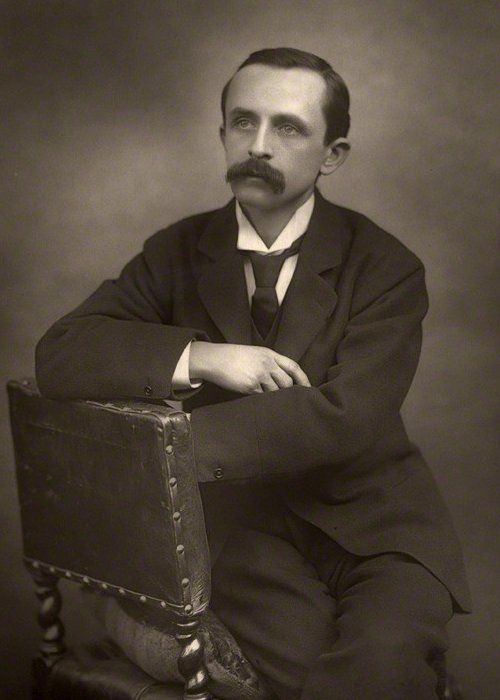

My Favorite Authoress by James Matthew Barrie

From A Holiday in Bed and Other Sketches by J. M. Barrie

My Favorite Authoress

Just out of the four-mile radius—to give the cabby his chance—is a sleepy lane, lent by the country to the town, and we have only to open a little gate off it to find ourselves in an old-fashioned garden. The house, with its many quaint windows, across which evergreens spread their open fingers as a child makes believe to shroud his eyes, has a literary look—at least, so it seems to me, but perhaps this is because I know the authoress who is at this moment advancing down the walk to meet me.

She has hastily laid aside her hoop, and crosses the grass with the dignity that becomes a woman of letters. Her hair falls over her forehead in an attractive way, and she is just the proper height for an authoress. The face, so open that one can watch the process of thinking out a new novel in it, from start to finish, is at times a little careworn, as if it found the world weighty, but at present there is a gracious smile on it, and she greets me heartily with one hand, while the other strays to her neck, to make sure that her lace collar is lying nicely. It would be idle to pretend that she is much more than eight years old, “but then Maurice is only six.”

Like most literary people who put their friends into books, she is very modest, and it never seems to strike her that I would come all this way to see her.

“Mamma is out,” she says simply, “but she will be back soon; and papa is at a meeting, but he will be back soon, too.”

I know what meeting her papa is at. He is crazed with admiration for Stanley, and can speak of nothing but the Emin Relief Expedition. While he is away proposing that Stanley should get the freedom of Hampstead, now is my opportunity to interview the authoress.

“Won’t you come into the house?”

I accompany the authoress to the house, while we chat pleasantly on literary topics.

“Oh, there is Maurice, silly boy!”

Maurice is too busy shooting arrows into the next garden to pay much attention to me; and the authoress smiles at him good-naturedly.

“I hope you’ll stay to dinner,” he says to me, “because then we’ll have two kinds of pudding.”

The authoress and I give each other a look which means that children will be children, and then we go indoors.

“Are you not going to play any more?” cries Maurice to the authoress.

She blushes a little.

“I was playing with him,” she explains, “to keep him out of mischief till mamma comes back.”

In the drawing-room we talk for a time of ordinary matters—of the allowances one must make for a child like Maurice, for instance—and gradually we drift to the subject of literature. I know literary people sufficiently well to be aware that they will talk freely—almost too freely—of their work if approached in the proper spirit.

“Are you busy just now?” I ask, with assumed carelessness, and as if I had not been preparing the question since I heard papa was out.

She looks at me, suspiciously, as authors usually do when asked such a question. They are not certain whether you are really sympathetic. However, she reads honesty in my eyes.

“Oh, well, I am doing a little thing.” (They always say this.)

“A story or an article?”

“A story.”

“I hope it will be good.”

“I don’t know. I don’t like it much.” (This is another thing they say, and then they wait for you to express incredulity.)

“I have no doubt it will be a fine thing. Have you given it a name?”

“Oh, yes; I always write the name. Sometimes I don’t write any more.”

As she was in a confidential mood this seemed an excellent chance for getting her views on some of the vexed literary questions of the day. For instance, everybody seems to be more interested in hearing during what hours of the day an author writes than in reading his book.

“Do you work best in the early part of the day or at night?”

“I write my stories just before tea.”

“That surprises me. Most writers, I have been told, get through a good deal of work in the morning.”

“Oh, but I go to school as soon as breakfast is over.”

“And you don’t write at night?”

“No; nurse always turns the gas down.”

I had read somewhere that among the novelist’s greatest difficulties is that of sustaining his own interest in a novel day by day until it is finished.

“Until your new work is completed do you fling your whole heart and soul into it? I mean, do you work straight on at it, so to speak, until you have finished the last chapter?”

“Oh, yes.”

The novelists were lately reproved in a review for working too quickly, and it was said that one wrote a whole novel in two months.

“How long does it take you to write a novel?”

“Do you mean a long novel?”

“Yes.”

“It takes me nearly an hour.”

“For a really long novel?”

“Yes, in three volumes. I write in three exercise-books—a volume in each.”

“You write very quickly.”

“Of course, a volume doesn’t fill a whole exercise-book. They are penny exercise-books. I have a great many three-volume stories in the three exercise-books.”

“But are they really three-volume novels?”

“Yes, for they are in chapters, and one of them has twenty chapters.”

“And how many chapters are there in a page?”

“Not very many.”

Some authors admit that they take their characters from real life, while others declare that they draw entirely upon their imagination.

“Do you put real people into your novels?”

“Yes, Maurice and other people, but generally Maurice.”

“I have heard that some people are angry with authors for putting them into books.”

“Sometimes Maurice is angry, but I can’t always make him an engine-driver, can I?”

“No. I think it is quite unreasonable on his part to expect it. I suppose he likes to be made an engine-driver?”

“He is to be an engine-driver when he grows up, he says. He is a silly boy, but I love him.”

“What else do you make him in your books?”

“To-day I made him like Stanley, because I think that is what papa would like him to be; and yesterday he was papa, and I was his coachman.”

“He would like that?”

“No, he wanted me to be papa and him the coachman. Sometimes I make him a pirate, and he likes that, and once I made him a girl.”

“He would be proud?”

“That was the day he hit me. He is awfully angry if I make him a girl, silly boy. Of course he doesn’t understand.”

“Obviously not. But did you not punish him for being so cruel as to hit you?”

“Yes, I turned him into a cat, but he said he would rather be a cat than a girl. You see he’s not much more than a baby—though I was writing books at his age.”

“Were you ever charged with plagiarism? I mean with copying your books out of other people’s books.”

“Yes, often.”

“I suppose that is the fate of all authors. I am told that literary people write best in an old coat——.”

“Oh, I like to be nicely dressed when I am writing. Here is papa, and I do believe he has another portrait of Stanley in his hand. Mamma will be so annoyed.”