bacchus’ help;

Thy power inspires the Muse that sings this war.

The causes first I purpose to unfold

Of these garboils,[585] whence springs a long discourse;

And what made madding people shake off peace.

The Fates are envious, high seats[586] quickly perish,

Under great burdens falls are ever grievous;

Rome was so great it could not bear itself.

So when this world’s compounded union breaks,

Time ends, and to old Chaos all things turn,

Confused stars shall meet, celestial fire

Fleet on the floods, the earth shoulder the sea,

Affording it no shore, and Phœbe’s wain

Chase Phœbus, and enrag’d affect his place,

And strive to shine by day and full of strife

Dissolve the engines of the broken world.

All great things crush themselves; such end the gods

Allot the height of honour; men so strong

By land and sea, no foreign force could ruin.

O Rome, thyself art cause of all these evils,

Thyself thus shiver’d out to three men’s shares!

Dire league of partners in a kingdom last not.

O faintly-join’d friends, with ambition blind,

Why join you force to share the world betwixt you?

While th’ earth the sea, and air the earth sustains,

While Titan strives against the world’s swift course,

Or Cynthia, night’s queen, waits upon the day,

Shall never faith be found in fellow kings:

Dominion cannot suffer partnership.

This need[s] no foreign proof nor far-fet[587] story:

Rome’s infant walls were steep’d in brother’s blood;

Nor then was land or sea, to breed such hate;

A town with one poor church set them at odds.[588]

Cæsar’s and Pompey’s jarring love soon ended,

‘Twas peace against their wills; betwixt them both

Stepp’d Crassus in. Even as the slender isthmos,

Betwixt the Ægæan,[589] and the Ionian sea,

Keeps each from other, but being worn away,

They both burst out, and each encounter other;

So whenas Crassus’ wretched death, who stay’d them,

Had fill’d Assyrian Carra’s[590] walls with blood,

His loss made way for Roman outrages.

Parthians, y’afflict us more than ye suppose;

Being conquer’d, we are plagu’d with civil war.

Swords share our empire: Fortune, that made Rome

Govern the earth, the sea, the world itself,

Would not admit two lords; for Julia,

Snatch’d hence by cruel Fates, with ominous howls

Bare down to hell her son, the pledge of peace,

And all bands of that death-presaging alliànce.

Julia, had heaven given thee longer life,

Thou hadst restrain’d thy headstrong husband’s rage,

Yea, and thy father too, and, swords thrown down,

Made all shake hands, as once the Sabines did:

Thy death broke amity, and train’d to war

These captains emulous of each other’s glory.

Thou fear’d’st, great Pompey, that late deeds would dim

Old triumphs, and that Cæsar’s conquering France

Would dash the wreath thou war’st for pirates’ wreck:

Thee war’s use stirr’d, and thoughts that always scorn’d

A second place. Pompey could bide no equal,

Nor Cæsar no superior: which of both

Had justest cause, unlawful ’tis to judge:

Each side had great partakers; Cæsar’s cause

The gods abetted, Cato lik’d the other.[591]

Both differ’d much. Pompey was struck in years,

And by long rest forgot to manage arms,

And, being popular, sought by liberal gifts

To gain the light unstable commons’ love,

And joy’d to hear his theatre’s applause:

He lived secure, boasting his former deeds,

And thought his name sufficient to uphold him:

Like to a tall oak in a fruitful field,

Bearing old spoils and conquerors’ monuments,

Who, though his root be weak, and his own weight

Keep him within the ground, his arms all bare,

His body, not his boughs, send forth a shade;

Though every blast it nod,[592] and seem to fall,

When all the woods about stand bolt upright,

Yet he alone is held in reverence.

Cæsar’s renown for war was loss; he restless,

Shaming to strive but where he did subdue;

When ire or hope provok’d, heady and bold;

At all times charging home, and making havoc;

Urging his fortune, trusting in the gods,

Destroying what withstood his proud desires,

And glad when blood and ruin made him way:

So thunder, which the wind tears from the clouds,

With crack of riven air and hideous sound

Filling the world, leaps out and throws forth fire,

Affrights poor fearful men, and blasts their eyes

With overthwarting flames, and raging shoots

Alongst the air, and, not resisting it,

Falls, and returns, and shivers where it lights.

Such humours stirr’d them up; but this war’s seed

Was even the same that wrecks all great dominions.

When Fortune made us lords of all, wealth flow’d,

And then we grew licentious and rude;

The soldiers’ prey and rapine brought in riot;

Men took delight in jewels, houses, plate,

And scorn’d old sparing diet, and ware robes

Too light for women; Poverty, who hatch’d

Rome’s greatest wits,[593] was loath’d, and all the world

Ransack’d for gold, which breeds the world[‘s] decay;

And then large limits had their butting lands;

The ground, which Curius and Camillus till’d,

Was stretched unto the fields of hinds unknown.

Again, this people could not brook calm peace;

Them freedom without war might not suffice:

Quarrels were rife; greedy desire, still poor,

Did vild deeds; then ’twas worth the price of blood,

And deem’d renown, to spoil their native town;

Force mastered right, the strongest govern’d all;

Hence came it that th’ edicts were over-rul’d,

That laws were broke, tribunes with consuls strove,

Sale made of offices, and people’s voices

Bought by themselves and sold, and every year

Frauds and corruption in the Field of Mars;

Hence interest and devouring usury sprang,

Faith’s breach, and hence came war, to most men welcome.

Now Cæsar overpass’d the snowy Alps;

His mind was troubled, and he aim’d at war:

And coming to the ford of Rubicon,

At night in dreadful vision fearful[594] Rome

Mourning appear’d, whose hoary hairs were torn,

And on her turret-bearing head dispers’d,

And arms all naked; who, with broken sighs,

And staring, thus bespoke: “What mean’st thou, Cæsar?

Whither goes my standard? Romans if ye be,

And bear true hearts, stay here!” This spectacle

Struck Cæsar’s heart with fear; his hair stood up,

And faintness numb’d his steps there on the brink.

He thus cried out: “Thou thunderer that guard’st

Rome’s mighty walls, built on Tarpeian rock!

Ye gods of Phrygia and Iülus’ line,

Quirinus’ rites, and Latian Jove advanc’d

On Alba hill! O vestal flames! O Rome,

My thoughts sole goddess, aid mine enterprise!

I hate thee not, to thee my conquests stoop:

Cæsar is thine, so please it thee, thy soldier.

He, he afflicts Rome that made me Rome’s foe.”

This said, he, laying aside all lets[595] of war,

Approach’d the swelling stream with drum and ensign:

Like to a lion of scorch’d desert Afric,

Who, seeing hunters, pauseth till fell wrath

And kingly rage increase, then, having whisk’d

His tail athwart his back, and crest heav’d up,

With jaws wide-open ghastly roaring out,

Albeit the Moor’s light javelin or his spear

Sticks in his side, yet runs upon the hunter.

In summer-time the purple Rubicon,

Which issues from a small spring, is but shallow,

And creeps along the vales, dividing just

The bounds of Italy from Cisalpine France.

But now the winter’s wrath, and watery moon

Being three days old, enforc’d the flood to swell,

And frozen Alps thaw’d with resolving winds.

The thunder-hoof’d[596] horse, in a crookèd line,

To scape the violence of the stream, first waded;

Which being broke, the foot had easy passage.

As soon as Cæsar got unto the bank

And bounds of Italy, “Here, here,” saith he,

“An end of peace; here end polluted laws!

Hence leagues and covenants! Fortune, thee I follow!

War and the Destinies shall try my cause.”

This said, the restless general through the dark,

Swifter than bullets thrown from Spanish slings,

Or darts which Parthians backward shoot, march’d on;

And then, when Lucifer did shine alone,

And some dim stars, he Ariminum enter’d.

Day rose, and view’d these tumults of the war:

Whether the gods or blustering south were cause

I know not, but the cloudy air did frown.

The soldiers having won the market-place,

There spread the colours with confusèd noise

Of trumpets’ clang, shrill cornets, whistling fifes.

The people started; young men left their beds,

And snatch’d arms near their household-gods hung up,

Such as peace yields; worm-eaten leathern targets,

Through which the wood peer’d,[597] headless darts, old swords

With ugly teeth of black rust foully scarr’d.

But seeing white eagles, and Rome’s flags well known,

And lofty Cæsar in the thickest throng,

They shook for fear, and cold benumb’d their limbs,

And muttering much, thus to themselves complain’d:

“O walls unfortunate, too near to France!

Predestinate to ruin! all lands else

Have stable peace: here war’s rage first begins;

We bide the first brunt. Safer might we dwell

Under the frosty bear, or parching east,

Waggons or tents, than in this frontier town.

We first sustain’d the uproars of the Gauls

And furious Cimbrians, and of Carthage Moors:

As oft as Rome was sack’d, here gan the spoil.”

Thus sighing whisper’d they, and none durst speak,

And show their fear or grief; but as the fields

When birds are silent thorough winter’s rage,

Or sea far from the land, so all were whist,[598]

Now light had quite dissolv’d the misty night,

And Cæsar’s mind unsettled musing stood;

But gods and fortune pricked him to this war,

Infringing all excuse of modest shame,

And labouring to approve[599] his quarrel good.

The angry senate, urging Gracchus’[600] deeds,

From doubtful Rome wrongly expell’d the tribunes

That cross’d them: both which now approach’d the camp,

And with them Curio, sometime tribune too,

One that was fee’d for Cæsar, and whose tongue

Could tune the people to the nobles’ mind.[601]

“Cæsar,” said he, “while eloquence prevail’d,

And I might plead and draw the commons’ minds

To favour thee, against the senate’s will,

Five years I lengthen’d thy command in France;

But law being put to silence by the wars,

We, from her houses driven, most willingly

Suffer’d exile: let thy sword bring us home,

Now, while their part is weak and fears, march hence:

Where men are ready lingering ever hurts.[602]

In ten years wonn’st thou France: Rome may be won

With far less toil, and yet the honour’s more;

Few battles fought with prosperous success

May bring her down, and with her all the world.

Nor shalt thou triumph when thou com’st to Rome,

Nor Capitol be adorn’d with sacred bays;

Envy denies all; with thy blood must thou

Aby thy conquest past:[603] the son decrees

To expel the father: share the world thou canst not;

Enjoy it all thou mayst.” Thus Curio spake;

And therewith Cæsar, prone enough to war,

Was so incens’d as are Elean[604] steeds.

With clamours, who, though lock’d and chain’d in stalls,[605]

Souse[606] down the walls, and make a passage forth.

Straight summon’d he his several companies

Unto the standard: his grave look appeas’d

The wrestling tumult, and right hand made silence;

And thus he spake: “You that with me have borne

A thousand brunts, and tried me full ten years,

See how they quit our bloodshed in the north,

Our friends’ death, and our wounds, our wintering

Under the Alps! Rome rageth now in arms

As if the Carthage Hannibal were near;

Cornets of horse are muster’d for the field;

Woods turn’d to ships; both land and sea against us.

Had foreign wars ill-thriv’d, or wrathful France

Pursu’d us hither, how were we bested,

When, coming conqueror, Rome afflicts me thus?

Let come their leader[607] whom long peace hath quail’d,

Raw soldiers lately press’d, and troops of gowns,

Babbling[608] Marcellus, Cato whom fools reverence!

Must Pompey’s followers, with strangers’ aid

(Whom from his youth he brib’d), needs make him king?

And shall he triumph long before his time,

And, having once got head, still shall he reign?

What should I talk of men’s corn reap’d by force,

And by him kept of purpose for a dearth?

Who sees not war sit by the quivering judge,

And sentence given in rings of naked swords,

And laws assail’d, and arm’d men in the senate?

‘Twas his troop hemm’d in Milo being accus’d;

And now, lest age might wane his state, he casts

For civil war, wherein through use he’s known

To exceed his master, that arch-traitor Sylla.

A[s] brood of barbarous tigers, having lapp’d

The blood of many a herd, whilst with their dams

They kennell’d in Hyrcania, evermore

Will rage and prey; so, Pompey, thou, having lick’d

Warm gore from Sylla’s sword, art yet athirst:

Jaws flesh[ed] with blood continue murderous.

Speak, when shall this thy long-usurped power end?

What end of mischief? Sylla teaching thee,

At last learn, wretch, to leave thy monarchy!

What, now Sicilian[609] pirates are suppress’d,

And jaded[610] king of Pontus poison’d slain,

Must Pompey as his last foe plume on me,

Because at his command I wound not up

My conquering eagles? say I merit naught,[611]

Yet, for long service done, reward these men,

And so they triumph, be’t with whom ye will.

Whither now shall these old bloodless souls repair?

What seats for their deserts? what store of ground

For servitors to till? what colonies

To rest their bones? say, Pompey, are these worse

Than pirates of Sicilia?[612] they had houses.

Spread, spread these flags that ten years’ space have conquer’d!

Let’s use our tried force: they that now thwart right,

In wars will yield to wrong:[613] the gods are with us;

Neither spoil nor kingdom seek we by these arms,

But Rome, at thraldom’s feet, to rid from tyrants.”

This spoke, none answer’d, but a murmuring buzz

Th’ unstable people made: their household-gods

And love to Rome (though slaughter steel’d their hearts,

And minds were prone) restrain’d them; but war’s love

And Cæsar’s awe dash’d all. Then Lælius,[614]

The chief centurion, crown’d with oaken leaves

For saving of a Roman citizen,

Stepp’d forth, and cried: “Chief leader of Rome’s force,

So be I may be bold to speak a truth,

We grieve at this thy patience and delay.

What, doubt’st thou us? even now when youthful blood

Pricks forth our lively bodies, and strong arms

Can mainly throw the dart, wilt thou endure

These purple grooms, that senate’s tyranny?

Is conquest got by civil war so heinous?

Well, lead us, then, to Syrtes’ desert shore,

Or Scythia, or hot Libya’s thirsty sands.

This band, that all behind us might be quail’d,

Hath with thee pass’d the swelling ocean,

And swept the foaming breast of Arctic[615] Rhene.

Love over-rules my will; I must obey thee,

Cæsar: he whom I hear thy trumpets charge,

I hold no Roman; by these ten blest ensigns

And all thy several triumphs, shouldst thou bid me

Entomb my sword within my brother’s bowels,

Or father’s throat, or women’s groaning[616] womb,

This hand, albeit unwilling, should perform it?

Or rob the gods, or sacred temples fire,

These troops should soon pull down the church of Jove;[617]

If to encamp on Tuscan Tiber’s streams,

I’ll boldly quarter out the fields of Rome;

What walls thou wilt be levell’d with the ground,

These hands shall thrust the ram, and make them fly,

Albeit the city thou wouldst have so raz’d

Be Rome itself.” Here every band applauded,

And, with their hands held up, all jointly cried

They’ll follow where he please. The shouts rent heaven,

As when against pine-bearing Ossa’s rocks

Beats Thracian Boreas, or when trees bow[618] down

And rustling swing up as the wind fets[619] breath.

When Cæsar saw his army prone to war,

And Fates so bent, lest sloth and long delay

Might cross him, he withdrew his troops from France,

And in all quarters musters men for Rome.

They by Lemannus’ nook forsook their tents;

They whom[620] the Lingones foil’d with painted spears,

Under the rocks by crookèd Vogesus;

And many came from shallow Isara,

Who, running long, falls in a greater flood,

And, ere he sees the sea, loseth his name;

The yellow Ruthens left their garrisons;

Mild Atax glad it bears not Roman boats,[621]

And frontier Varus that the camp is far,

Sent aid; so did Alcides’ port, whose seas

Eat hollow rocks, and where the north-west wind

Nor zephyr rules not, but the north alone

Turmoils the coast, and enterance forbids;

And others came from that uncertain shore

Which is nor sea nor land, but ofttimes both,

And changeth as the ocean ebbs and flows;

Whether the sea roll’d always from that point

Whence the wind blows, still forcèd to and fro;

Or that the wandering main follow the moon;

Or flaming Titan, feeding on the deep,

Pulls them aloft, and makes the surge kiss heaven;

Philosophers, look you; for unto me,

Thou cause, whate’er thou be, whom God assigns

This great effect, art hid. They came that dwell

By Nemes’ fields and banks of Satirus,[622]

Where Tarbell’s winding shores embrace the sea;

The Santons that rejoice in Cæsar’s love;[623]

Those of Bituriges,[624] and light Axon[625] pikes;

And they of Rhene and Leuca,[626] cunning darters,

And Sequana that well could manage steeds;

The Belgians apt to govern British cars;

Th’ A[r]verni, too, which boldly feign themselves

The Roman’s brethren, sprung of Ilian race;

The stubborn Nervians stain’d with Cotta’s blood;

And Vangions who, like those of Sarmata,

Wear open slops;[627] and fierce Batavians,

Whom trumpet’s clang incites; and those that dwell

By Cinga’s stream, and where swift Rhodanus

Drives Araris to sea; they near the hills,

Under whose hoary rocks Gebenna hangs;

And, Trevier, thou being glad that wars are past thee;

And you, late-shorn Ligurians, who were wont

In large-spread hair to exceed the rest of France;

And where to Hesus and fell Mercury[628]

They offer human flesh, and where Jove seems

Bloody like Dian, whom the Scythians serve.

And you, French Bardi, whose immortal pens

Renown the valiant souls slain in your wars,

Sit safe at home and chant sweet poesy.

And, Druides, you now in peace renew

Your barbarous customs and sinister rites:

In unfell’d woods and sacred groves you dwell;

And only gods and heavenly powers you know,

Or only know you nothing; for you hold

That souls pass not to silent Erebus

Or Pluto’s bloodless kingdom, but elsewhere

Resume a body; so (if truth you sing)

Death brings long life. Doubtless these northern men,

Whom death, the greatest of all fears, affright not,

Are blest by such sweet error; this makes them

Run on the sword’s point, and desire to die,

And shame to spare life which being lost is won.

You likewise that repuls’d the Caÿc foe,

March towards Rome; and you, fierce men of Rhene,

Leaving your country open to the spoil.

These being come, their huge power made him bold

To manage greater deeds; the bordering towns

He garrison’d; and Italy he fill’d with soldiers.

Vain fame increased true fear, and did invade

The people’s minds, and laid before their eyes

Slaughter to come, and, swiftly bringing news

Of present war, made many lies and tales:

One swears his troops of daring horsemen fought

Upon Mevania’s plain, where bulls are graz’d;

Other that Cæsar’s barbarous bands were spread

Along Nar flood that into Tiber falls,

And that his own ten ensigns and the rest

March’d not entirely, and yet hide the ground;

And that he’s much chang’d, looking wild and big,

And far more barbarous than the French, his vassals;

And that he lags[629] behind with them, of purpose,

Borne ‘twixt the Alps and Rhene, which he hath brought

From out their northern parts,[630] and that Rome,

He looking on, by these men should be sack’d.

Thus in his fright did each man strengthen fame,

And, without ground, fear’d what themselves had feign’d.

Nor were the commons only struck to heart

With this vain terror; but the court, the senate,

The fathers selves leap’d from their seats, and, flying,

Left hateful war decreed to both the consuls.

Then, with their fear and danger all-distract,

Their sway of flight carries the heady rout,[631]

That in chain’d[632] troops break forth at every port:

You would have thought their houses had been fir’d,

Or, dropping-ripe, ready to fall with ruin.

So rush’d the inconsiderate multitude

Thorough the city, hurried headlong on,

As if the only hope that did remain

To their afflictions were t’ abandon Rome.

Look how, when stormy Auster from the breach

Of Libyan Syrtes rolls a monstrous wave,

Which makes the main-sail fall with hideous sound,

The pilot from the helm leaps in the sea,

And mariners, albeit the keel be sound,

Shipwreck themselves; even so, the city left,

All rise in arms; nor could the bed-rid parents

Keep back their sons, or women’s tears their husbands:

They stayed not either to pray or sacrifice;

Their household-gods restrain them not; none lingered,

As loath to leave Rome whom they held so dear:

Th’ irrevocable people fly in troops.

O gods, that easy grant men great estates,

But hardly grace to keep them! Rome, that flows

With citizens and captives,[633] and would hold

The world, were it together, is by cowards

Left as a prey, now Cæsar doth approach.

When Romans are besieged by foreign foes,

With slender trench they escape night-stratagems,

And sudden rampire rais’d of turf snatched up,

Would make them sleep securely in their tents.

Thou, Rome, at name of war runn’st from thyself,

And wilt not trust thy city-walls one night:

Well might these fear, when Pompey feared and fled.

Now evermore, lest some one hope might ease

The commons’ jangling minds, apparent signs arose,

Strange sights appeared; the angry threatening gods

Filled both the earth and seas with prodigies.

Great store of strange and unknown stars were seen

Wandering about the north, and rings of fire

Fly in the air, and dreadful bearded stars,

And comets that presage the fall of kingdoms;

The flattering[634] sky glittered in often flames,

And sundry fiery meteors blazed in heaven,

Now spear-like long, now like a spreading torch;

Lightning in silence stole forth without clouds,

And, from the northern climate snatching fire,

Blasted the Capitol; the lesser stars,

Which wont to run their course through empty night,

At noon-day mustered; Phœbe, having filled

Her meeting horns to match her brother’s light,

Struck with th’ earth’s sudden shadow, waxèd pale;

Titan himself, throned in the midst of heaven,

His burning chariot plunged in sable clouds,

And whelmed the world in darkness, making men

Despair of day; as did Thyestes’ town,

Mycenæ, Phœbus flying through the east.

Fierce Mulciber unbarrèd Ætna’s gate,

Which flamèd not on high, but headlong pitched

Her burning head on bending Hespery.

Coal-black Charybdis whirled a sea of blood.

Fierce mastives howled. The vestal fires went out;

The flame in Alba, consecrate to Jove,

Parted in twain, and with a double point

Rose, like the Theban brothers’ funeral fire.

The earth went off her hinges; and the Alps

Shook the old snow from off their trembling laps.[635]

The ocean swelled as high as Spanish Calpe

Or Atlas’ head. Their saints and household-gods

Sweat tears, to show the travails of their city:

Crowns fell from holy statues. Ominous birds

Defiled the day; and wild beasts were seen,[636]

Leaving the woods, lodge in the streets of Rome.

Cattle were seen that muttered human speech;

Prodigious births with more and ugly joints

Than nature gives, whose sight appals the mother;

And dismal prophecies were spread abroad:

And they, whom fierce Bellona’s fury moves

To wound their arms, sing vengeance; Cybel’s[637] priests,

Curling their bloody locks, howl dreadful things.

Souls quiet and appeas’d sighed from their graves;

Clashing of arms was heard; in untrod woods

Shrill voices schright;[638] and ghosts encounter men.

Those that inhabited the suburb-fields

Fled: foul Erinnys stalked about the walls,

Shaking her snaky hair and crookèd pine

With flaming top; much like that hellish fiend

Which made the stern Lycurgus wound his thigh,

Or fierce Agave mad; or like Megæra

That scar’d Alcides, when by Juno’s task

He had before look’d Pluto in the face.

Trumpets were heard to sound; and with what noise

An armèd battle joins, such and more strange

Black night brought forth in secret. Sylla’s ghost

Was seen to walk, singing sad oracles;

And Marius’ head above cold Tav’ron[639] peering,

His grave broke open, did affright the boors.

To these ostents, as their old custom was,

They call th’ Etrurian augurs: amongst whom

The gravest, Arruns, dwelt in forsaken Leuca[640]

Well-skill’d in pyromancy; one that knew

The hearts of beasts, and flight of wandering fowls.

First he commands such monsters Nature hatch’d

Against her kind, the barren mule’s loath’d issue,

To be cut forth[641] and cast in dismal fires;

Then, that the trembling citizens should walk

About the city; then, the sacred priests

That with divine lustration purg’d the walls,

And went the round, in and without the town;

Next, an inferior troop, in tuck’d-up vestures,

After the Gabine manner; then, the nuns

And their veil’d matron, who alone might view

Minerva’s statue; then, they that kept and read

Sibylla’s secret works, and wash[642] their saint

In Almo’s flood; next learnèd augurs follow;

Apollo’s soothsayers, and Jove’s feasting priests;

The skipping Salii with shields like wedges;

And Flamens last, with net-work woollen veils.

While these thus in and out had circled Rome,

Look, what the lightning blasted, Arruns takes,

And it inters with murmurs dolorous,

And calls the place Bidental. On the altar

He lays a ne’er-yok’d bull, and pours down wine,

Then crams salt leaven on his crookèd knife:

The beast long struggled, as being like to prove

An awkward sacrifice; but by the horns

The quick priest pulled him on his knees, and slew him.

No vein sprung out, but from the yawning gash,

Instead of red blood, wallow’d venomous gore.

These direful signs made Arruns stand amazed,

And searching farther for the gods’ displeasure,

The very colour scared him; a dead blackness

Ran through the blood, that turned it all to jelly,

And stained the bowels with dark loathsome spots;

The liver swelled with filth; and every vein

Did threaten horror from the host of Cæsar

A small thin skin contained the vital parts;

The heart stirred not; and from the gaping liver

Squeezed matter through the caul; the entrails peered;

And which (ay me!) ever pretendeth[643] ill,

At that bunch where the liver is, appear’d

A knob of flesh, whereof one half did look

Dead and discolour’d, th’ other lean and thin.[644]

By these he seeing what mischiefs must ensue,

Cried out, “O gods, I tremble to unfold

What you intend! great Jove is now displeas’d;

And in the breast of this slain bull are crept

Th’ infernal powers. My fear transcends my words;

Yet more will happen than I can unfold:

Turn all to good, be augury vain, and Tages,

Th’ art’s master, false!” Thus, in ambiguous terms

Involving all, did Arruns darkly sing.

But Figulus, more seen in heavenly mysteries,

Whose like Ægyptian Memphis never had

For skill in stars and tuneful planeting,[645]

In this sort spake: “The world’s swift course is lawless

And casual; all the stars at random range;[646]

Or if fate rule them, Rome, thy citizens

Are near some plague. What mischief shall ensue?

Shall towns be swallow’d? shall the thicken’d air

Become intemperate? shall the earth be barren?

Shall water be congeal’d and turn’d to ice?[647]

O gods, what death prepare ye? with what plague

Mean ye to rage? the death of many men

Meets in one period. If cold noisome Saturn

Were now exalted, and with blue beams shin’d,

Then Ganymede[648] would renew Deucalion’s flood,

And in the fleeting sea the earth be drench’d.

O Phœbus, shouldst thou with thy rays now singe

The fell Nemæan beast, th’ earth would be fir’d,

And heaven tormented with thy chafing heat:

But thy fires hurt not. Mars, ’tis thou inflam’st

The threatening Scorpion with the burning tail,

And fir’st his cleys:[649] why art thou thus enrag’d?

Kind Jupiter hath low declin’d himself;

Venus is faint; swift Hermes retrograde;

Mars only rules the heaven. Why do the planets

Alter their course, and vainly dim their virtue?

Sword-girt Orion’s side glisters too bright:

War’s rage draws near; and to the sword’s strong hand

Let all laws yield, sin bears the name of virtue:

Many a year these furious broils let last:

Why should we wish the gods should ever end them?

War only gives us peace. O Rome, continue

The course of mischief, and stretch out the date

Of slaughter! only civil broils make peace.”

These sad presages were enough to scare

The quivering Romans; but worse things affright them.

As Mænas[650] full of wine on Pindus raves,

So runs a matron through th’ amazèd streets,

Disclosing Phœbus’ fury in this sort;

“Pæan, whither am I haled? where shall I fall,

Thus borne aloft? I seen Pangæus’ hill

With hoary top, and, under Hæmus’ mount,

Philippi plains. Phœbus, what rage is this?

Why grapples Rome, and makes war, having no foes?

Whither turn I now? thou lead’st me toward th’ east,

Where Nile augmenteth the Pelusian sea:

This headless trunk that lies on Nilus’ sand

I know. Now th[o]roughout the air I fly

To doubtful Syrtes and dry Afric, where

A Fury leads the Emathian bands. From thence

To the pine-bearing[651] hills; thence[652] to the mounts

Pyrene; and so back to Rome again.

See, impious war defiles the senate-house!

New factions rise. Now through the world again

I go. O Phœbus, show me Neptune’s shore,

And other regions! I have seen Philippi.”

This said, being tir’d with fury, she sunk down.

THE FIRST BOOK OF LUCAN FOOTNOTES:

[579] Old ed. “launcht.”—The forms “lanch” and “lance” are used indifferently.

[580] Alike.

[581] “Et ardenti servilia bella sub Ætna.”

[582] “Nec polus adversi calidus qua vergitur Austri.”

[583] “Obliquo sidere.”

[584] Axis.

[585] Tumults.

“Summisque negatum,

Stare diu.”

[587] Far-fetched.

[588] “Exiguum dominos commisit asylum.”

[589] “So old ed. in some copies which had been corrected at press; other copies ‘Aezean.'”—Dyce.

[590] Carræ’s.

[591] A somewhat weak translation of Lucan’s most famous line:—”Victrix causa diis placuit, sed victa Catoni.”

[592] As the line stands we must take “nod” and “fall” transitively (“though every blast make it nod and seem to make it fall”). The original has “At quamvis primo nutet casura sub Euro.”

[593] “Fecunda virorum / Paupertas.”

[594] “Ingens visa duci patriae trepidantis imago.”

[595] “Inde moras solvit belli.”

[596] “Sonipes.”

[597] “Nuda jam crate fluentes / Invadunt clypeos.”

[598] Silent.

[599] Prove.

[600] “Jactatis … Gracchis.”

[601] Marlowe omits to translate the words that follow in the original:—

“Utque ducem varias volventem pectore curas

Conspexit.”

[602] A line (omitted by Marlowe) follows in the original:—”Par labor atque metus pretio majore petuntur.”

[603] An obscure rendering of

“Gentesque subactas

Vix impune feres.”

[604] Old ed. “Eleius.” It is hardly possible to suppose (as Dyce suggests) that Marlowe took the adjective “Eleus” for a substantive.

[605] A mistranslation of “carcere clauso.” (“Carcer” is the barrier or starting-place in the circus.)

[606] “Immineat foribus.” “Souse” is a north-country word meaning to bang or dash. It is also applied to the swooping-down of a hawk.

[607] Old ed. “leaders.”

[608] So Dyce for the old ed’s. “Brabbling.” The original has “Marcellusque loquax.” (“Brabbling” means “wrangling.”)

[609] A mistake (or perhaps merely a misprint) for “Cilician.”

[610] Old ed. has “Jaded, king of Pontus!”

[611] “Unless we understand this in the sense of—say I receive no reward (—and in Fletcher’s Woman-Hater, ‘merit’ means—derive profit, B. and F.’s Works, i. 91, ed. Dyce,—), it is a wrong translation of ‘mihi si merces erepta laborum est.'”—Dyce.

[612] “Sicilia” should be “Cilicia.”

[613] A free translation of the frigid original—

“Arma tenenti

Omnia dat qui justa negat.”

[614] Old ed. “Lalius.”

[615] Old ed. “Articks Rhene.” (“Rhene” is the old form of “Rhine.”)

[616] So old ed. Dyce’s correction “or groaning woman’s womb” seems hardly necessary. (The original has “plenaeque in viscera partu conjugis.”)

[617] “Numina miscebit castrensis flamma Monetae.”

[618] Old ed. “bowde.”

[619] Fetches.

[620] The original has—

“Castraque quae, Vogesi curvam super ardua rupem,

Pugnaces pictis cohibebant Lingonas armis.”

Dyce conjectures that Marlowe’s copy read Lingones.

[621] Old ed. “bloats.”

“Tunc rura Nemossi

Qui tenet et ripas Aturi.”

[623] Marlowe seems to have read here very ridiculously, “gaudetque amato [instead of amoto] Santonus hoste.”—Dyce.

[624] Marlowe has converted the name of a tribe into that of a country.

[625] The approved reading is “longisque leves Suessones in armis.”

[626] “Optimus excusso Leucus Rhemusque lacerto.”

[627] “Et qui te laxis imitantur, Sarmata, bracchis Vangiones.”

Marlowe has mistaken “Sarmata,” a Sarmatian, for the country Sarmatia.

[628] The old ed. gives “fell Mercury (Joue),” and in the next line “where it seems.” “Jove” written, as a correction, in the MS. above “it” was supposed by the printer to belong to the previous line.

[629] The original has—

“Hunc inter Rhenum populos Alpesque jacentes, / Finibus Arctois patriaque a sede revulsos, / Pone sequi.”/ (“Populos” is the subject and “Hunc” the object of “sequi.” For “Hunc” the best editions give “Tunc.”)

[630] “Parts” must be pronounced as a dissyllable.

[631] “Praecipitem populum.”

[632] “Serieque haerentia longa / Agmina prorumpunt.”

[633] “Urbem populis, victisque frequentem Gentibus.”—Old ed. “captaines.”

[634] “Fulgura fallaci micuerunt crebra sereno.”

[635] The original has, “jugis nutantibus.” Dyce reads “tops,”—an emendation against which Cunningham loudly protests. “Laps” is certainly more emphatic.

[636] The line is imperfect. We should have expected “at night wild beasts were seen” (“silvisque feras sub nocte relictis”).

[637] Old ed. “Sibils.”

[638] Shrieked.

[639] “Gelidas Anienis ad undas.”

[640] “Or Lunæ”—marginal note in old ed.

[641] The original has “rapi.”

[642] Old ed. “wash’d.”

[643] Portendeth.

[644] Here Marlowe quite deserts the original—

“pars ægra et marcida pendet,

Pars micat, et celeri venas movet improba pulsu.”

[645] “Numerisque moventibus astra.”—The word “planeting” was, I suppose, coined by Marlowe. I have never met it elsewhere.

[646] So Dyce.—Old ed. “radge.” (The original has “et incerto discurrunt sidera motu.”)

[647] “Omnis an effusis miscebitur unda venenis.”—Dyce suggests that Marlowe’s copy read “pruinis.”

[648] The original has “Aquarius.”—Ganymede was changed into the sign Aquarius: see Hyginus’ Poeticon Astron. II. 29.

[649] Claws.

[650] A Mænad.—Old ed. “Mænus.”

[651] The original has “Nubiferæ.”

[652] Old ed. “hence.”

This is the only early edition. The title-page of the 1600 4to. of Hero and Leander has the words, “Whereunto is added the first booke of Lucan;” but the two pieces are not found in conjunction.