TOMMY AND GRIZEL by James Matthew Barrie

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER I. HOW TOMMY FOUND A WAY

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER II. THE SEARCH FOR THE TREASURE

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER III. SANDYS ON WOMAN

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER IV. GRIZEL OF THE CROOKED SMILE

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER V. THE TOMMY MYTH

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER VI. GHOSTS THAT HAUNT THE DEN

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER VII. THE BEGINNING OF THE DUEL

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER VIII. WHAT GRIZEL’S EYES SAID

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER IX. GALLANT BEHAVIOUR OF T. SANDYS

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER X. GAVINIA ON THE TRACK

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XI. THE TEA-PARTY

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XII. IN WHICH A COMEDIAN CHALLENGES TRAGEDY TO BOWLS

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XIII. LITTLE WELLS OF GLADNESS

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XIV. ELSPETH

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XV. BY PROSEN WATER

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XVI. “HOW COULD YOU HURT YOUR GRIZEL SO!”

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XVII. HOW TOMMY SAVED THE FLAG

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XVIII. THE GIRL SHE HAD BEEN

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XIX. OF THE CHANGE IN THOMAS

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XX. A LOVE-LETTER

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXI. THE ATTEMPT TO CARRY ELSPETH BY NUMBERS

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXII. GRIZEL’S GLORIOUS HOUR

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXIII. TOMMY LOSES GRIZEL

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXIV. THE MONSTER

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXV. MR. T. SANDYS HAS RETURNED TO TOWN

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXVI. GRIZEL ALL ALONE

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXVII. GRIZEL’S JOURNEY

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXVIII. TWO OF THEM

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXIX. THE RED LIGHT

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXX. THE LITTLE GODS DESERT HIM

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXXI. “THE MAN WITH THE GREETIN’ EYES”

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXXII. TOMMY’S BEST WORK

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXXIII. THE LITTLE GODS RETURN WITH A LADY

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXXIV. A WAY IS FOUND FOR TOMMY

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XXXV. THE PERFECT LOVER

TOMMY AND GRIZEL CHAPTER XIII LITTLE WELLS OF GLADNESS

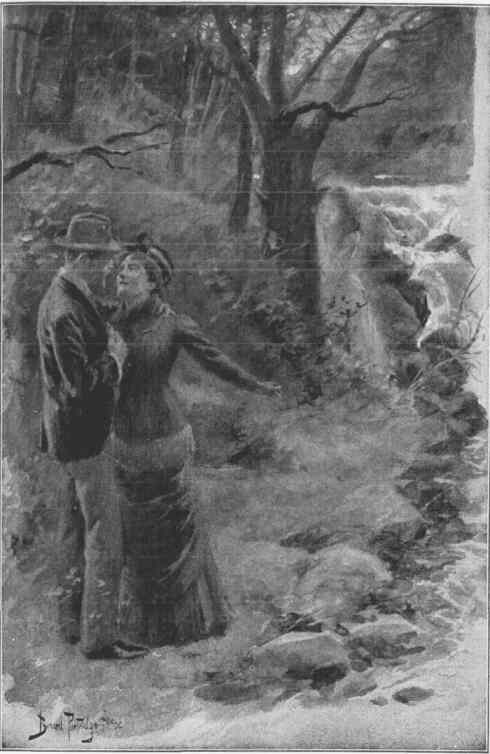

It was dusk, and she had not seen him. In the silent Den he stood motionless within a few feet of her, so amazed to find that Grizel really loved him that for the moment self was blotted out of his mind. He remembered he was there only when he heard his heavy breathing, and then he tried to check it that he might steal away undiscovered. Divers emotions fought for the possession of him. He was in the meeting of many waters, each capable of whirling him where it chose, but two only imperious: the one the fierce joy of being loved; the other an agonizing remorse. He would fain have stolen away to think this tremendous thing over, but it tossed him forward. “Grizel,” he said in a husky whisper, “Grizel!”

She did not start; she was scarcely surprised to hear his voice: she had been talking to him, and he had answered. Had he not been there she would still have heard him answer. She could not see him more clearly now than she had been seeing him through those little wells of gladness. Her love for him was the whole of her. He came to her with the opening and the shutting of her eyes; he was the wind that bit her and the sun that nourished her; he was the lowliest object by the Cuttle Well, and he was the wings on which her thoughts soared to eternity. He could never leave her while her mortal frame endured.

When he whispered her name she turned her swimming eyes to him, and a strange birth had come into her face. Her eyes said so openly they were his, and her mouth said it was his, her whole being went out to him; in the radiance of her face could be read immortal designs: the maid kissing her farewell to innocence was there, and the reason why it must be, and the fate of the unborn; it was the first stirring for weal or woe of a movement that has no end on earth, but must roll on, growing lusty on beauty or dishonour till the crack of time. This birth which comes to every woman at that hour is God’s gift to her in exchange for what He has taken away, and when He has given it He stands back and watches the man.

To this man she was a woman transformed. The new bloom upon her face entranced him. He knew what it meant. He was looking on the face of love at last, and it was love coming out smiling from its hiding-place because it thought it had heard him call. The artist in him who had done this thing was entranced, as if he had written an immortal page.

But the man was appalled. He knew that he had reached the critical moment in her life and his, and that if he took one step farther forward he could never again draw back. It would be comparatively easy to draw back now. To remain a free man he had but to tell her the truth; and he had a passionate desire to remain free. He heard the voices of his little gods screaming to him to draw back. But it could be done only at her expense, and it seemed to him that to tell this noble girl, who was waiting for him, that he did not need her, would be to spill for ever the happiness with which she overflowed, and sap the pride that had been the marrow of her during her twenty years of life. Not thus would Grizel have argued in his place; but he could not change his nature, and it was Sentimental Tommy, in an agony of remorse for having brought dear Grizel to this pass, who had to decide her future and his in the time you may take to walk up a garden path. Either her mistake must be righted now or kept hidden from her for ever. He was a sentimentalist, but in that hard moment he was trying to be a man. He took her in his arms and kissed her reverently, knowing that after this there could be no drawing back. In that act he gave himself loyally to her as a husband. He knew he was not worthy of her, but he was determined to try to be a little less unworthy; and as he drew her to him a slight quiver went through her, so that for a second she seemed to be holding back—for a second only, and the quiver was the rustle of wings on which some part of the Grizel we have known so long was taking flight from her. Then she pressed close to him passionately, as if she grudged that pause. I love her more than ever, far more; but she is never again quite the Grizel we have known.

He was not unhappy; in the near hereafter he might be as miserable as the damned—the little gods were waiting to catch him alone and terrify him; but for the time, having sacrificed himself, Tommy was aglow with the passion he had inspired. He so loved the thing he had created that in his exultation he mistook it for her. He believed all he was saying. He looked at her long and adoringly, not, as he thought, because he adored her, but because it was thus that look should answer look; he pressed her wet eyes reverently because thus it was written in his delicious part; his heart throbbed with hers that they might beat in time. He did not love, but he was the perfect lover; he was the artist trying in a mad moment to be as well as to do. Love was their theme; but how to know what was said when between lovers it is only the loose change of conversation that gets into words? The important matters cannot wait so slow a messenger; while the tongue is being charged with them, a look, a twitch of the mouth, a movement of a finger, transmits the story, and the words arrive, like Blücher, when the engagement is over.

With a sudden pretty gesture—ah, so like her mother’s!—she held the glove to his lips. “It is sad because you have forgotten it.”

“I have kissed it so often, Grizel, long before I thought I should ever kiss you!”

She pressed it to her innocent breast at that. And had he really done so? and which was the first time, and the second, and the third? Oh, dear glove, you know so much, and your partner lies at home in a drawer knowing nothing. Grizel felt sorry for the other glove. She whispered to Tommy as a terrible thing, “I think I love this glove even more than I love you—just a tiny bit more.” She could not part with it. “It told me before you did,” she explained, begging him to give it back to her.

“If you knew what it was to me in those unhappy days, Grizel!”

“I want it to tell me,” she whispered.

And did he really love her? Yes, she knew he did, but how could he?

“Oh, Grizel, how could I help it!”

He had to say it, for it is the best answer; but he said it with a sigh, for it sounded like a quotation.

But how could she love him? I think her reply disappointed him.

“Because you wanted me to,” she said, with shining eyes. It is probably the commonest reason why women love, and perhaps it is the best; but his vanity was wounded—he had expected to hear that he was possessed of an irresistible power.

“Not until I wanted you to?”

“I think I always wanted you to want me to,” she replied, naïvely; “but I would never have let myself love you,” she continued very seriously, “until I was sure you loved me.”

“You could have helped it, Grizel!” He drew a blank face.

“I did help it,” she answered. “I was always fighting the desire to love you,—I can see that plainly,—and I always won. I thought God had made a sort of compact with me that I should always be the kind of woman I wanted to be if I resisted the desire to love you until you loved me.”

“But you always had the desire!” he said eagerly.

“Always, but it never won. You see, even you did not know of it. You thought I did not even like you! That was why you wanted to prevent Corp’s telling me about the glove, was it not? You thought it would pain me only! Do you remember what you said: ‘It is to save you acute pain that I want to see Corp first’?”

All that seemed so long ago to Tommy now!

“How could you think it would be a pain to me!” she cried.

“You concealed your feelings so well, Grizel.”

“Did I not?” she said joyously. “Oh, I wanted to be so careful, and I was careful. That is why I am so happy now.” Her face was glowing. She was full of odd, delightful fancies to-night. She kissed her hand to the gloaming; no, not to the gloaming—to the little hunted, anxious girl she had been.

‘She is standing behind that tree looking at us.’

“She is looking at us,” she said. “She is standing behind that tree looking at us. She wanted so much to grow into a dear, good woman that she often comes and looks at me eagerly. Sometimes her face is so fearful! I think she was a little alarmed when she heard you were coming back.”

“She never liked me, Grizel.”

“Hush!” said Grizel, in a low voice. “She always liked you; she always thought you a wonder. But she would be distressed if she heard me telling you. She thought it would not be safe for you to know. I must tell him now, dearest, darlingest,” she suddenly called out boldly to the little self she had been so quaintly fond of because there was no other to love her. “I must tell him everything now, for you are no longer your own. You are his.”

“She has gone away rocking her arms,” she said to Tommy.

“No,” he replied. “I can hear her. She is singing because you are so happy.”

“She never knew how to sing.”

“She has learned suddenly. Everybody can sing who has anything to sing about. And do you know what she said about your dear wet eyes, Grizel? She said they were just sweet. And do you know why she left us so suddenly? She ran home gleefully to stitch and dust and beat carpets, and get baths ready, and look after the affairs of everybody, which she is sure must be going to rack and ruin because she has been away for half an hour!”

At his words there sparkled in her face the fond delight with which a woman assures herself that the beloved one knows her little weaknesses, for she does not truly love unless she thirsts to have him understand the whole of her, and to love her in spite of the foibles and for them. If he does not love you a little for the foibles, madam, God help you from the day of the wedding.

But though Grizel was pleased, she was not to be cajoled. She wandered with him through the Den, stopping at the Lair, and the Queen’s Bower, and many other places where the little girl used to watch Tommy suspiciously; and she called, half merrily, half plaintively: “Are you there, you foolish girl, and are you wringing your hands over me? I believe you are jealous because I love him best.”

“We have loved each other so long, she and I,” she said apologetically to Tommy. “Ah,” she said impulsively, when he seemed to be hurt, “don’t you see it is because she doubts you that I am so sorry for the poor thing!”

“Dearest, darlingest,” she called to the child she had been, “don’t think that you can come to me when he is away, and whisper things against him to me. Do you think I will listen to your croakings, you poor, wet-faced thing!”

“You child!” said Tommy.

“Do you think me a child because I blow kisses to her?”

“Do you like me to think you one?” he replied.

“I like you to call me child,” she said, “but not to think me one.”

“Then I shall think you one,” said he, triumphantly. He was so perfect an instrument for love to play upon that he let it play on and on, and listened in a fever of delight. How could Grizel have doubted Tommy? The god of love himself would have sworn that there were a score of arrows in him. He wanted to tell Elspeth and the others at once that he and Grizel were engaged. I am glad to remember that it was he who urged this, and Grizel who insisted on its being deferred. He even pretended to believe that Elspeth would exult in the news; but Grizel smiled at him for saying this to please her. She had never been a great friend of Elspeth’s, they were so dissimilar; and she blamed herself for it now, and said she wanted to try to make Elspeth love her before they told her. Tommy begged her to let him tell his sister at once; but she remained obdurate, so anxious was she that her happiness, when revealed, should bring only happiness to others. There had not come to Grizel yet the longing to be recognized as his by the world. This love was so beautiful and precious to her that there was an added joy in sharing the dear secret with him alone; it was a live thing that might escape if she let anyone but him look between the fingers that held it.

The crowning glory of loving and being loved is that the pair make no real progress; however far they have advanced into the enchanted land during the day, they must start again from the frontier next morning. Last night they had dredged the lovers’ lexicon for superlatives and not even blushed; to-day is that the heavens cracking or merely someone whispering “dear”? All this was very strange and wonderful to Grizel. She had never been so young in the days when she was a little girl.

“I can never be quite so happy again!” she had said, with a wistful smile, on the night of nights; but early morn, the time of the day that loves maidens best, retold her the delicious secret as it kissed her on the eyes, and her first impulse was to hurry to Tommy. When joy or sorrow came to her now, her first impulse was to hurry with it to him.

Was he still the same, quite the same? She, whom love had made a child of, asked it fearfully, as if to gaze upon him openly just at first might be blinding; and he pretended not to understand. “The same as what, Grizel?”

“Are you still—what I think you?”

“Ah, Grizel, not at all what you think me.”

“But you do?”

“Coward! You are afraid to say the word. But I do!”

“You don’t ask whether I do!”

“No.”

“Why? Is it because you are so sure of me?”

He nodded, and she said it was cruel of him.

“You don’t mean that, Grizel.”

“Don’t I?” She was delighted that he knew it.

“No; you mean that you like me to be sure of it.”

“But I want to be sure of it myself.” “You are. That was why you asked me if I loved you. Had you not been sure of it you would not have asked.”

“How clever you are!” she said gleefully, and caressed a button of his velvet coat. “But you don’t know what that means! It does not mean that I love you—not merely that.”

“No; it means that you are glad I know you so well. It is an ecstasy to you, is it not, to feel that I know you so well?”

“It is sweet,” she said. She asked curiously: “What did you do last night, after you left me? I can’t guess, though I daresay you can guess what I did.”

“You put the glove under your pillow, Grizel.” (She had got the precious glove.)

“However could you guess!”

“It has often lain under my own.”

“Oh!” said Grizel, breathless.

“Could you not guess even that?”

“I wanted to be sure. Did it do anything strange when you had it there?”

“I used to hear its heart beating.”

“Yes, exactly! But this is still more remarkable. I put it away at last in my sweetest drawer, and when I woke in the morning it was under my pillow again. You could never have guessed that.”

“Easily. It often did the same thing with me.” “Story-teller! But what did you do when you went home?”

He could not have answered that exhaustively, even if he would, for his actions had been as contradictory as his emotions. He had feared even while he exulted, and exulted when plunged deep in fears. There had been quite a procession of Tommies all through the night; one of them had been a very miserable man, and the only thing he had been sure of was that he must be true to Grizel. But in so far as he did answer he told the truth.

“I went for a stroll among the stars,” he said. “I don’t know when I got to bed. I have found a way of reaching the stars. I have to say only, ‘Grizel loves me,’ and I am there.”

“Without me!”

“I took you with me.”

“What did we see? What did we do?”

“You spoiled everything by thinking the stars were badly managed. You wanted to take the supreme control. They turned you out.”

“And when we got back to earth?”

“Then I happened to catch sight of myself in a looking-glass, and I was scared. I did not see how you could possibly love me. A terror came over me that in the Den you must have mistaken me for someone else. It was a darkish night, you know.” “You are wanting me to say you are handsome.”

“No, no; I am wanting you to say I am very, very handsome. Tell me you love me, Grizel, because I am beautiful.”

“Perhaps,” she replied, “I love you because your book is beautiful.”

“Then good-bye for ever,” he said sternly.

“Would not that please you?”

“It would break my heart.”

“But I thought all authors—”

“It is the commonest mistake in the world. We are simple creatures, Grizel, and yearn to be loved for our face alone.”

“But I do love the book,” she said, when they became more serious, “because it is part of you.”

“Rather that,” he told her, “than that you should love me because I am part of it. But it is only a little part of me, Grizel; only the best part. It is Tommy on tiptoes. The other part, the part that does not deserve your love, is what needs it most.”

“I am so glad!” she said eagerly. “I want to think you need me.”

“How I need you!”

“Yes, I think you do—I am sure you do; and it makes me so happy.”

“Ah,” he said, “now I know why Grizel loves me.” And perhaps he did know now. She loved to think that she was more to him than the new book, but was not always sure of it; and sometimes this saddened her, and again she decided that it was right and fitting. She would hasten to him to say that this saddened her. She would go just as impulsively to say that she thought it right.

Her discoveries about herself were many.

“What is it to-day?” he would say, smiling fondly at her. “I see it is something dreadful by your face.”

“It is something that struck me suddenly when I was thinking of you, and I don’t know whether to be glad or sorry.”

“Then be glad, you child.”

“It is this: I used to think a good deal of myself; the people here thought me haughty; they said I had a proud walk.”

“You have it still,” he assured her; the vitality in her as she moved was ever a delicious thing to him to look upon.

“Yes, I feel I have,” she admitted, “but that is only because I am yours; and it used to be because I was nobody’s!”

“Do you expect my face to fall at that?”

“No, but I thought so much of myself once, and now I am nobody at all. At first it distressed me, and then I was glad, for it makes you everything and me nothing. Yes, I am glad, but I am just a little bit sorry that I should be so glad!” “Poor Grizel!” said he.

“Poor Grizel!” she echoed. “You are not angry with me, are you, for being almost sorry for her? She used to be so different. ‘Where is your independence, Grizel?’ I say to her, and she shakes her sorrowful head. The little girl I used to be need not look for me any more; if we were to meet in the Den she would not know me now.”

Ah, if only Tommy could have loved in this way! He would have done it if he could. If we could love by trying, no one would ever have been more loved than Grizel. “Am I to be condemned because I cannot?” he sometimes said to himself in terrible anguish; for though pretty thoughts came to him to say to her when she was with him, he suffered anguish for her when he was alone. He knew it was tragic that such love as hers should be given to him, but what more could he do than he was doing?