Sylvie and Bruno by Lewis Carroll

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter I. Less Bread! More Taxes!

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter II. L’Amie Inconnue

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter III. Birthday-Presents

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter IV. A Cunning Conspiracy

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter V. A Beggar’s Palace

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VI. The Magic Locket

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VII. The Baron’s Embassy

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VIII. A Ride on A Lion

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter IX. A Jester and A Bear

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter X. The Other Professor

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XI. Peter and Paul

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XII. A Musical Gardener

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIII. A Visit to Dogland

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIV. Fairy-Sylvie

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XV. Bruno’s Revenge

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVI. A Changed Crocodile

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVII. The Three Badgers

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVIII. Queer Street, Number Forty

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIX. How to Make A Phlizz

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XX. Light Come, Light Go

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXI. Through the Ivory Door

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXII. Crossing the Line

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXIII. An Outlandish Watch

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXIV. The Frogs’ Birthday-Treat

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXV. Looking Eastward

Lewis Carroll – Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIII. A Visit to Dogland

“There’s a house, away there to the left,” said Sylvie, after we had walked what seemed to me about fifty miles. “Let’s go and ask for a night’s lodging.”

“It looks a very comfable house,” Bruno said, as we turned into the road leading up to it. “I doos hope the Dogs will be kind to us, I is so tired and hungry!”

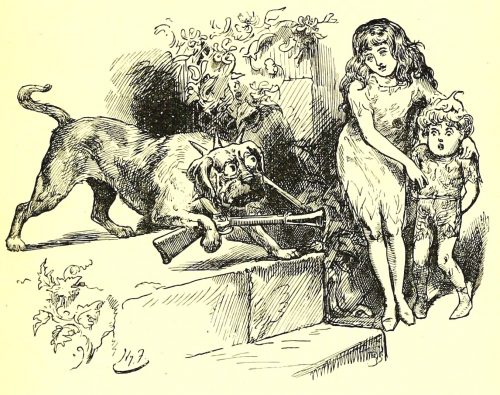

A Mastiff, dressed in a scarlet collar, and carrying a musket, was pacing up and down, like a sentinel, in front of the entrance. He started, on catching sight of the children, and came forwards to meet them, keeping his musket pointed straight at Bruno, who stood quite still, though he turned pale and kept tight hold of Sylvie’s hand, while the Sentinel walked solemnly round and round them, and looked at them from all points of view.

“Oobooh, hooh boohooyah!” He growled at last. “Woobah yahwah oobooh! Bow wahbah woobooyah? Bow wow?” he asked Bruno, severely.

Of course Bruno understood all this, easily enough. All Fairies understand Doggee—that is, Dog-language. But, as you may find it a little difficult, just at first, I had better put it into English for you. “Humans, I verily believe! A couple of stray Humans! What Dog do you belong to? What do you want?”

“We don’t belong to a Dog!” Bruno began, in Doggee. (“Peoples never belongs to Dogs!” he whispered to Sylvie.)

But Sylvie hastily checked him, for fear of hurting the Mastiff’s feelings. “Please, we want a little food, and a night’s lodging—if there’s room in the house,” she added timidly. Sylvie spoke Doggee very prettily: but I think it’s almost better, for you, to give the conversation in English.

“The house, indeed!” growled the Sentinel. “Have you never seen a Palace in your life? Come along with me! His Majesty must settle what’s to be done with you.”

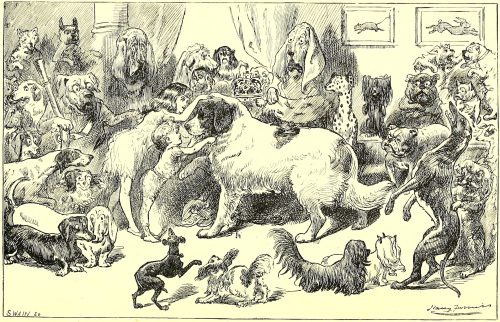

They followed him through the entrance-hall, down a long passage, and into a magnificent Saloon, around which were grouped dogs of all sorts and sizes. Two splendid Blood-hounds were solemnly sitting up, one on each side of the crown-bearer. Two or three Bull-dogs—whom I guessed to be the Body-Guard of the King—were waiting in grim silence: in fact the only voices at all plainly audible were those of two little dogs, who had mounted a settee, and were holding a lively discussion that looked very like a quarrel.

“Lords and Ladies in Waiting, and various Court Officials,” our guide gruffly remarked, as he led us in. Of me the Courtiers took no notice whatever: but Sylvie and Bruno were the subject of many inquisitive looks, and many whispered remarks, of which I only distinctly caught one—made by a sly-looking Dachshund to his friend—”Bah wooh wahyah hoobah Oobooh, hah bah?” (“She’s not such a bad-looking Human, is she?”)

Leaving the new arrivals in the centre of the Saloon, the Sentinel advanced to a door, at the further end of it, which bore an inscription, painted on it in Doggee, “Royal Kennel—Scratch and Yell.”

Before doing this, the Sentinel turned to the children, and said “Give me your names.”

“We’d rather not!” Bruno exclaimed, pulling Sylvie away from the door. “We want them ourselves. Come back, Sylvie! Come quick!”

“Nonsense!” said Sylvie very decidedly: and gave their names in Doggee.

Then the Sentinel scratched violently at the door, and gave a yell that made Bruno shiver from head to foot.

“Hooyah wah!” said a deep voice inside. (That’s Doggee for “Come in!”)

“It’s the King himself!” the Mastiff whispered in an awestruck tone. “Take off your wigs, and lay them humbly at his paws.” (What we should call “at his feet.”)

Sylvie was just going to explain, very politely, that really they couldn’t perform that ceremony, because their wigs wouldn’t come off, when the door of the Royal Kennel opened, and an enormous Newfoundland Dog put his head out. “Bow wow?” was his first question.

“When His Majesty speaks to you,” the Sentinel hastily whispered to Bruno, “you should prick up your ears!”

Bruno looked doubtfully at Sylvie. “I’d rather not, please,” he said. “It would hurt.”

“It doesn’t hurt a bit!” the Sentinel said with some indignation. “Look! It’s like this!” And he pricked up his ears like two railway signals.

Sylvie gently explained matters. “I’m afraid we ca’n’t manage it,” she said in a low voice. “I’m very sorry: but our ears haven’t got the right—” she wanted to say “machinery” in Doggee: but she had forgotten the word, and could only think of “steam-engine.”

The Sentinel repeated Sylvie’s explanation to the King.

“Can’t prick up their ears without a steam-engine!” His Majesty exclaimed. “They must be curious creatures! I must have a look at them!” And he came out of his Kennel, and walked solemnly up to the children.

What was the amazement—not to say the horror—of the whole assembly, when Sylvie actually patted His Majesty on the head, while Bruno seized his long ears and pretended to tie them together under his chin!

The Sentinel groaned aloud: a beautiful Greyhound—who appeared to be one of the Ladies in Waiting—fainted away: and all the other Courtiers hastily drew back, and left plenty of room for the huge Newfoundland to spring upon the audacious strangers, and tear them limb from limb.

Only—he didn’t. On the contrary his Majesty actually smiled—so far as a Dog can smile—and (the other Dogs couldn’t believe their eyes, but it was true, all the same) his Majesty wagged his tail!

“Yah! Hooh hahwooh!” (that is “Well! I never!”) was the universal cry.

His Majesty looked round him severely, and gave a slight growl, which produced instant silence. “Conduct my friends to the banqueting-hall!” he said, laying such an emphasis on “my friends” that several of the dogs rolled over helplessly on their backs and began to lick Bruno’s feet.

A procession was formed, but I only ventured to follow as far as the door of the banqueting-hall, so furious was the uproar of barking dogs within. So I sat down by the King, who seemed to have gone to sleep, and waited till the children returned to say good-night, when His Majesty got up and shook himself.

“Time for bed!” he said with a sleepy yawn. “The attendants will show you your room,” he added, aside, to Sylvie and Bruno. “Bring lights!” And, with a dignified air, he held out his paw for them to kiss.

But the children were evidently not well practised in Court-manners. Sylvie simply stroked the great paw: Bruno hugged it: the Master of the Ceremonies looked shocked.

All this time Dog-waiters, in splendid livery, were running up with lighted candles: but, as fast as they put them upon the table, other waiters ran away with them, so that there never seemed to be one for me, though the Master kept nudging me with his elbow, and repeating “I ca’n’t let you sleep here! You’re not in bed, you know!”

I made a great effort, and just succeeded in getting out the words “I know I’m not. I’m in an arm-chair.”

“Well, forty winks will do you no harm,” the Master said, and left me. I could scarcely hear his words: and no wonder: he was leaning over the side of a ship, that was miles away from the pier on which I stood. The ship passed over the horizon, and I sank back into the arm-chair.

The next thing I remember is that it was morning: breakfast was just over: Sylvie was lifting Bruno down from a high chair, and saying to a Spaniel, who was regarding them with a most benevolent smile, “Yes, thank you, we’ve had a very nice breakfast. Haven’t we, Bruno?”

“There was too many bones in the——” Bruno began, but Sylvie frowned at him, and laid her finger on her lips, for, at this moment, the travelers were waited on by a very dignified officer, the Head-Growler, whose duty it was, first to conduct them to the King to bid him farewell, and then to escort them to the boundary of Dogland. The great Newfoundland received them most affably, but, instead of saying “good-bye,” he startled the Head-Growler into giving three savage growls, by announcing that he would escort them himself.

“It is a most unusual proceeding, your Majesty!” the Head-Growler exclaimed, almost choking with vexation at being set aside, for he had put on his best Court-suit, made entirely of cat-skins, for the occasion.

“I shall escort them myself,” his Majesty repeated, gently but firmly, laying aside the Royal robes, and changing his crown for a small coronet, “and you may stay at home.”

“I are glad!” Bruno whispered to Sylvie, when they had got well out of hearing. “He were so welly cross!” And he not only patted their Royal escort, but even hugged him round the neck in the exuberance of his delight.

His Majesty calmly wagged the Royal tail. “It’s quite a relief,” he said, “getting away from that Palace now and then! Royal Dogs have a dull life of it, I can tell you! Would you mind” (this to Sylvie, in a low voice, and looking a little shy and embarrassed) “would you mind the trouble of just throwing that stick for me to fetch?”

Sylvie was too much astonished to do anything for a moment: it sounded such a monstrous impossibility that a King should wish to run after a stick. But Bruno was equal to the occasion, and with a glad shout of “Hi then! Fetch it, good Doggie!” he hurled it over a clump of bushes. The next moment the Monarch of Dogland had bounded over the bushes, and picked up the stick, and came galloping back to the children with it in his mouth. Bruno took it from him with great decision. “Beg for it!” he insisted; and His Majesty begged. “Paw!” commanded Sylvie; and His Majesty gave his paw. In short, the solemn ceremony of escorting the travelers to the boundaries of Dogland became one long uproarious game of play!

“But business is business!” the Dog-King said at last. “And I must go back to mine. I couldn’t come any further,” he added, consulting a dog-watch, which hung on a chain round his neck, “not even if there were a Cat in sight!”

They took an affectionate farewell of His Majesty, and trudged on.

“That were a dear dog!” Bruno exclaimed. “Has we to go far, Sylvie? I’s tired!”

“Not much further, darling!” Sylvie gently replied. “Do you see that shining, just beyond those trees? I’m almost sure it’s the gate of Fairyland! I know it’s all golden—Father told me so—and so bright, so bright!” she went on dreamily.

“It dazzles!” said Bruno, shading his eyes with one little hand, while the other clung tightly to Sylvie’s hand, as if he were half-alarmed at her strange manner.

For the child moved on as if walking in her sleep, her large eyes gazing into the far distance, and her breath coming and going in quick pantings of eager delight. I knew, by some mysterious mental light, that a great change was taking place in my sweet little friend (for such I loved to think her) and that she was passing from the condition of a mere Outland Sprite into the true Fairy-nature.

Upon Bruno the change came later: but it was completed in both before they reached the golden gate, through which I knew it would be impossible for me to follow. I could but stand outside, and take a last look at the two sweet children, ere they disappeared within, and the golden gate closed with a bang.

And with such a bang! “It never will shut like any other cupboard-door,” Arthur explained. “There’s something wrong with the hinge. However, here’s the cake and wine. And you’ve had your forty winks. So you really must get off to bed, old man! You’re fit for nothing else. Witness my hand, Arthur Forester, M.D.”

By this time I was wide-awake again. “Not quite yet!” I pleaded. “Really I’m not sleepy now. And it isn’t midnight yet.”

“Well, I did want to say another word to you,” Arthur replied in a relenting tone, as he supplied me with the supper he had prescribed. “Only I thought you were too sleepy for it to-night.”

We took our midnight meal almost in silence; for an unusual nervousness seemed to have seized on my old friend.

“What kind of a night is it?” he asked, rising and undrawing the window-curtains, apparently to change the subject for a minute. I followed him to the window, and we stood together, looking out, in silence.

“When I first spoke to you about——” Arthur began, after a long and embarrassing silence, “that is, when we first talked about her—for I think it was you that introduced the subject—my own position in life forbade me to do more than worship her from a distance: and I was turning over plans for leaving this place finally, and settling somewhere out of all chance of meeting her again. That seemed to be my only chance of usefulness in life.”

“Would that have been wise?” I said. “To leave yourself no hope at all?”

“There was no hope to leave,” Arthur firmly replied, though his eyes glittered with tears as he gazed upwards into the midnight sky, from which one solitary star, the glorious ‘Vega,’ blazed out in fitful splendour through the driving clouds. “She was like that star to me—bright, beautiful, and pure, but out of reach, out of reach!”

He drew the curtains again, and we returned to our places by the fireside.

“What I wanted to tell you was this,” he resumed. “I heard this evening from my solicitor. I can’t go into the details of the business, but the upshot is that my worldly wealth is much more than I thought, and I am (or shall soon be) in a position to offer marriage, without imprudence, to any lady, even if she brought nothing. I doubt if there would be anything on her side: the Earl is poor, I believe. But I should have enough for both, even if health failed.”

“I wish you all happiness in your married life!” I cried. “Shall you speak to the Earl to-morrow?”

“Not yet awhile,” said Arthur. “He is very friendly, but I dare not think he means more than that, as yet. And as for—as for Lady Muriel, try as I may, I cannot read her feelings towards me. If there is love, she is hiding it! No, I must wait, I must wait!”

I did not like to press any further advice on my friend, whose judgment, I felt, was so much more sober and thoughtful than my own; and we parted without more words on the subject that had now absorbed his thoughts, nay, his very life.

The next morning a letter from my solicitor arrived, summoning me to town on important business.