Sylvie and Bruno by Lewis Carroll

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter I. Less Bread! More Taxes!

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter II. L’Amie Inconnue

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter III. Birthday-Presents

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter IV. A Cunning Conspiracy

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter V. A Beggar’s Palace

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VI. The Magic Locket

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VII. The Baron’s Embassy

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VIII. A Ride on A Lion

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter IX. A Jester and A Bear

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter X. The Other Professor

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XI. Peter and Paul

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XII. A Musical Gardener

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIII. A Visit to Dogland

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIV. Fairy-Sylvie

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XV. Bruno’s Revenge

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVI. A Changed Crocodile

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVII. The Three Badgers

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XVIII. Queer Street, Number Forty

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XIX. How to Make A Phlizz

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XX. Light Come, Light Go

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXI. Through the Ivory Door

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXII. Crossing the Line

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXIII. An Outlandish Watch

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXIV. The Frogs’ Birthday-Treat

Sylvie and Bruno Chapter XXV. Looking Eastward

Lewis Carroll – Sylvie and Bruno Chapter VIII. A Ride on A Lion

The next day glided away, pleasantly enough, partly in settling myself in my new quarters, and partly in strolling round the neighbourhood, under Arthur’s guidance, and trying to form a general idea of Elveston and its inhabitants. When five o’clock arrived, Arthur proposed—without any embarrassment this time—to take me with him up to ‘the Hall,’ in order that I might make acquaintance with the Earl of Ainslie, who had taken it for the season, and renew acquaintance with his daughter Lady Muriel.

My first impressions of the gentle, dignified, and yet genial old man were entirely favourable: and the real satisfaction that showed itself on his daughter’s face, as she met me with the words “this is indeed an unlooked-for pleasure!”, was very soothing for whatever remains of personal vanity the failures and disappointments of many long years, and much buffeting with a rough world, had left in me.

Yet I noted, and was glad to note, evidence of a far deeper feeling than mere friendly regard, in her meeting with Arthur—though this was, as I gathered, an almost daily occurrence—and the conversation between them, in which the Earl and I were only occasional sharers, had an ease and a spontaneity rarely met with except between very old friends: and, as I knew that they had not known each other for a longer period than the summer which was now rounding into autumn, I felt certain that ‘Love,’ and Love alone, could explain the phenomenon.

“How convenient it would be,” Lady Muriel laughingly remarked, à propos of my having insisted on saving her the trouble of carrying a cup of tea across the room to the Earl, “if cups of tea had no weight at all! Then perhaps ladies would sometimes be permitted to carry them for short distances!”

“One can easily imagine a situation,” said Arthur, “where things would necessarily have no weight, relatively to each other, though each would have its usual weight, looked at by itself.”

“Some desperate paradox!” said the Earl. “Tell us how it could be. We shall never guess it.”

“Well, suppose this house, just as it is, placed a few billion miles above a planet, and with nothing else near enough to disturb it: of course it falls to the planet?”

The Earl nodded. “Of course—though it might take some centuries to do it.”

“And is five-o’clock-tea to be going on all the while?” said Lady Muriel.

“That, and other things,” said Arthur. “The inhabitants would live their lives, grow up and die, and still the house would be falling, falling, falling! But now as to the relative weight of things. Nothing can be heavy, you know, except by trying to fall, and being prevented from doing so. You all grant that?”

We all granted that.

“Well, now, if I take this book, and hold it out at arms length, of course I feel its weight. It is trying to fall, and I prevent it. And, if I let go, it falls to the floor. But, if we were all falling together, it couldn’t be trying to fall any quicker, you know: for, if I let go, what more could it do than fall? And, as my hand would be falling too—at the same rate—it would never leave it, for that would be to get ahead of it in the race. And it could never overtake the falling floor!”

“I see it clearly,” said Lady Muriel. “But it makes one dizzy to think of such things! How can you make us do it?”

“There is a more curious idea yet,” I ventured to say. “Suppose a cord fastened to the house, from below, and pulled down by some one on the planet. Then of course the house goes faster than its natural rate of falling: but the furniture—with our noble selves—would go on falling at their old pace, and would therefore be left behind.”

“Practically, we should rise to the ceiling,” said the Earl. “The inevitable result of which would be concussion of brain.”

“To avoid that,” said Arthur, “let us have the furniture fixed to the floor, and ourselves tied down to the furniture. Then the five-o’clock-tea could go on in peace.”

“With one little drawback!” Lady Muriel gaily interrupted. “We should take the cups down with us: but what about the tea?”

“I had forgotten the tea,” Arthur confessed. “That, no doubt, would rise to the ceiling—unless you chose to drink it on the way!”

“Which, I think, is quite nonsense enough for one while!” said the Earl. “What news does this gentleman bring us from the great world of London?”

This drew me into the conversation, which now took a more conventional tone. After a while, Arthur gave the signal for our departure, and in the cool of the evening we strolled down to the beach, enjoying the silence, broken only by the murmur of the sea and the far-away music of some fishermen’s song, almost as much as our late pleasant talk.

We sat down among the rocks, by a little pool, so rich in animal, vegetable, and zoöphytic—or whatever is the right word—life, that I became entranced in the study of it, and, when Arthur proposed returning to our lodgings, I begged to be left there for a while, to watch and muse alone.

The fishermen’s song grew ever nearer and clearer, as their boat stood in for the beach; and I would have gone down to see them land their cargo of fish, had not the microcosm at my feet stirred my curiosity yet more keenly.

One ancient crab, that was for ever shuffling frantically from side to side of the pool, had particularly fascinated me: there was a vacancy in its stare, and an aimless violence in its behaviour, that irresistibly recalled the Gardener who had befriended Sylvie and Bruno: and, as I gazed, I caught the concluding notes of the tune of his crazy song.

The silence that followed was broken by the sweet voice of Sylvie. “Would you please let us out into the road?”

“What! After that old beggar again?” the Gardener yelled, and began singing:—

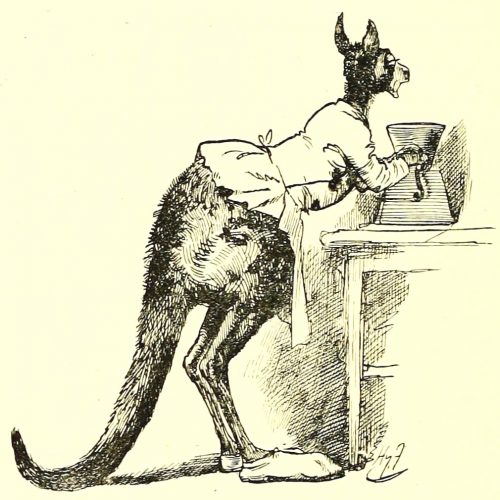

“He thought he saw a Kangaroo

That worked a coffee-mill:

He looked again, and found it was

A Vegetable-Pill.

‘Were I to swallow this,’ he said,

‘I should be very ill!'”

“We don’t want him to swallow anything,” Sylvie explained. “He’s not hungry. But we want to see him. So will you please——”

“Certainly!” the Gardener promptly replied. “I always please. Never displeases nobody. There you are!” And he flung the door open, and let us out upon the dusty high-road.

We soon found our way to the bush, which had so mysteriously sunk into the ground: and here Sylvie drew the Magic Locket from its hiding-place, turned it over with a thoughtful air, and at last appealed to Bruno in a rather helpless way. “What was it we had to do with it, Bruno? It’s all gone out of my head!”

“Kiss it!” was Bruno’s invariable recipe in cases of doubt and difficulty. Sylvie kissed it, but no result followed.

“Rub it the wrong way,” was Bruno’s next suggestion.

“Which is the wrong way?” Sylvie most reasonably enquired. The obvious plan was to try both ways.

Rubbing from left to right had no visible effect whatever.

From right to left—”Oh, stop, Sylvie!” Bruno cried in sudden alarm. “Whatever is going to happen?”

For a number of trees, on the neighbouring hillside, were moving slowly upwards, in solemn procession: while a mild little brook, that had been rippling at our feet a moment before, began to swell, and foam, and hiss, and bubble, in a truly alarming fashion.

“Rub it some other way!” cried Bruno. “Try up-and-down! Quick!”

It was a happy thought. Up-and-down did it: and the landscape, which had been showing signs of mental aberration in various directions, returned to its normal condition of sobriety—with the exception of a small yellowish-brown mouse, which continued to run wildly up and down the road, lashing its tail like a little lion.

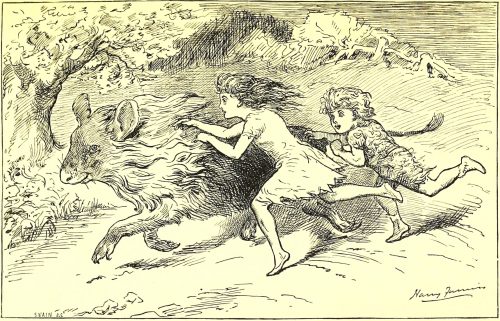

“Let’s follow it,” said Sylvie: and this also turned out a happy thought. The mouse at once settled down into a business-like jog-trot, with which we could easily keep pace. The only phenomenon, that gave me any uneasiness, was the rapid increase in the size of the little creature we were following, which became every moment more and more like a real lion.

Soon the transformation was complete: and a noble lion stood patiently waiting for us to come up with it. No thought of fear seemed to occur to the children, who patted and stroked it as if it had been a Shetland-pony.

“Help me up!” cried Bruno. And in another moment Sylvie had lifted him upon the broad back of the gentle beast, and seated herself behind him, pillion-fashion. Bruno took a good handful of mane in each hand, and made believe to guide this new kind of steed. “Gee-up!” seemed quite sufficient by way of verbal direction: the lion at once broke into an easy canter, and we soon found ourselves in the depths of the forest. I say ‘we,’ for I am certain that I accompanied them—though how I managed to keep up with a cantering lion I am wholly unable to explain. But I was certainly one of the party when we came upon an old beggar-man cutting sticks, at whose feet the lion made a profound obeisance, Sylvie and Bruno at the same moment dismounting, and leaping into the arms of their father.

“From bad to worse!” the old man said to himself, dreamily, when the children had finished their rather confused account of the Ambassador’s visit, gathered no doubt from general report, as they had not seen him themselves. “From bad to worse! That is their destiny. I see it, but I cannot alter it. The selfishness of a mean and crafty man—the selfishness of an ambitious and silly woman—the selfishness of a spiteful and loveless child—all tend one way, from bad to worse! And you, my darlings, must suffer it awhile, I fear. Yet, when things are at their worst, you can come to me. I can do but little as yet——”

Gathering up a handful of dust and scattering it in the air, he slowly and solemnly pronounced some words that sounded like a charm, the children looking on in awe-struck silence:—

“Let craft, ambition, spite,

Be quenched in Reason’s night,

Till weakness turn to might,

Till what is dark be light,

Till what is wrong be right!”

The cloud of dust spread itself out through the air, as if it were alive, forming curious shapes that were for ever changing into others.

“It makes letters! It makes words!” Bruno whispered, as he clung, half-frightened, to Sylvie. “Only I ca’n’t make them out! Read them, Sylvie!”

“I’ll try,” Sylvie gravely replied. “Wait a minute—if only I could see that word——”

“I should be very ill!” a discordant voice yelled in our ears.

“‘Were I to swallow this,’ he said,

‘I should be very ill!'”