Arthur Orton : Famous Impostors by Bram Stoker

Famous Impostors : The Tichborne Claimant Arthur Orton

by

Bram Stoker

Arthur Orton

(The Tichborne Claimant.)

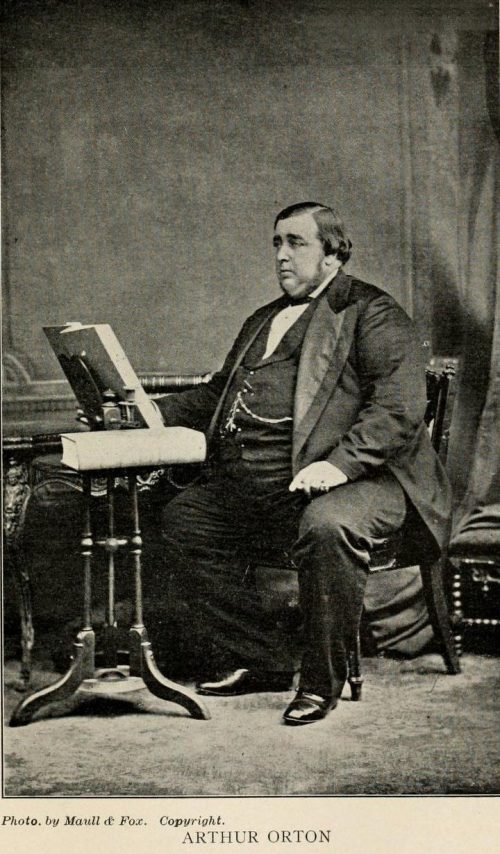

In the annals of crime, Arthur Orton, the notorious claimant to the rich estates and title of Tichborne, takes a foremost place; not only as the originator of one of the most colossal attempts at fraud on record, but also from his remarkable success in duping the public. It would be difficult indeed to furnish a more striking example of the height to which the blind credulity of people will occasionally attain. Of pretenders, who by pertinacious and unscrupulous lying have sought to bolster up fictitious claims, there have been many before Orton; but he certainly surpassed all his predecessors in working out the lie circumstantial in such a way as to divide the country for years into two great parties—those who believed in the Claimant, and those who did not. Over one hundred persons, drawn from every class, and for the most part honest in their belief, swore to the identity of this illiterate butcher’s son—this stockman, mail-rider and probably bushranger and thief—as the long-lost son and heir of the ancient house of Tichborne of Titchborne. To gain his own selfish ends this individual was ready to rob a gentlewoman of her fair fame, to destroy the peace of a great family who, to free themselves from a persecution, as cruel as it was vicious, had to be pilloried before a ruthless and unsympathising mob, to have the privacy of their home invaded, and to hear their women’s names banded from one coarse mouth to another. Thus, and through no fault of their own, they were compelled to endure a mental torture far worse than any physical suffering, besides having to expend vast sums of money, as well as time and labour, in order to protect themselves from the would-be depredations of an unscrupulous adventurer. It has been estimated that the resistance of this fictitious claim cost the Tichborne estate not far short of one hundred thousand pounds.

The baronetcy of Tichborne, now Doughty-Tichborne, is one of the oldest. It has been claimed that the family held possession of the Manor of Tichborne for two hundred years before the Conquest. Be this as it may—and, in the light of J. H. Round’s revelations, some scepticism as to these pre-Norman pedigrees is permissible—their ancestors may be traced back to one Walter de Tichborne who held the manor, from which he took his name, as early as 1135. Their names too, are interwoven with the history of the country. Sir Benjamin, the first baronet—for the earlier de Tichbornes were knights,—as Sheriff of Southhampton, on the death of Queen Elizabeth, repaired instantly to Winchester and on his own initiative proclaimed the accession of James VI of Scotland as King of England, for which service he was made a baronet, and his four sons received the honour of knighthood. His successor, Sir Richard, was a zealous supporter of the Royal cause during the civil wars. Sir Henry, the third baronet, hazarded his life in the defence of Charles I and had his estates sequestered by the Parliamentarians though he was recompensed at the Restoration.

Believers in occultism might see in the trials and tribulations brought down upon the unfortunate heads of the Tichborne family by the machinations of the Claimant, the realisation of the doom pronounced by a certain Dame Ticheborne away back in the days of Henry II.

Sir Roger de Ticheborne of those days married Mabell, the daughter and heiress of Ralph de Lamerston, of Lamerston, in the Isle of Wight, by whom he acquired that estate. This good wife played the part of lady bountiful of the neighbourhood. After a life spent in acts of charity and goodness, as her end drew nigh and she lay on her death bed, her thoughts went out to her beloved poor. She begged her husband, that in order to have her memory kept green the countryside round, he would grant a bequest sufficient to ensure, once a year, a dole of bread to all comers to the gates of Tichborne. To gratify her whim Sir Roger promised her as much land as she could encompass while a brand plucked from the fire should continue to burn. As the poor lady had been bedridden for years her husband may have had no idea that she could, even if she would, take his promise seriously. However, the venerable dame, after being carried out upon the ground, seemed to regain her strength in a miraculous fashion, and, to the surprise of all, managed to crawl round several rich and goodly acres which to this day are known as “the Crawls.”

Carried to her bed again after making this last supreme effort and summoning her family to her bedside, Lady Ticheborne predicted with her dying breath, that, as long as this annual dole was continued, so long should the house of Tichborne prosper; but, should it be neglected, their fortunes would fail and the family name become extinct from want of male issue. As a sure sign by which these disasters might be looked for, she foretold that a generation of seven sons would be immediately followed by one of seven daughters.

The benevolent custom thus established was faithfully observed for centuries. On every Lady Day crowds of humble folk came from near and far to partake of the famous dole which consisted of hundreds of small loaves. But ultimately the occasion degenerated into a noisy merry-making, a sort of fair, until it was finally discontinued in 1796, owing to the complaints of the magistrates and local gentry that the practice encouraged vagabonds, gipsies and idlers of all sorts to swarm into the neighbourhood under pretence of receiving the dole.

Strangely enough Sir Henry Tichborne, the baronet of that day (the original name of de Ticheborne had by this time been reduced to Tichborne), had seven sons, while his eldest son who succeeded him in 1821, had seven daughters. The extinction of the family name, too, came to pass, for in the absence of male issue, Sir Henry, the eighth baronet, was succeeded by his brother, who had taken the surname of Doughty on coming into the estates bequeathed to him on these terms, by a distant relative, Miss Doughty; though, in after years, his brother, who in turn succeeded him, obtained the royal licence to couple the old family name with that of Doughty. Following this repeated lapse of direct male heirs came other troubles; but it is to be hoped that the successful defeat of the fraudulent claim of Arthur Orton set a period to the doom pronounced long years ago by the Lady Mabell.

Most families, great and small, have their secret troubles and unpleasantness, and the Tichbornes seem to have had their share of them. To this may be traced the actual, if remote, cause of the Claimant’s imposture. James Tichborne, afterwards the tenth baronet, the father of the missing Roger, who was drowned in the mysterious loss of the Bella, off the coast of South America, in the spring of 1854, lived abroad for many years; but, while his wife was French in every sentiment, he himself from time to time exhibited a keen desire to return to his native land. When Roger was born there was small likelihood of his ever succeeding to either title or estates, and so his education was almost entirely a foreign one.

Sir Henry Tichborne, who had succeeded in 1821, though blessed with seven beautiful daughters, had no son. Still there was their uncle Edward, who had taken the name of Doughty, and he, after Sir Henry, was the next heir. Edward, too, had a son and daughter. But, one day, news came to James and his wife, in France, that their little nephew was dead; and with the possibilities which this change opened up, it brought home to the father the error he had committed in permitting Roger to grow up ignorant of the English tongue and habits. It was manifest that Mr. James F. Tichborne was not unlikely to become the next baronet, and he felt it his bounden duty to make good his previous neglect, by providing his son with an English education, such as would fit him for his probable position as head of the house of Tichborne. In this praiseworthy intention he met with strong opposition from his wife whose great aim it was to see her son grow up a Frenchman. To her, France was the only land worth living in. She cared nought for family traditions; her dream was that her darling boy should marry into some distinguished family in France or Italy. If he was to enter the army, then it should be in some foreign service. But to England he should not go if she could prevent it.

James Tichborne, like many weak men with self-willed wives, put off the inevitable day as long as he could; and in the end only achieved his purpose by strategy. Roger was sixteen years of age when news arrived of the death of Sir Henry. Naturally James arranged to be present at his brother’s funeral and it was only reasonable that he should be accompanied by his son Roger, whom everyone now regarded as the heir. Accordingly the boy took leave of his mother, but under the solemn injunction to return quickly. However, his father had determined otherwise. After attending the funeral of his uncle, at the old chapel at Tichborne, Roger was, by the advice of relatives and friends, and with the consent of the boy himself, taken down to the Jesuit College at Stonyhurst. When Mrs. Tichborne learned of this step, her fury knew no bounds. She upbraided her husband violently; and there was a renewal of the old scenes in the Tichborne establishment. Roger wrote his mother filial, if ill-spelt, letters in French; but, for a year, the son, though ardently looking for a letter, got no token of affection from the incensed and indignant lady.

During his three years’ stay at Stonyhurst, Roger seems to have applied himself diligently to the study of English; but, though he made fair progress, he was never able to speak it with as much purity and command of words as when conversing in French. In Latin, mathematics, and chemistry, too, he contrived to make fair headway; while his letters evidenced an inclination for the study of polite literature. If not highly accomplished, he was of a refined and sensitive nature. During this period he made many friends, spending his vacation with his English relatives in turn. His great delight was to stay at Tichborne, then in possession of his father’s brother, Sir Edward Doughty. Withal, the shy, pale-faced boy steadily gained in favour, for he had a nature which disarmed ill-feeling. As time wore on it became necessary to determine on some profession for the lad; and needless to say his father’s choice of the army added fuel to the fire of his wife’s anger. After some delay a commission was obtained and Mr. Roger Charles Tichborne was gazetted a coronet in the Sixth Dragoons, better known as the Carbineers.

Defeated in her purpose of making a Frenchman of her boy, Roger’s mother yet continued to harp upon her old desire to marry him to one of the Italian princesses of whom he had heard so much. But Roger had other ideas, for he had fallen passionately in love with his cousin—Miss Katharine Doughty afterwards Lady Radcliffe. However, the course of love was not to run smooth. The Tichbornes had always been Roman Catholic, and the marriage of first cousins was discountenanced by that church. Consequently when some little token incidentally revealed to the father the secret and yet unspoken love of the young people, their dream was rudely shattered.

That the girl warmly reciprocated her cousin’s affection was beyond question, and Lady Doughty was certainly sympathetic though she took exception to certain of her nephew’s habits. He was an inveterate smoker besides drinking too freely. These and other little failings seem to have aroused some fear in her anxious mother’s heart, though she quite recognised the boy’s kind disposition, and the fact that he was truthful, honourable and scrupulous in points of duty. Still she would not oppose the wishes of the young lovers—except to the extent of pleading and encouraging Roger to master his weaknesses. It was Christmas time in 1851 when the dénoument came and the eyes of Sir Edward were opened to what was going on. He was both vexed and angry, and was resolved that the engagement should be broken off before it grew more serious. One last interview was permitted to the cousins and, this over, the young man was to leave the house forever. The great hope of his life extinguished, there was nothing left for Roger but to rejoin his regiment, then expecting orders for India, and to endeavour to forget the past. Still even in those dark days neither Roger nor Kate quite gave up hope of some change. Lady Doughty, despite her dread of her nephew’s habits, had a warm regard for him, and could be relied upon to plead his cause; and in a short time circumstances unexpectedly favoured him. Sir Edward was ill and, fearing that death was approaching, he sent for his nephew and revived the subject. He explained that if it were not for the close relationship he should have no objection to the marriage and begged Roger to wait for three years. If then the affection, one for the other, remained unaltered, and providing that Roger obtained his own father’s consent and that of the Church, he would accept things as the will of God and agree to the union. As might be expected, Roger gratefully promised loyally to observe the sick man’s wishes.

However, Sir Edward, instead of dying, slowly mended, and Roger returned to his regiment. Occasionally he would spend his leave with his aunt and uncle, when the young people loved to walk together in the beautiful gardens of Tichborne exchanging sweet confidences and weaving plans for the future. On what proved to be his last visit to his ancestral home, in the midsummer of 1852, Roger, to comfort his cousin, confided a secret to her—a copy of a vow, which he had written out and signed, solemnly pledging himself, in the event of their being married before three years had passed, to build a church or chapel at Tichborne as a thanks offering to the Holy Virgin for the protection shown by her in praying God that their wishes might be fulfilled.

His leave up, Roger went back to his regiment more than ever a prey to his habitual melancholy. To his great regret the orders for the Carbineers to go to India were countermanded. He accordingly determined to throw up his commission and travel abroad until his period of probation had passed. South America had long been the subject of his dreams, and so thither he would make his way; and in travelling through that vast continent he hoped to find occupation for his mind and so get through the trying period of waiting. His plan was to spend a year in Chili, Guayaquil and Peru, and thence to visit Mexico, and so, by way of the United States, to return home. Having come to this resolution he lost no time in putting it into execution. Being of business-like habits he made his will, in which he purposely omitted any mention of the “church or chapel.” This secret had already been committed to paper, and with other precious souvenirs of his love for his cousin, had been confided to his most trusted friend—Mr. Gosford, the steward of the family estate. After paying a round of farewell visits to his parents and old friends in Paris, Roger finally set sail from Havre, on March 21, 1853, in a French vessel named La Pauline, for Valparaiso, at which port she arrived on the 19th of the following June, when Roger set out on his wanderings. During his travels Roger continued to write home regularly; but the first news he received was bad. Sir Edward Doughty had died almost before the Pauline had lost sight of the English shores; and Roger’s father and mother were now Sir James and Lady Tichborne.

Presently the wanderer began to retrace his steps, making his way to Rio de Janeiro. Here, he found a vessel called the Bella hailing from Liverpool, about to sail for Kingston, Jamaica, and as he had directed his letters and remittances to be forwarded there, he prevailed upon the captain to give him a passage. On the 20th of April, 1854, the Bella passed from the port of Rio into the ocean. From that day no one ever set eyes upon her. Six days after she left harbour, a ship traversing her path found, amongst other ominous tokens of a wreck, a capsized long-boat bearing the name “Bella, Liverpool.”

These were taken into Rio and forthwith the authorities caused the neighbouring seas to be scoured in quest of survivors; but none were ever found. That the Bella had foundered there was little room to doubt. It was supposed that she had been caught in a sudden squall, that her cargo had shifted, and that, unable to right herself, the vessel had gone down in deep water, giving but little warning to those on board. In a few months the sad news reached Tichborne, where the absence of letters from the previously diligent correspondent had already raised grave fears. The sorrow-stricken father caused enquiries to be made in America and elsewhere. For a time, there was a faint hope that some one aboard the Bella might have been picked up by some passing vessel; but, as months wore on, even these small hopes dwindled away. The letters which poor Roger had so anxiously asked might be directed to him at the post office, Kingston, Jamaica, remained there till the ink grew faded; the banker’s bill which lay at the agents’ remained unclaimed. At last the unfortunate vessel was finally written off at Lloyd’s as lost, the insurance money paid, and gradually the Bella faded from the memories of all but those who had lost friends or relatives in her. Lady Tichborne alone, refused to abandon hope.

Her obstinate disregard of such conclusive evidence of the fate of her unfortunate son preyed upon her mind to such an extent as to make her an easy victim for any scheming rascal pretending to have news of her lost son; and “sailors,” who told all sorts of wild stories of how some of the survivors of the Bella had been rescued and landed in a foreign port, became constant visitors at Tichborne Park and profited handsomely from the weak-minded lady’s credulity. Sir James, himself, made short work of these tramping “sailors,” but after his death, in 1862, the lady became even more ready to be victimised by their specious lies.

Firm in her belief that Roger was still alive, Lady Tichborne now caused advertisements to be inserted in numerous papers; and in November, 1865, she learnt through an agency in Sydney that a man answering the description of her son had been found in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales. A long correspondence ensued, the tone and character of which ought to have put her on her guard; but, over-anxious to believe that she had indeed found her long-lost son, any wavering doubts she may have had, were swept from her mind by the evidence of an aged negro servant named Boyle, an old pensioner of the Tichborne family. Boyle, who lived in New South Wales, professed to recognise the Claimant as his dear young master, and he certainly remained one of his most devoted adherents to the end. Undoubtedly this man’s simplicity proved a very valuable asset to Orton. His intimate knowledge of the arrangements of Tichborne Park was pumped dry by his new master, who, aided by a most tenacious memory, was afterwards able to use the information thus obtained with startling effect.

As to the identity of the Claimant with Arthur Orton there can be absolutely no doubt. As a result of the enquiries made by the trustees of the Tichborne estate nearly the whole of his history was unmasked. He was born, in 1834, at Wapping where his father kept a butcher’s shop. In 1848 he took passage to Valparaiso, whence he made his way up country to Melipilla. Here he stayed some eighteen months receiving much kindness from a family named Castro, and it was their name he went under at Wagga Wagga. In 1851 he returned home and entering his father’s business became an expert slaughterman. The following year he emigrated to Australia; but after the spring of 1854 he ceased to correspond with his family. He had evidently led a life of hardship and adventure—probably not unattended with crime, and certainly with poverty. At Wagga Wagga he carried on a small butcher’s business, and it was from here that he got into communication with Lady Tichborne just after his marriage to an illiterate servant girl.

According to his subsequent confession, until his attention was drawn to the advertisement for the missing Roger, he had never even heard of the name of Tichborne, and it was only his success when, by way of a joke upon a chum, he claimed to be the missing baronet, that led him to pursue the matter in sober earnest. Indeed he seemed at first very reluctant to leave Australia, and probably he was only driven to accede to Lady Tichborne’s request, to return “home” at once, by the fact that he had raised large sums of money on his expectations. His original intention was probably to obtain some sort of recognition, and then to return to Australia with whatever money he had succeeded in collecting.

After wasting much time he left Australia and arrived in England, by a very circuitous route, on Christmas Day, 1866. His first step on landing, it was subsequently discovered, was to make a mysterious visit to Wapping. His parents were dead, but his enquiries showed a knowledge, both of the Orton family and the locality, which was afterwards used against him with very damaging effect. His next proceeding was to make a flying and surreptitious excursion to Tichborne House, where, as far as possible, he acquainted himself with the bearings of the place. In this he was greatly assisted by one Rous, a former clerk to the old Tichborne attorney, who was then keeping a public house in the place. From this man, who became his staunch ally, he had no doubt acquired much useful information; and it is significant that he sedulously kept clear of Mr. Gosford, the agent to whom the real Roger had confided his sealed packet before leaving England.

Lady Tichborne was living in Paris at this time and it was here, in his hotel bedroom, on a dark January afternoon, that their first interview took place for, curiously enough, the gentleman was too ill to leave his bed! The deluded woman professed to recognise him at once. As she sat beside his bed, “Roger” keeping his face turned to the wall, the conversation took a wide range, the sick man showing himself strangely astray. He talked to her of his grandfather, whom the real Roger had never seen; he said he had served in the ranks; referred to Stonyhurst as Winchester; spoke of his suffering as a lad from St. Vitus’s dance—a complaint which first led to young Arthur Orton being sent on a sea voyage; but did not speak of the rheumatism from which Roger had suffered. But it was all one to the infatuated woman—”He confuses everything as if in a dream,” she wrote in exculpating him; but unsatisfactory as this identification was, she never departed from her belief. She lived under the same roof with him for weeks, accepted his wife and children, and allowed him £1,000 a year. It did not weigh with her that the rest of the family unanimously declared him to be an impostor, or that he failed to recognise them or to recall any incident in Roger’s life.

Nearly four years elapsed before the Claimant commenced his suit of ejectment against the trustees of the infant Sir Alfred Tichborne—the posthumous son of Roger’s younger brother; but he utilised the time to good purpose. He had taken into his service a couple of old Carbineers who had been Roger’s servants and before long so completely mastered small details of regimental life that some thirty of Roger’s old brother-officers and men were convinced of his identity. He went everywhere, called upon all Roger’s old friends, visited the Carbineers’ mess and generally left no stone unturned to get together evidence in support of his identity. As a result of his strenuous activity and plausibility he produced at the first trial over one hundred witnesses who, on oath, identified him as Roger Tichborne; and these witnesses included Lady Tichborne, the family solicitor, magistrates, officers and men from Roger’s old regiment besides various Tichborne tenants and friends of the family. On the other hand, there were only seventeen witnesses arraigned against him; and, in his own opinion, it was his own evidence that lost him the case. He would have won, he said, “if only he could have kept his mouth shut.”

The trial of this action lasted 102 days. Sergeant Ballantine led for the Claimant; and Sir John Coleridge (afterwards Lord Chief-justice), and Mr. Hawkins, Q. C. (afterwards Lord Brampton), for the trustees of the estates of Tichborne. The cross-examination of the Claimant at the hands of Sir John Coleridge lasted twenty-two days, during which the colossal ignorance he displayed was only equalled by his boldness, dexterity and the bull-dog tenacity with which he faced the ordeal. To quote Sir John’s own words: “The first sixteen years of his life he has absolutely forgotten; the few facts he had told the jury were already proved, or would hereafter be shown, to be absolutely false and fabricated. Of his college life he could recollect nothing. About his amusements, his books, his music, his games, he could tell nothing. Not a word of his family, of the people with whom he lived, their habits, their persons, their very names. He had forgotten his mother’s maiden name; he was ignorant of all particulars of the family estate; he remembered nothing of Stonyhurst; and in military matters he was equally deficient. Roger, born and educated in France, spoke and wrote French like a native and his favourite reading was French literature; but the Claimant knew nothing of French. Of the ‘sealed’ packet he knew nothing and, when pressed, his interpretation of its contents contained the foulest and blackest calumny of the cousin whom Roger had so fondly loved. This was proved by Mr. Gosford, to whom the packet had been originally entrusted, and by the production of the duplicate which Roger had given to Miss Doughty herself. The physical discrepancy, too, was no less remarkable; for, while Roger, who took after his mother was slight and delicate, with narrow sloping shoulders, a long narrow face and thin straight dark hair, the Claimant was of enormous bulk, scaling over twenty-four stone, big-framed and burly, with a large round face and an abundance of fair and rather wavy hair. And yet, curiously enough, the Claimant undoubtedly possessed a strong likeness to several male members of the Tichborne family.”

When questioned as to the impressive episode of Roger’s love for his cousin, the Claimant showed himself hopelessly at sea. His answers were confused and irreconcilable. Not only could he give no precise dates, but even the broad outline of the story was beyond him. Yet, for good reasons, the Solicitor-General persisted in pressing him as to the contents of the sealed packet and compelled him to repeat the slanderous version of the incident which he had long ago given when interrogated on the point. Mrs. Radcliffe (she was not then Lady) sat in court beside her husband, and thus had the satisfaction of seeing the infamous charges brought against the fair fame of her girlhood recoil on the head of the wretch who had resorted to such villainous devices. Unfortunately, some years after Roger’s disappearance, Mr. Gosford, feeling that he was neither justified in keeping the precious packet, nor in handing it to any other person, had burnt it; but, fortunately his testimony as to its contents was proved in the most complete manner by the production of the duplicate which poor Roger had given to his cousin on his last visit to Tichborne.

Where the case broke down most completely was in the matter of tattoo marks. Roger had been freely tattooed. Among other marks he bore, on his left arm, a cross, an anchor, and a heart which was testified to by the persons who had pricked them in. Orton, too, it was found out, had also been tattooed on his left arm with his initials, “A. O.,” and, though neither remained, there was a mark which was sworn to be the obliteration of those letters. Small wonder then that, on the top of this damning piece of evidence, the jury declared they required to hear nothing further, upon which the Claimant’s counsel, to avoid the inevitable verdict for their opponents, elected to be nonsuited. But these tactics did not save their client, for he was at once arrested, on the judge’s warrant, on the charge of wilful and corrupt perjury, and committed to Newgate where he remained until bail for £10,000 was forthcoming.

A year later, on April 23, 1873, the Claimant was arraigned before a special jury in the Court of Queen’s Bench. The proceedings were of a most prolix and unusual character. Practically the same ground was covered as in the civil trial, only the process was reversed: the Claimant having now to defend instead of to attack. Many of the better-class witnesses, including the majority of Roger’s brother-officers, now forsook the Claimant. There was a deal of cross-swearing. The climax of the long trial was the production by the defence of a witness to support the Claimant’s account of his wreck and rescue. This was a man who called himself Jean Luie and claimed to be a Danish seaman. With a wealth of picturesque detail he told how he was one of the crew of the Osprey which had picked up a boat of the shipwrecked Bella, in which was the claimant and some of the crew, and how when the Osprey arrived at Melbourne, in the height of the gold fever, every man of the crew from the captain downwards had deserted the ship and gone up country. According to his story from that time forth he had seen nothing of any of the castaways; but having come to England in search of his wife he had heard of the trial. When Luie was first brought into the presence of the Claimant that astute person immediately claimed him with the greeting in Spanish “Como esta, Luie?“—”How are you, Luie?” The sailor with equal readiness recognised Orton as the man he had helped to rescue years before. All this sounded very convincing; but it would not stand investigation. From the beginning to end the thing was an invention; an examination of shipping records failed to find the Osprey so that she must have escaped the notice of the authorities in every port she had entered from the day she was launched! Of “Sailor” Luie, however, a very complete record was established. Not only were the police able to prove that, at the time he swore he was a seaman on board the Osprey, he was actually employed by a firm at Hull; that he had never been a seaman at all; but that he was a well-known habitual criminal and convict only recently released on a ticket-of-leave. This made things very awkward for the defence who made every effort to shake free from the taint of such perjured evidence. Dr. Kenealy, seeing his dilemma, contended that it had been concocted by Luie himself. But the damning and unanswerable fact remained—that, by his recognition of the man, the Claimant had acknowledged a previous acquaintance with him which he could only have had by being privy to the fraud.

On February 28, 1874, the one hundred and eighty-eighth day of the trial, the jury after half-an-hour’s deliberation returned their verdict. They found that the defendant was not Roger Charles Tichborne; that he was Arthur Orton; and finally that the charges made against Miss Catherine Doughty were not supported by the slightest evidence. Orton was sentenced to fourteen years’ penal servitude which, assuredly, was none too heavy for offences so enormous. The trial was remarkable, not only for its inordinate length, but also for the extraordinary scenes by which it was characterised and for which Dr. Kenealy, leading counsel for the defence, was primarily responsible. His conduct was sternly denounced by the Lord Chief Justice in his summing up as: “the torrent of undisguised and unlimited abuse in which the learned counsel for the defence has thought fit to indulge,” and he declared that “there never was in the history of jurisprudence a case in which such an amount of imputation and invective had been used before.” After the trial was over, Dr. Kenealy tried to turn the case into a national question through the medium of a virulent paper he started with the title of the Englishman; and undeterred by being disbarred for his flagrant breaches of professional etiquette, he went about the country delivering the most extravagant speeches concerning the trial. He was elected Member of Parliament for Stoke, and, on April 23, 1875, moved for a royal commission of inquiry into the conduct of the Tichborne Case; but his motion was defeated by 433 votes to 1.

The verdict and sentence created enormous excitement throughout the country, for all classes, more or less, had subscribed to the defence fund. But, by the time Orton was released, in 1884, practically all interest had died away, and his effort to resuscitate it was a miserable failure. In the sworn confession which he published in the People, in 1895, he told the whole story of the fraud from its inception to its final denouement. Orton survived his release from prison for fourteen years, but gradually sinking into poverty, he died in obscure lodgings in Shouldham Street, Marylebone, on April 1, 1898. To the end he was a fraud and impostor for, before his death, he is said to have recanted his sworn confession, which nevertheless bore the stamp of truth and was in perfect accord with the information obtained by the prosecution, while his coffin bore the lying inscription: “Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne; born 5th January, 1829; died 1st April, 1898.”

Famous Impostors

Chapter I. Pretenders

A. Perkin Warbeck

B. The Hidden King

C. Stephan Mali

D. The False Dauphins

E. Princess Olive

Chapter II. Practitioners of Magic

A. Paracelsus

B. Cagliostro

C. Mesmer

Chapter III.

The Wandering Jew

Chapter IV.

John Law

Chapter V. Witchcraft and Clairvoyance

A. Witches

B. Doctor Dee

C. La Voisin

D. Sir Edward Kelley

E. Mother Damnable

F. Matthew Hopkins

Chapter VI.

Arthur Orton (Tichborne claimant)

Chapter VII. Women as Men

A. The Motive for Disguise

B. Hannah Snell

C. La Maupin

D. Mary East

Chapter VIII. Hoaxes, etc.

A. Two London Hoaxes

B. The Cat Hoax

C. The Military Review

D. The Toll-Gate

E. The Marriage Hoax

F. Buried Treasure

G. Dean Swift’s Hoax

H. Hoaxed Burglars

I. Bogus Sausages

J. The Moon Hoax

Chapter IX.

Chevalier d’Eon

Chapter X.

The Bisley Boy